Art Project: Picasso, Essay Example

Introduction

It is doubtful that any artist imprinted their persona on modern history to the extent that Pablo Picasso has. The Spanish-born artist, emerging as a major figure in the early 20th century, increasingly became an icon in his own right. His work, initially dismissed by many critics and far from embraced by the public, has always generated controversy. While destined to hang in the world’s greatest museums, Picasso’s paintings somehow still maintain an aspect of rebellion, and still draw forth criticism and interpretation of a heated kind. Picasso is rarely admired; instead, he is liked or disliked. Then, schools of thought strongly feel that much of what Picasso has been given credit for, in terms of artistic innovation and introductions of new styles, were in fact the achievements of others from whom Picasso liberally “borrowed.” Not only have individual artists like Matisse and Degas been implicated as having been the true sources of the innovations, this same belief holds that a great deal of Picasso’s primitive work was simply taken directly from studies of African art, largely unknown to the public at the time. To such minds, the greatness of Picasso lies chiefly in his talent for seizing upon the greatness of others.

At the same time, it is unlikely that any artist could have risen to Picasso’s stature simply by employing the techniques of other artists. In fact, Picasso never concealed that certain works presented him with subjects and inspirations, and in that sense it is true that he copied the greats of his time. More exactly, his artistic sensibility held that copying art was superior to being inspired by it, because in the copying the true artist will emerge to alter the original (Bently, Davis, & Ginsburg 329). As with so many other elements of his life and career, Picasso is here redefining what the artist means to the world, and where the true responsibilities of him lie. It was a career spanning the better part of a century and, for better or worse, one that forever established him as a titan in the field of modern art. There were periods of specific styles, explorations of sexuality, and thinly disguised political statements, but all of it is marked by a brand completely belonging to the artist. Criticisms notwithstanding, the body of work by Pablo Picasso exemplifies a triumph of an artist finding his way through channels of change and effort, and creating an artistic presence irrefutably all his own.

Background

The general circumstances and facts of Picasso’s life, and certainly his youth, obviously play an important role in the artist he was to become. At the same time, given the inherently mysterious processes by which art is created, it is unwise to look too deeply into such realities, for all reality is transfigured by an artist. It is natural, for example, to speculate that Picasso’s Spanish background and upbringing contributed to his sensuality, as well as to the defiant machismo his own personality manifested to the public. He was a grandiose character always, larger than life, and it is easy to ascribe this to the influences of a European culture. Nonetheless, Picasso was very much his own creation, so only a minimal examination of his life may be helpful.

Born in 1881, Picasso spent the first ten years of his life in Malaga, a Spanish town on the Andalusian coast. The family was far from wealthy, and a job teaching drawing secured by the father brought the family to La Corona in 1891. What is interesting here is that the boy was exposed to two completely different environments; Malaga was dreamy and soft, and inclined to the arts and casual living, while la Corona was far more provincial (Charles 10). Equally important is that Jose Ruiz, the boy’s father, taught the young Picasso the rudiments of drawing at a very young age. La Corona also had a School of Fine Arts and, owing to the father’s influence, Picasso took classes early. Moreover, it was noted that the boy never stopped drawing or sketching, even while home, and Ruiz encouraged the work. By 1895, the family had moved to the larger city of Barcelona, and the barely adolescent Picasso enrolled in the prestigious School of Fine Arts, La Lonja. It seems that, even then, conflict was emerging within the young artist. He wanted to placate his father and train in the traditional manner to become an artist, but he found the classes dulling and uninspired. Jose Ruiz responded by renting a studio for his son when the boy turned fourteen, and Picasso always cherished this time as one of extraordinary self-discovery (Charles 12). It is not difficult to imagine why. A spirited, passionate boy just in the midst of adolescence, free to explore his life and his art in a great metropolis, enjoys a rare opportunity, and Picasso made the most of it. Attractive to women even then, he devoted as much intensity to romantic affairs as he did to his early canvases.

Before he turned eighteen, Picasso was openly defying the strictures of academic instruction in art. Moreover, a period of eight months spent at the country home of a friend, located in Horta de Ebro and serving as a place to convalesce after a serious illness, changed the artist forever. He claimed that this brief time in the free, open country taught him everything he would ever know about painting (Charles 14). In the years following, he traveled on his own, studying in Madrid, and then settling in Paris. The boy was now a young man in his twenties, in the world capital of art. The rest, if a cliché may be excused, is history, as Picasso fell into the circle of immensely talented artists and writers who would give Paris that status. He would also, as the following will illustrate, become known for radical shifts in style, marking entire periods of artistic transformation. Many of these would become forever associated with his name, the contributions of other artists notwithstanding.

The Art

Perhaps more so than with any other legendary artist, the trajectory of Picasso’s work reveals the artist more clearly than can any biographical information, for his development as a man is captured in each phase of his work. In 1895, for example, at the age of fourteen, Picasso executed his Portrait of the Artist’s Mother.

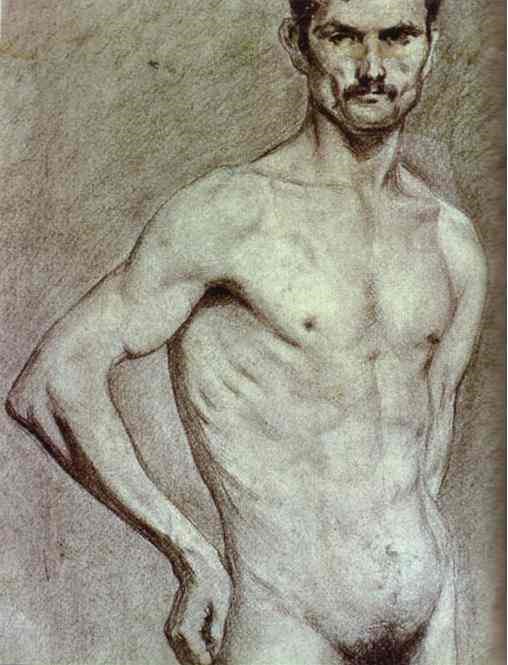

What is notable in this early work is Picasso’s adherence to classic form. It is as sedate and traditionally executed a work as may be found in his entire canon, and it is probable that Picasso’s intent was to adapt classic technique to idolize his mother’s image. That a young artist should wish to do so is not exceptional, but it is unlikely that many adolescent artists could have so effectively employed light and shading as Picasso does here. He had studied Rembrandt, Vermeer, and the other Dutch masters, and their skill with light is not lost on him. This is most effective in the halo effect surrounding the mother’s head. Equally of interest is that the portrait does not change the woman’s contours, or present her as more “glamorized”; her hair is somewhat disarranged, as her double chin is accentuated by the posture. The boy is both capturing the reality of the woman and rendering a loving, admiring tribute. In this same period, the boy seems to exult in his training, as in the 1897 sketch of the Matador Luis Miguel Dominguin.

In this pencil drawing, two aspects become apparent. The first is that study of the human anatomy as pioneered in art by Michelangelo and Da Vinci was taken seriously by Picasso. The musculature mirrors real life, from the shadows of the ribs to the sinews of the forearms. The other element lies in Picasso’s treatment of Dominguin’s face. It must be remembered that this was done when Picasso was sixteen, and the quiet ferocity of the matador’s face is an extraordinary achievement. It is real in a way few mature artists could render, in that it is subtly dramatic and completely lifelike. These dual abilities, in fact, mark virtually all of Picasso’s earliest work. The viewer can see where styles are being taken from the greats, almost as though a lesson in how to learn from the masters is being prepared. At the same time, there is also the sense of an independent presence guiding the brush.

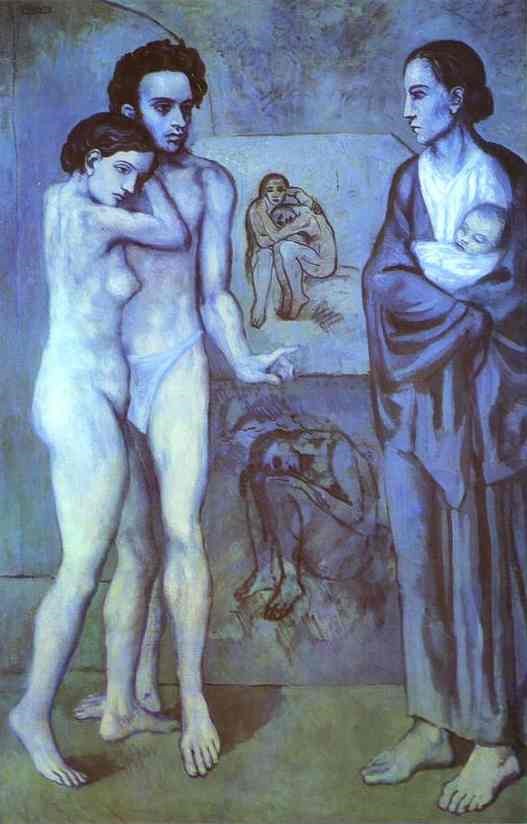

Early in the 20th century, the young Picasso increasingly opted for monochromatic palettes of only blue. He was, as in other techniques, by no means the first artist to take this direction; Gauguin, Degas, and Cezanne had all explored the style, using blue to dominate their paintings and convey a kind of primal sadness (Hunter, Jacobus, & Wheeler 134). Picasso’s famous Blue period lasted only for several years, yet it is remarkable in ways that the monochromism of other artists is not. More exactly, Picasso is never content in this phase of his career to allow the dominant color to make his statement, and this is exemplified by 1903’s La Vie, seen above. More importantly, and as this painting vividly demonstrates, the young artist was beginning to forge a style unique to himself. That this highly stylized form derives from the approaches of a combination of other artists is irrelevant, for art typically fashions itself into an entity all its own through this very process. What matters here is that Picasso is creating keynotes which will be reflected in much of his most mature work, and perhaps the greatest of these is a deliberate tension created by ambiguity. On one level, the canvas relies on traditional symmetry, with the woman and infant on the right balancing the young couple to the left, and twin images of other life set between them. On another, multiple meanings may be taken from the presentation, for it has the effect of being an entire drama, or scene. The hand of the boy is pointing up, in a gesture of correction, even as the woman looks on implacably. Meanwhile, the young girl reposes completely on the boy, seemingly removed from whatever conflict is in play. Consequently, essences of defiance combine with a feeling of intense familiarity, and the impression is of a family drama unfolding. More to the point, the shades of blue employed then translate to, ironically, a less pronounced component; they act more as a lighting effect than a vital element of the picture, and merely establish mood. It may be argued, then, that a lesser artist, opting to indulge in a Blue Period, would rely more on the color to present his artistic vision. With Picasso, it is nothing more than an adjunct to the art itself.

Regarding Picasso’s Harlequin Period, directly following the Blue, the actual focus and intent of this time may best be examined through a painting with no actual harlequin within it: 1905’s Two Youths.

In this work, other facets of Picasso’s range are coming into prominence. First of all, in discarding the use of the somber blues, he is blatantly embracing light, and in a way reflective of texture and the entire context of the work. The painting is by no means joyous, but it is illuminated in a manner giving an impression of freedom. Then, there is here the beginning of another style Picasso would turn to in later years, that of the model existing as a model. In his earlier work, there are efforts to classically render the human subjects as “caught off guard”; here, the boys appear to be positioned to serve the artist. It is also noteworthy that there is no attempt, as there is not in La Vie, to capture anatomical correctness. Now, Picasso is moving toward the more important object of spirit, or true being, as he also takes the courageous avenue of attempting this through simplicity of line. The forms of the boys are as bare of embellishment as the vases behind them, or the block serving as a seat, yet they have distinct dimension. In a sense, this is Picasso exploring the most simple of techniques to arrive at artistic truth, before he abandons this last means afforded by realism and embraces the Cubist.

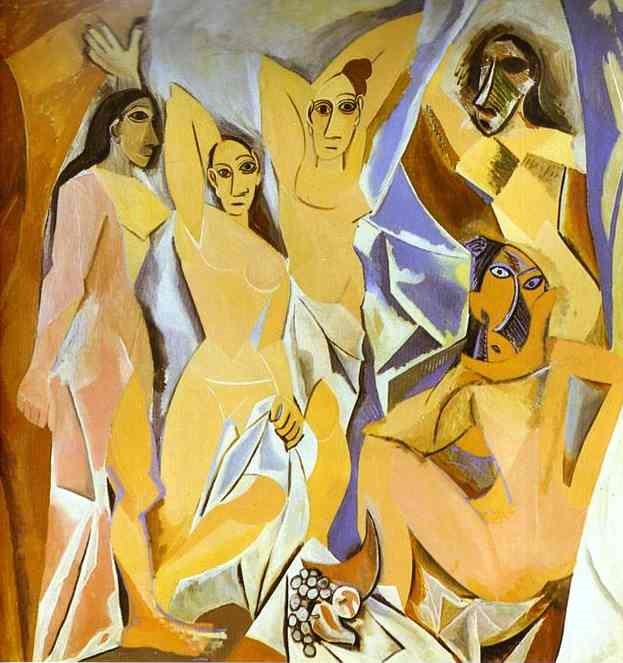

1907’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is certainly one of the most recognizable works of art known to man, and is typically used as the ultimate example of Cubism. Picasso most certainly did not invent Cubism, as the artists of his day, like Matisse, were already experimenting with the intensely sculptural, abstract style. It was, in fact, Matisse who pioneered the movement, strongly inspired by primitive art’s distortion of the human shape (Hunter, Jacobus, & Wheeler 71). This in no way diminishes Picasso’s achievement, however, for he translated the style in a way uniquely his, largely through incorporating a sense of animal power in the otherwise sterile imagery. This is a painting that warrants a great deal of study, simply because Cubism is, as with the blue of the Blue period, only another canvas upon which Picasso may exert his artistry. This artistry gave Cubism its integrity, in the minds of the art world: “It was Picasso whose volcanic genius undoubtedly transformed Cubism into the irresistible force it became for over half a century” (Hunter, Jacobus, & Wheeler 132). To properly appreciate what Picasso achieves here, it must be understood that Cubism existed largely to isolate traditional ideas regarding humanity from human form. More exactly, this was a school of art almost political in its ambitions, determined to analyze, rather than reproduce (Wallis 42). This, Picasso most certainly does, yet he does it with an emotive savagery absent in other Cubist works. He actually employs the dispassionate effect of distortion to amplify human essences, rather than objectify them, and his prostitutes of D’Avignon profoundly reveal this. Perhaps most striking is the female to the far right, for she is both Cubist abstraction and ferocious beast. In a powerful juxtaposition of style, the shaded diamond representing her breasts lies just below the snout of a tribal animal. Similarly, the reclining posture of the woman below her is belied by a mask indicating a ritual or divine presence. In this tableau – also blatantly using the figures as only models – multiple worlds of impression and feeling are conveyed simultaneously, for the Cubist element underscores the animal vitality of the women, and of the roles they play in life.

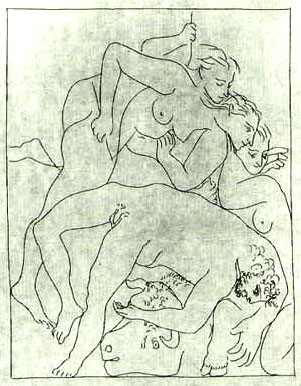

In no uncertain terms, Picasso was consistently drawn to sexual imagery. His many sketches of bulls reinforce their presence in a variety of his paintings, and it is widely felt that, for Picasso, the bull represented an alter ego of himself, and one relentlessly dominating and heterosexual (Berstock 168). However, as iconic as the sexual force of the male is for Picasso, there is also the aspect of the bull’s sacrificial meaning that the artist exploits, and this is important. More exactly, if Picasso was relentlessly sexual in much of his work, the sexuality is rarely overt, and is always subject to interpretation. That he identified himself with the hyper-masculinity of the bull is not disputed, but he also comprehends the inevitable weakness of such a presence. His bulls represent, but they rarely dominate or control his canvases, and some reveal surprisingly soft characteristics. In the 1930 etching, Eurydice Piquee par un Serpent, a great deal of Picasso’s ambiguous approach to sexuality may be seen.

This retelling of the Orpheus/Eurydice myth is astounding in a variety of ways, all of which relate to the others. On one level, the Maenads killing Orpheus are more “masculine” than the man, towering over him to exact vengeance and holding to one another in a sexually-charged manner. Then, there is the presence of the bull or Minotaur below Orpheus, transformed from a danger to an embraced ally. Tellingly, the genitals of Orpheus are uppermost and completely vulnerable; it is his eye that the poet seek to shield, indicating the greater importance of sight to the artist. Equally importantly, Orpheus appears to be surrendering to the female aggression, which has been viewed as an expression of Picasso’s own psycho sexual conflict (Berstock 170).

A forceful male, he nonetheless saw himself “victimized” by women, perhaps merely because of his need for them, and his Orpheus is capable of the escape he himself is not. Here, then, sexuality in Picasso is rampant, but meaning is varied. The same may be said of the more sexually overt La Reve of 1937.

This is a painting frequently cited as evidence of a misogynistic streak running through Picasso’s work. The feeling is certainly explicable; in this portrait of his dreaming mistress, her serene expression is partially composed of what is unmistakably an image of a penis in her head, and the hands over her own genitalia compound the effect. At the same time, however, the question arises: does the painting reduce the essence of the woman, or does it instead simply capture a moment of sexual reverie enjoyed by a woman? The latter interpretation, in fact, goes to empowering the female, rather than diminishing her, because the masculinity is contained within her. Moreover, there is a distinct gentleness about the painting that belies any aggressive, hostile masculine expression. If the work reveals genitalia, it also displays sexuality in a composed, tranquil, and even loving form.

Conclusion

Pablo Picasso, no matter the negative critical views of his work periodically emerging, enjoys the unique position of being perhaps the most universally celebrated modern artist. That his work was often derivative cannot be disputed. Trained classically, and then moving away from classic styles early in his long career, Picasso openly and enthusiastically seized upon techniques and styles already being explored by other artists, from the monochromatic Blue Period to his extensive work in Cubism. Art, however, is derivative by nature, as all artists forge individual identities from the work preceding and surrounding their own, and what ultimately matters is that the identity reveal a new presence. In the final analysis, the entire body of work by Pablo Picasso reflects a triumph of an artist making his way through channels of change and effort, and creating an artistic presence undeniably all his own.

Works Cited

Bently, Lionel, Davis, Jennifer, & Ginsburg, Jane C. Copyright and Piracy: An Interdisciplinary Critique. New york: Cambridge University Press, 2010. Print.

Bernstock, Judith E. Under the Spell of Orpheus: The Persistence of a Myth in Twentieth-Century Art. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1991. Print.

Charles, Victoria. Pablo Picasso. New York: Parkstone International, 2011. Print.

Hunter, Sam, Jacobus, John, & Wheeler, Daniel. Modern Art, Revised and Updated, 3rd Ed. New York: Prentice Hall, 2004. Print.

Wallis, Jeremy. Cubists. Chicago: Elsevier, 2003. Print.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee