Analysis of Funds of Funds, Thesis Paper Example

Abstract

In order to mitigate certain risks, to which hedge funds are often exposed, funds of funds bundles together a select group of hedge funds and invests in them collectively on the belief that over the long term it has a very high probability of making profit. A fund of hedge funds, or fund of funds, provides a way of getting exposure to a group of hedge funds creating a packaged instrument that has lower risk and less exposure to any single investor’s decision. This smoothes-out exposure to short term price movements, because there are certain risks that are difficult to quantify due to human error, volatile markets, or the fact that hedge funds are loosely regulated. The issue that arises with investing in funds of fund is additional concurred fees. On average, the funds of funds after-fee returns are lower than those posted by the standard hedge fund. An outsider looking in would deduce this means hedge funds offer a greater value. Fund of fund practitioners argue, the value of this investment model should not be assessed based on publicly reported hedge fund returns. Publicly reported data is subject to fund bias which does not account for many factors in the relationship between funds of funds and hedge funds. Through, keen asset allocation concepts, fund of fund benchmark distribution can allow for competitive after-fee returns. Most importantly this report concludes that the deciding factor certifying funds of funds as a preferred investment structure over hedge funds can be found in assessing funds of funds true benchmark, which ultimately decides relative hurdle rates. . This puts funds of funds in logical position to be recognized as a valued investment still deserving of their fees of fees.

Part 1

Comparing and Contrasting Funds of Funds and Hedge Funds

Introduction

The financial industry is a complex system that involves different elements consisting of volatile upswings and downswings. This is the reason why security measures imposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) exist. There is a considerable need to protect investor interests. While there are specific safeguards designed to ensure that invested assets are well secured and protected against fraud, risk will always be a part of investing. It is a natural precaution of investing to avoid fees as much as possible. In regards to trading securities, limiting brokerage fees and surcharges results in the trader being able to have a narrower discrepancy between entry and exit points. This allows them to be exposed to the market for briefer periods and still see profits, ultimately limiting their risk. In many ways the same is true when it comes to investing in hedge funds or funds of funds. In fact, the original reason why hedge funds were created in 1949 was to create an investment vehicle that would ‘hedge’ against risk by diversifying positions investors had in the market (Anson, 2006); But as the market has evolved, hedge funds have established a reputation as one of the most dangerous investment structures in investing, thus also making them potentially one of the most profitable. Funds of funds on the other hand, have made a space in this market by providing lower income investors market access where there once was none. Funds of funds also provide more diversity and security for investments. This is the reason why fund of funds have garnered much interest among savvy investors, and working for one is often likened to what working for a hedge fund was back in the mid 80’s to late 90’s. .

Hedge Funds

What are Hedge Funds?

A hedge fund is an aggressively managed portfolio of investments that use progressive strategies like leveraged, derivative, long, and short positions. They often invest in domestic and international markets with absolute profit as the goal, or high returns above a specific benchmark. Hedge funds are legally understood as private investment firms that are open to a select and limited number of investors. They tend to require significantly large initial minimum investments. Hedge funds are illiquid, which means they often require investors to keep their assets in the fund for at least one year. The term hedging actually defines the practice of reducing risk, but the goal of most hedge funds is to maximize return on investment through taking more risks. The historical relevance of the name stems from the first hedge funds tried to hedge against the downside risk of a bear market by shorting the market mutual funds generally can’t enter into short positions as one of their primary goals. Today, hedge funds use a wide range of strategies, making it false to identify hedge funds as only hedging risk. Hedge funds have more risk due to the tendency of managers to make speculative investments. These types of investments can be extremely volatile than the overall market.

Hedge Funds Verse Mutual Funds?

Mutual funds and hedge funds are both portfolios run by managers. A manager or group of managers select investments that they feel will perform well and then they group them into one collective portfolio. Shares of the fund are sold to investors who then can take part in the gains/losses of the holdings. The main advantage to investors is that they get instant diversification and professional management of their money.

Hedge funds are managed much more aggressively than their mutual fund counterparts. They are able to take speculative positions in derivative securities like options. They can also short-sell stocks, which increases leverage, and ultimately increases the risk. The main benefit of being able to short sell though is that the fund can still make profits even when the price falls. Highly leveraged positions like this are uncommon when it comes to mutual funds. This is also the reason why mutual funds are safer investments than hedge funds.

What is Short Selling?

Short selling is the act of making a market transaction where borrowed securities are sold in expectation of a price drop, and the seller is required to reimburse the purchase with the same exact number of shares they borrowed at some point in the future. The reason it’s called short selling is because it’s the opposite of taking a long position. A long position is one that expects the stock price to rise and makes money when this happens. A short position makes money if there is a decline in price.

Suppose an investor short sells 2,000 shares of a stock at $35 apiece and $70,000 is then put into that investor’s account. Let’s say the shares fall to $20 and the investor closes out the position. To close out the position, the investor will need to purchase 2,000 shares at $20 each ($40,000). The investor captures the difference between the amount that he or she receives from the short sale and the amount that was paid to close the position, or $30,000.

Short sellers are also required to follow margin rule requirements where 150% of the value of the shares shorted need to be in the traders account before the sale can be executed. If the value of the sale is $25,000 the margin requirement becomes $37,500. This is to ensure proceeds from the sale will be returned, by preventing another sale until the original share holder is reimbursed. Short selling is considered to be an advanced trading strategy, with unlimited potential losses. The way funds use leverage is by multiplying both gains and losses on monetary management through the point of borrowing (Ross, 1999). Through derivatives, or agreements on the payment that two separate parties are expected to provide each other within a specified time, investors are allowed to use up their assets to be borrowed by a fund manager who in turn would invest such amount into a program that would pay a particular profit within a specific time. When funds leverage, the process of borrowing is continuous; this means that the money is not consumed by the borrower, instead it’s passed on to other institutions to heighten its capacity to earn more.

How Hedge Funds Work

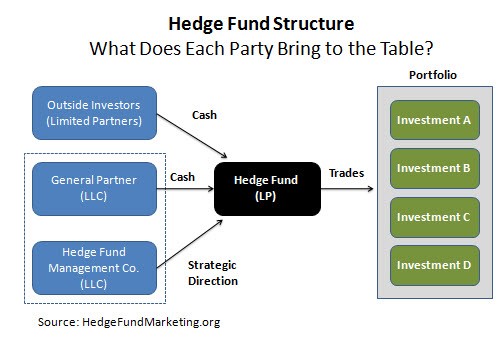

The diagram below demonstrates how a hedge fund is created: Notice that there are three the general partners, or primary contributors to the operation, the outside investors, and hedge fund management company.

Hedge funds are not open ended. They impose a lock in time period for investor funds, which is a span of time during which an investor can not withdraw their assets. The profits earned while investments are held within a hedge fund are not always transparent due to the fact that hedge funds are allowed to be secretive with most of their investment practices and do not have to regularly report to the SEC. Whether one is able to gain access to the progress of their investment outside of the scheduled report dates, is entirely up to the discretion of the hedge fund manager and the policies they must follow in regards to all other investors.

What Hedge Funds Offer

Overall, funds of funds have higher fees than hedge funds, because they charge the traditional hedge fund fees of all the underlying investments, in addition to the management fees of the fund of funds. These types of fees apply a significant limitation to overall returns. Hedge funds, on the other hand, are similar to mutual funds in that they pool investor money and invest it in a diverse number of investments. The main difference between hedge funds and mutual funds is that hedge funds are not required to register with the SEC. Positions within hedge funds don’t have to be publicly reported the way mutual fund holdings must be, and they are usually sold in private offerings. Hedge fund managers still have the same fiduciary responsibilities as registered investment advisors.

Because the SEC and other securities regulators have limited legal standing to perform routine checks on hedge fund activities, it makes it less likely Hedge fund managers won’t take-on extreme risk. Since funds of funds purchase numerous hedge funds (which themselves invest in a large number of volatile securities) the funds of funds ultimately own some of the same stocks or securities through several different funds. This actually reduces the diversification for which many investors seek funds of funds for in the first place, possibly negating the goal of the investment. On the other end, to protect the values of the hedge fund, investments that are withdrawn earlier than what has been agreed upon between the managers and their investors themselves are charged with a redemption or withdrawal fee. This option is established to reduce the chances by which investors withdraw their assets after a poor performance in the market. This would protect both the manager and the investor as they both try to make the agreement they have between each other work for the best benefits that each party could get from the trade of values that they are engaging in. From this point, it could be observed that hedge fund provides investors with a proper system that could allow them to earn as much as they expect given that they have good hedge fund managers who would be able to utilize numerous strategies that are effective enough to double the monetary value of what has been invested in the first place.

Fund of Funds

Understanding fund of funds

A fund of funds is an investment fund made up of a select group of mutual funds or hedge funds, and is usually used by investors with smaller assets than would be needed to invest directly into a hedge fund. There are many risks, advantage, and disadvantages associated with this form of investing. Fund of Funds is often defined as a form of mutual fund that is able to invest further and earn more from other mutual funds. Therefore, to be able to understand what fund of funds stands for fully and that of its nature it is first important to note what a mutual fund is. A mutual fund is noted to be a collective institution that handles the management of the monetary investment of several individual investors. Basically, the institutions handling such responsibilities are taking the role of manipulating how the monetary assets of investors would grow as expected while still getting something for themselves in form of fees. Mutual fund institutions often provide the investors a chance to expand the power of their investments through investing in several market securities and then distributing whatever is earned by each investor based on a pro rata measurement.

In a way, hedge fund investment is one particular type of a mutual fund while the funds of fund investment vehicle is another. Funds of fund operate along the process of diversifying the sources of income that one particular investment could incur. To do so, the fund of funds system embraces the process of holding shares in different mutual funds. This allows the investment to earn more within a shorter span of time thus doubling the capacity of the economic value of the investment to earn profit from the market. Usually, the shares that a fund of funds hold are related to open-end funds only. This way, fund of funds could be categorized to be fettered or unfettered; fettered being that the investments have holdings within the same investment company and unfettered being that the investments are allowed to incur some holdings on external investment organizations.

How Funds of Funds Work

Fund of funds investment policies are often offered at lower capital costs, making it easier for individuals to divide whatever money or asset they are willing to risk in the market. Fund-of-funds pool investor money and invest it in hedge funds. Investors in funds-of-funds pay fees charged by the fund-of-funds, typically 1.5% and 10% in management and incentive fees, and the fees charged by the underlying hedge funds, usually 1.5% -2% and20%. It would make sense for an endowment manager or chief investment officer assessing the use of a fund-of-funds to look at the “double” fee structure as a costly alternative to direct hedge fund investment. Founded upon the concept of the Modern Portfolio Theory[1], the establishment of diversification of earning procedures and possibilities has been realized to be the primary advantage of fund of funds system of investment. It basically maximizes the portfolio returns while strongly minimizes the risk that the investors could incur from the agreement.

What fund of funds offer

The million-dollar buy-ins and volatile risk structure of hedge funds made hedge funds an exclusive investment vehicles only for the rich and powerful, but now fund of funds give lower income investors a gateway into hedge fund investing. Some advantages of funds of funds offer that Hedge funds do not deal with asset class. Hedge funds essentially make up their own asset class, which can be very vague. There are a pool of seedy of hedge fund managers flooding the market making it almost impossible to identify the credible ones. To put forth all of the effort necessary to decipher the complex world of hedge funds, and the pool of hedge fund managers, is no easy task for a new investor. A fund of fund serves as an investor’s safeguard against mistakes in this aspect. “Ang and others further note that, the promoters of funds-of-funds offer an number of arguments in their favor. First, they allow investors to obtain exposure to hedge funds that are otherwise closed to new investments. Second, funds-of-funds generally have much lower required investment minimums than those required by hedge funds and they provide investors access to a diversified portfolio of managers (Ang, Rhodes-Kropf & Zhao, 2008).” The authors identify this as an aspect of fund investing that only an investor with large amounts of capital could replicate.

They further note that funds of funds perform professional due diligence, oversight, and manager selection of the hedge funds in its portfolio, so the investor doesn’t have to waste the time (Ang Rhodes-Kropf & Zhao, 2008). Funds of funds in many ways are an introduction to individual fund investing without all of the risk and responsibility. Funds of funds have an advanced in-depth due-diligence process that involves background checks of hedge fund managers. In addition to searching for a disciplinary history within the securities industry, this work can include researching the backgrounds of associates, verifying the credentials and checking the references provided by a hedge fund manager who wishes to be chosen for the fund of funds.

The allocated amount for hedge funds and high minimum investment levels prevent diversification. Funds of funds provide investors who have limited capital instant diversification through access to a number of fund returns with single investment. The fund selection process can provide lower volatility returns by spreading assets over a wider spectrum of strategies. Where hedge funds assume the risk of selecting one individual manager, funds of funds provide a portfolio of managers with a single investment. Aside from the lower-risk-higher-return policy of its procedural application, fund of funds investment scheme provides the investors a chance to see how much their investment grows on a regular basis. Also, they are given the capacity to withdraw the amount they have earned whenever they feel that they have earned enough from the industry. Fund managers however may specifically convince them to retain their investment within a specific span of time for the sake of gaining the best benefits possible as the performance of their assets reflect during past quarter transactions.

The fee structure of fund of funds

As Brown, Stephen, and Liang note, “Both FOFs and hedge funds typically charge an incentive fee expressed as a percentage of fund returns over a specified benchmark (Brown, Stephen, & Liang, 2004).” Fees are the price of admission when it comes to investment vehicles of these types. There is no set fee schedule and investors are well aware they will eventually have to pay them, but the question arises, how much of a factor do they really play in valued returns?

In most cases, hedge funds charge asset-based fixed fees that range between 1-2%, but these fees can range between 3% and 4% annually. Performance fees can also come into play and they can run between 10-40% of the capital gains. Performance fees are usually structured to have a “high watermark;” this means the manager cannot retrieve them until the fund recovers any previous losses. As noted by Brown and authors, “There is no uniformity in fee schedules across funds. A wide variety of benchmarks and High watermark provisions are commonly in use, and in some cases, incentive fees are in fact a nonlinear function of return. In a small minority of cases these fees are dependent on the size of the investment with a discount offered for large fund holders (Brown, Stephen, & Liang, 2004).” Before assessing how fees are distributed to primary actors within a fund of funds, it is first important to consider who the actors are and what roles they play in the process. This can be understood in more detail by looking at the diagram shown below:

As seen in this diagram, the primary fee structure starts with the manager. The manager serves as the primary bridge between the investors and the securities market through establishing a structured course of diversified investment intensifies their required fees from their clients.

(Lintner, 1999)

This means that at some point clients or investors have no choice but to pay the fees that the managers require from them.

The performance of managers in assuring investment returns basically creates a conditional process by which the investors are able to realize the compensation for whatever fee they are providing their managers. In regards to Management fees and incentive fees respectively, Ang notes, “The median management fee for both hedge funds and funds-of-funds is 1.5%. Funds-of-funds have median incentive fees half the size of the median incentive fees for hedge funds, at 10% and 20% for funds-of funds and hedge funds, respectively. Approximately half (56%) of funds-of-funds have high watermarks, whereas the proportion of hedge funds having high watermarks is 65% (Ang Rhodes-Kropf, & Zhao 2008).” Based on fund type, these discrepancies in fee structure result in average returns and alphas for funds of funds that are lower than those of hedge funds. The authors specifically note that, “the median monthly excess return for funds-of-funds is 0.35% per month, which is lower than 0.46% per month for hedge funds (Ang Rhodes-Kropf, & Zhao 2008). The monthly return rates show that the average fund of fund underperforms the simplest hedge fund benchmark. The authors point out that anyone assessing these numbers would come to the conclusion that funds of funds don’t add value relative to hedge funds. They then do an in-depth analysis of comparing funds of funds to hedge fund to disprove this theory and reveal what should be the true fund of fund benchmark. There position on this topic explained in more detail below in section 4.

Funds of Funds vs Hedge Funds

Ang and authors note that comparing average risk-adjusted returns across two asset classes is only valid when both asset classes can be directly compared (2008). It is their view that funds of funds and hedge funds are not directly comparable for the following reasons:

- “First, the best hedge funds are closed (presumably filled with the capital of smart investors who recognized the superiority of these hedge funds at an early stage).”

- “Second, even if a wealthy investor meets the high minimum requirements for investing in hedge funds, there is no guarantee that a successful hedge fund will take that investor as a client.”

- “Third, and most importantly, unlike listed stocks that must provide timely disclosure notices and accounting reports, hedge funds are often secretive with little or no obvious market presence.”

(Ang,Rhodes-Kropf, & Zhao, 2008)

The authors take the position that it would be more realistic to assume that fund of fund managers and individual investors have disproportionate skill-sets and access to information when it comes to making these types of investments. They basically believe that the human element that does not show up in the numbers plays a significant role in choosing either hedge funds, or funds of funds as a viable investment. In regards to the lone individual investor trying to choose between these two fund models, the authors note that if one considers realistically how an individual investor would approach comparing funds of funds to hedge funds, they would realize that, “This investor is not comparing a fund-of-funds to the set of hedge funds in a published database. Rather, she is comparing the fund-of-funds to the set of hedge funds that she can locate, evaluate and invest in by herself – without using a fund-of-funds.” They say this because data on hedge funds is very difficult to retrieve, so the skill and expertise of the particular investor must be factored into the equation. Depending on the type of investor, Funds of funds is a more viable option for investing, the authors further enforce this when they say, “We estimate the implied benchmark distribution for funds-of-funds for different types of investors. We find that it is not hard to justify the use of a fund-of-funds and the conditions under which investors choose a fund-of-funds over hedge funds are economically reasonable and plausible. This is particularly true for smaller and more risk-averse investors (Ang, Rhodes-Kropf & Zhao, 2008).” This is significant, because they are not arguing that funds of funds are comparable or equal, they are saying that it’s reasonable to view funds of funds as a better option. This is because the probability an individual investor with limited skill will select a successful hedge fund, much less one that they can skillfully monitor, is very unlikely.

The authors take this concept even further responding to a common assertion that if data shows hedge funds perform better on average than funds of funds than it would be expected an investor could pick a hedge fund at random and that fund would outperform the average fund of fund. In response to this the authors note that,

This is not true because the data are furnished by hedge funds and funds-of-funds which themselves are the result of an equilibrium where investors with different skills sort themselves into direct investors in hedge funds and indirect investors through funds-of-funds. The return differences from these hedge funds and funds-of funds that have received capital from these two types of investors do not directly answer the question of whether funds-of-funds add value relative to hedge funds.

(Ang, Rhodes-Kropf & Zhao, 2008)

Here the authors prove that average returns have no bearing on whether or not funds of funds add value. This is all assumes that a particular investor is even able to invest in a particular hedge fund of their choosing, as the authors had previously pointed out that the best funds are quickly filled by skilled and informed investors. In addition, hedge fund managers are highly selective of who they allow to invest. The fact that hedge fund databases only contain returns of hedge funds that have been funded directly by skilled investors (Ang, Rhodes-Kropf & Zhao 2008), the authors propose this creates an upward funding bias in favor of hedge funds. This bias leads to revealing the true benchmark based on which funds of funds returns should be compared to hedge fund returns. Data available for study to evaluate funds of funds performance compares funds of funds only to hedge funds that are funded by skilled investors. As the authors note this data is, “too good relative to the true universe of hedge funds. We never observe the bad hedge funds that would have received funding if funds-of-funds did not exist (Ang, Rhodes-Kropf & Zhao, 2008).” The true hedge fund distribution, one that accounts for this bias, is the actually benchmark for funds of funds; and it is found in empirical data (see part 2) that when funds of funds are compared to hedge funds based on this criteria, funds of funds turn out to be a safer more profitable investment over time deserving of their fees of fees.

Part 2

Measuring the Benchmark of Fund-of-Funds

Background

Incorporated in this section are charts, graphs, and tables of empirical data that will further enforce the theory that funds of funds are deserving of their fees of fees when their value of return is assessed relative to a true benchmark. As it was previously pointed out, when funding bias is removed from the equation, funds of funds and hedge funds are compared on a more equal playing field. As Ang puts it, when the fund bias is removed, “…investors have higher hurdle rates before preferring to use direct hedge fund investments or investors need to believe in fewer basis points of underperformance relative to a typical TASS hedge fund before they prefer a fund-of-funds (Ang, Rhodes-Kropf & Zhao, 2008).” Here it’s clearly stated that when true benchmarks are assessed, that hedge funds don’t need to underperform as significantly for funds of funds to be the preferred investment. This is not to confuse the statement with meaning that funds of funds on average outperform hedge funds, because they don’t annually. However, it does imply funds of funds true returns are close enough to hedge fund true returns for the significantly higher level of stability they provide to be taken into account.

Understanding Value Returns

Do funds of funds add value? The answer is yes, and the following will demonstrate how. Value returns are defined as the primary profit that an investment earns within a specific dedicated schedule that has been agreed upon. Usually, the investor and the institution where he invests his money create an agreement regarding this matter. It could be that the offer of the institution is based on a quarterly earning scheme or even on annual determination of profit. The way funds of funds returns are valued relative to those of hedge funds is most commonly based on the returns reported in public databases. Andrew Ang , and supporting authors argue this is not an accurate method. Ang notes,”…funds-of-funds should not be evaluated relative to hedge fund returns in publicly reported databases. Instead, the correct fund-of-funds benchmark is the set of direct hedge fund investments an investor could achieve on her own without recourse to funds-of-funds (Ang, Rhodes-Kropf & Zhao, 2008)” Many returns hedge funds report are the results of investing funds provided to them by funds of funds. Funds of funds, which are also influenced by the performance of these hedge funds, good or bad, are then measured on a scale relative to these returns. It is understandable why Ang would view this as a conflict of interests as a “bias truncated upward in favor of hedge fund returns (2008).” No matter what the choice is, fund of fund or head fund, these reports are what give investors a supposed distinctive line of expectation.

Empirical Data Section 1:

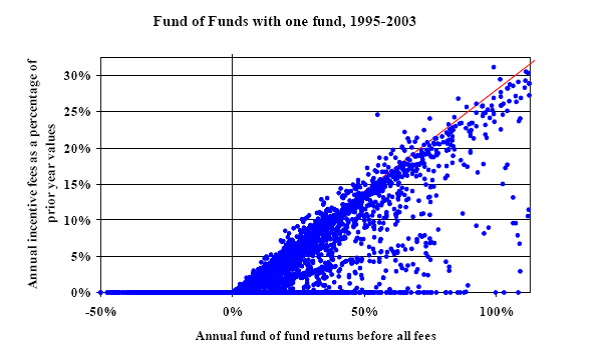

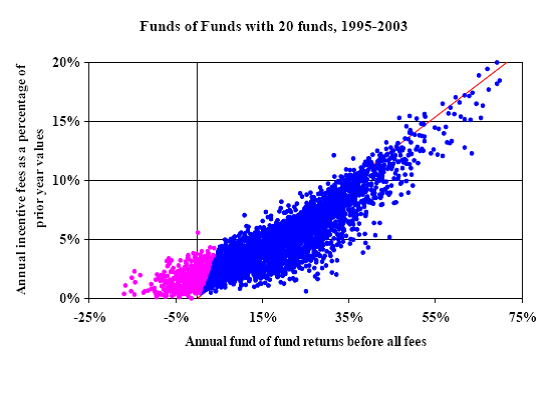

Funds of funds Number of funds as they relate to Valued Returns: The graphs show how funds of perform based on the number of funds in which they are invested, and how it actually effects the incentive fees applied.

(Brown, Stephen, & Liang, 2004)

The above chart demonstrates that while funds of funds incentive fees increase over time, it’s in response to returns. It also demonstrates that funds of funds are valued investments in the long run ultimately out earning the fees they incur. Finally it shows how funds of funds perform when only invested in a single fund.

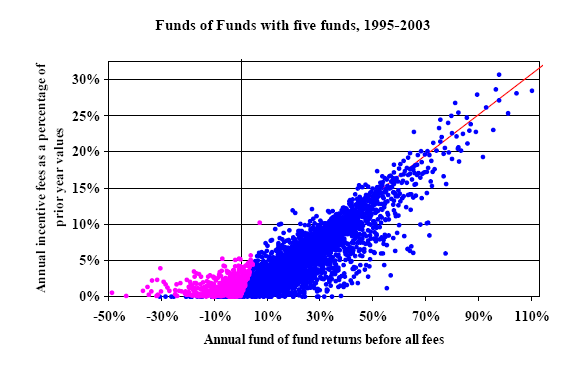

(Brown, Stephen, & Liang, 2004)

Here it’s clear that it’s more beneficial to both funds of funds managers as well as investors for fund of fund firms to have more than one fund on their portfolio. The result is higher returns and there is a clear outperformance of fees. The value return is one where the incentive fees stay the same as they would with a single fund on the portfolio, but there is a higher principle return.

(Brown, Stephen, & Liang, 2004)

The above chart demonstrates that there is a plateau in the annum earnings when a fund of fund becomes too diversified. Even if the fund performs exceptionally well, at this level there are bound to be some levels of averaging down across the board, due to mediocre to low performing investments. Incentive fees and fund returns in the chart are lower due to this leveling out. At this level of investing, there are so many variables that can affect performance, but also the more the returns level out and retrace backwards, the lower the volatility and risk and the more solid the fund becomes as a long term investment.

Empirical Data Section 2:

Funds of funds Volatility as it Relates to Valued Returns: The empirical data below displays how funds of funds perform to earn valued returns in comparison to other benchmarks, such as hedge funds, U.S. bonds U.S. equities and foreign equities.

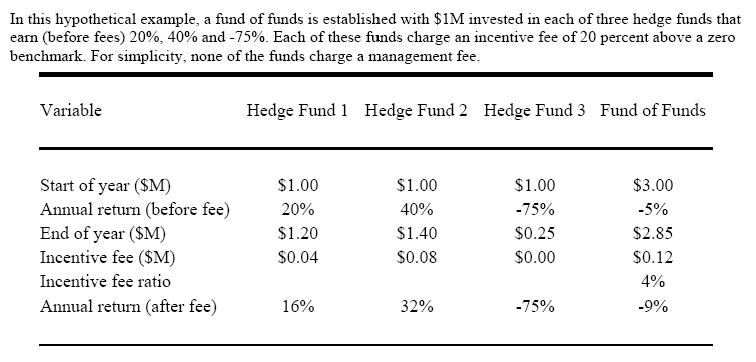

(Brown, Stephen, & Liang, 2004)

In the table above a fund of fund is both compared to three hedge funds within its portfolio as well as compared to their individual performance. In addition to this table being a perfect example of fund of fund performance, it is also reinforces Ang, Rhodes-Kropf and Zhao’s position that a true funds of funds benchmark is based only on average hedge fund returns of those firms that have received absolutely no funding from funds of funds (median returns of both the reporting firms and non-reporting) (Ang, Rhodes-Kropf, & Zhao, 2008).

The table above is a perfect example of how funds of funds hedge against risk better than hedge funds, but it also shows how by taking less risk, funds of funds reap lesser rewards. Notice how investing entirely in hedge fund 3 would have resulted in a 75% annual loss, but the diversification offered by the fund of funds investment model resulted in a balanced out return and averaged out the annual loss to 9%. It can be argued that if all of the hedge funds could have declined and a major loss would have still been incurred, but that is less likely than the possibility of taking on a great loss with one particular hedge fund. Once an investment has bottomed out, it is completely gone, but if a portfolio is diversified, then there are always alternative investments on-hand to keep those that decline during certain spans afloat.

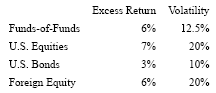

NBER recognizes the value of return as what’s left to the investor after the deduction of all the fees involved in the process of completing the transactions of investment (Ang, Rhodes-Kropf & Zhao, 2008). How much volatility a funds of funds exposes an investment to verses that of a hedge fund could substantially affect the value of return. . Investing directly into an individual hedge fund has become synonymous with taking on massive risk in the pursuit of ample returns, likewise investing in U.S. Bonds is recognized as a safe way to minimize volatility and make a consistent modest return on investment. According to research done by Yale Endowment, cited by Ang, Rhodes-Kopf and Zhao, funds of funds could be the perfect middle point between these two types of investments, providing the perfect balance between volatility and stability, investment and return. The empirical evidence below demonstrates this in further detail:

Yale Endowment: Excess Returns & Volatility Rate:

(Ang, Rhodes-Kropf & Zhao, 2008)

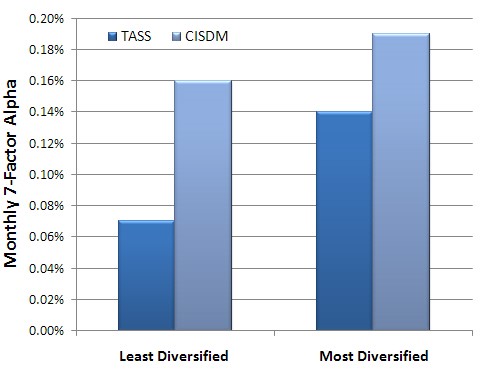

Here it is made very clear that the stability funds of funds provide is comparable to that of U.S. Bonds. Likewise, U.S. equities and foreign equities which are heavily invested in by hedge funds show a volatility of 20%, 7.5% more than funds of funds. This suggests that funds of funds are significantly more stable and less risky than hedge funds. In fact, there are more current studies that suggest the funds of funds investment model allows for levels of diversification unattainable by hedge funds that could lead to high alphas. Alphas is a measurement of performance that adjust based on risk. It takes the volatility price risk and compares its risk adjusted performance to the benchmark. The excess return above the benchmark is the alpha. The chart below, from a 2011 report on “Diversification Strategies and the Performance of Funds of Hedge Funds” done by Albany University, shows that when funds of funds diversify across hedge fund strategies and managers they produce higher alphas.

(Dai & Shawky, 2012)

Here we see the more diversified a fund of fund is the higher alphas its projected to produce. Basically, the probability that a fund of fund will exceed its benchmark is increased the more it diversifies across both hedge fund strategies and managers. This is an additional benefit to investing in funds of funds verses hedge funds.

Hedge Funds vs Funds of Funds

Characterizing the Benchmark Fund of Funds Hurdle Rate

(Brown, Stephen, & Liang, 2004)

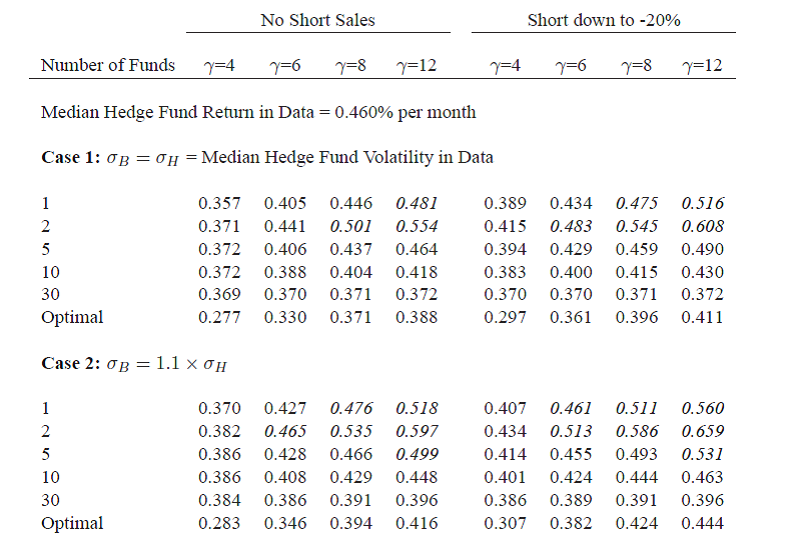

In relation to the table presented above, it should be recognized that the NBER study, by Ang(2008) and his colleagues, found that the investment on fund of funds did increase the diversification characteristic of the invested capital. Nevertheless, the returns which are considered to be at 0.460% per month were noted to have the capacity to be lowered down in relation to the subtraction of the different fees that the investor had to pay their fund manager. With the market’s volatility, such loss on fees could be further redeemed through making sure that the diversified securities shall perform at their best during the time when the investment is invested under their policies. Case 1 in this chart represents a scenario where the median cross section standard deviation is equal to the median cross section standard deviation of hedge funds, based on four benchmark assets set for funds of funds (U.S. equities, U.S. bonds, foreign equity, and foreign bonds), the authors found that when the median cross sections standard deviation was similar between funds of funds and hedge fund returns that investors were indiscriminate about which fund invest their assets. In Case 2 the median for funds of funds is higher than that of the hedge funds, and the authors found in this case investors preferred funds of funds regardless of knowing they could get higher returns on their own with hedge funds. The authors go on to reveal the deciding factor that certifies beyond a doubt funds of funds deserve their fees of fees and are a more viable investment than investing in individual hedge funds. They argue this distinguishing element can be found in the hurdle rate.

Hurdle Rate: The Deciding Factor

The hurdle rate, in this case, refers to the minimum rate of return on an investment required by the funds manger, specifically the rate of return the fund manager must beat before collecting incentive fees. Ang, notes that

y= 6 investor who cannot short and is considering a single hedge fund versus a fund-of-funds has a hurdle rate of 0.332% per month… versus 0.405% per month using historical inputs for means and variances. This is a difference of just 0.073% per month and well below 1% per annum. With an average hurdle rate of approximately 0.3% per month a typical investor only needs to think that she would do approximately12x(0.46–0.3) = 2% per annum worse than the reported median hedge fund return in TASS before preferring a fund-of-funds.

(Ang, Rhodes-Kropf, & Zhao, 2008)

Here it’s made clear that a, more than likely to occur, 2% drop in the average hedge fund annum return makes the funds of funds a better investment, due to its guaranteed potential for growth over the long-term and the hedge funds structure’s expectation for dips and volatility. The hurdle rates are the deciding factors because they reveal this core difference between the two investment models. The author concludes all of this in laymen’s terms means the notion that funds of funds are likely to add value is extremely likely and probable (Ang, Rhodes-Kropf, & Zhao, 2008). Most importantly, it confirms that funds of funds are actually a more solid investment option than hedge funds over time, because they are more likely to survive severe downtrends in the market.

Funding Bias

Funding bias often refers to the tendency of scientific studies shape research outcomes in favor of their sponsors. In the case of investing there are two core issues that need to be addressed, reporting bias and funding bias. Reporting bias is actually a non-issue but adds credibility to funding bias as a fiduciary concern. Reporting bias deals with successful and unsuccessful hedge funds alike. The authors note that,

The hedge fund databases tend to contain returns only of hedge funds that are funded directly by skilled individuals and funded indirectly through unskilled investors using expert funds-of-funds. The data truncate the returns of most of the worst hedge funds that would have received funding from unskilled investors if they could not use funds-of-funds. Consequently, the observable set of hedge funds is biased upwards compared to the true set of hedge funds that would be available only to unsophisticated individuals.

(Ang, Rhodes-Kropf, & Zhao, 2008)

In reality as the authors go on to note, the successful hedge funds that do not report to hedge fund databases create an observed hedge fund return report that trends downward. This is seen as a downward bias because it’s influenced misinformation. Likewise, those unsuccessful hedge funds that don’t report are also influence the average. This makes the overall hedge fund return report trend towards the middle with what the authors call a bias towards mediocrity. The difference in reporting is that there is really no way to suggest that funds of funds influence hedge funds that report returns or don’t report. The relationship between funds of funds and hedge funds comes into play with the concept of funding bias. Funding bias involves hedge funds that have received funding and reported it verses those that have not reported it to a database. The reason this is important, as has been previously show, is it effects the validity of benchmarks.

Conclusion

In sum, funds of funds deserve their fees of fees. This assertion is based on the fact that when comparing fund of fund returns to hedge fund returns based on their true benchmark, the performance results are narrowed and nearly uniform between the two. While hedge funds on average still seem to outperform funds of funds, the difference is minimal when certain elements are also accounted for in the equation. One of these elements is the human element, specifically factoring in the skills and resources of individual investors looking to invest in hedge funds compared to those of fund of fund managers. Another element involves funding bias and how it influences the real benchmark and hurdle rates dictating how fund performance is measured. While the top performing hedge funds may far outperform the top fund of fund firms, those select hedge fund are only accessible to an even more select group of investors. They also require a higher minimum investment. For investor with limited startup capital to access those particular hedge funds, their only real avenue is to invest in a funds of funds investment vehicle. While hedge funds may outperform funds of funds based on publicly reported databases, these returns are based on a benchmark that does not account for funding invested directly into hedge funds from funds of funds. The true benchmark is the set of returns a hedge fund can earn without the support of funds of funds. When this discrepancy is accounted for, it becomes clear that funds of funds are a comparable alternative to hedge funds.

References

Anson, Mark J.P. (2006). The Handbook of Alternative Assets. John Wiley & Sons. p. 36.

Ang, Andrew; Rhodes-Kopf, Matthew and Zhao, Rui. (2008). Do Fund of Funds deserve their Fees of fees? NBER Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge: Massachusetts.

Brown, Stephen and Liang, Bing. (2004). Fees on Fees of Funds of Funds. Yale ICF Working Paper: YALE International Center for Finance. Amherst: Massachusetts.

Blazenko, George W. (2009).”Corporate Leverage and the Distribution of Equity Returns,” Journal of Business & Accounting, p. 1097-1120.

Dai, Na and Shawky, Hany A. (2012) “Diversification Strategies and the Performance of Funds of Hedge Funds” Albany University

Ineichen, Alexander. The Alpha in Fund of Hedge Funds: Do fund of Hedge Funds Managers add Value? http://www.eurekahedge.us/news/attachments/fof_alpha.pdf. (Retrieved on June 19, 2012).

Fama, Eugene F.; Merton H. Miller (June 1999). The Theory of Finance. Holt Rinehart & Winston.

Lintner, John (1999). “The Valuation of Risk Assets and the Selection of Risky Investments in Stock Portfolios and Capital Budgets“. The Review of Economics and Statistics (The MIT Press) 47 (1): 13–39.

Samuelson, Paul, “General Proof that Diversification Pays,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 2, March 1967, 1-13.

Samuelson, Paul. (2001). “Risk and uncertainty: A fallacy of large numbers,” Scientia 98. 108-113.

Sharpe, William F. (1999). “Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk“. Journal of Finance 19 (3): 425–442.

Ross, Stephen, “Adding risks: Samuelson’s fallacy of large numbers revisited,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 34, September 1999, 323-339.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee