Organization Change by Promoting Employees’ Growth, Dissertation Example

Abstract

Breadth

The Breadth component of this KAM outlines principles of organizational theory, with emphasis on the overall aspects of the different organizational models. This section compares Hiatt’s employee based, ADKAR, Kotter’s (2002) transformational thought, Bertalanffy’s (1968) systems theory, and Burke’s (2007) transformation leadership models. The analysis explains several internal and external organizational factors that can influence human behavior and ultimately facilitate or prevent sustainable growth.

Depth

The Depth section outlines representative organization theories from a range of possibilities, with focus on theoretical models with the best application toward behavioral motivators as change management strategy. The study looks to Warner Burke’s (2007) transformation leadership change model as the preferential perspective and employs the model to test the viability and effects of leadership as solution. It also calibrates data and the results from replicable studies; gauging capacity in oversight of employees, and successful mitigation their resistance to organizational change and finally help to establish effective transitions. The KAM evaluates strategies suggested by current research as valuable mechanisms in terms of how organization change can occur and results in 25 and 30 pages of discussion on individual change patterns focused primarily on factors influencing individual behavior. This analysis will bring to light evidence of the organizational change theorists in the Breadth. It will look at the practical application of their writing, particularly in the area of individual attitude and values that can lead to organizational change. The Depth Demonstration will also include an Annotated Bibliography of not less than 15 peer-reviewed articles published within the last five years.

Application

The Application component discusses the strategy that has to be adopted by an organization to effectively manage organization change and development. This segment formulates the steps that are needed organizations as they build categorical leadership capabilities into an overall strategy for success in the change management process and sustainable growth. The overview of the work looks at the theoretical prospectus’ currently impacting organization research, and centralizes the efficacy of leadership as an integrated behavioral and operational change management strategy; intended to inform application of leadership methodologies in a real setting. The Application component consists of a PowerPoint presentation based on information drawn Breadth and Depth sections in the KAM, and provides recommendation to development of professional employee training systems.

Breadth

AMDS 8612 Model of Organizational Change and Development

Organizational Change and Development describes the study for the AMDS core knowledge area on organizations and human behavior. The foregoing analysis explains organizational theories compare them and finally choose the better defined holistic model as the preferential model that can emphatically manage the people side of change. The first part of the KAM engages in a dialogue with comparative organization theories and looks at the human factors central to change in entities as they mitigate structural transformations. The latter part of the KAM addresses application of recommended, replicable models proposed in seminal organizational leadership queries.

Breadth Demonstration

The emergence of organizational theory (OT) as a disciplinary canon of scholarly thought was largely inspired by the historical development of praxis developed out of Psychological and Sociological theories on institutions and behavior. Early twentieth century thinkers like Max Weber (1947) were seminal in their response to nineteenth century queries into Capitalism (i.e. Karl Marx), and incorporated the thought of Structural-Functionalist colleagues such as Emilé Durkheim into their philosophies on organizational formations. In the late-capitalist period, organizational models have changed to proscriptive measures toward catering to the needs of organizations, and theoretical erudition now caters to the culture of the organization and values of organizational participants as their ‘mental maps’ are examined toward solutions, rather than seen as an evidentiary end point assumption to philosophical projection.

In the face of accelerated and flexible capitalization in the era of globalization, human resources are no longer portrayed as cogs in a machine, or in Weber’s case an ‘Iron Cage,’ but highly malleable and important assets to corporations (Weber, 1920). Employees have been re-interpreted through the lens of sustainable growth as companies are forced to expand and contract at a moment notice. Training has entranced as the key mechanism for optimizing human resource assets, and even non-management employees are increasingly finding themselves as decision making ‘actors’ in horizontal and often virtual settings. Since the 1990s, Change Management theories have promoted an evolution of thought in business and professional training, and ‘the people side of change’ has been, of course, the single most tenacious and challenging factor within the change management equation. As the discipline of change management has come to accentuate distinct ‘thought worlds’ behind the operational planning strategies within organizational change, technological integration of knowledge sharing systems enhances up-to-the minute decisions making options, and leadership competencies.

Inextricably linked to larger economic and institutional processes and structures, OT theorists consider a spectrum of philosophical and scientific options to articulate application and recommendation. From a historical materialist perspective, the role of OT is largely dependent upon economic shifts as organization models are rooted in business and professional activities, and then broadly categorized into Classical and Contemporary approaches (Bateson, 1979). In short, all aspects of the organization converge in an effort to build systemic capacity, and better the entity’s chances at competition. Apprehension of the relevance of human psychology within change management studies is now critical. Employees must be proponents of the processes and systems that they work with if organizational strategies are to succeed. Prioritization of the individual as the core priority in organizational competencies has designated the human factor as the most important asset to growth in change organizations. Not surprisingly, managers are prompted to design compensatory strategies that include both material and motivational benefits to employees (Burke, 2007).

Organization Theories: A Legacy of Change

In the twentieth century, organization theories have been constituted of two major schools of thought: Classical and Neo-classical approaches to management. If the Classical approach emphasizes authoritarian principles of hierarchy and top down authority, Neo-classical theories (human relations and systems theory) emphasize things like employee welfare and organizational structure (Bateson, 1979). Foundational to both schools of thought within OT is the theoretical framework on organizations developed by Max Weber’s theory of bureaucracy. The general position of the paper asserts that temporal instantiation of organizational structure affects the outcome of theoretical application, and even limited hierarchical formation most often supports neoclassical approaches (Bateson, 1979).

In 1947, Max Weber’s classical theory on bureaucratic organization articulated the definitive role of institutions in both democratic and national socialist countries. Rejecting political distinctions as the primary basis for institutional models, Weber argued that institutions, and particularly highly bureaucratic ones, contain authority channels and control mechanisms transferrable to varied politic-economic contexts. The first thinker to parallel what becomes known later as corporate America’s ‘Yes Man’ debacle, Weber asserted that the ‘Iron Cage’ is an institutional form of power that retains its longevity beyond individual employees through systemic forces; and in spite of the fact that those employees carry the environmental psychology of those forces in their own minds (Weber, 1920). A perfect example of Weber’s structural-functional approach to the Sociology of Organizations, is later work on bureaucratic authoritarianism in South America in the 1970s and 1980s during Argentina’s dictatorship(s); whereby near fascist political governance was interfaced almost seamlessly with liberal market practices through institutional continuity with bureaucratic formations that enabled such oppression (O’Donnell, 1998). Individual psychology is noted as the reflexive mechanism that empowered those institutions in an era when people were hesitant to make changes in private businesses where there was a significant public (i.e. State) partnership or like influence.

The strength of Weber’s theory on bureaucracies is that it provided an indispensable blue print for most OT theory to the present, and is readily recognized despite orientation toward his mid-twentieth century thought, as a catalyst to discussions on the limits of professional specialization and division of labor (Laszlo, 1996). For followers of classical theory, the somewhat rigid and mechanistic structures are enhanced by knowledge of Weber’s ideas on critical examination of the state of those human resource related responses to bureaucratic problems (Laszlo, 1996). Typical of its roots in post WWII theory, when economic benefit was the single most mitigating factor to employee motivation, shortcomings to Weber’s thought denies more thorough explanation of motivational forces beyond consequence of economic reward. Ideas on systemic effectiveness, employee welfare on the job, and management decisions on division of labor are largely ignored in his work. In addition to the transformations in capital flows in the latter half of the twentieth century, the advent of labor laws in developing countries, and especially the United States in response to the civil rights, gay and lesbian, and women’s movements has given rise to much diversity in interpretation of OT theories, and substantiates the basis of the ‘individual behavior’ models in neoclassical organization theory (Laszlo, 1996).

In general, neoclassical theories are directed at improvement of Modernist, or vertical ‘authoritarian’ structures reflected in the classical theories, and as a consequence focus on human relations aspects of organizational growth as interpreted through the legal sphere in developed nations (Laszlo, 1996). Neoclassical OT has generated three (3) distinct theories: 1) Human Relations Theory; Behavioral Theory; and 3) Systems Theory. Leading objections cited against classical theories are the tendency of employees to be subject to organizational cultures saturated by devolving productivity in response to over conformity, rigidity and inefficiency. Typical of the Neo-Marxist developments ingrained within neoclassical OT thought, are the disjunctures recognized as ‘alienation’ where employee motivation is retracted by way of blocked creativity and individual appreciation of employees. To this end, the proscriptive elements of neoclassical theory are often dictated by ‘genuine concern for the human needs of workers’ (Laszlo, 1996). As Laszlo notes, the resultant sub-fields in OT theory – Human Relations and Systems Theories – only improve upon employee’ welfare in a context that parallels Weber’s Iron Cage. Indeed, the translation of Systems Theory in other fields such as international development systems theory for gauging international market impact reveals similar conjecture – humans are relative yet elsewhere. Criticism points the distinction between manipulation of working conditions and improved productivity, bet without the necessary ‘human’ transformations in the existing, and oft debilitating bureaucratic structure (Laszlo, 1996). Nevertheless, in consideration of comparison of theories applied to cases of public and private administration – and how each depended on bureaucratic structures to attain ideal results – it is clearly evident that the human relations emphasis adopted by the neoclassic theories was and still is the most efficient model for inclusion of theory in administrative praxis (Laszlo, 1996).

Experimentation with OT as a hypothesis for applied research dates back to Roethlisberger and Mayo in their classical analyses from the 1920s. Chandler (1962) undertook their popular methodology of organizational experiment and conducted a replication of the model at the Western Electric plant facility in Hawthorne, Illinois. The experiment employed manipulations of employee conditions on an industrial line. Intensity of lighting served as the testing mechanism, whilst the employees assembled electronic products. The study found out that better lighting had a very positive impact on the workers productivity. Deductively the study cites a Human Relations approach increased employee capital output, in accommodation of employees, distinct from threatening or forcing them to work according to the older models popular in the earlier part of the century. Workers not only evolve into positive, friendly and caring employees, but the accommodation to workers’ conditions had direct impact on line productivity. The results replicate Mayo’s findings, and reflect the ‘plain and intelligent action’ recommended to organizations as a result (Chandler, 1962). Chandler’s findings indicate that ‘caring’ regardless of how ephemeral in tone, can best substantiate employer-employee relations through concrete measures. Caring translates to both alternative and traditional forms of employee benefit, and we can see convergence of compensation, housing, promotion, working environment, health benefits etc. into the spectrum of institutional management practices intended to promote productive, agreeable, disciplined and result oriented worker response.

Otherwise known as the Hawthorne Experiment, Chandler argues that the instrument is in and of itself is not especially reliable in evaluation of organization management theories. As he maintains, when an organization continually implement what he calls ‘management fads’ in a bid to produce Hawthorne effects, the employees may realize the motive behind such actions. Objectivity may, then, be considered unreliable. The situation may also create a negative attitude amongst employees, as the un-consented to ‘authoritarian’ classical-type decision making is revealed ‘covert;’ hence toppling trust like a house of cards in the face of manipulation and tricks (Chandler,1962). In its place, modern scholars concur that cohesive environments based on mutual compact must be based on ethical institutionalized protocols, and attendant, agreed upon benefits to employees stipulated in policies shared across the board. In cases where the structure reflects strict, vertical hierarchies like those studied by Weber in calculation of the social cost of bureaucracies, policy frameworks should still motivate employees to produce, grow and actualize themselves as professionals, and in so doing improve productivity.

Basis of Comparison of Organizational models

Neo Classical Models focus on managing particular aspects of change, and systematic implementation of the models requires clarification of certain important questions:

- Why of change? – forces and sources

- What of change? – order, scale, degree

- How of change? – adaptive, reactive, active, or planned

- Target of change? – outcome

Upon evaluation of the systemic classification of change as an organizational matrix of responsibilities, application of neoclassical theories to management assessment of particular challenges requires researched knowledge of recommended models for best practices within organization.

The selection of a preferential model is not an arbitrary choice, but predicated upon instrumental deployment toward adequate outcomes, and dissemination of data analysis. Assumptions are taken into account when applying theoretical hypotheses to those situations, as unexpected human inputs into a situation may compound testing of those theories, and assumptions further those complications. In short, tests must be objective in foresight, and grounded in application over the course of time, as controlled experimentation is fairly difficult in an environment where natural business transactions and interpersonal communications are taking place. Additional interference by systemic forces both internally and externally, such as logistics matters, might pose serious errors in data collection, and in clear cut articulation of findings.

Assumptions are present inherently in theory, and layers of assumptions stemming from application of secondary sources to primary research, even in replicable studies, can cause problems in calculation of solutions due to variance in context. Kezar (2001) offers a model of classificatory determination of six (6) main categorical elements of analysis for developing insights into organizational change processes: 1) Evolutionary – event sequence; 2) Teleological – rational goal setting; 3) Life cycle – start-up to regulation; 4) Dialectical – conflict negotiation; 5) Social cognition – observational; 6) Cultural – unit and mode of change.

Leaders employ this organizational assessment model toward decision making in theoretical application of appropriate methodologies toward the most efficient and effective change management strategies based on a variety of internal and external environmental factors: 1) Organizational context; 2) Factor necessitating change; 3) Strategy for change; 4) Actors’ involvement; and 5) Change management practices.

Application of Organization Theories

Change management decision making is based on both internal and external categories of analysis. As mentioned, theorists apply various Organization Change Management models as formulas for interpreting and planning strategies of effective leadership. The forthcoming segment reflects on the KAM’s four change management models to understand and comprehensively address the strengths and weakness of each of these models. Indeed, much of what is interpreted through the behavior based change management models can be integrated into organizational analyses like PESTLE (Political, Economic, Sociological, Technological, Legal, and Environmental) and SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analyses which are utilized broadly by organizations toward fiscal and operational sustainable growth. The PESTLE and SWOT analyses offer post experimental application of the individual behavioral hypotheses, and a visual of the overarching goals and responsibilities involved in actual change management as IT systemization of much of administrative, financial, inventory and market tracking, and operational logistics are put into rapid knowledge share databases for immediate reporting and further change management planning.

The remainder of this KAM looks at four central OT models: 1) ADKAR Model; 2) Transformation Model; 3) Systems Approach Model; 4) and the Transformation Leadership Model. Each model offers a ‘secret mantra’ for promoting successful leadership in the context of change. All four of the studied models are ‘people-centric’ as they point as they focus solutions on constructive bridge building amidst individual reactions to change efforts (Adhikari, 2007). In industry terms the models are equipped to combat the effects of organizational change with savvy management strategies defined as a set of processes, tools and techniques designed for leadership. Change management is not only a process by which organizations ‘think,’ they serve as a benchmark for individual professional growth, as the organization transitions from a former arrangement to a desired future state. People focused strategies enable organizations to achieve the specific objectives in identified change through individual and collective acknowledgement, contribution and training. At each stage, the four theoretical positions discussed in the KAM look at how individuals and groups merge to support and participate in change, so that what is embraced as culture and/or protocol, works systemically toward the objectives and the future sustainability of that organization in perpetuity (Hiatt, 2006).

ADKAR Model

ADKAR (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Acknowledgement, and Reinforcement) offers real time application of a goal oriented model of change management (Prosci, 2000). Formulated in response to a research study with 300 companies all n the nascent stage of ongoing, multiple change projects, reactions and experiences from these projects were recorded, and developed into a standard for interpreting real time calibrations and measurements of iterative employer- employee communications strategies with recommended solutions that enhance all participatory members.

Interested in derivation of depth insights only available through communicative praxis, the model is not so much a consensus building strategy, as it is a grounded theoretical methodology for creating dialogue and employee-centric solutions. An instrument and an instructional reporting tool, the model ‘trains the trainer’ as employees work through policies to mitigate actual and potential challenges and tensions arising out change initiatives. Streamlined in approach, the ADKAR Model interfaces organizational assets through consideration of the two primary dimensions where value added decisions may be employed and defined: 1. Business dimension of change; and the (b) People dimension of change:

- Business Dimension of Change:

Involves the same standard practises that help in the business domain of organizational change; like the need to establish business opportunity; define scope and objectives of projects; and formulate new systems and organizational structure for the organization.

- People Dimension of change:

The model was initially used to determine whether the change management activities like proper training and communication sessions were working – whether there were signs of transition. The model had its root in traditional change management theories to a given goal.

In a study conducted in 248 companies, the following observations were made: an effective change in management policies related to the employees had been listed as one among the top three predominant success factors of organizations. Moreover, guiding and mentoring managers; making them aware of strategies and development goals of the organization; and keeping them in sync with the employee welfare opportunities were considered to be the critical factors for sustenance and development (Prosci, 2000). Prioritization of employee success turned out to be the crucial factor in the organizational change prospectus. For instance, in situations where organizations invest research and development time and financial costs correlated to implementation of new software for total organizational IT integrated operating networks, management has much at stake in terms of planning. At every stage in the development of such a model, the human factor must be addressed, as employees must be able to use and optimize performance in the organization. Immediate counters in such planning strategies typically include questions such as: Was it necessary? How will it help? Isn’t it is a waste of time? Why we were not informed about the change earlier, or will we be trained? Effective management of the change in relation to the human dimension requires is fulfilled by five (5) key points that are the basis of the ADKAR model (Table 4):

Table 1

| A | Awareness (clear information about conditions and policies in a business is a core goal of early communications to the process of change ) |

| D | Desire (to be a part of the change or the goal ) |

| K | Knowledge (of how to change to attain the goal of change) |

| A | Ability (to be capable enough to implement and resistance management and sponsorship for work ) |

| R | Reinforcement (vigilance to see that the goal of change is taking place in order) |

Table 1: ADKAR Model

Trends in OT case studies reflect the state that employees are most often in at time of change management planning (i.e. concerned, stressed and not informed). In such a case, ADKAR suggests that if: employees are properly informed; made aware of the advantages of new software; communicated to about working knowledge of software; and trained to match their ability in accordance to the program and encouraged to implement and sustain the change; then ADKAR ensures to attain effective positive organization change. The ADKAR model focus on employees postulates the real cause of failure in change management processes is best negotiated by way of competent assessment and planning frameworks, and implemented formulations that encourage employee involvement, motivation, and commitment in core competency design. The results from the ADKAR Model are easily measured and evaluated according to task specific classification. It can be difficult for the larger companies to adapt this model due to sample size, time and resource constraints. Categorical determination of best practices implementation of ADKAR is seen in the following organizations: 1) Pluralistic Social Construct; 2) Oriented Social Construct; 3) Developing Social Construct.

Although the ADKAR Model’s strategy for change is impacted by the demand of the external environment and the competition from market, the application of the diagnostic approach is highly personalized in tone: 1) Diagnose employee resistance; 2) Assist employee in transition; 3) Create change strategies for professional and personal development; and 4) Design and execute change management for human resource benefit.

Consideration of actor involvement in the methodological approach is varied, as change can be implemented by different levels in the organization. The actor involvement is largely dependent on the level and nature of the change process. So the actors can range from the top level executives to supervisors in the organization.

Systems Approach Model

The Systems Approach model in its crudest form was first proposed by biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy as ‘General Systems Theory’. Bertalanffy amalgamated the analytic and the synthetic methods of analysis in order to capture both reductionism and holism in matrices of systemic relationship. Critical to his model, is the consideration of an ‘open ended’ system in the face of traditional physics formulas that consider that all systems are closed. According to Bertalanffy (1969), organisms constantly needed an inflow and outflow with their environment to maintain open systems. The interaction is two sided; input that enters from outside and output that exits from the system. “A system may be defined as a set of elements standing in the interrelation among them and with [the] environment” (Bertalanffy, 1968). Revolutionary in concept, his work has inserted a process oriented model of open ended systems where functional structuralism once thrived in a variety of theoretical fields. Candid in his retort of traditional physics he disagreed to the fact that the organisms do not intervene or interact with the external world.

Timely in approach, the Systems Theory model sought to transition from orthodox methodologies to conceptual formulations offering almost infinite opportunities for change. His work emerged in moment which systemic approaches to social problems fulfilled burdgeoning Neo-Marxist interests in scholarship, where large interconnected, yet unwieldy forces such as the global economy were put into analysis as a method of locating power. Dynamic in nature, the concept of the open ended system offers a model of flexible and stable expositions that are mature enough to interrelate, integrate and oscillate parallel to opposite forces.

Bertalanffy’s model thus formulated concepts like wholeness, organization, teleology and differentiation which were not prevalent in the conventional models. It is capable of giving exact definitions of organizations and helps prepare the quantitative analysis of the organizations. He observed that society is plagued with ethological, ecological and ethical issues in respect to human affairs. Social problems literature feeds into this discussion, and comparative economics posited an aggregate method of deploying Bertalanffy’s ideas as development theory vested economists attempted to discern the impact of groups of individuals were only concerned to amass large profits for a minority group neglecting the basic needs of other people. The model tries to adapt to the welfare of humans in a global system, in its own environment. This led to the system thinking. Those major concerns for Bertalanffy were the source of introduction of idealism in his proactive attempt at systemic design toward protection of the interests of future generations. Advocacy of such a model with its priority in global morality set the pace for a ‘universal’ framework for thinking about economies of scale, where focus on individual values alone is virtually impossible. This Systems Theory model for change management is best adapted in static organizations. The actors involved are mostly from the top management. However, in sub-system levels there is interdependence in interactive levels with the support of the top management. Here the organizations consider businesses to be a system, which regulates the inputs to deliver outputs to ‘Oriented Social Constructs.’ Factors necessitating change in the approach include: 1) Effect of external environment; 2) Substantial interdependence between sub-systems; and 3) Inputs to the system. Here the agent of change studies the system; acts in sync to alter the state of the system; and once the change is delivered the equilibrium is established.

Transformation Leadership Model

Hacker Model

The term ‘Transformational Leadership’ was first introduced in the book by J.V. Downton (1973) in Rebel Leadership: commitment and Charisma in a Revolutionary. In consideration of organizational leadership and human resource management practices, the essay imports a rather old, yet ‘universal’ paradigm from Psychology, Maslow’s ‘Hierarchy of Needs;’ premise to fulfillment of the state of human nature as a means to consensus building and the inculcation of ‘desire’ in work. In 1943, Abraham Maslow introduced his work in Psychology, A Theory of Human Motivation. Throughout the analysis of troubled organizations, we can see the development of a series of communications and management issues which ultimately lead to strategic management oversight problems, and ultimately competitive performance of the entity.

At each stage of the employment relationship, employees might react to negative influences resultant from incompetently managed organizations.

In the context of globalization, entities seeking to grow rapidly have often confronted this issue, due to unrealistic expectations of a global corporation in various cultural and national contexts where factors such as accounting practices, language, regional management styles and laws all impact the employer—employee relationship.. As psychological barriers impinge upon application of a synthetic organizational culture, case-by-case consideration of employees needs, and prioritization of those requirements within a particular setting are have revealed the almost universal application of Maslow’s projections: human capital or equitable worth as it was recognized deeply influences the financial and operational picture of an organization if misperceptions are allowed to persist in response to failures by the leadership.

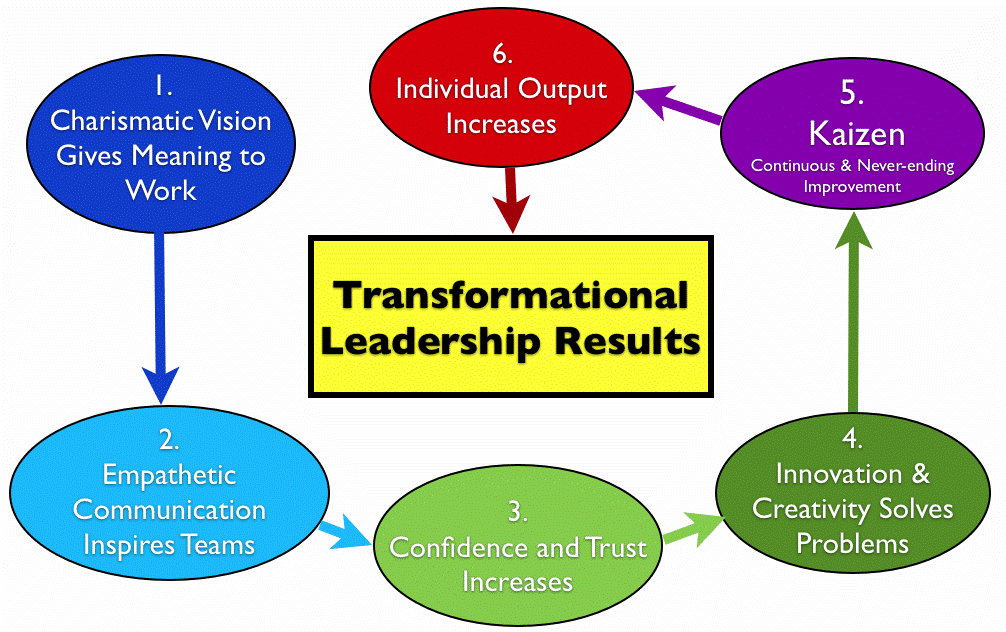

Burns (1978) first introduced the concept of transformational leadership. During his study of political leadership he identified the transformational leader, which was later used in organizational psychology as well. Burns was influenced by Maslow’s Theory of Human Needs. According to Burns, the extent to which their needs are fulfilled determines their performance level in the workplace. Essentially the leader performs the task of raising the conscience of the work force keeping in mind the diverse need of his employees. Contemporary scholars offer perspective to the theory, and articulate the leadership vision through a an ordering of intrinsic need(s) in individuals whereby, transformation leadership meets those demands, through “comprehensive and integrated leadership capacities required of individuals, groups, or organizations to produce transformation as evidenced by step-functional improvement” (Hacker, 2003, p. 3).

This model lends itself to what managers are calling ‘Organizations of Meaning’ or environments where staff is inculcated with an informational knowledge base that produces team loyalty and binds business operations with a strong sense of commitment to achieve breakthrough outcomes. A semiotics of ‘doing business’ from a cultural perspective, organizational meaning obviously translates to the external environment, and especially in transactional relationships with suppliers and customers as consumption of brand identity is simultaneous to the overall operational and market strategies forged through those ideological tenets. Organizational meaning fosters communicative consensus and encourages belief in a company’s culture of value as it is understood in daily work, and in sustainable goals. Leaders and managers transpire to forge such a culture so that employees are dedicated and precise in their decisions and contributory responsibilities according to organizational fit. When relationships are ‘mature’ as they say in industry, employees will work with a sense of accountability to the overall success of the organization. Even if ‘meaning’ is seemingly transparent, the approach to assessment of the business environment, and especially employee loyalty and competency in systems management, results are attained not through coercive or manipulative management methods; but as a natural instinctive, expression of commitment.

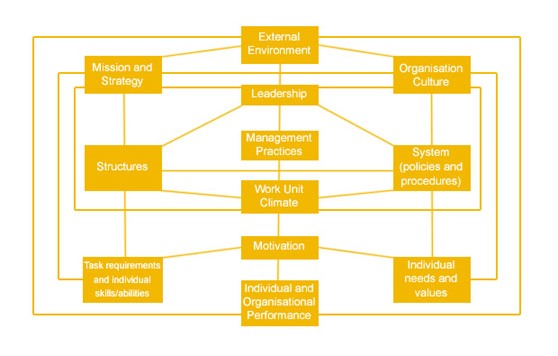

What style of Leadership is necessary to spearhead change management processes if ‘meaning’ is the coherent force behind organizational planning strategy? Organizations of distinction, such as vineyards, call for a style of leadership that appreciates and honors brand uniqueness representative of the product, the company and the consumers whom associate with that identity. Hence, meaning is not only internal in definition, but necessarily iterative in dialogue with market forces, and including competitors whom craft proximate solutions in symbolic iconography and semiotic discourse. Interestingly, at the centre of transformational leadership model is consciousness of Self. A visual representation of the model replicates a Mandala or cosmological order of the solar system by which the self of the leader provides the pivotal access by which consciousness in others is raised. Figure 5 also shows the cornerstones that underlie organizational transformations (Hacker, 2003).

Figure 1

Figure 1: Transformation Leadership Model from Hacker

Burke Model of Transformational Change

Thinking through existing theories for organizations, Burke (2007) constructed a new organizational theory that reflects actual praxis in global corporations conducting business in the ‘new market economies’ in conjunction ideas stemming from Systems Theory open systems, and meaning influenced partnership models. His model of choice was first developed by George Litwin which he later replicated in observational experimentation. Burke argues that both individuals and the contextual (organizational and societal) influence change – a mutually dependent relationship that serves to sharpen the systems processes instigated by and organizations and employee response to those changes.

Litwin conducted research on Organizational climate (Litwin & Stringer 1968), which became the framework of the Burke-Litwin model in 1992. Litwin wanted to demonstrate change management theory from the standpoint of leadership. He hypothesized that different style of leadership could create different organizational climate (environment) that would appeal to (arouse) different motives or needs. Now initially, Litwin created three separate organizations led by distinctly different leaders, one being a power oriented leader to arouse followers need for power; a second one being the achievement- oriented leader having a strong task focus with challenging goals; and a third being an affiliation-oriented leader to arouse relationship and interdependence needs. His study showed that performance and morale differed significantly across, the three laboratory organizations; with the achievement leader having both the highest performance and the highest morale.

The new model to guided change management, while not ‘objective’ in stipulated elements, is simultaneously highly flexible in that one that does not assume a beginning, middle, and end to a change effort. Instead, change efforts are regarded as contiguous to the whole systems process. Change can emanate from any unit, function, or level within an organization. Regardless of its origin, leadership is required. There can be leaders anywhere in an organization, but if the organization change is large in scale and transformational in nature and requiring significant change in mission, strategy and culture, then leadership must come from the top of the organization; from executives and particularly the chief executive (Burke, 2007). Assessment utilizing the Burke Litwin Model approaches change management with the following assumptions: 1) Demonstrates how to create the first order and second order change; and 2) Differentiates between organizational change and organization culture. The model is comprised of essential elements defined by four (4) key terms: 1) Organizational climate; 2) Organizational culture; 3) First order changes; and 4) Second order changes. Results to the pilot study reveal: 1) Transformational change occurs in response to the external environment, which directly affects mission, leadership, culture and strategy of the organization; 2) Transactional factors are also affected; 3) Motivation follows, affecting performance; and 4) Feedback loop response enables the organization to make assessed changes in both the internal and external environment.

Table 2

| Organizational Climate | Defined as the perception and attitude of the people about the organization. These perceptions are easy to change as they are mere reactions to current organizational and managerial practices. |

| Organizational Culture | The deep rooted assumptions, beliefs and values that are often enduring, unconscious and difficult to change. Changing culture is much more difficult than hanging climate. |

| First Order Changes | Mostly labeled as transactional, evolutionary, incremental or continuous change. In first order change some features of the organizations change but the fundamental aspects remain the same. |

| Second order changes | Typically known as transformational, revolutionary, radical, incremental or discontinuous change. Here the nature of the organization is fundamentally and substantially altered i.e. the organization is transformed. |

Table 2: Burke-Litwin Transformational Change Model

A flow chart of the Burke-Litwin model below illustrated the planned change flows from top to bottom and focuses on both transformational and transactional factors of change. It focuses on two aspects of change: transformational and transactional factors. External environment, mission and strategy, leadership, organizational culture, and individual and organizational performance are considered the transformational factors. As a part of the transformational organizational change model developed for this study, additional components classified as transactional factors by Burke-Litwin relating to structure and systems have been defined as transactional in nature. In the new model, Burke restated systems and referred to it as quality techniques and tools (Burke, 2007).

Figure 2

Figure 2: Burke Litwin Causal Model of Organizational Performance and Change

In 1994, Burke developed the LAI (Leadership Assessment Inventory) based on the assumption that the best way of differential transformational and transactional leadership is to assess the manner in which the subordinates are empowered. Burke observed that transformation leadership was significantly affected by reports of subordinates. Leadership with a vision and personalized goals could bring in more effective change management as compared to charismatic leadership. Ideal Functions of a Transformation Leader according to Burke:

- Helping employees develop and maintain a collaborative culture: Leaders take initiative to help develop continuous improvement and collective responsibility to motivate people. Transformational leaders help the staff to set up collaborative goal setting, actively communicate the company’s vision, combat isolation, use bureaucratic measures to support cultural changes, share leadership by delegating power, and

- Fostering staff development:Fostering staff development among the employees is an integral part of leadership. When the leader augments and initiate steps for fostering staff development it enhances the process of professional growth. This is a process to inspire and energize the workforce.

- Helping peoplesolve problems more effectively: Transformational leader stimulates the workforce to voluntarily engage in new activities and to give that “extra effort” needed for the transformation. They use practices to help the workers work smarter and not harder. The leaders share a genuine belief that a team effort would solve problems more easily than individual effort.

The focus of the Transformational Leadership Model goes beyond mere success of the individual leader. It seeks to transform the minds, hearts and attitudes of followers – including the leader. Leaders contribute to the process by applying their leadership characteristics, such as ethics, character, beliefs, values, knowledge and skills. The power that is attributed to the leader gives a sense, and an authority to accomplish certain objectives and tasks in the organization. However, this power can only make a boss not a leader. Leadership asks for more than authority- it makes the followers achieve goals rather than just meeting their daily job requirements. The goal of the leader is to transpire passion, zeal and a vision to pursue their best efforts for the development of the organization to their individual selves. The Transformational Leadership Model meets important situations which require change management by way of ‘need for incremental improvement, crisis management, and creation of new organizational capabilities. Actors involved in this model are normatively upper management, with a downward dynamic of change, but with horizontal participation over time.

Organizations of the future will be more focused on ‘mass customization’ (as a reflex action in the face of shifting unique market demand) rather than ‘mass production’ (resource utilization in economies of scale). This necessitates tighter integration with partners in the operational logistics chain in association with vendors, and in the management chain in oversight of customer service and employee collaboration. The integrated systems approach to a synthesis of organizational leadership that can be optimized through things like technological inputs is now more important than ever, as product and service chains form knowledge in their channels, and financial investment and market strategies have high stakes in this. For human resource management leaders, flexible accumulation of capital has come to mean change management is the norm, not to the exception to everyday business responsibilities. The Model is applicable to all organizational types: 1) Oriented Social Construct; 2) Pluralistic Social Construct; 3) Developing Social Construct; and even 4) Unstable Systems, as businesses attempt to develop adequate core competencies to benchmark their goals and objectives.

Transformation Model

Transformation management models as defined by J.P. Kotter (2002), in The Heart of Change, looks at real life stories about how people have implemented change management strategies in their organizations. Illustrated through a series of practical experiences in his research on one hundred companies, Kotter looks at how consulting interfaces with transformation initiatives. He believes that the change process is time consuming, and typically has to pass through several stages in an attempt to implement a successful change effort. Mistakes made during the transitional phase in any stage of the change process may lead to long term negative results in the organization. His model is useful for public-private organizational program models, and necessarily advocates that change does not happen overnight. Kotter articulates the vision of transformation change management practices in this vignette:

“Over the past decade, I have watched more than 100 companies try to remake themselves into significantly better competitors. They have included large organizations (Ford) and small ones (Landmark Communications); companies based in the United States (General Motors) and elsewhere (British Airways); corporations that were on their knees (Eastern Airlines); and companies that were earning good money (Bristol-Myers Squibb). These efforts have gone under many banners: total quality management, reengineering, right sizing, restructuring, cultural change, and turnaround. But, in almost every case, the basic goal has been the same: to make fundamental changes in how business is conducted in order to help cope with a new, more challenging market environment. A few of these corporate change efforts have been very successful” (Kotter, 2002, pg. 1).

In his Strategy for Change Management, Kotter (2002) adopts an 8-step process for planning what he calls a Transformation Model for leading change. He describes the eight step process to risk mitigation of organizational errors: 1) Establish a sense of urgency; 2) Create a guiding coalition; 3) Develop a vision and strategy; 4) Communicate a change vision; 5) Empower broad-based action; 6) Generate short-term wins; 7) Consolidate gains and produce more change; 8) Anchor new approaches in the organization’s culture.

Consideration of actors in the Transformation Model are likely to be targeted administrative or operations managers, or process owners responsible for different nodes in the operating system of an organizational system or knowledge database. Exercises responsive to this application may come from various levels of management. The Transformation Model is applicable to organizations which are: 1) Developing Social Construct; 2) Oriented Social Construct; 3) and Pluralistic Social Construct types. This model may not be suitable for organizations that are in pursuit of prompt change. As Kotter points out, change needs time, and the transformation technologies employed in expert change management planning processes are meticulous, and subject to rearticulated decisions in the management chain either momentarily, or long term. The range of detriments posing liability to an organization at any stage must be integral to flexible transformations. Tables 8-11 show that change models all address the people side of change but they usually differ in their strategies according to metaphors or organizations.

ADKAR

Table 3

| Strengths | Weakness |

| Non-linear

Focuses on people Lots of opportunity for creativity |

It is general and requires the intervention of skill facilitators to interpret realistic situations |

System Approach Model (Systems approach to management, Michael. C. Jackson, 2000)

Table 4

| Strengths | Weakness |

| Looks at all subsystems, their interrelationships and interaction between the subsystem and the environment

Viewed organizations as systems which had needs, functional imperatives and were dependent of subsystems for survival

Organizations were open systems dependent on environment |

Failed to deliver scientific explanations for statistical correlation

Exhibits managerial bias

It cannot properly explain change and conflict

Prescriptions to improve managerial capabilities were ill founded

Neglects goal oriented activities. |

Transformation Leadership Model:

Table 5

| Leadership oriented model

Leaders identify real incentives to encourage employee participation, motivation and growth

Emphases on organizational culture, mission and strategy for change |

It has a complicated framework

Absence of process considerations |

Transformation Model:

Table 6

| Strengths | Weakness |

| Clear steps to guide the process

Easy to understand Fits well into culture of classical hierarchies Buy in of employees as the focus of success |

Linearity may increase complications

Once process starts it is difficult to reverse

Model is top down and gives no chance for creativity or true participation

Can lead to frustration within employees if the stages of individual needs and grief are not properly addressed |

Human factors in change organizations

Organizational change is almost inevitable. However, research has showed in the past years that only one third of change initiatives receive any success. The organizational change may be due to various reasons like reengineering, implementation of total quality management or change of corporate culture. Employees feel uncomfortable to change – they resist and sabotage the change management plants. The lack of support, participation and commitment from employees result in failure of processes. This further aggravates employee grievance, loss of motivation and cynicism. The reasons for failed attempts resulted when organizations minimise individual and the cognitive- affective nature of organizational change.

Human factors that prevent organizational change

Employees have deep attachments to their work group, organization, and their method of working. Change is constant and it would be wise for employees to learn how to manage change. The potential of the employee to understand and adapt to changing work conditions is important for organizational and individual survival. Lack of communication, misinformation, confusion and insecurity pledge them more in the process of resisting the change initiative. They feel neglected, ignored and cheated. This negative attitude leads to massive failures in organization change processes. According to Folger and Skarlicki (1999), “organizational change can generate scepticism and resistance in employees; making it sometimes difficult or impossible to implement organizational improvements” (p. 25). Any management’s ability to achieve maximum benefits from change depends in part of how effectively they create and maintain a climate that minimizes resistant behaviour and encourages acceptance and support. (Coetsee, 1999, p. 205)

Resistance to change

According to many organizational theorists, resistance as an inevitable outcome or phase of change has become a self-fulfilling prophecy in many organisations attempting to meet the demands of globalization. It is estimated that between 60% and 80% of people in an organisation are neither resistant nor ready. Their reaction depends on how the transition is facilitated. Unfortunately, most organisations fail to adequately address the human dynamics of the change, which results in resistance. Simply put, resistance is a response to an unresolved issue or problem that is manifested in attitudes, feelings or behaviour. In this context it is not the change that is being resisted but the uncertainty and apprehension that comes when individuals lack the readiness needed to move through the continuum of change. With many organisations undergoing three or more simultaneous changes, with limited resources, the current focus on managing resistance is not sustainable. Table 7 illustrates the levels of resistance to organizational change.

Table 7

Organization-Level-Resistance

| Power and Conflict | Resistance to change due to power and conflict is usually seen when a change has diverse effects on different departments. It may be beneficial to one department while harming the other within the organization. |

| Functional Orientation | Resistance to change may occur due to differences in functional orientation. This happens when employees with different functions evaluate and see problems differently. Thus, it is difficult to bring them to a joint consortium regarding change. |

| Organizational Culture | Resistance due to organizational culture occurs when organizational change hampers the norms and ethics followed by employees in the original structure. |

Group-Level-Resistance

| Group Norms | Resistance due to group norms occurs when there is change related to altered interaction between group members due to changes in assignment and role relationship within. |

| Group Cohesiveness | This Resistance occurs because employees of a cohesive group wish to keep all the information, tasks and responsibilities within the same group. |

| Groupthink and Escalation of Commitment | Resistance due to groupthink and escalation of commitment occurs when they respond to negative rumour just to be in consortium with other members. |

Individual-Level-Resistance

| Uncertainty and Insecurity | Resistance due to uncertainty and insecurity occurs because employees are uncertain about the outcomes of the change. |

| Selective Perception and Retention | Resistance due to selective perception and retention occurs when employees try to assume and portray their interpretation of the change process. |

| Habit | Resistance due to habit occurs when employees do not want to compromise with their daily habits. |

Exhibiting Resistance to Change

| Passive Resistance | Passive resistance refers to negative behaviour and approach regarding the change. |

| Active Resistance | Active resistance refers to active opposition against change. Strikes, absenteeism and lethargy are the examples of such behaviour. |

| Aggressive Resistance | Aggressive resistance refers to behaviour that hinders and blocks the change process. Typical examples are subversion or sabotage (Bolognese, 2001). |

Table 7: Levels of Resistance to Organizational Change

Negative aspects of Resistance to Change

Lack of Commitment by the Employee

Organizational commitment can be defined as intimate emotional exchange between the employee and organization. Organizational change can detach an employee from the organization. While large scale transformation can reduce the commitment of the employee to the company. It usually happens when an organization mainly focuses on the structural aspects of change and ignoring the guidance and support aspect of its personnel. Lack of commitment is a major obstacle in the process of organizational growth.

Decrease productivity

Reduction in Productivity: Uncertainty, anxiety and stress leads to less work being done gets done by employees who come to work. In an environment of ambiguity and confusion, individuals may withdraw support and become self-protective. Superiors may blur and inconsistent information. Working relationships suffer, and so do the overall tempo of the workforce. Thus in the change process productivity suffers and so do hinder the organizational change process.

Absenteeism

Uncertainty in the work and being over protective about their jobs stresses the employee. It results in burnout, and many work days are missed. Employees start looking for other personal and professional diversions as the transition tries to take place. The employee is thus a distracted individual, and it is very difficult for him to concentrate on change effort. He is either mentally or physically absent while his potential and critical input is required. Such a waste of the resource not only discourages the team members but also instills permanent damage to the organizational change process.

Positive aspects of resistance

Insightful and well intended criticism, debate and disagreement, may necessarily not imply resistance. It may be a qualitative action for better alternatives or action. Piderit (2000) says that certain instances of negative response to change may be the outcome of ethical values of the employee. Again employee resistance may force organizations to rethink, proposed change initiative. It also serves as a filter to help the organization understand and adapt a model suitable as per the prevailing conditions. “Resistance is simply a very effective, very powerful, very useful survival mechanism.” (Jager 2001, p. 37)

Conclusion

In this section the KAM addresses four (4) organization change management models: ADKAR, Transformation Model, Systems Theory and Transformation Leadership Model, and comes to the conclusion that different models were developed to meet the challenges of stratified change. Each model has weaknesses and advantages. However, they have adapted and formulated and had been of extreme use to the organizations. ADKAR is but one of several approaches from which samples and can be used in organizations that opt for quick change while Kotter (Transformation) model can be used in organizations that emphasize long term change initiatives. Systems theory is perfect for organizations of scale in assessment of systems capabilities, and Transformation Leadership model is ultimately the most proximate to a comprehensive leadership-centric approach.

Annotated Bibliography

Aziz, R.A., Ishak, N.A., Ghani, P.A. & R. Othman (2009). Transformational leadership towards world class University status: Journal of Global Management Research. Retrieved from: http://www.gmrjournal.com/FichierPDF/v5n1art7.pdf

A meta-analysis replicating standing empirical research on transformational leadership and its correlation to organizational and leadership effectiveness, the brief five page article discusses how transformational leaders believe in the need for a change, and the organizational impact that they foster through group acceptance, the study looks at ‘trust; in organizational environments from the perspective of Malaysian ‘World Class Status’ in the university environment, by application of the ‘EGM-PLU’S Model which attempts to build a ‘respect’ measurement in regard to motivational forces.

Transformational aspects of the study investigate how leaders change the beliefs and attitudes of followers so that they are willing to perform beyond the minimum levels specified by the organization. Based on a seven (7) study aggregate comparison, methodological consideration on the research attempts to distinguish between common traits and the proposed conceptual framework to look for better systems of leadership to cope with emerging global challenges and development. Citing over one hundred empirical studies, the research looks at how transformational leadership has been found to be typically correlated to organizational and leadership effectiveness.

Definition of ‘transformational leadership’ is determined by a ‘belief’ or system of pragmatic gestures applied in response to ethical or policy directives understood to the ideological basis for change management practices. Visionary articulation of an organizational future with shifts in the global economy, and most specifically the futures market, might find interpretation in the study. While such proscriptions for the use of the research might be exceeding original hypothesis, recommendations within the work intend to “foster the acceptance of group goals, and provide individualized support” toward greater team impact.

Brown, E (2005). Making inspired leader. Journal of Jewish Communal Service, 81(1/2), 63-71.

Brown being one of the famous propagators of leadership in religion- tries to convey the message to the leaders- that inspirational motivation is the secret to lead the followers. The query constitutes an analysis of ethical and systemic methods of mapping emotional contribution toward better models of protocol based on communicative feedback between Jewish leaders and colleagues in philanthropic organizations. The article focuses on the capacity of leaders to employ emotions as a catalyst for change. Leaders, as Brown argues, do not manage followers but ‘create’ them.

Pointing to the lack of inference to teaching emotive techniques within most leadership manuals, she maintains that the ‘crisis in inspiration’ is due to the fact that the entire lexicon of leadership practice has been built on a model of competitive interests that do not necessarily lead to formative relationships of guidance. The emphasis on ‘dynamic’ and ‘aggressive’ figure heads that how to rule over all others for their team is in fact, the crux of the crisis. Looking at the core values underscoring Israel’s theocratic movement of Zionism, Brown’s work addresses the impact and shortcomings of a population driven primarily by text and ritual, but argues that shared identity in a physiognomy of a leader is unavailable. Conversely, as she puts it, Jewish organizations often do not have the appropriate mechanisms in place toward check and balance of senior professionals. The result is that Jewish leaders do not receive feedback by way of disciplined and expected channels.

In reference to the current KAM study, Brown’s argument that Israel still does not have leadership based on inspiration should be looked at critically beyond the philanthropic sphere, as such an existing clause within social thought offers counter to extension of the theocracy’s bureaucratic authoritarian motives; which currently circumscribe institutional authority over personalized charisma. The decision to avoid such emotive or flamboyance versus a ‘rationalized’ model of leadership has much to do with the dangers of zealotry present within radical national socialist leadership – as seen in Nazi Germany. Interestingly, the right of the Zionist state to act on behalf of Israel’s citizenry, and its formative foreign policy negotiations – and including war – does present a parallel to this denunciation of an individualized model of leadership, in that the sovereign right of the state advances territorial claims without recognition of a democratic, international community as it asserts the nation’s ‘will to power’ in perpetuity.

Burke, W.W (2007). Organization change: Theory and practice. (2nd Ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

In this book, Burke compares the models of different theorists. Among all the evaluations he chooses the Burke-Litwin model as his preferable choice for implementation in change management processes of organizations. The model is written as a guide for change leaders. Change efforts are regarded as proceeding like spirals rather than circles to depict their ongoing chaotic nature – and the view that what is learned from each phase of a change effort can be rolled into subsequent phases. In this way, organizations are transformed into learning organizations that ‘learn’ from experience.

As an organizational theory, the author cites that leaders are the main pillars in the path of organizational change. Interested in the development of organizations by way of a volitional leadership and visionary thought, the author suggests that effective executive management should be equipped with skills of strategic decision making that include: Conceptual complexity; Behavioral complexity; Strategic Decision making appropriateness – including intellectual capacity to structure and oversee activities; and Visionary and Inspirational qualities.

Prioritization of the individual as the core of priority in organizational competencies is underscored in the work, as the author designates the human factor as organization’s most important asset; and management strategies in consortium with those material and motivational needs. Ultimately, leaders are responsible for recognition of employee value, and commitment, trust and long-term motivation can only be achieved if a high level of interest in the change process is present so that employees may air difference of opinion, and engage and integrate adequate into organizational culture, and including adjust to priorities and preferences which are central to his or her ‘management style.’

Burke, W. W., Dale, G. L., & Jill, W. P (2008). Organization Change: A Comprehensive Reader.

This edited volume is dedicated to change management, organization transformation processes, and transformational leadership models. The seventy five chapters of the book offer critical reading from the field of organizational theory. The most pertinent are the organization development philosophies presented by luminaries such as Drucker, Schein, Tichy, Weick, Bennis, Hamel, Gladwell, Tushman, Quinn, Beckhard, O’Toole, Bridges and Argyris.

A comprehensive text offering much in the way of comparative framework, the book fosters dialogue with scholars and business professionals interested in the epistemological foundations of a discipline meant for the twenty-first century. Emphatic in positioning, this tome is designed toward ontological development within a field that has a number of teleological roots. Seminal perspectives are important for any serious academic query, and representation of salient thought within the discipline supports theoretical structuring in application to research within organizational theory, and in this case leadership.

A key reference to primary research, the work serves as a guide for theory-based, replicable studies, and encourages multiple positions within the KAM to form a communicative praxis toward furtherance of the discipline’s intellectual integration with global change management leaders, and ultimately publication.

Harris, A. (2006). Opening up the ‘Black Box’ of leadership practice: Taking a distributed leadership perspective. International Studies in Educational Administration, 34(2), 37-45.

Harris emphasizes the concept of distributive leadership looks at the possibilities of horizontal direction in school administration. The article addresses the capacity of departmental leadership integration in schools as a mechanism for increase in student and institutional performance. Interested in the advancement of knowledge sharing within organizations, the distributive model of ‘parallel leadership’ holds promise in that all actors are put into a network of service to the institution with student achievement as the core goal. Although the model presents an alternative to traditional hierarchical authority structures in learning institutions, Harris argues that such vertical approaches have rendered institutions incompetent in addressing real challenges within the learning environment. Administrative participation within the distributive approach requires oversight in vision as principals are inevitably responsible for the general cultural and structural aspects of those institutions.

Researched evidence on distributive leadership in academic institutions reveals that improvements are sufficient to suggest recommended application of the model, but that such planning should be cognizant of both micro and macro-political barriers to such changes in structural and cultural practices. Compensatory strategies are not discussed extensively within the article however, mention of the value of salary index as a direct correlate to willingness to participate fully in organizational transformations is likely. Tacit consent is a significant issue, as complete adherence to such policies may be varied. Democratic approaches to leadership have double impact, in that students observe and benefit from lateral relationships of authority. Dialogue is central to shared leadership settings, and quite obviously the basis of democratic education in general.

Heney, P (2008). Managing employees takes sense of style. Hotel and Motel Management, 223(13), 6. Retrieved from: http://www.hotelworldnetwork.com/coaching/managing-employees-takes-sense-style.

Heney has a long association in the management role in the hotel industry. His experience sheds light on the various culture mixes that the leadership has to face. Thus people with diverse needs flock the organization and it is the mastery of the leader to synchronize them and eventually motivate them to work efficiently. The work looks at Douglas McGregor’s concept of X and Y managers and points to the distinctions in managerial style leading to perceptions that employees are either ‘unable to work without supervision’ or that they will avoid working without constant monitoring and/or threats by an organizational manager.

According to the author, X managers tend to focus on employee orientation rather than company policy, and look to how employees adjust to jobs in response to the need for job security. Job security, then, is perceived as an independent variable that must be subject to psychological reconfiguration by the X manager, rather than met through mere compensatory or other benefits.

The impact of such beliefs by McGregor’s X managers has been a topic of much interest in the past decade, and as the author describes, change management practices cannot meet the competitive bar without redirection of management staff versus employee oversight. Managers that proceed toward change with negative conduct such as yelling and unconstructive criticism ultimately fail in the current climate, says Heney, and lack the required training needed to promote individual creativity, inspiration and imagination on the job – all highly valued criteria for responding to change management challenges in the global economy.

Periyakoli, V.S (2009). Change management: The secret sauce of successful program building. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 12(4), 329-330. DOI: 10.1089=jpm.2009.9645329

Periyakoli, one of the proponents in Palliative medicine, formulated the use of a leadership model to take care of the patients. Here the doctors assume the role of leaders. Alternative to the mainstream of biomedicine, Palliative provides a nascent environment for change leaders in the medical field to forge new pathways in health care systems and care provision. Based on Dr. Diane Meier’s framework for clinical care program expansion developed at The Center for Advancement of Palliative Care (CAPC), the author looks to Kotter’s 8-Step Model for Change Management as a model of requisite tools for application of Meier’s approach.

Derived from change theories in the field of organizational management, Kotter’s change management model offers a step-by-step approach to operationalized systemic transformation in the context of palliative care initiatives:

Step 1: Establish a sense of urgency with stakeholders with an eye toward reasonable solutions. Example: integration of institutional on patients as a means of ‘sharing’ referred cases;

Step 2: Create a coalition for change with leadership that can secure commitments;

Step 3: Develop a vision and strategy;

Step 4: Communicate the change vision to others;

Step 5: Identify and overcome resistance through diagnostic of organizational findings;

Step 6: Generate short term successes;

Step 7: Consolidate gains and produce more change;

Step 8: Anchor the changes in the institutional culture.

As the authors suggest, consider of Kotter’s model in a Palliative care setting requires thorough organizational analysis with adequate assessment tools and deepened IT networks.

Poole, M., S., & Van, De. Ven (2005). Handbook of Organization Change and Innovation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

The book analyzes episodic or partial change versus total change management within organizations, and addresses pertinent theories directed at the evaluation of individual development and creativity as an essential element for motivation in organizational change. Leadership is interpreted as a strategy derived from innovation, intellectual saliency, and visionary interpretation of the systemic possibilities for transformation in organizations.

Some of the theoretical positions discussed include: socialization and interpersonal interaction theories; learning organization theories; contingency theories; population and community ecology theories; cultural theories; institutional design and diffusion perspectives; and intervention theories. Analytic frameworks vary according to theoretical perspective, and a range of change agent possibilities are addressed with strategic planning in mind. Macro, distant and global perspectives are looked at in response to short-term planning initiatives for triggering replacement and substitution of invaluable forces in existing systems or structures that might benefit from deep, yet rapid interventions.

Micro, close and local potentialities offer situation analyses and solutions toward long-term objectives in environments where there are emergent patterns, learning objectives, recurrent interactions, and the need for improvisation or translation is necessary for crafting horizontal decision making models for sustainable growth. The book includes four (4) basic motors for organizational change: 1) Life-cycle model based on phases of growth; 2) Teleological enactment of a social construction(s); 3) Dialectic tools for creating solution out conflict; and finally 4) environmental model looks to external resources, and in particular competition as the natural basis for the development of organizational change.

Riordan, C.M., & Vandenberg, R.J., & Richardson, H.A (2005). Employee involvement and organizational effectiveness: An organizational system perspective. Human Resource Management, 44, 471-488.

The study empirically investigates the relationship between Employee involvement and organizational effectiveness. The authors used strategic data from insurance companies and evaluated results on the basis of the study. Results indicated the positive relationship between organizational effectiveness and leadership style. According to the authors, there are twenty (20) competencies present in highly effective managers, and without exception most if not all, should be exercised in decision making and oversight of organizational activities.

Ideally, leaders should possess attributes that reflect their ability to care for employees and the organization in an integrated fashion. Executive managers are typically both ‘Providers’ and ‘Protectors’ of their teams, and deflection of problems from an organizational group may be just as important to the health of an organization, as visionary potential. Nevertheless, part of problem solving is resource in a shared vision and its articulation in company procedures and policies as an instrument of mitigating undesirable circumstances and for promotion of overall organizational sustainability.

Transformation is logically dependent upon translation of a leader’s educated vision, and the executor’s ability to reach action through the praxis of communication as a vehicle for measuring, and implementing strategies for meeting goals and objectives. A ‘can do’ attitude says the authors, is the driving force behind team action. A combination of competence and enthusiasm creates the psychological dimension behind successful implementation of strategist methodologies. Delegation of tasks is an essential, if not traditional criteria for completing the circle of work, and how managers think through allocation of activities is evidence of a leader’s capacity to communicate the ‘big picture.’

Rothwell, J. W., Stavros, J.M., Sullivan, R. L., & Sullivan, A. (2007). Practicing Organization Development: A Guide for Leading Change.

Rothwell stresses the intervention of a development practitioner. He observed that such intervention helps organizations to chalk down strategies so that they have little probability of failure. A seminal work, first published in 1995, the proscriptive methodologies contained in the Guide are a classic in change management theory. Envisioned as a roadmap for the navigation of organizational transformation, the authors look to various practices currently employed in global companies that have been forced by market or by thought to change rapidly to meet developments in emergent technologies and other cutting edge sources of professional influence.

This early change management prospectus proposes to serve as a model for business professionals whom are in the planning stages of organizational transformation. Written with ‘goal’ centered, strategic planning execution in mind, the author develops a theory that is quite compatible with the rapid capitalization that accompanied globalization in the 1990s. Matching financier perspectives on flexible labor, the author maintains that flexible leaders will ultimately be the most competent, if not the most observant in vision and operational planning.

Integral to a project on transformation leadership, Rothwell’s work in offers historical retrospect, as well as timeless insights into the potential of that application of structural logics within organizational change management may provide. Inspiration is at the core of leadership, despite the field’s larger emphasis on structural competencies, and his discussion allows scholars to see convergence in change management and transformation leadership from a principled position that is well employed in the current policy driven environment.

Sahoo, A (2008). Leaders and their teams: Learning to improve performance with emotional intelligence and using choice theory. International Journal of Reality Therapy, 27(2), 40-45.

Sahoo observes that an emotionally intelligent leader is the most sophisticated and real form of leadership today. The leader with his traits must be emotionally connected with his followers to achieve their loyalty and reverence. Although the paradigm appears loosely connected to ‘personality type’ the author argues that the continuity within a leader’s thought processes as it is exhibited in the work environment, and especially in response to processes of globalization is important because ‘improvements’ to team efforts and organizations as a whole can only be met through coherent dialogue and direction.