Adaptation and Implementation of eMAR, Research Paper Example

Abstract

Implementing eMARs (Electronic Medication Administration Records) as an integral part of critical care unit (CCU) protocol is a multifaceted transition process that requires large scale integration changes in the medical industry. This is a transition that focuses on the ultimate improvement and maintenance of electronic point-of-care medication administration records (eMARs) and focused quality improvement (QI) efforts, as they relate to one another during implementation by CCUs. Critical care units are specifically equipped for the treatment of individuals who have intensive life threatening conditions, but medical errors are still a common occurrence. In a study published by The Department of Critical Care Medicine at the Foothills Medical Centre, it was found that, critically ill patients admitted to a CCU experience an average of 1.7 medical errors each day. It was also found that many patients encounter a plausibly life-threatening error during their stay. Adapting to an eMAR based system can significantly reduce the number of these occurrences and provide a point of information integration for a variety of medical industry contributors, specifically practitioners, nursing staff, medication administrators and hospital management.

While there is an overt benefit to enhanced technological efficiency in critical care, specifically as it relates to medical record retrieval and administering medication, there are also limitations that draw out the implementation process over an extended period of time. This can lead to unintended consequences based on the current chronic structure and process issues in isolation that occur in CCU on a daily basis, while eMAR is still in the integration process. The clinical care and hospital, industry is a 24 hour industry in what is arguably a global market. Another limitation to adapting to eMAR can be recognized in the vast amount of data currently in exchange between medical practitioners, which is all done through an information management system that must be restructured to function on eMAR supported resources. Hospitals have numerous clinical information systems including laboratory systems, pharmacy systems, radiology systems, and various others. The proposed Components of an Inpatient eMAR will include- Clinical documentation, computerized physician order entry, Clinical decision support, Electronic prescribing and electronic medication administration records, Electronic results reporting. However, Medication errors are the most frequent source of preventable medical errors in a hospital setting.

Medication administration record (MAR) is a log containing information about the order and documentation of administration of medication to the patient. Electronic Medication Administration Record (eMAR) is particularly useful for electronically track medication administration via bar coding to verify compliance with the five rights of medication administration for the right patient, proper medication, proper dose at right time and the right route. There are also controversial issues surrounding the concept of this type of technology used in collaboration with eMAR, such as the infringement of civil liberties imposed by accessing medical history through digital bar codes.

Implementing eMAR across the board as a resource for all CCU data management systems requires more than just technology; it requires the willingness of medical practitioners to adapt to change, and the foresight of Tort legislation to withstand the unintended impact of learning curve errors within the medical community. Ultimately, it is in the best interest of the medical industry as a whole to make the transition to eMAR. After assessing numerous medical cases of CCUs in their process of adapting to eMAR based protocols, it is found that through the use of technology to streamline the process, integrate complex tasks, and provide medication safety teams with real-time data, the benefits of eMAR can be enhanced and the unintended consequences reduced enough to far outweigh alternatives to applying an electronic medical record system.

Section A: Problem Identification

Identification of Problem and Issues

In evaluating the place eMAR implementation plays in improving inefficient medical operations in ICUs, there are two types of problems worth recognition. The initial problem deals with the deficiency in the medical industry, which eMAR seeks to resolve, specifically the medication errors that occur through transcription, or written medical records exchanges, across diverse medical units each with their own respective standards and protocol. The other problem directly relates to the eMAR implementation process and the obstacles that impede it from being realized. While there are numerous sub-issues that contribute, the main problem eMAR faces is the indecisiveness of hospital management initiate the adaption process. Electronic medical records are currently not the standard because in addition to There is also a learning curve factor that accompanies eMAR implementation that results in veteran nurses having difficulty unlearning old protocols as they relate to utilizing traditional medical record format verses electronic medication administration records. While studies show this learning curve is ultimately overcome after three months of complete implementation, the problem is that with intensive care units, three months can result in an increase in medical errors that could be crippling to hospital sustainability.

It is felt that a continuous quality improvement approach is required primarily on bar-code implementation at hospital critical care units and acute wards. As Poon and authors note, “Serious medication errors are common in hospitals and often occur during order transcription or administration of medication. To help prevent such errors, technology has been developed to verify medications by incorporating bar-code verification technology within an electronic medication-administration system (bar-code eMAR) (Poon et al, 2010).” Through eMAR use, nurses and medical practitioners can be better equipped to handle intensive care unit emergencies.

The most prevalent obstacle impeding the implementation of eMAR today is the learning curve and transitional errors that occur during the implementation process. Fear of the unknown, making mistakes, or perhaps not being able to adapt to the new technology, can results in nurses being reluctant to recognize it as a viable resource. Similar negative consequences have been documented in the context of essential practice before nurses of bar coding medication administration technology and smart intravenous pump technology. Much research with a longitudinal design is required to more recognize how EHR-related predictors of technology acceptance may change over time. This would help implementers of EHR technology identify serious problems that require being mention in the short- versus long term (Mooney, Boyle, Carayon, Cartmill, Blosky, Brown, R., Hackenberg, 2011).

Nursing staff at the intensive care unit spearheaded an endeavour to execute daily rounds based on undeniable changes in combined multidisciplinary team communication and patient results at hospital intensive care units. Medical details and hospital measures are going online, varying the way nurses and other health professionals do their works. When the Cleveland Clinic Department of Nursing Informatics executed an electronic medication administration record (eMAR) method to develop efficiency and patient safety, the team wanted to know if nurses using the method were pleased (Poon, Keohane, Yoon, Ditmore, Bane, Levtzion-Korach, & Moniz, 2010).

Available Solution of Problem and Issues

Over 15 years ago, information technology in the medical industry was recognized as an effective way to reduce the occurrence of medical errors. The problem, as William R. Hersh notes, was few hospitals took advantage of these resources. In his study “The Electronic Medical Record: Promises and Problems,” he supports the theory that a major obstacle for eMAR adaptation is overcoming the familiarity the medical industry has with the status quo. He notes that, “Despite the growth of computer technology in medicine, most medical encounters are still documented on paper medical records. The electronic medical record has numerous documented benefits, yet its use is still sparse (Hersh, 1995).” While this study was taken in 1995 it is till reflective of the current state of the medical industry. Karen M. Hunter provides further support for the idea that nothing much has changed and eMAR is effective in reducing medical errors, but still lacks implementation initiatives. In her study published in 2011, “Implementation of an Electronic Medication Administration Record and Bedside Verification System,” she notes that, “Due to staffing shortages and the expectations placed on staff today, human errors are becoming more prevalent in the administration of medications… Information technology has been shown to decrease medication errors… The percentage of the decrease of errors related to bar-coding ranges from 60 to 97% (Medical News Today, 2008, Patel 2009, Figge, 2009). Unfortunately, only 10 to 12% of hospitals have bar-coding in place (Hunter, 2011).” Hunter shows how even 15 years after the study done by Hersh, only 12% of hospitals take advantage of this technology. This is proof that eMAR implementation is an important issue to solve, because otherwise there is no foreseeable reason to assume it will resolve itself.

The implementation and use of EHR technology have raised numerous challenges, including end-user acceptance. In complex healthcare environments such as ICUs, it is necessary to understand end-user perceptions of the usability, usefulness, and acceptance of the technology. Most research on EHR acceptance has focused on physicians less is known about nurses and their acceptance of EHR technology and its different uses. Most challenges hospitals face occur during the temporary transition period between initial implementation and complete adaptation. There are also unique pitfalls to EHR use that can only be assessed after extended use of the technology. Carayon identifies this as the main reason why examining EHR performance should be done over multiple time-frames (Carayon, Cartmill, Blosky, Brown, Hackenberg, Hoonakker, Hundt, Norfolk, Wetterneck, & Walker, 2011).

Systematic assessment of the eMAR implementation process and performance is a intuitive solution to identifying problems early on, as well as better understanding the limitations of the of current resources.

A variety of different bar-code formats are in development and reading the newer formats require periodically updated scanning equipment. Decisions also were made about scanning procedures for certain products. For Example, bulk items, such as topical medications and inhalers and floor stock items, such as heparin flushes (Phillips, and Fleming, 2009).

Project objective

This proposal aims to adaptation and implementation of eMAR in the critical care unit. This proposal expands the workflow of nursing with particular details on the processes and them addressing a problems and issues in the professional work setting on adaptation and implementation of eMAR in the critical care unitTo measure intensive care unit (ICU) nurses taking of Electronic Health Records (EHR) technology and observe the relationship amongst EHR design, enactment factors, and nurse approval, the aim of this study is to increase and analysis a system for assessing effort of nursing and workflow during the process of medication administration.

Proposed solution

The solution to implementing eMAR as a standard requires the progressive implementation of medical tools and resources that can are bilaterally compatible, or functional, with both written and electronic records. Ultimately, results show eMAR significantly reduces medication errors, outside of the prolonged period of time in which it’s being adapted. This means a gradual transition of incorporating new technologies that are comprehensive of veteran methods will allow for a shorter adaption time for eMAR implementation. If done correctly, the transition could be virtually seamless.

A detailed understanding of the scale of nurse’s workflow in the inpatient surroundings is extremely beneficial to the successful addition of any bedside technology. Now the technology is gradually used at the bedside of the patients adding to more transparency and organized care.. Even though bedside technology such as bar coding has the possibility to develop medication safety, it can also have a significant impact on the workflow of nursing. For example, when technology of bar code causes nurses to take distance to administer medications, this could switch nurses from other pertinent patient-care activities that can have a related cause to decreasing staff ratios for nurses and result in poorer patient results (DeYoung, Vanderkooi and Barletta, 2009).

Besides, the need of enough time to administer medications can support nurses to bypass the bar code scanning action and significantly reduce the planned impact of this technology on patient safety. In the planning stages of developing the hospital’s bar code or electronic medication administration documentation (bar code or eMAR) method, nurses raised their worry about increasing the time spent on administering medications and reducing the time with patients.

Objective data are requiring about the relative sum of time worn out on the various roles that nurses are needed to complete. So, it is required to decide to perform a baseline evaluation of nurse workflow to notify the improvement of eMAR method.

How Proposed Innovation Addresses the Problem or Concern Identified.

The proposed innovation, of first implementing compatible technology that coincides with eMAR data addresses the problem of prolonged eMAR adaption in two ways. “A survey showed the 61% of Americans were “very concerned” about being given the wrong medicine. (Cohen, 1999) This shows that lay people are becoming more aware of medication errors through personal experience and through various media coverage (Hunter, 2011) ” First, nurses and medical practitioners apprehensive to eMAR use can be exposed to it indirectly through other devices with which they are already familiar; and second, by narrowing the comprehension gap for veteran nurses who have trouble adjusting to new ICU protocols, the problem of extended eMAR implementation time is also resolved and reduced to a more sustainable measure less likely to result in the backlash of unreasonable medical errors.

Section B: Solution Description

Brief description of proposed solution

Incorporating the use of technology that is dually functional with both written and electronic medical records reduces the transition time between implementing eMAR and utilizing it as an established protocol. Past studies demonstrate that the urgency of hospital care, specifically that posed by the demands of critical care units. Nursing Informatics need to work closely with nursing managers and staff nurses during the planning and implementation process, it took many years. It is always expected that, there will be some resistance to the new system. However many nurses might be excited about it. It is also expected that, the eMAR system will be used by all inpatient units at the main hospital campus along with the regional / branch hospitals. In the old system, a physician write the medication order, a hospital unit coordinator transcribe the order onto a medication administration record (MAR), and a nurse review the order for accuracy and faxed the order to the pharmacy where it is filled and need to send to the unit. Nurses then record the medication administration on the MAR. Today, physicians enter medication orders directly into an order entry system that is integrated with the eMAR system. The order is automatically will send to the pharmacy. The pharmacist verifies the order and sends a notification to the nurse, who ensures the order is accurate and later documents the administration on an electronic record.

Consistency of Proposed Solution with Current Research Knowledge

Current research knowledge on eMAR implementation suggests that no matter how beneficial eMAR implementation is at reducing medical errors, there is no reason to assume eMAR will be gradually implemented as the technology and research validating its benefits have been a matter of record for decades with no significant increase in hospital implementation. The proposal solutions assumes the current research to be correct, and intuitive to imply there will be no increase in eMAR implementation in hospitals without a drastic and radical change in medical industry protocol across the board. This is especially true as it relates to ICUs.

In general, satisfaction with eMAR on all themes studied improved significantly over time, except that eMAR is expected to enhance nurse/pharmacy communication. As noted in DeYoung Vanderkooi, and Barletta’s study, A total of 1465 medication administrations were observed 775 pre-implementation and 690 post-implementation for 92 patients, 45 preimplementation and 47 post-implementation. The medication error rate was reduced by 56% after the implementation of BCMA (19.7% versus 8.7% were less than 0.001). This benefit was related to a reduction associated with errors of wrong administration time. Wrong administration time errors decreased from 18.8% during pre-implementation to 7.5% postimplementation (p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in other error types. (DeYoung, Vanderkooi, & Barletta, 2009).

Consistency of Proposed Solution with Current Research Knowledge is also the key focus area. Lack of improvement in nurse/pharmacy communication may be a reflection of broader communication needs beyond eMAR and also, the time it takes to receive a medication once an order is placed. Similar to the study done by DeYoung and authors, Poon and authors also reported similar results in their study on Effect of bar-code technology on the safety of medication administration. The authors note that they conducted a “before-and-after, quasi-experimental study in an academic medical center that was implementing the bar-code eMAR. We assessed rates of errors in order transcription and medication administration on units before and after implementation of the bar-code eMAR (Poon, Keohane, Yoon, Ditmore, Bane, Levtzion-Korach, Moniz, Rotchschild, Kachalia, Hayes, Churchill,Lipsitz, Whittemore, Bates, Gandhi, & 2010).” They observed 14041 medication administrations and they reviewed 3082 order transcriptions. The end results supported the finding that, “Use of the bar-code eMAR substantially reduced the rate of errors in order transcription and in medication administration as well as potential adverse drug events (Poon, Keohane, Yoon, Ditmore, Bane, Levtzion-Korach, Moniz, Rotchschild, Kachalia, Hayes, Churchill,Lipsitz, Whittemore, Bates, Gandhi, & 2010).” While the study did not show eMAR was capable of completely eliminating medication errors, it did further support the consistent finding that eMAR is an overall better protocol than pervious standards.

Feasibility of Proposed Solution

Incorporating the use of progressive technologies that are usable with traditional record keeping methods but ultimately lead-in supplements to eMAR use is a subtle conservative route to adapting to the new wave technology across the board for a wide range of ICUs. In analysis, researchers learned that nurses with more experience and those who were less comfortable with computers were less satisfied with eMAR. However, nurses have come to appreciate the electronic medication administration system. They no longer get complaints. They hear comments like ‘how did they live without this’ and ‘don’t take it away. Researchers go on to note that, “Conclusion. The implementation of BCMA significantly reduced the number of wrong administration time errors in an adult medical ICU (DeYoung, Vanderkooi, & Barletta, 2009).” Thus it is expected the solution on adaptation and implementation of eMAR in the critical care unit seems practical and feasible.

- Discuss the way(s) in which the proposed solution is consistent with organization or community culture and resources.

Past research demonstrate that there are limitations within the medical industry preventing it from successfully enduring a complete implementation of eMAR and the technologies that accompany them without leaving the medical industry open to a significant increase in medical errors during the transition. Medical culture involves the prescriptions writing on a global scale .The culture of medication is one where a diverse array of symptoms can imply an even wider range of illnesses. An acute diagnosis of one medical practitioner can differ from that of another; both professionals could prescribe medication that can effectively treat their patient, but if mixed could do more damage than good. The use of eMAR is actually more consistent with the globalized nature of medical culture than current methods, as eMAR better allows for a centralized medical record system.

Section C: Research Support

Research base for the proposed solution

Research Reports

- Immediate Benefits Realized Following Implementation of Physician Order Entry at an Academic Medical Center:

- Bar code tech and emar significantly reduce medication errors:

- Effect of bar-code technology on the safety of medication administration

- Technology implementation and workarounds in the nursing home

- Quantifying Nursing Workflow in Medication Administration.

- “ICU Nurses’ Acceptance of Electronic Health Records.”

Acceptable internal and external validity

The acceptable internal and external validity for these reports relies on their application to the medical industry as a whole verses their application to specific departments like ICU, or on a broader scale markets outside of the medical industry. These studies are both externally and internally valid, because externally their findings are consistent with the popular concept that cloud computing, and centralized systems are more efficient. This concept is based on the notion that information will be more efficient and effective if it’s all universally connected through one global database. In addition to studies like (2), and study (3) which demonstrate that eMAR implementation reduces medication errors, there are studies like (4), (5) (6) and (1) that give a deeper look into the procedures and performance measurements of nursing, and how these measurements are effected through eMAR implementation. Likewise, the studies use controlled research specific to its sector to extract data that is credible, valid and relevant. The execution of a quality monitoring program that recognizes and corrects issues connected with using a Bar Code Assisted Medication Administration or abbreviated as BCMA system. The project scale concerned the growth of a pharmacy stationed quality program for component does a container in addition to bar code labelling to increase the scanning achievement rate of bars coded medications at the care point (Mims, Tucker, Carlson, Schneider and Bagby, 2009). Data is gathered from facility based BCMA coordinators at each medical centre regarding particular reasons for scanning circumvention of bedside, as well as victorious scan rates in the pharmacy and also at the bedside. The work group created strategies to ease issues in all areas. It is required to create a directive that described the best ways for unit dose packaging and labelling, as well as needs for in progress data collection and reporting. A quality monitoring program that recognized and given best-practice suggestions rectified issues connected with using a BCMA method and improved bar code labelling procedures (Mims, Tucker, Carlson, Schneider and Bagby, 2009).

Evaluation and scientific merit

- Immediate Benefits Realized Following Implementation of Physician Order Entry at an Academic Medical Center: Measurements:Comparisons were made pre- and post- Physician Order Entry (POE) for electronic system implementation. The time intervals between initiation and completion of pharmacy electronic order implementation was 3 months, the same as the amount of time leading into the implementation. Number of orders for: MRI (pre-POE, n=46; post-POE, n=70), radiology (pre-POE, n=11; post-POE,n=54), and laboratory orders (without POE, n=683; with POE, n=1,142); timeliness of countersignature of verbal order (University Hospitals [OSUH]: pre-POE, n=605; post-POE, n=19,225; James Cancer Hospital (James): pre-POE, n=478; post-POE, n=10,771); volume of nursing transcription errors (POE with manual MAR, n=888; POE with eMAR, n=396); length of stay and total cost (OSUH: pre-POE,n=8,228; post-POE, n=8,154; James: (pre-POE, n=6,471; post-POE, n=6,045). Results: Statistically significant reductions were seen following the implementation of POE for medication turn-around times leading to a higher number of orders made. In addition, POE combined with eMAR eliminated all physician and nursing transcription errors. (Mekhjian, 2002)

- Bar code tech and emar significantly reduce medication errors: Measurements:“Researchers compared 6,723 medication administrations on patient units that did not have bar code eMAR and 7,318 medication administrations on patient units that did. Results: The implementation of bar coding linked to an eMAR was associated with a 41 percent reduction in non-timing administration errors and a 51 percent reduction in potential drug-related adverse events from these errors. (Miliard, 2010)

Effect of bar-code technology on the safety of medication administration: They observed 14041 medication administrations and they reviewed 3082 order transcriptions. The end results supported the finding that, “Use of the bar-code eMAR substantially reduced the rate of errors in order transcription and in medication administration as well as potential adverse drug events (Poon, Keohane, Yoon, Ditmore, Bane, Levtzion-Korach, Moniz, Rotchschild, Kachalia, Hayes, Churchill,Lipsitz, Whittemore, Bates, Gandhi, & 2010).” While the study did not show eMAR was capable of completely eliminating medication errors, it did further support the consistent finding that eMAR is an overall better protocol than pervious standards. (Poon, Keohane, Yoon, Ditmore, Bane, Levtzion-Korach, Moniz, Rotchschild, Kachalia, Hayes, Churchill,Lipsitz, Whittemore, Bates, Gandhi, & 2010).”

- Technology implementation and workarounds in the nursing home. “ResultsWorkarounds presented in two distinct patterns, those related to work flow blocks introduced by technology and those related to organizational processes not reengineered to effectively integrate with the technology. Workarounds such as safety alert overrides and shortcuts to documentation resulted from first-order problem solving of immediate blocks. Nursing home staff as individuals frequently used first-order problem solving instead of the more sophisticated second-order problem solving approach used by the medication safety team. (Vogelismeler, 2007). ”

- Quantifying Nursing Workflow in Medication Administration. To assess eMAR implementation learning curve times, the authors do a nurse workflow study to estimate the amount of time takes nurses to do various patient care activities. Methods: The distribution of time over different periods of nurse activities was measured through work sampling, self reporting on the behalf of nurse, or through continuous time motion observations. The study was performed on the inpatient units of a “735-bed tertiary academic medical center over a 6-month period. While no patient information was collected nurses’ general demographic information was collected and then de-identified (Keohane Bane, Featherstone Hayes, Woolf, Bates, Gandhi & Poon, 2008).

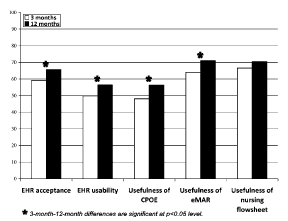

- “ICU Nurses’ Acceptance of Electronic Health Records.” In the past years hospitals, have been able to use technology to decrease medication mistakes. Since then, eMAR is the new wave of those technologies and has a proven record of earning the same results, if not better. This case information explains a difficulty to, and facilitators of, the execution of a pharmacy bar code scanning method to decrease medication provision mistakes at a leading academic medical centre. During the implementation nearly ten pharmacy staff was interviewed about their experiences. Interview observations are reviewed to recognize common subject (Carayon, Cartmill, Blosky, Brown, Hackenberg, Hoonakker, Hundt, Norfolk, Wetterneck, & Walker, 2011).On average, ICU nurses’ acceptance of the EHR technology was rather positive and improved over time. Their average perceptions of EHR usability and the usefulness of CPOE, eMAR, and nursing ?owsheets also improved over time. (Carayon, Cartmill, Blosky, Brown, Hackenberg, Hoonakker, Hundt, Norfolk, Wetterneck, & Walker, 2011).

(Carayon, Cartmill, Blosky, Brown, Hackenberg, Hoonakker, Hundt, Norfolk, Wetterneck, & Walker, 2011).

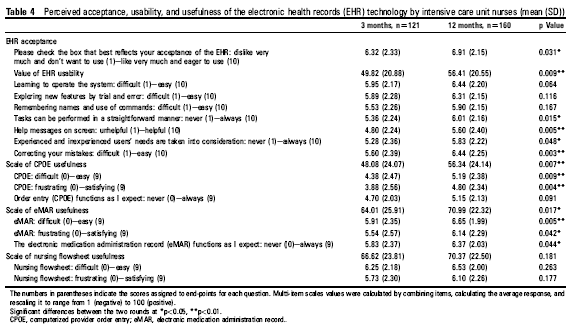

This table represents the perceived usefulness and usability of eMAR and EHR, bu nurses and other medical staff over the course of 3 months and then after 12.

(Carayon, Cartmill, Blosky, Brown, Hackenberg, Hoonakker, Hundt, Norfolk, Wetterneck, & Walker, 2011).

This table breaks down the eMAR performance rates over time as they relate to intensive care units. It compares results taken over the first 3 months and then those taken after 12 months. There is a noticeable difference between the two values with eMAR producing reduced error rates after 12 months and higher QI.

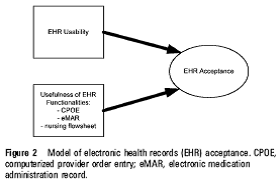

(Carayon, Cartmill, Blosky, Brown, Hackenberg, Hoonakker, Hundt, Norfolk, Wetterneck, & Walker, 2011).

This simple chart formed by Carayon illustrates the usefulness of eMAR. It is through its multiple functionalities across broad scales of the medical industry that make it EHR acceptable.

As nurse professionals think adopting bar code or eMAR systems, it is truly essential for organizations to identify the time spending by nurses so that new methods support nurse’s workflow and increase the time spent with the patients at the bedside. The research results by Keohane, Bane, Featherstone, Hayes, Woolf, Hurley, Bates, Gandhi, & Poon, 2008), signify that nurses spend the time about 25% on medication administration and 25% on speaking, highlighting the importance of these two processes, and it is also essential to notice that the medication administration activity happens all over the day and in equal scope on various kinds of units (Keohane, Bane, Featherstone, Hayes, Woolf, Hurley, Bates, Gandhi, & Poon, 2008).

Section C4- need to summarize main points of support for the proposed innovation based on the research studies.

The research studies mentioned all support the same argument that eMAR implementation is both a valued and effective technology for reducing medication errors in both ICUs and the hospital industry as a whole, but also that the fiscal cost of eMAR implementation was worth the effort. The Hunter research proves that without an effective action plan for implementation of eMAR, there is no reason to believe hospitals will gradually adapt to the alternative despite its benefits. All the reports yield data that suggests eMAR and cloud computing is better than paper medical documentation. These reports further support the proposed innovation of gradual implication through adapting to third party applications in that their conclusions are similar in recognizing reluctance by hospitals to implement the technology as a core obstacle to overcome. The proposed innovation seeks to overcome this obstacle.

Summaries

- Immediate Benefits Realized Following Implementation of Physician Order Entry at an Academic Medical Center: Summary: “A significant reduction in medication errors was seen following the implementation of POE for medication turn-around times. In addition, POE combined with eMAR eliminated all physician and nursing transcription errors (Mekhjian, 2002).” The specific benefit this suggests for Intensive Care Units is that through dual implementation of both POE and eMAR at the same time, complete reduction certain industry errors can be achieved. “Computerized POE offers complete and accurate information, automatic dose calculations, and clinical decision support at the point of care, including drug–drug interaction and allergy checking, as well as ordering supported by evidence-based best practice.” Methods and Results: Metrics to measure the tangible benefits of POE implementation was designed by the Ohio State University Health System (OSUHS). The core metrics measured through this system were patient care quality, safety, work flow efficiency, cost, and regulatory compliance. The OSUH formally collected data to review patient care practices, based on a collaboration of POE and eMAR implementation, direct observations of written orders prepared by physicians. In cases of inpatient care units where POE is implemented, all orders are processed through the system, with 80 percent being entered by physicians and the rest by nursing or other licensed care providers. Method 1: Time and Motion Study– This study was designed to asses medication turn-around times. Trained observers shadowed physicians and measured elements likes, time spent on rounds, the specific time of orders being written, and times orders were communicated to ancillary service areas like pharmacy and radiology. Experimenter bias was eliminated by utilizing allied health personnel for the collection of data. These outside members were not involved in the design and analysis study so they were free from internal bias. Method 2: Comparison of Data Between Areas with Differential Implementation of Electronic Systems- All areas selected for this study were comparable in terms of patient population and acuity. Surgical and medical intensive care units were specifically selected for this study. The POE/eMAR collaboration was implemented for surgical intensive care units (SICU), but not medical intensive care units (MICU). All Laboratory orders between July and August 2000 were included in this comparison study. Medication and transcription error comparison study with and without eMAR implementation between December 2000 and January 2000 was carried out as well using the same method. Method 3: Retrospective Review of Data- Pre-POE and post POE data is collected through a retrospective review of past patient records. The medical information Management staff provides past patient records that are assessed in comparison to the survey data from the prior studies. Results: Laboratory Result Turn-around time From July to August 2000, the SICU had 1,142 laboratory orders and the MICU 683 laboratory orders. From area A (POE and eMAR), 396 medication orders originating from 25 patients were analyzed and were compared with 888 medication orders from 80 patients in area B (POE and manual MAR). Retrospective Review of Data Order Requiring Physician Countersignature, studied before POE implementation, 605 patient orders were analyzed for OSUH, and 478 were analyzed for the James.

- Bar code tech and emar significantly reduce medication errors: Summary: After comparing 6,723 medication administrations with patients who did not utilize bar code eMAR with 7,318 medication administrations with patient that did, it was found that bar code use linked to an eMAR was associated with a 41% reduction in non-timing administration errors and a 51% reduction in potential drug-related adverse events from these errors (Miliard, 2010).

- Effect of bar-code technology on the safety of medication administration: Summary: 14,041 medication administrations were observed, as well as 3,082 order transcriptions. The study results in finding further support for bar-code eMAR implementation through a significant amount of reduced error ratesin order transcription and in medication administration. It is also found that there are less adverse drug reactions on the part of patients. as well as potential adverse drug events The study does not show eMAR was capable of completely eliminating medication errors, but it did imply that eMAR is an overall better protocol than pervious standards.

- Technology implementation and workarounds in the nursing home. Summary: This study assesses protocol for dealing with errors that might occur with the technology during implementation, solutions referred to as workarounds presented in two distinct patterns, those related to work flow blocks introduced by technology and those related to organizational processes. Those related to the organizational process are not reengineered to effectively integrate with the technology. This study is most effective at supporting the use of this papers proposed innovation strategy. Workarounds such as safety alert overrides and shortcuts to documentation resulted from first-order problem solving of immediate blocks, instead of the more sophisticated second-order problem solving approach used by the medication safety team. (Vogelismeler, 2007).” Study Sample: As a part of a larger study, this qualitative evaluation was conducted to identify workarounds associated with the implementation of an electronic medication administration record. Measurements Open and axial coding techniques were used to validate and categorize types of workarounds in relation to work flow blocks. Methods: Data was collected using multi-methods including direct observation, process mapping, key informant interviews, and review of field notes from medication safety team meetings. Findings: Workarounds presented in two distinct patterns, those related to work flow blocks introduced by technology and those related to organizational processes not reengineered to effectively integrate with the technology. Workarounds such as safety alert overrides and shortcuts to documentation resulted from first-order problem solving of immediate blocks. Nursing home staff as individuals frequently used first-order problem solving instead of the more sophisticated second-order problem solving approach used by the medication safety team. Conclusion This study provides important practical examples of how nursing home staff work around work flow blocks encountered during the implementation of technology. Understanding these workarounds as a means of first-order problem solving is an important consideration to understanding risk to medication safety.

Quantifying Nursing Workflow in Medication Administration.

Summary: Findings from 116 two-hour observation periods

revealed that nurses spent 26.9% of their time on medication-related activities and 73.1% of their time on non-medication-related activities. Times remained relatively consistent across clinical areas, with the average time spent on medication-related activities ranging from 22.8% in the ICU setting to 29.1% in combined medical/surgery units. The proportion of time spent on medication-related versus non-medication-related activities was consistent throughout the day (Keohane Bane, Featherstone Hayes, Woolf, Bates, Gandhi & Poon, 2008).

- “ICU Nurses’ Acceptance of Electronic Health Records.” Summary: In this case study, facilitators are interviewed to assess the nurse acceptance and perceived usefulness and its effect on true implementation. Interview observations are reviewed and compared against one another. It’s found that ICU nurses’ acceptance of the EHR technology is positive and improves over time, specifically after 3 months. Their average perceptions of EHR usability and the usefulness of CPOE, eMAR, and nursing ?owsheets also improved over time. Study Sample: The authors analyzed data from two cross sectional survey questionnaires distributed to nurses working in four ICUs at a northeastern US regional medical center, 3 months and 12 months after HER implementation. Methods: Survey items were drawn from established instruments used to measure HER acceptance and usability, and the usefulness of three EHR functionalities, speci?cally computerized provider order entry (CPOE), the electronic medication administration record (eMAR), and a nursing documentation ?owsheet. Findings: On average, ICU nurses were more accepting of the EHR at 12 months as compared to 3 months. They also perceived the EHR as being more usable and both CPOE and eMAR as being more useful. Multivariate hierarchical modeling indicated that EHR usability and CPOE usefulness predicted EHR acceptance at both 3 and 12 months. At 3 months postimplementation, eMAR usefulness predicted EHR acceptance, but its effect disappeared at 12 months. Nursing ?owsheet usefulness predicted EHR acceptance but only at 12 months. Conclusion As the push toward implementation of EHR technology continues, more hospitals will face issues related to acceptance of EHR technology by staff caring for critically ill patients. This research suggests that factors related to technology design have strong effects on acceptance, even 1 year following the EHR implementation.

Section D: Implementation Plan

Overall Plan for Implementing the Proposed Solution

The plan of this study was to improve and analysis a method for assessing nursing attempt and workflow in the medication administration method. Every year, thousands of patients die from medication mistakes, and hospitals struggle for mistake reduction. As solution bar coding medication administration methods have been planned; though, many hospitals need the essential pre implementation workflow development data on medication administration processes to assess the present methods effectiveness.

The Hospital’s current Information Management (IM) Plan is already made and suggested significant changes and within its external environment warrant the development of a new IM Plan and a reassessment of how Hospital and its critical care unit will manage information over the next three to five years.

In order to assist Hospitals and their critical care units with creating an updated Information Management (IM) Plan, the scope of activities must include a current state summary of Hospital’s IM environment and recommendations for a three year IM Plan including:

- Updates to the IM vision;

- Recommendations for people (IM organization), process (IM operations) and technology (application and hardware) to support the Hospital’s operational objectives;

- Recommendations for an IM roadmap plan; and

- Immediate action summary / next steps.

The planning process consisted of a four phased approach: Initial Positioning, Review, Analyze and Create IM Plan. Key activities included interviews with senior management, focus groups with hospital stakeholders from various programs and departments, consultations with the Information Management Executive Committee (IMEC) and the Information Management Steering Committee (IMSC), data gathering and analysis, and development of key recommendations and a roadmap plan.

Methods for monitoring solution implementation

In order to describe the methods for monitoring solution implementation, it is expected that Nurse Professionals will be required averaged 15 minutes on each medication, and it is a risk of a break or interruption with every medication pass. System challenges faced by nurses at the time of medication administration process guide to threats to patient protection, work around, workflow inefficiencies, and interruptions during a time when concentration is most required to prevent a mistake (Elganzouri, Standish and Androwich, 2009).

The proposed Bar code technology for medication administration will focus on medication mistakes and nurse satisfaction. A barcode administration system gives a secure method for the delivery of medications during the entire method, but reasons that negatively affect nurse contentment need to be notified.

Proposed theory of planned change

The established theory of planned change that most accordingly flows with the proposed innovation is Kurt Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory, “According to Lewin, the first step in the process of changing behavior is to unfreeze the existing situation or status quo. The status quo is considered the equilibrium state. Unfreezing is necessary to overcome the strains of individual resistance and group conformity (1951).” The three main steps of this process involve halting the current strategies, then gradually implementing the transitional impetus for change. In the case of the proposed innovation, this means incorporating the use of third party resources compatible with eMAR.

It is expected to describe the ways in which a hypothesis of planned change was used to improve the execution plan for adaptation and implementation of eMAR in the critical care unit. To support this American Society of Health-System Pharmacist (ASHP) survey may be referred, where ASHP national survey of pharmacy exercise in a hospital environment: Dispensing and administration reason. Outcomes of the 2008 ASHP national survey of pharmacy run-through in a hospital environment that relate to distributing, and administrations are obtainable (Pedersen, Schneider and Scheckelhoff, 2008).

In most of the hospitals safe systems continue to be in position, but the taking up of new technology is quickly changing the rationalism of medication allocation. Pharmacists are persistent to develop medication exercise at the dispensing as well as management steps of the medicine made use of method (Pedersen, Schneider and Scheckelhoff, 2008).

AHRQ report describes how bar coding medication enhances protection and quality. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Resource Centre for Health Information Technology has given a report that explains how barcode medication administration can develop the quality, safety, competence and effectiveness of healthcare. The report concentrates on course learned from AHRQ projects by the usage of barcode medication administration and technologies of electronic medication administration record (eMAR). According to the AHRQ, medication mistakes are the most common reason of poor medical events. The Institute of Medicine has approximated that more than million people in injuries and nearly 100,000 deaths can be happened due to medical mistakes every year. Adverse drug proceedings are approximated to cost the industry $2 billion a year (Pedersen, Schneider and Scheckelhoff, 2008; Sorra and Dyer, 2010).

Feasibility of the implementation plan

On the basis of the plan for implementing the proposed solution there already identify resources needed of the proposed solution’s implementation along with the methods for monitoring solution implementation. This describes the ways in which an assumption of planned transformation was used to enhance the execution plan is more realistic, viable and feasible.

It is virtually impossible to place a specific fiscal cost to eMAR implementation, since there is such a wide range of budgetary considerations and the ultimate cost depends on the nature of the vendor. Budgetary considerations can be isolated to put assessing the actual cost into a more understandable perspective. The following are some costs that will arise during the process of implementing this plan.

eMAR Budgetary Considerations

- Pre-Implementation Costs

- Connectivity

- Data Security

- Actual Cost of System

- Ongoing Maintenance and Technical Support

- Training

- Conversion from Paper

- Future Uses

Other Budget Considerations

Corporate Budget

- Infrastructure upgrades

- Mobile carts for computers (laptops and scanners)

- Thermal printers for pharmacy

- Meditech software upgrades

Facility Budget

- Operational costs for bar coding medications

- Fixtures or changes to pharmacy

- Staff time for planning, testing, developing, training

- Printers for armbands

- Travel for site visits

Resources needed of the proposed solution’s implementation

In order to support adaptation and implementation of eMAR in the critical care unit, it is expected that team of 5 core technology consultant, and tech support is required along with the 2 trainers who can demonstrate and train the nurses. It is assumed that, suggested significant changes and within its external environment warrant the development of a new IM Plan and a reassessment of how Hospital and its critical care unit will manage information over the next three to five years will be take place. Supplemental organization methods such as flowcharting must be implemented to decrease inefficiency as noted by Hunter, “Flowcharting the new process shows what changes need to be made. Flowcharting will help teams to understand all steps in the process by serving to identify inefficiency, misunderstandings, redundancies and areas of neglect while providing insights into how a process should be performed. (Hunter, 2011) ”

Action Plan

Assuming the appropriate resources are allocated, the following activities should be completed over the next 18 months to ensure that the IM Plan is properly communicated and executed.

| Timeframe | Activities |

| First 100 days | Obtain feedback from key stakeholders on the IM plan. |

| Evaluate and update the IM governance structure. | |

| Complete the 3 year roadmap. The prerequisites include:

1. Develop a project prioritization framework. 2. Develop a sustainable funding model. 3. Identify the human resources required to sustain operations and upcoming IM initiatives. |

|

| Finalize the IM Plan. | |

| Next 3 to 6 months | Develop a strategy that identifies and plans for the interdependencies of external IM initiatives and partnerships. |

| Communicate the IM plan to stakeholders. | |

| Establish a formal project management methodology. | |

| Define the 3 year EHR strategy. The prerequisite includes developing a strategy for bridging clinical areas and IM. | |

| Establish a formal change management process. | |

| Next 7 to 12 months | Develop a process for conducting a progress review of the IM plan. |

| Consider external funding opportunities. | |

| Continue the implementation of the EHR strategy. | |

| Subsequent 13 to 18 months | Develop a strategy for improving the data collection quality and decision support reporting tools. |

| Develop a strategy to engage users in the review of systems to improve functionality and sharing of information. |

Section E: Evaluation Plan

Outcome Measure

The result of bar code medication administration or BCMA on the proportion of medication errors in adult cases in a medical intensive care unit will be considered.

Main Outcome Measures: Assessment of developed attitudes and technical performance responses to the new system, as well as changes to delivery of care and work practices.

Medication mistakes would recognized in a community training hospital medical ICU using a straight observation method whereby nurses are realized administering medications.

Validity

These evaluations tend to produce valued and credible results that enforce the validity of both their processes and the measures being evaluated. In previous Evaluations measuring the success outcomes of eMAR implementation, It is expected that, Observations happened for four consecutive 24-hour terms one month before in addition to four months after the execution of BCMA. Mistakes in the following types were recorded: incorrect drug, incorrect administration time, incorrect route, wrong dose, exclusion, administration of a drug without proper order, and documentation mistake. Two evaluators evaluated all mistakes for exactness. The primary measure is the amount of time that nurses spent on medication administration associated activities. Secondary measure included the amount of time spent given for patient care and engaging in inefficient activities.

A well-designed BCMA method does not raise the amount of time that the nurses used up on medication administration actions. Barcode medication administration technology possible streamlined activities for nurses, permitting them more time for other professional activities. The results should assist to relieve concerns regarding the impact of BCMA on the workflow of nursing (Poon, Keohane, Bane, Featherstone, Hays, Dervan, Woolf, Hayes, Newmark, Gandhi, 2008).

How reliable is this technology?

Research demonstrates that not only is the technology effective and efficient but it’s reliability can be measured through the comparison results found in data where eMAR is pitted against paper documentation, or transcription. In all case studies eMAR results in lower medication error rates. Despite this fact, there are no guarantees technology will always function properly, in which same the protocols standard for counteracting a cyber-terrorist attack, or an electrical power outage, must be put in place.

Sensitivity to change:

The purpose of the initiative is to create an environment for a gradual transition from paper documentation to electronic. This means the main focus is to eliminate sensitivity to change through the integration of more third party tools compatible with both methods the old and the new. In terms of sensitivity to change in the near future when the technology of this new innovation initiative is no longer cutting edge. Rationale suggests that this same method of gradual integration can be readapted to appropriate change.

Appropriateness of the outcome measure.

The Outcome measure of : Assessment of technical performance, developed attitudes to the new system, changes to delivery of care and work practices, is appropriate for this project because it satisfies all the core expectations held by internal and external stakeholders.

Evaluation Data collection

Collecting data, specifically as it relate to outcome measures and evaluations, will be handles through surveys administered to nurses and other hospital staff. The results of these survey will then be evaluated and peer reviewed. A thesis assessment of the current status of eMAR implementation will be formulated based on the data.

Rationale for using those methods:

Surveys as a form of data retrieval is one of the most used and respected methods imaginable for this type of undertaking. Specifically in the case of on-staff nurses working intensive care units, their responses will result in more valued results

Time, fiscal, and personnel resources needed for evaluation.

Team management tools, and schedule management tools, as well as a specific budget set aside, just for the evaluation staff is mandatory for the success of the evaluation process. A staff has to established specifically for the process of evaluating the accomplishment of outcome measures. Also the evaluation process must span from the time of implementation to 3-12 months after its use. These evaluations should be carried out every 3-6 months.

Feasibility of the Evaluation Plan in the Work Setting:

The evaluation method involves delivering surveys to nurses in the mail. For example, if 3,000 to 5,000 surveys are delivered to on-staff hospital nurses who work at hospitals throughout the country currently implementing eMAR, then it can be expected at least 1/5th of the applicant pool will complete the surveys and return their responses. This is a large enough study group to get valued responses. Likwise, nurses on staff at critical care units are most exposed on a daily basis to eMAR performance

Critical Success Factors

In order to ensure success and sustainment of the IM Plan, the following critical success factors should be implemented and put into place before any of the other recommendations:

- IM Leadership and Governance

Senior management needs to be more engaged in providing leadership and direction on IM initiatives. The successful implementation of an IM plan is dependent upon a clearly articulated governance structure that clarifies decision making and provides credible leadership. An organizational assessment should be conducted to review roles, leadership, competencies, etc.

- Project Prioritization and Project Management

All IM projects will follow a standard and transparent project prioritization process to ensure that mission critical projects are prioritized and have dedicated resources to support them. A formal project management methodology will be followed for all projects. Supporting tools may include a Project Charter, Project Plan, Status Reports, Issue and Risk Management Logs.

- Sustainable Funding and Resources

Each project will require the allocation of sustained and committed funding and human resources (IS, clinical, and management) that will enable a successful delivery within the agreed upon schedule and budget.

- Change Management and Communications Process

A formal change management and communication process will need to be developed and should include stakeholder engagement, communication, training, education and process re-design. Individuals that will use the systems being implemented must be able to adopt them into their workflows and derive benefit from them.

Evaluation Data Collection

Evaluation data collection will describe the approaches for collecting consequence allocation data as well as the logic for using those approaches. It is also expected to identify resources needed for evaluation along with the feasibility of the evaluation plan.

Many hospitals utilize barcode medication administration (BCMA) technology to develop inpatient medication protection. Though, executions of this technology require urgent variances in workflow for nurses, possibly intrusive with the delivery of care to patients.

Section F: Decision Making

Specific plans

Decision-making is hugely significant because nurses are the only healthcare professionals whom they give exceptional care to many patients at the same time. Nurses with various skill levels will react differently to each situation, and the instruction of other nurses is another main aspect of the CNS role. Managers make sure the safe condition of care by paying concentration to the “specialist ratio” on the floor, otherwise known as “kind staffing.” Their planning helps to make sure that the correct skill blend is present in every patient. Prompt communication of data given by the patient gives a way of instant evaluation favour to all healthcare team members for planning and delivering care for the patient. Both students and experienced nurses who utilize the portal increase an understanding of procedure of data entered into the EMR is shared between regulations, transferring it from easy data entry to information and knowledge that improves patient care and safety (Poon, Keohane, Bane, Featherstone, Hays, Dervan, Woolf, Hayes, Newmark, Gandhi, 2008).

After consultations with the Hospital and its critical care unit stakeholders indicated that the existing IM vision needed refinement to reflect the organization’s view for the future of IM. Hospital’s new IM vision is:

Hospital and it’s critical care unit will support the delivery of quality health care and ensure patient safety through access to secure, accurate, relevant and timely information that is available at any time, from any location and is shared across the continuum of care.

Through the consultation process, the following IM directions emerged as priorities for IM at Hospital:

- Promote a high level of quality of care and patient safety through enhanced access to and the effective use of integrated information;

- Demonstrate strong commitment to accountability through the refinement of accurate and reliable reporting tools;

- Continue to facilitate processes to improve organizational effectiveness and efficiency, and enhance knowledge and learning, job satisfaction, and user adoption;

- Empower patients and improve the patient experience through enhanced access to health information allowing patients to make informed health care decisions; and

- Be on the leading edge of innovation and technology.

Expected Results

The preponderance of the medication management errors recognised by the BCMA system are judged to be benevolent; 1% of the mistakes reviewed are rated as having the possible to the outcome in an extreme or life intimidating adverse occasion, 8% are judged to have the possible to generate reasonable adverse effects. Medication mistakes due to an amount being administered when there is no corresponding order in the computer system is considerably more possible to produce reasonable or extreme results than other types of medication faults. Mistakes that involved medications chosen as high alert drugs are also more likely to create reasonable or severe difficult actions than non high alert drugs.

The majority of medication administration mistakes detected by a BCMA system are judged to be kind and pretence minimal safety risks; though, the numbers and severity of medication administration mistakes that happen even though the use of a BCMA system recommends that there are opportunities to develop these systems and how the information they create is used (Sakowski, Newman and Dozier, 2008; Lyons, Specht, Karlman, and Maas, 2008).

Thus, the expected result will focus on several issues, such as problem identification, time spent on professional work setting, and it gives an available solution of problems and issues, brief description of proposed solution and feasibility of proposed solution, and it gives the implementation, evaluation and decision making plans.

Key Observations

Overall, Hospital and its critical care unit have been adequately managing its IM operations given the human and financial resource constraints. The e-Health landscape has become increasingly dynamic over the past few years. E-Health is becoming an increasing priority in the national and provincial health care landscape; there are increasing demands for IM initiatives and reporting requirements from the hospital. As the demand for IM resources increases, Hospital and its critical care unit will require a solid foundation in place to manage, prioritize and balance the growing number of internal and external IM initiatives that arise.

As Hospital and its critical care unit takes on new initiatives, it will need to evaluate whether the initiatives will improve patient care and ensure that they align with the IM vision and IM directions. New initiatives may shift resources from current initiatives, which may inhibit the hospital from moving forward with critical initiatives such as the development of the Electronic Health Record (EHR).

The task at hand is to plan for the future and establish the foundation to effectively use IM to support the delivery of quality health care in a changing environment. The following is a brief description of the key observations for areas of improvement that were gathered through the stakeholder consultation process

| Key Observations*

(*based on stakeholder consultations’ feedback) |

|

| Strategy | Internal and External Partnerships: There are increasing opportunities for collaboration. The growing number of competing internal and external priorities is shifting the focus away from critical hospital projects and those that are at the operational level.

EHR Strategy: A comprehensive EHR strategy does not exist at Hospital. The Electronic Data and Documentation Integrated Everywhere (EDDIE) project, a major component of the EHR project at Hospital, was initiated several years ago. Hospital and its critical care unit have started the implementation of nursing clinical documentation. The overall EDDIE project has been delayed due to conflicting hospital priorities, identification of project prerequisites and limited resources with relevant experience. |

| Structure | IM Spending: Capital funds are dedicated to IM initiatives and resources, however, operational funds to sustain new initiatives are not consistently budgeted for. The number of internal and external IM initiatives is increasing, while the IM budget has decreased slightly over the past 2 years. Currently Hospital and it’s critical care unit spends 2.3% of its budget on Information Systems (IS) and Telecommunications, which is significantly lower than the ideal spending on IT in healthcare but is relatively consistent with the provincial and LHIN spending. |

| People | Clinical Informatics Expertise: Hospital and its critical care unit currently have limited formal clinical informatics expertise and leadership. The IS department has strong IT experience but limited clinical knowledge. The clinical staffs have limited IM project management experience.

Human Resources: There are limited human resources to support IM projects. IM staff, clinicians, and management are balancing between operational responsibilities and supporting new initiatives. |

| Process | IM Leadership and Governance: The accountability and decision making process of IM projects are unclear to staff. The level of senior leadership on IM projects is inconsistent.

IM Project Prioritization Process: An IM project prioritization process exists at Hospital; however, the process is not transparent, nor is it consistently followed by the hospital. Decision Support and Business Intelligence (BI) Tools: Investments in BI tools are continuously being made; however, clinical programs and hospital departments have raised the ability to extract relevant information for administrative decision making as a major issue. Project Management: Projects at Hospital and its critical care unit are not fully realized due to the lack of a project management structure, standard methodology, and adequate resources trained in project management. Change Management and Communications: Staff has indicated that they are not always aware of system changes. Communication of the benefits of system changes and the impact to the staff’s workflow are not consistently communicated and read by staff. Information Sharing: Staff indicated that there is limited flow of information between departments and between modules. |

| Technology | Clinical Systems Functionality and Usability: Clinicians have identified issues with the usability and standardization of clinical systems. There is duplicate and inconsistent collection of information. There is a limited enterprise architecture function within the hospital to oversee the strategy, architectural design and implementation of operational and business support systems. |

Key Recommendations

The following recommendations were shaped by the IM issues that were identified during the stakeholder consultation process.

| Key Recommendations | |

| Strategy | Develop a strategy that identifies and plans for the interdependencies of external IM initiatives and partnerships.

Hospital and its critical care unit should leverage external partnerships, while balancing external and internal priorities. Processes should be implemented to align internal IM initiatives with external initiatives, provincial e-Health policies and standards. Unexpected mandatory regional and provincial initiatives should also be planned and budgeted for (human and financial resources). |

| Define a clear and comprehensive EHR strategy and roadmap.

A clear and comprehensive three year EHR strategy is needed to guide Hospital and its critical care unit to an operational EHR. This strategy would include the accountability structure, goals, timelines, milestones, and a process for tracking progress. The budget for each EHR goal should be developed or re-evaluated to include the appropriate human and financial resources. |

|

| Structure | Develop a sustainable financial model.

The current financial model for IM should be evaluated to ensure that capital costs, operating costs and resources are adequately and consistently budgeted for. Hospital and its critical care unit should gather baseline metrics of IM costs and consider using an IT financial model such as Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) to identify not only the cost of purchase but also the use and maintenance of the IT equipment or system, which will include direct and indirect costs. |

| People | Develop a strategy for bridging clinical areas and IM.

Clinical informatics champions should be identified to act as liaisons between clinical areas and IM. Hospital and its critical care unit should identify and, or recruit clinical informatics leadership. In addition, the hospital should consider clinical informatics training sessions for interested clinicians to build interest and expertise in clinical informatics. |

| Invest in resources to sustain operations and to support upcoming IM internal and external initiatives.

One-time and ongoing resource requirements should be identified to support operations for all projects. Dedicated IS, clinical and management resources should be consistently identified for all IM projects. |

|

| Process | Evaluate and update the current IM governance structure and continue to engage senior management on IM initiatives.

The existing IM governance framework should be evaluated to include a clear IM decision making model, governance structure and processes. Policies, guiding principles and standards to support the governance structure will also need to be developed and, or evaluated. The roles and responsibilities of the IMSC and IMEC should be clarified. Key senior management should be identified and engaged to move projects forward. |

| Reform the IM project prioritization and decision making processes.

A formal project prioritization and gating process should be developed so that mission critical projects are identified and implemented. A formal structure to review projects should be developed, as well as a process to approve and review new projects. |

|

| Improve data collection quality and decision support reporting tools.

Hospital and its critical care unit should develop a process for quality control to ensure data extracted are accurate. Staff should be engaged in the implementation of BI tools, the design of reports and training on the utilization of BI tools. |

|

| Formalize the project management methodology and tracking processes.

Hospital and its critical care unit should develop a formal project management methodology and templates. This methodology should include a process for tracking milestones, identifying risks, independencies and lessons learned. An annual internal operation review of all IM projects should be planned for and conducted. |

|

| Formalize the change management and communication processes.

A standard change management guideline and communication process should be incorporated as part of the project management methodology. Existing clinical user groups should be utilized to enhance communication with the clinical programs. A process should be developed to engage selected end users in the design, implementation and testing of information systems. Hospital and its critical care unit may want to leverage relevant leading practices from Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL) and Information Technology Service Management (ITSM). |

|

| Increase the sharing of information across departments / modules in the system design process.

New systems development and changes should be brought to the IM Committees to assist in identifying interdependencies. When designing new modules, Hospital and its critical care unit should continue to involve stakeholders from multiple disciplines and departments to assist in identifying potential interdependencies between systems and departments. |

|

| Technology | Improve the functionality of current clinical systems.

The commitment and rational behind the strategic investment into Hospital should be communicated to Hospital and its critical care unit stakeholders. A process for standardizing the user interface and collection of data should be developed. Hospital should continue to use clinical user groups to enhance implementation of clinical standards and data entry. Hospital should develop an enterprise architecture strategy that oversees the architectural design, strategy and implementation of operational and business support systems. |

- Successful Project Solution

eMAR is a project solution. Research shows it’s effective at reducing medication errors and transcription errors alike, but are these results sustainable? How can one know for sure eMAR is not susceptible to vulnerabilities? Through supplementation and experimentation the use of eMAR as a viable medical resource is reinforced. Through engaging stakeholders about results and corresponding with them as well alerting community members about new advancements within the sector, knowledge can be external. Supplementing eMAR with the cloud technologies that support it and the third party software that already exist within ICU protocol, gives it more sustainability through valid integration. Collaborating with other medical resources reinforces the infrastructure backing it.

- Extending successful project solutions

This involves investing in resources to sustain operations that are effective. It also requires building a network of support. Stick with what works and document it. The ultimate goal of eMAR technology is to bridge the gap between the medical and IT, don’t just settle for this one implementation. Adapt to change. Sustain what is successful by cutting what isn’t and don’t workaround obstacles, work through them. Most importantly be honest about what is working.

- Specific plans to revise an unsuccessful project solution

Departmentalizing eMAR implementation has more benefits than just minimizing risk. A commonly used alternative method of terminating an unsuccessful solution is to modify it into a new one. Nurse transcription errors are eliminated completely when transcription is no longer the standard ICU protocol. Change the protocol to comprehensive of more than one solution and the unsuccessful solution is made into something new entirely. Utilize technology to make old methods new ones; innovate the standard system and give it new functionality.

- Specific plans to terminate an unsuccessful solution:

Staying the course is not always the best method. When implementing eMAR through the use of third party technologies, if project results are not producing expected returns (ie nurses are not adapting as expected, patients are not responding to medication as prescribed, or medication errors persist) change the routine. An example of this can be seen with the Mekhjian studies where eMAR was implemented aggressively over prolonged periods, halted during other spans and then collaborated with Physician order entries to ultimately reduce medication errors completely. Theories are only as valuable as the experimentation by which they are enforced. If implementation process is systematic, make it sporadic; if it’s gradual accelerate it. Maintain feedback and correspondence with stakeholders and never be hesitant to stop completely and start over.

- Plans For Feedback : The following are specific people on whom focus needs to be placed to maintain open path of communication to ensure the program’s success.

- Involved Staff

- Non-involved Staff

- Physicians

- Patients/Families

- Community

These are the main stakeholders involved in the eMAR implementation. Some are stakeholders regardless of any direct affiliation with the project or medical industry. For example, the community surrounding an ICU should necessarily be given the same amount of feedback as a patient, or family member of a patient, but some form of loose communication must be established during the implementation process as every member of the community is a potential patient. This form of loose communication can he handled through e-mail newsletter, or even public advertising to announce that there will be a systematic shift in hospital protocol.

Improvement Schedules

- Improve use of technology to prevent and detect error

- Use MAR from CPCS on all inpatient units

- Analysis of scan med report / measurement report

- Regional meetings

- MD Training

- Admin Training

- Beyond Blame video

- ISMP Self-Assessment

- HCA Patient Safety video

- Executive walk arounds

- eMAR monthly conference call

- eMAR Website

- eMAR monthly Newsletter

- eMAR and Barcoding Mailbox and Discussion Group

Through the above methods, continuous engagement with stakeholders is possible. Feedback both from medical staff and patients, as well as community members must be managed diligently to extract the most value from the eMAR transition and implementation in the briefest period possible. It is through constant feedback that the project can find ground on which to stand.

References

Carayon, P., Cartmill, R., Blosky, M.A., Brown, R., Hackenberg, M., Hoonakker, P., Hundt, A.S., Norfolk, E., Wetterneck, T.B. & Walker, J. (2011). “ICU Nurses’ Acceptance of Electronic Health Records.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 18 (6): 812-9.

DeYoung, J. L., Vanderkooi, M. E., & Barletta, J. F. (2009). Effect of bar-code-assisted medication administration on medication error rates in an adult medical intensive care unit. American journal of health system pharmacy AJHP official journal of the American Society of Health System Pharmacists, 66(12), 1110-1115.

Elganzouri, E. S., Standish, C. A., & Androwich, I. (2009). Medication Administration Time Study (MATS): nursing staff performance of medication administration. The Journal of nursing administration, 39(5), 204-210.

Hughes, R.G. (2008). Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ Publication

Hunter, K. (2011). Implementation of an Electronic Medication Administration Record and

Bedside Verification System. Online Journal of Nursing Informatics (OJNI), 15 (2), Available at http://ojni.org/issues/?p=672

Keohane, C. A., Bane, A. D., Featherstone, E., Hayes, J., Woolf, S., Hurley, A., Bates, D. W., Gandhi T.K., Poon, E.G. (2008). Quantifying nursing workflow in medication administration. The Journal of nursing administration, 38(1), 19-26.

Kritsonis, A. (2004). Comparison of change theories. Retrieved from http://nationalforum.com/Electronic Journal Volumes/Kritsonis, Alicia Comparison of Change Theories.pdf