All papers examples

All papers examples

Disciplines

- MLA

- APA

- Master's

- Undergraduate

- High School

- PhD

- Harvard

- Biology

- Art

- Drama

- Movies

- Theatre

- Painting

- Music

- Architecture

- Dance

- Design

- History

- American History

- Asian History

- Literature

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- English

- Linguistics

- Law

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Ethics

- Philosophy

- Religion

- Theology

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Economics

- Tourism

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- Psychology

- Sociology

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Anatomy

- Zoology

- Ecology

- Chemistry

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Geography

- Geology

- Astronomy

- Physics

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- Internet

- IT Management

- Web Design

- Mathematics

- Business

- Accounting

- Finance

- Investments

- Logistics

- Trade

- Management

- Marketing

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Technology

- Aeronautics

- Aviation

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Healthcare

- Nursing

- Nutrition

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Journalism

- Public Relations

- Education

- Educational Theories

- Pedagogy

- Teacher's Career

- Statistics

- Chicago/Turabian

- Nature

- Company Analysis

- Sport

- Paintings

- E-commerce

- Holocaust

- Education Theories

- Fashion

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Science

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

Paper Types

- Movie Review

- Essay

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Assessment

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Case Study

- Coursework

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Assessment

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Case Study

- Coursework

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- Essay

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Interview

- Lab Report

- Literature Review

- Marketing Plan

- Math Problem

- Movie Analysis

- Movie Review

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Online Quiz

- Outline

- Personal Statement

- Poem

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Quiz

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- Resume

- Speech

- Statistics problem

- SWOT analysis

- Term Paper

- Thesis Paper

- Accounting

- Advertising

- Aeronautics

- African-American Studies

- Agricultural Studies

- Agriculture

- Alternative Medicine

- American History

- American Literature

- Anatomy

- Anthropology

- Antique Literature

- APA

- Archaeology

- Architecture

- Art

- Asian History

- Asian Literature

- Astronomy

- Aviation

- Biology

- Business

- Canadian Studies

- Chemistry

- Chicago/Turabian

- Classic English Literature

- Communication Strategies

- Communications and Media

- Company Analysis

- Computer Science

- Creative Writing

- Criminal Justice

- Dance

- Design

- Drama

- E-commerce

- Earth science

- East European Studies

- Ecology

- Economics

- Education

- Education Theories

- Educational Theories

- Engineering

- Engineering and Technology

- English

- Ethics

- Family and Consumer Science

- Fashion

- Finance

- Food Safety

- Geography

- Geology

- Harvard

- Healthcare

- High School

- History

- Holocaust

- Internet

- Investments

- IT Management

- Journalism

- Latin-American Studies

- Law

- Legal Issues

- Linguistics

- Literature

- Logistics

- Management

- Marketing

- Master's

- Mathematics

- Medicine and Health

- MLA

- Movies

- Music

- Native-American Studies

- Natural Sciences

- Nature

- Nursing

- Nutrition

- Painting

- Paintings

- Pedagogy

- Pharmacology

- PhD

- Philosophy

- Physics

- Political Science

- Psychology

- Public Relations

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Religion

- Science

- Shakespeare

- Social Issues

- Social Work

- Sociology

- Sport

- Statistics

- Teacher's Career

- Technology

- Theatre

- Theology

- Tourism

- Trade

- Undergraduate

- Web Design

- West European Studies

- Women and Gender Studies

- World Affairs

- World Literature

- Zoology

Terry Stops Are Unjust and Ineffective, Term Paper Example

Hire a Writer for Custom Term Paper

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

The fourth amendment to The United States Constitution states “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized (U.S. Const., amend. IV).” This amendment was written by the framers of the Constitution to ensure every citizen’s equal protection under the law and protection from unwarranted government intrusion. The idea was very much influenced by the colonists’ experiences of random and forceful invasion by the Queen’s soldiers under faulty and uncertain pretenses. However, the right of the people to be free from unreasonable, unwarranted searches has received varying levels of protection from the United States court system depending on jurisdiction. This represents a violation of one the main principles upon which our country was established. The violation is very much prevalent in the heart of the country’s greatest city, New York.

The framers featured the fourth amendments in the Bill of Rights as a necessary and important defense of the individual’s rights against the colossal power of the federal government. More specifically, it was intended to determine and regulate police actions. The intentional vagueness of the amendment leaves the task of determining a reasonable search up to the Supreme Court. The most influential case regarding the regulation of police procedure is Terry v. Ohio. In 1968, the court ruled that a police officer may, without a warrant or probable cause, seize a person based upon a reasonable belief that “criminal activity may be afoot. “Furthermore, the Court stated that police officers may then conduct a cursory search of that person if they have reason to believe the individual “may be armed and presently dangerous. “Under Terry, the Court stated that the officer does not need to establish probable cause to arrest in order to seize an individual to investigate suspected criminal activity. Instead, the officer must only demonstrate a “reasonable suspicion” of the person’s involvement in criminal activity. “Reasonable suspicion” is a lower standard than probable cause, and requires only a “minimal level of objective justification for making the stop,” based upon “specific and articulable facts . . . taken together with rational inferences from those facts.” The decision created a more flexible standard for the reasonableness of stops and searches. The court justified the decision by citing the public’s interest in actions taken by police to prevent crimes from occurring.

In 1985, the court expanded the permissibility of Terry stops by including criteria for completed crimes. United States v. Hensley stated that police officers may make investigative stops of individuals believed to be involved in a competed felony. However, the court left the question of the reasonableness of searches of individuals believed to be involved in misdemeanors unanswered. This question has been answered differently among lower court circuits, with some considering misdemeanor stops to always be unreasonable and others using a “totality of circumstances” test to balance interests of effective law enforcement with unfair intrusion of the individual. In his article for the St. John’s University Law Review, Nicolas Alioto proposes a new rule that is consistent with the court’s reasoning in Terry and Hensley and addresses the varying opinions of circuit courts by establishing a better balance between effective law enforcement and appropriate protection of individual rights. Under Alioto’s proposed rule, “Terry stops conducted for the investigation of completed misdemeanors are presumptively unreasonable unless the police officer can point to specific facts that would lead a reasonable officer, in his position, to conclude that failure to take immediate action would result in physical harm, either to himself or to a member of the general public. This rule adopts the reasoning employed in both Terry and Hensley and can be easily and consistently applied by the police. The proposed rule provides law enforcement officers with the appropriate amount of flexibility to act to prevent imminent physical harm without having to first weigh a myriad of ambiguous factors in the heat of the moment; yet the rule still provides better protection of Fourth Amendment rights than either of the methods currently employed”.

Alioto’s proposed role sets a better framework for determining reasonable stops by relying on the ability of a trained officer to determine that failure to stop an individual would result in public harm. The rule also highlights that stops for suspicion of a lower class, non-violent misdemeanor provide avenues for unreasonable violations of individual rights. These kind of suspicions are often difficult for law enforcement to validate and can occur frequently in a highly populated urban area such as New York City.

The New York State legislature passed the “stop and frisk statute” in 1964 in response to the Supreme Court’s ruling on Mapp v. Ohio earlier that year. The decision changed the history of police procedure when it extended the exclusionary rule to the states, barring illegally searched evidence from being used as evidence in state courts. New York State felt the need to clearly elaborate on law enforcement search procedure and statutes. The leaders of the Police Department had a heavy influence inside the state legislature and pressured state senators to approve a revised statute for stop and search procedures. The result was the “stop and frisk statute” that authorized officers to “stop and search individuals suspected of past, present, or potential criminal conduct and, when officers suspected danger, conduct a search for weapons.” Anything found in these searches was considered valid in court. Critics of the statute argued that it placed too big of a burden on the quick judgment of officers. The Police Department combatted these concerns by emphasizing the training and professionalism of officers. This “Police Professionalism movement” presented a better view of Police officers and ultimately won the approval of stop and frisk policies. The movements’ success was said to have an effect on the justices’ decisions in Terry.

In the 1960’s the courts changed the fourth amendment exception of probable cause to suspicion. The new exception subsequently brought about an expansion of police investigative authority around the nation. The public’s attitudes towards these expansions generally supported it. The social conditions of the time had a lot to do with public sentiment on the importance of law and order. Crime was on the rise, college students were rioting on campuses around the country, and the country was seeing its leaders gunned down by assassins. In order to deal with these problems, the New York City Police department underwent a series of administrative changes to better improve rank and file accountability. These changes were mainly jumpstarted by the courts mandates that the department’s record keeping be held to the utmost standards, and that rank and file accountability be at an increased level – to ensure departmental transparency on all levels. Despite their intentions, there are numerous studies that suggest their efforts have not been effective.

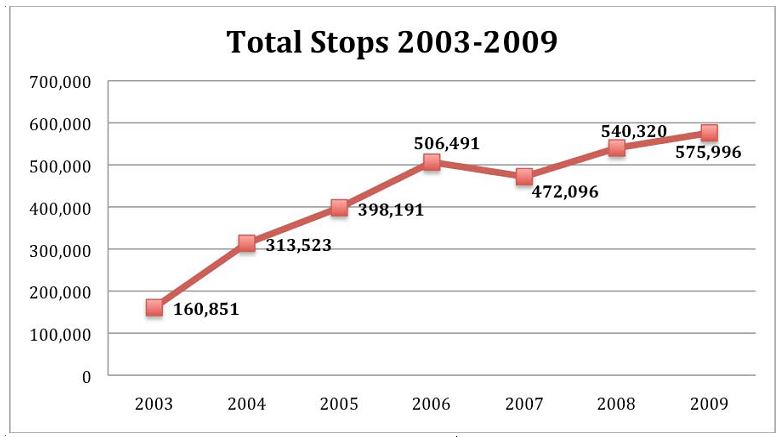

In Jennifer Trone’s article “The New York Police Department’s Stop and Frisk Policies Are They Effective? Fair? Appropriate?,” She documents the 2010 New York City Bar Association’s Council forum held to discuss policing practices. The main topic of the conversation was the use of what’s known as stop and frisk, or Terry Stops. The debate over whether these stops are racially bias, or a viable method of reducing crime was confronted from multiple perspectives. The author notes that, “in introducing the subject of stop, question, and frisk, Jeremy Travis presented a slide (copied on the following page) illustrating a dramatic increase in the number of stops annually in New York City – from 160,851 stops in 2003 to 575,996 in 2009, an increase of more than 300 percent in six years (Trone, 2).” The chart below demonstrates this growth in stops between 2003 and 2009.

(Trone, page 3)

As the chart shows stops have been consistently increasing in number since 2003. Further data found the supports the notion that this trend has continued, “Between January 2006 and March 2010, the police made nearly 52,000 stops on these blocks and in these buildings, according to a New York Times analysis of data provided by the Police Department and two organizations, the Center for Constitutional Rights and the New York Civil Liberties Union (Rivera, Backer & Roberts, 1).” The data clearly shows that theses tops are increasing over time. This generates the debate of why they are increasing.

In Talk Left Jeralyn attributes to the election of Mayor Bloomberg as one of the distinct factors resulting in the increase, noting that during his tenure, more than 90% of individuals stopped turned out to be innocent. In her article she states that “A new study by the ACLU has found New York City cops initiated street stops (aka Terry stops, stops and frisks or interrogations) 684,330 times in 2011, an increase of 600% since Bloomberg took office in 2002 (Jeralyn, 1).”

“Of the stops, 90% were “completely innocent” (no arrest or summons issued) and 87% were Black or Latino (Jeralyn, 1).”

Numerous criminal justice researchers question whether stops have increased in number over time due to the fact that “they have become a proxy for the productivity of individual officers, precincts, and the police department as a whole (Trone, 3).” This suggests that the NYPD culture has established a protocol for identifying these stops as their main metric to measure productivity. If all respective precincts share a stop quota, it would mean that the actual procedure of stopping citizens is less about preventing crime directly but more about doing police work indirectly through a numbers game of staying active. This could arguably be an effective method of reducing criminal activity so long as it’s indiscriminate. The problem is data shows that it’s not indiscriminate, but in fact there is a significant racial bias associated with these stops. As the author notes, “Fagan also expressed concern that the NYPD is using stops as a system for gathering intelligence, amassing a large and growing database of information about mostly Black and Hispanic New Yorkers (Trone, 3).” In addition to this being a cultural concern, data also shows these stops are ineffective.

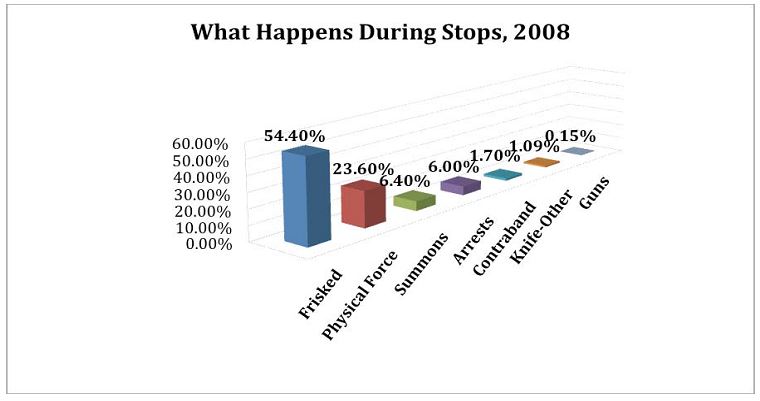

As Trone points out, Jeremy Travis presented this slide at the start of the forum. The data shows that in 2008 (6%) of the stops resulted in an actual arrest, (6.40%) resulted in a summons, (0.15%) resulted in the confiscation of a gun, and (1.09%) resulted in the recovery of a knife or another form of weapon (Trone, 6).

(Trone, 6)

From the data presented above, the article makes this conclusion, “For Jeffrey Fagan, these low “hit rates” are proof that stops are inefficient (Trone, 6).”

In their analysis of Stop Frisk, The New York City Liberties Union noted that there is no real research to suggest that stop and frisk has been effective, but there are numerous indicators that suggest it is ineffective. In the study they note that, “the small number of arrests, summonses, and guns recovered demonstrates that the practice is ineffective (NYCLU, 1).” While there are no in-depth studies to imply Stop and Frisk is a valid crime suppressant, there are some indicators that Bloomberg’s influence could have had a positive effect. The New York City Liberties Union does point out that, “The year before the mayor took office there were 649 murders in New York City. In 2011, there were 526 murders. This 19 percent drop is important, but to suggest that murders were cut in half because of stop-and-frisk is simply wrong (NYCLU, 1).” Their conclusion that it’s wrong to read this murder rate drop as an indicator of ‘stop-and-frisk’s’ success comes from the fact that stop-and-frisk’ has not reduced any number of individuals who were victims to shootings in 2002. As they note, “In 2002, there were 1,892 victims of gunfire and 97,296 stops. In 2011, there were still 1,821 victims of gunfire but a record 685,724 stops (NYCLU, 1).” Their data further supports arguments that these stop and frisk procedures are racially bias in that just in Park Slope New York alone, where their study was focused, Blacks and Hispanics made up 24 percent of the population but represented 79 percent of the stops (NYCLU, 1). Anyone who would interpret this data on face value alone would identify it as discrimination.

In sum, despite the fact that the United States Constitution protects against unwarranted search and seizures, New York has significantly breached the stipulations of the 4th amendment through their use of Terry Stops. While Mayor Bloomberg and his supporters suggest this tactic has significantly reduced the New York City crime rate, actual data negates this notion and also makes valid the argument which much of the policy’s opposition shares that to stop-and-frisk is racially bias. This places NYPD Terry Stops in the position of being Unjust and ineffective.

Work Cited

Jeralyn. “NYPD Street Stops Soar 600% Under Bloomberg.” TalkLeft: The Politics Of Crime. Talkleft.com, 16 Feb. 2012. Web. 15 Dec. 2012. <http://www.talkleft.com/story/2012/2/16/14734/4700>.

NYCLU. “Stop And Frisk Facts.” Stop and Frisk Practices. American Civil Liberties Union of New York State. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Dec. 2012. <http://www.nyclu.org/issues/racial-justice/stop-and-frisk-practices>.

Rivera, Ray, Al Baker, and Janet Roberts. “A Few Blocks, 4 Years, 52,000 Police Stops.” The New York Times, 11 July 2010. Web. 15 Dec. 2012.

Trone, Jennifer. The New York Police Department’s Stop and Frisk Policies Are They Effective? Fair? Appropriate? Summary of a NYC Bar Association Forum March 9, 2010. Rep. New York: n.p., 2010. Print.

US Const. amend. IV. Print.

Stuck with your Term Paper?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Tags:

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

writing help!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee