All papers examples

All papers examples

Disciplines

- MLA

- APA

- Master's

- Undergraduate

- High School

- PhD

- Harvard

- Biology

- Art

- Drama

- Movies

- Theatre

- Painting

- Music

- Architecture

- Dance

- Design

- History

- American History

- Asian History

- Literature

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- English

- Linguistics

- Law

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Ethics

- Philosophy

- Religion

- Theology

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Economics

- Tourism

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- Psychology

- Sociology

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Anatomy

- Zoology

- Ecology

- Chemistry

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Geography

- Geology

- Astronomy

- Physics

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- Internet

- IT Management

- Web Design

- Mathematics

- Business

- Accounting

- Finance

- Investments

- Logistics

- Trade

- Management

- Marketing

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Technology

- Aeronautics

- Aviation

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Healthcare

- Nursing

- Nutrition

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Journalism

- Public Relations

- Education

- Educational Theories

- Pedagogy

- Teacher's Career

- Statistics

- Chicago/Turabian

- Nature

- Company Analysis

- Sport

- Paintings

- E-commerce

- Holocaust

- Education Theories

- Fashion

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Science

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

Paper Types

- Movie Review

- Essay

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Assessment

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Case Study

- Coursework

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Assessment

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Case Study

- Coursework

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- Essay

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Interview

- Lab Report

- Literature Review

- Marketing Plan

- Math Problem

- Movie Analysis

- Movie Review

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Online Quiz

- Outline

- Personal Statement

- Poem

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Quiz

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- Resume

- Speech

- Statistics problem

- SWOT analysis

- Term Paper

- Thesis Paper

- Accounting

- Advertising

- Aeronautics

- African-American Studies

- Agricultural Studies

- Agriculture

- Alternative Medicine

- American History

- American Literature

- Anatomy

- Anthropology

- Antique Literature

- APA

- Archaeology

- Architecture

- Art

- Asian History

- Asian Literature

- Astronomy

- Aviation

- Biology

- Business

- Canadian Studies

- Chemistry

- Chicago/Turabian

- Classic English Literature

- Communication Strategies

- Communications and Media

- Company Analysis

- Computer Science

- Creative Writing

- Criminal Justice

- Dance

- Design

- Drama

- E-commerce

- Earth science

- East European Studies

- Ecology

- Economics

- Education

- Education Theories

- Educational Theories

- Engineering

- Engineering and Technology

- English

- Ethics

- Family and Consumer Science

- Fashion

- Finance

- Food Safety

- Geography

- Geology

- Harvard

- Healthcare

- High School

- History

- Holocaust

- Internet

- Investments

- IT Management

- Journalism

- Latin-American Studies

- Law

- Legal Issues

- Linguistics

- Literature

- Logistics

- Management

- Marketing

- Master's

- Mathematics

- Medicine and Health

- MLA

- Movies

- Music

- Native-American Studies

- Natural Sciences

- Nature

- Nursing

- Nutrition

- Painting

- Paintings

- Pedagogy

- Pharmacology

- PhD

- Philosophy

- Physics

- Political Science

- Psychology

- Public Relations

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Religion

- Science

- Shakespeare

- Social Issues

- Social Work

- Sociology

- Sport

- Statistics

- Teacher's Career

- Technology

- Theatre

- Theology

- Tourism

- Trade

- Undergraduate

- Web Design

- West European Studies

- Women and Gender Studies

- World Affairs

- World Literature

- Zoology

Afterlife for the Living, Coursework Example

Hire a Writer for Custom Coursework

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Ancient Greeks and Early Christians

Before any comparison and/or contrast of ancient theologies can be made, it must be noted that many share similar characteristics, and especially in regard to beliefs about life after death. The reality is that, as polytheistic cultures were evolving and monotheism was taking root in societies, the two borrowed basic concepts from one another, and there is a great deal of polytheistic thinking in the earliest forms of today’s major religions. For example, while it seems strange from a distance of thousands of years, Early Christian and ancient Greek ideas of what happened at death were remarkably similar (Endsjo 2). In art and literature, both forms of worship emphatically stressed that the destruction of the body – usually in gruesome warfare – was the end of mortal existence. That many of these depictions are so violent seems to reinforce the shared belief that life as man knows it is absolutely finite. The differences between the two faith lies most strikingly in how each perceived the next phases. For the Greeks, the body could never be reclaimed, and the remaining soul took on whatever form Hades, or the underworld, demanded of it. For the Early Christians, the body would come back when Christ returned and the resurrection occurred (Endsjo 121). The major differences aside, and most notably the Christian dismissal of “pagan” gods notwithstanding, the two faiths nonetheless shared a belief that man was destined to die and move into another realm of existence. For the Greeks, this translated to an eternal state of being only the soul, or essence; for the Early Christians, the soul was as much a temporary state of being as the physical body, which would be given again.

Another parallel between Greek and Early Christian worships in regard to life after death may be seen in the actual activity believed to occur. More exactly, just as the Greeks created a complex mythology to document the affairs and populations of the dead, so too did the Christians seem to believe in an actual relationship between life and death. This may be noted in Early Christian emphasis on the roles of the saints, who died in God’s service and were honored in the afterlife for it. Living men and women in Early Christianity, much as is done today, sought to make personal connections with certain saints, in attempts to establish favor for when the day of judgment came (Mackie 135). Early Christians, through devout prayer to saints, essentially created bonds between themselves and those already occupying honored spaces in the afterlife.

The Christians desired a place granted to them by God the Father, yet they also perceived something of a hierarchy in the structure of the afterlife, one in which ordinary mortals, placed in heaven, could reside in spiritual peace until the resurrection.

Something of the same kind of “interaction” between life and the afterlife is evident in the earlier Greek worship, but in a far more defined and pronounced way. With the Greeks, as with many polytheistic cultures, the afterlife is a very complicated scenario. It may be that the same pursuit of artistry the Greeks demonstrated in their society were were just as focused on creating a strange and almost beautiful concept of life after death. Then, Greek culture had long centuries in which to add to its vision of life after death. The results were incredibly intricate, and bridge gaps between life and death as almost routine matters. Early Christians had defined characters as saints, as well as the chief figures of the Bible, to populate their afterlife, but the faith still maintained more of a distance, or reverence, between the realms. Even if a mortal could work toward acceptance into God’s favor, what actually occurred after was indistinct. For the Greeks, there were, literally, maps, as well as rules and regulations as complicated as any in life. On one level, the Greek conception of the realm of the dead did not always place it beneath the Earth’s surface, as the Christian hell was conceived; Hades’ domain was depicted in The Odyssey as across the ocean. The same kind of location is referred to in Euripides’s Medea: “The shores where Death doth wait” (70). Then, even when Hades became established as the Greek “underworld,” at least four rivers besides Styx gave access to it (Ogden 92).

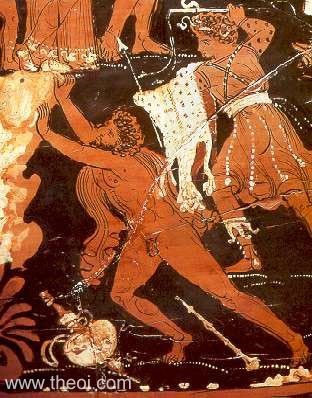

More than any other difference, Greek views of the afterlife insist on relationships between the living and the dead in a way Early Christianity could not. For example, in Homer’s Odyssey, the witch Circe tells Odysseus that only in venturing into the underworld can he hope to learn his future. Moreover, she directs him to the dead prophet, Teiresias, who remains the greatest seer of all (Homer 32). This indicates clearly that death by no means translated to an end to usefulness for the living; it was, as in this case, simply a powerful obstacle to be overcome. Myth after myth in ancient Greek lore documents similar interactions. The most celebrated may be the abduction of Persephone, daughter of the goddess Ceres, by Hades himself. He desires a bride and captures here but, owing to the desolation on Earth caused by Ceres’ grief, the gods decree a compromise. Persephone rules as queen of the underworld for six months, and lives with her mother the rest of the year. Similarly, Greek concepts of life after death seem to have been based on knowledge of human affairs, certainly in terms of specific punishment. In the myth of Sisyophos, for example, the king of that name is condemned to spend eternity pushing a boulder up a mountain, only to see it fall each time he nearly succeeds. This is a distinctly human type of punishment, or at least one presented in terms understandable to any human, and it is removed from the less defined ideas of what hell itself means in Early Christian worship. That hell most certainly equates to pain and suffering, but it is not expressed in so “ordinary” a form. Consequently, while both Greek and Early Christian religions viewed the afterlife in ways relating it to actual living, the Greeks insisted on degrees of humanity and interaction with life not evident with the Christians.

The Return of Persephone

Lord Frederick Leighton, c. 1891

In the above painting, the legend of Persephone is romanticized vividly as a mother recovers her desperate daughter from the underworld.

The Punishment of Sisyphos

One image on vase, artist unknown. c. 330-310 B.C.E.

In the above, the eternal agony of Sisyphos is seen as a Fury whips him to push the boulder up the hill.

Works Cited

Endsjo, D. O. Greek Resurrection Beliefs and the Success of Christianity. New York: Macmillan, 2009. Print.

Euripides. Medea. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986. Print.

Homer. The Odyssey. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. Print.

Mackie, G. V. Early Christian Chapels in the West: Decoration, Function, and Patronage. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003. Print.

Ogden, D. A Companion to Greek Religion. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2010. Print.

Photograph Websites

World Classic Gallery. The Return of Persephone. http://www.allartclassic.com/pictures_zoom.php?p_number=81&p=&number=FLL019

Theoi Greek Mythology. The Punishment of Sisyphos. http://www.theoi.com/Gallery/T40.5.html

Stuck with your Coursework?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Tags:

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

writing help!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee