Concentration: Information and Behavior, Essay Example

Compare and contrast two major theories or models of information seeking that have been used to explain behaviors of a user group (e.g., by age, gender, occupation) of interest to you. Provide examples of how the theories/models were used from the literature. Explain how you would use at least one of these theories/models in your own research.

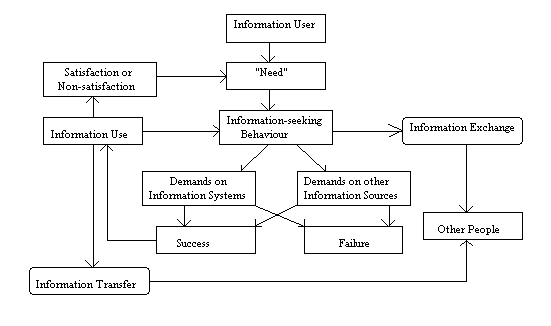

Information scientists have always been trying to put forward models for information seekin behavior of human. Every author has his own way and areas of interest in information research. These include Wilson (1981), Ellis (1993), Wilson (1999), Ingwersen (1996), Kuhlthau (1993) and Saracevic (1996).Some of these models have been tested to develop a ‘process’ of information seeking. Wilson (1981) has stated any form of analysis of the literature of information-seeking behavior must be based upon some general model of “information behaviour”. Wilson’s (1981) model appears below as it breaks down the function of “information need, information seeking, information exchange, and information use in a flow diagram that charted the behaviour of an individual faced with the need to find information” (Wilson, 1997, p.551). In 1981, Wilson put forward his first model of information seeking behavior. It focused more on the need for information rather than its use. His model also detailed the barriers to information searching behavior. The diagram below reveals the aspects of information seeking behavior which Ellis (1989) identified and Wilson adapted to incorporate into his model. as starting, chaining, browsing, differentiating, monitoring, extracting, verifying, and ending.

Fig.1. Wilson’s (1981) model of information behaviour

Wilson suggests that a general model such as the one above is helpful in regards to identifying gaps, voids, or areas in information behavior science research that might benefit from a more in depth assessment or innovative thinking. In regards to the barrier in the model and how it initiates as well as impedes information seeking behavior, Wilson argues that the above model reveals “the circumstances that gives rise to information seeking behaviour, the main elements of which are the situation within which a need for information arises (the PERSON performing a ROLE in an Environment), the barriers that may exist to either engaging in information-seeking behaviour or in completing a search for information successfully, and information-seeking behaviour itself”(Wilson, 1997, p.551). The model was amended in Wilson (1994) to show how Ellis’s (Ellis, 1989) work on information-seeking could be incorporated.

Wilson states that as an individual seeks information, he has to overcome the barriers of the process of seeking information. According to Wilson, “information need” is a vague and unknown to researchers. The need for information is not a need in itself, but is a means to satisfy other major goals. There are three basic reasons why an individual would seek information. They are physical needs (flood, clothing, shelter), psychological needs (emotions, enlightenment, domination) and Cognitive needs (learning a new skill, strategizing).

According to this model, each of the three basic reasons for information seeking are inter-dependent. For example, if a person needs physical shelter, he needs to learn how to build cognition. The environment and society dictate information seeking behavior. Although Wilson’s model explains the needs of information seeking of the individual and its barriers; it does not explain the way in which information is used. In later years (1997 and 1999) he has tried to expand upon the earlier research.

In contrast to the Wilson model; Ellis was interested in learning about how an individual retrieves the information. Ellis for empirical studies and put forward an eight point model in 1989. The features of this model are

- Starting – The first search to find information.

- Chaining- Following connections to identify new sources of information.

- Browsing- searching of primary and secondary sources of information.

- Differentiating – Distinguishing between information sources based on relevance.

- Monitoring- Awareness of new technologies

- Extracting – Locating the most relevant information

- Verifying- Validating accuracy of information.

- Ending – Using all the information to complete the activity.

Ellis mentions that these stages may not occur one after the other chronologically.

In 1997 based on Ellis list, Wilson mentioned that information need arises out of a situation (of the person’s environment, social roles and individual characteristics). That same context may pose barriers which must be overcome before he seeks information.

Both models are concerned with information behavior of an individual alone. They do not take into account collaborative information seeking behavior. In both models, the researchers focus only on information seeking activities alone, and not on the surrounding activities that may affect information behavior. The initial Wilson model was a broad model with a general scope. It was a culmination of several years of information research. The Ellis model was a popular model. It was also tested and studied with reference to a engineering company (Ellis & Haugan1997). Although, it is still general in nature, it can only be applied to scientists and information researchers. It is not appropriate for general public.

Wilson’s new model takes into account other fields that affect information behavior, such as, decision making, innovation, health and research. Wilson suggested that an individual’s motivation towards seeking information is driven by curiosity, risk factors, demography (age, sex), his/her role in society (student, manager, and relative), environmental factors and access to credible information. It is seen that there are other behaviors that affect information seeking behavior other than the 3 basic factors. Information behavior changes with an individual’s need to seek information and his/her exposure to available information. Information is evaluated based on its effect on need and the “feedback loop” in which one can reuse earlier received information to start a new query.

Information Need in Information Science

At the core of Wilson’s model breaking down information-seeking behavior is the concept of information need. Wilson argued in 1981, that information need is untraceable because it occurs only in the mind of the person in need. This means it’s not accessible to an observer. The experience of need can only be discovered by deduction from behaviour or through the reports of the person in need. This makes need subjective (Wilson, 1997, p.551). Bumkrant (1976) in his “Motivational model of information processing intensity, he refers to need “a cognitive representation of a future goal that is desired” (Bumkrant 1976, p.). Despite this perception the model of motive comes into play when attempting to assess the value of need and its impact on information behavior. Morgan King is credit for making this connection in Wilson’s work when Wilson states, “needs emerge from three kinds of motives: physiological motives (for example, hunger and thirst) unlearned motives (including curiosity and sensory stimulation), and social motives (the desire for affiliation, approval or status, or aggression), which accords in part with Wilson’s (Wilson, 1981) analysis of needs being cognitive, affective, or physiological” (Wilson, 1997, p.551). It is for this reason, that motive has a general use in information seeking studies. In fact, the concept of motive assumes that there must be an attendant motive actually to engage in seeking behavior in response to a given information need.

Furthermore on the theory of motive, Wilson (1997) state that, “within the general theory of motivation it is suggested that, when a motive is activated, a belief-value matrix within the individual is called on” (Wilson, 1997, p.551). The idea of motive is also a core aspect of Burnkrant’s (1976), gratification theory. Within the field of mass communications research, gratification theory assumes that an audience has complex needs which it seeks to gratify. McQuail (1972) argues that there are four main categories of gratification, that can be classified as affective needs:

- Diversion: escapism, emotional release

- Personal relationships: companionship, social utility

- Personal identity: comparison with life; reality exploration; value reinforcement

The above is a list of cognitive needs, for example, the need for one to find meaning within their environment, or the need to to satisfy or express curiosity. These type of cognitive needs can be drawn from information needs, and result in becoming motives for informational behavior.

Examples of these theories/models in literature

Since the emergence of internet, various web based portals have come up that cater to the information seeking behavior of an individual. In Rosenthal et.al (2010), the authors made use of the Wilson’s model to study information behavior in cloud computing. It takes into account human behaviors of trust, risks associated with information sharing. In Simon et.al (2009), the authors studied information sharing in the healthcare sector. Here the researchers studied patient – doctor or patient – healthcare provider relationship with emphasis on parameters like trust, privacy and legal implications of information behavior. In Lokman et.al (2003), the authors revisit Ellis’s study in the social study field and found that a fuller description of the information-seeking process of social scientists studying stateless nations should include four additional features besides those identified by Ellis. These new features are: accessing, networking, verifying, and information managing (Lokman and Tibbo 2003). This current research deals with a variety of backgrounds and experiences. It propose to use a combination of models based on literature. This study attempts to understand the importance of smart-phones in sharing and exchange of information. Smart-phones are considered to be the latest technology sensation. The standard mobile phone, personal computers and PDAs have been rendered useless by this new affordable, compact, and easy to use device. In every walk of life, the smart-phone has integrated itself. From the time we wake up, the morning exercise calculators, the to-do list for the day, recipes for meals and maps to navigate, are now at our fingertips.

Since the device we chose is so widespread, it will require studying of collaborative information behavior. As seen earlier, most models consider only the individual information seeker. However, we know from literature that collaborative behavior differs from that of a single individual. This is why the study propose the following broad aims based on the Wilson/Ellis model:

- How will an individual interact with digital information?

- Whether or not digital information access is dependent on demography?

- Will arenas to access new information be different for the general public as compared to researchers?

For this study, a longitudinal method combing a quantitative questionnaire and one on one qualitative (telephonic, electronic) interview will be used. The first phase of the study will involve looking at literature to learn about how individuals try to satisfy their information need. This part will take into account the different age groups and gender related differences.

The second part of the study collects evidence revealing how everyone approaches information in different ways. For example, do younger school children find it easier to source information from the net than older people?

The user population utilized in this experiment consists of :

- Temporary information seekers – People who look for “instant gratification”. Once their query is resolved, they would not look for more information.

- Avid information seekers – People who are constantly in the lookout for newer information. They look for information on diverse topics of interests.

- Browsers – Users that are still finding their way in the smart-phone environment.

- Cross- checkers – Users that test the validity of information.

Application of more than one model to this study will narrow its goals and make sure that the study contributes towards problem solving. The theoretical models will serve the following roles-

- Tools by which new research data can be analyzed for future use.

- Defining new research problems and proposing solutions to them.

- Finding facts among the accumulated information.

- Providing a frame of reference for researchers.

Communication Theories for the Internet Environment

Uses and gratifications theory, entails questioning what really motivates individuals to contribute to a “solution sharing network.” Lind (2009) argues that the uses–and–gratification in the theory can be used as a way to understand why people within a similar network use different forms of media to satisfy the same information needs. Lind (2009) presents this concept as a paradigm within media communication research, as it allows one the ability to determine motivation by studying the use of mass media. As authors note this can be done “to elaborate, motivations for use of mass media are determined by needs exhibited by people: cognitive, affective, personal integrative, tension release” (Cruz & Jamias, 2013, p23). Another example, of this can be seen with how people identify the television a s a form of entertainment but the internet is viewed as a method of information seeking (Straubhaar,et al., 2012). Use and Gratification theory can also be adapted to electronic communication to better understand how individuals satisfy their needs with electronic communication. Ruggiero (2000), emphasized computer–mediated communication and its interactive capacity noting that it creates a new set of needs, specifically, convenience, diversion, relationship development, and intellectual appeal. Stafford, et al. described in (2004) three key dimensions related to consumer use of the Internet, including process and content gratifications as previously found in studies of television, as well as an entirely new social gratification that is unique to Internet use. Ko, et al. (2005), after investigating a marketing Web site in 2005, discovered four dimensions of Internet usage and gratification, these beings entertainment information, convenience, and social–interaction motivations. The authors revealed that consumers with high information motivations are more likely to engage in human–message interaction blogs, mini-blogs, websites or forums. These users are also likely to interact using social media tools.

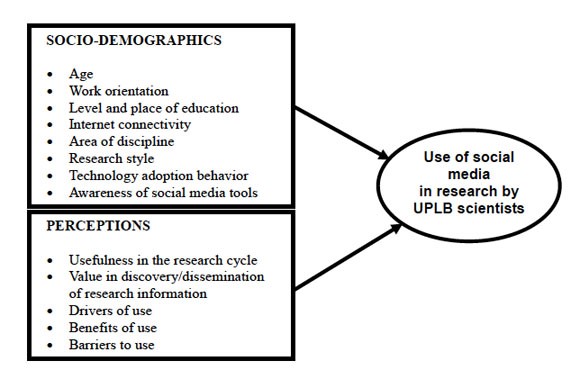

The U&G approach has been regarded as the most compatible approach to applied to internet and electronic communication. better suited to studying Internet use because users are more actively engaged communication participants in the Internet environment as compared with degrees of engagement in other traditional media (Hou, 2011). Technology acceptance model (TAM) represents another theory, first presented as a way to predict the probability of a new form of technology to be adopted within a specific group or an organization (Legris, et al., 2003). For example, Hoassain and de Silva (2009) as well as Shih (2004) have shown, using TAM, that the level of importance related to the actual information need is how the information seeker assesses the actual usefulness of the information. This concept is referred to as perceived usefulness (Hoassain & de Silva, 2009). The perceived usefulness is what contributes to the TAM mentioned by (Legris, et al., 2003). For Example, when Facebook was in transitioning from being a newly launched social network to becoming the most visited social network, outranking MySpace, there was a perceived usefulness shared by the public where a large majority of internet users perceived the information made accessible on Facebook as more valuable than of similar networks. Hossain and de Silva (2009) note that TAM impacts perceived usefulness, but it also has a significant influence on ease of use, user attitudes toward their used of the internet and the information seeking process in general. The authors note this can substantial impact the information seekers performance as they make use of whatever technological tool with which they are accessing the internet (Hossain and de Silva, 2009). The TAM, however, does have its limitations. Although it has been widely used to study user acceptance of new technologies, it does not incorporate social structure and influence as a significant factor (Hossain and de Silva, 2009). Turner, et al. (2010), in their review of literature on TAM, gathered evidence that “behavioral intent to use” is likely to be connected with actual usage. TAM’s variables perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness are less likely to be correlated with actual usage. Regardless, TAM is still a useful model which can be used in gathering policy recommendations for the use of information technology fields or in organizations that could most benefit from the model like universities or the tech industry. The conceptual framework of TAM is presented in Wilson’s work and can be seen below. The model makes use of two independent variables, specifically socio-demographic profile and perception of social media.

Fig.1.Cruz, F. & Jamias, S. (2013) Influencing factors in social media usage

The above model shows that information usefulness perception plays a substantial role in the adaptability of a certain technology and information sources.

Another model of information behavior is presented Fisher et al (2005)., who has an an information behavioral theory model that offers four select explanations that explain why individuals behave the way they do. The authors note not most people make decisions based based on the information they possess, but not necessarily all of the information that may be available. The first the authors note, 1) “in decision making, people make a good enough decision to meet their needs, and do not necessarily consider all the possible, or knowable, options” (Fisher et al., 2005, p.5). This means people mainly focus on minimum necessities. Second the authors note 2) “people underestimate the value of what they do not know, and overestimate the value of what they do know” (Fisher et al., 2005, p.5). This means that very few people are aware of just how uninformed they might be, or how they might operate given unknown information. On the other hand, information these individuals do know is given more value and worth. This is why most people don’t invest time in seeking information. Another reason why individuals tend to avoid seeking new information is noted in factor 3) “gaining new knowledge may be emotionally threatening in some cases” (Fisher et al, 2005, p.5). He justifies this concept by pointing out that most people base their perceived identity on the body of knowledge they posses, and changing this knowledge can poses a threat to one’s sense of self. The final factor in Fishers model of individual information behavior is the fact that 4) “information is not tangible” but objects are tangible.

In Case’s (2007), “Looking for information: A survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior” Case defines information as any difference one perceives in their environment, or any aspect one notices in the pattern of their reality. Case bases the foundation of his study on three core principles about information.

- “An information need is a recognition that your knowledge is inadequate to satisfy a goal that you have”(Case, 2007,p.5).

In this respect Case touches on cognitive need. He points out that one knows they have an information need when the information they have access t is not proficient enough to satisfy their thirst for knowledge.

- “Information seeking is a conscious effort to acquire information in response to a need or gap in your knowledge” (Case, 2007,p.5).

As the gap in knowledge creates a wanting that must be fulfilled, Case points out that this information need is a constant need that requires continuous pursuit. This is how he defines information seeking.

- “Information behavior (hereafter,“IB”) encompasses information seeking as well as the totality of other unintentional or passive behaviors (such as glimpsing or encountering information), as well as purposive behaviors that do not involve seeking, such as actively avoiding information” (Case, 2007,p.5).

The most commonly discussed aspect of information science, specifically in regards to the acquisition of information is information seeking. Information seeking does not occur until pressure is applied to a situation in which an information need merges. It is a behavior so commonplace that it is generally not an object of concern until time pressure makes it one. If one is in the process of making an important decision, for example making a major purchase or trying to finish a task by a critical deadline, it can present an environment for substantial information need. As one attempts to seek out new information, they might find themselves searching online or even asking others for assistance. Case notes that, “we may do everything we can to satisfy our desire for input, until either our need is satisfied or we have run out of time. More commonly, it is the latter, as the demand for “information” is usually elastic—there is always more that one could know” (Case, 2007,p.5). He further points out that once one’s need is satisfied, or the seeker gives up the search for information, they tend to return to a passive state of information seeking (Case, 2007).

Ian Ruthven and Diane Kelly’s (2011) text “Interactive Information Seeking Behavior and Retrieval” is considered one of the standard texts in information science, especially in regards to information retrieval (IR). It’s also a valuable source of research in regards to human factors within information retrieval (IR). This entails the context of information, the representation and structure of that information, retrieval interaction, information behavior, and multi-media and web-based information. Bärisch (2008) defines information retrieval (IR) as “finding material (usually documents) of an unstructured nature (usually text) that satisfies an information need from within large collections (usually stored on computers” (Bärisch, 2008, p.47). Professor Ian Ruthven, University of Strathclyde, Scotland and Associate Professor Diane Kelly, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, gather 17 highly experienced senior and younger researchers from the information industry and academia to contribute to all 13 chapters of this textbook. The main theme of the text is human and computer interaction, specifically the process of information retrieval through the use of information systems. The text reveals the importance of information interaction research and the role it plays in the web search industry. The interdisciplinary nature of information science is once again revealed through Ruthven and Kelly’s (2011) as the authors demonstrate how laboratory focused IR and user based information behavior studies correspond and supplement one another. This is an example of mixed research as the bridge connecting both qualitative based studies and quantitative data in the field of information science is examined in context. The work serves as an effective supplement to Ingwersen and Järvelin’s (2005) research monograph on IR and integration of information seeking. It does this by bringing their previous work into the context of a more modern perspective and showing the relevance of IR and information seeking as it relates to social media and web search. The first four chapters of the text focus on human information behavior and information seeking, and task-based IR interaction. The text also focuses on how one might go about doing research on these topics within the field of information research. These sections are followed up by a focus on information representation or the actual architectural structure of information in how is presented. It is at this point the authors present what they refer to as the model of four families of common retrieval, which they define as probabilistic, vector space, Boolean, language model and the labeled access model. The Boolean retrieval model is different from rank based retrieval methods like a vector space model, where the information seeker largely utilizes a free text query, by typing one or more words as opposed to using a specific language with operators for building up query expressions, and the system decides which documents best satisfy the query. Despite decades of academic research on the advantages of ranked retrieval, systems implementing the Boolean retrieval model were the main or only search option provided by large commercial information providers for three decades until the early 1990s when the world wide web was launched.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Self efficacy: towards a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215.

Bärisch, S., & Hasselbring, W. (2008). Model-Driven Test Case Construction by Domain Experts. Model-based Testing in Practice, 9.

Burnkrant, R. E. (1976). A motivational model of information processing intensity. Journal of Consumer Research, 21-30.

Case, D. O. (2007). Looking for information: A survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior (2nd ed.). Boston: Academic Press.

Cruz, F. & Jamias, S. (2013). Scientists’ use of social media: The case of researchers at the University of the Philippines Los Banos. First Monday, 18(4), Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/4296

David Ellis, Merete Haugan, (1997) Modeling the information seeking patterns of engineers and research scientists in an industrial environment, Journal of Documentation, Vol. 53 Iss:4.

Dervin, B. (1996). Chaos, order and sense-making: a proposed theory for information design. In R. Jacobson (Ed.), Information design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ellis, D. (1989). A behavioral approach to information retrieval system design. Journal of Documentation, 45(2), 171–212

Fisher, K. E., Erdelez, S., & McKechnie, L. (Eds.). (2005). Theories of information behavior. Information Today, Inc..

Hossain, L., & de Silva, A. (2009). Exploring user acceptance of technology using social networks. Journal of High Technology Management Research, 20, 1-18.

Hou, J. (2011). Uses and gratifications of social games: Blending social networking and game play. First Monday, 16(7).

Ingwersen, P., & Järvelin, K. (2006). The turn: Integration of information seeking and retrieval in context (Vol. 18). Springer.

Kelly, D., & Ruthven, I. (Eds.). (2011). Interactive Information Seeking, Behaviour and Retrieval. Facet.

Ko, H., Cho, C. H., & Roberts, M. S. (2005). Internet uses and gratifications: a structural equation model of interactive advertising. Journal of advertising,34(2), 57-70.

Rosenthal, A., Mork, P., Li, M.H., Stanford, J., Koester, D. & Reynolds, P. (2010). Cloud computing: a new business paradigm for biomedical information sharing. Journal of Biomedical Informatics.

Ruggiero, T. E. (2000). Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass communication & society, 3(1), 3-37.

Legris, P., Ingham, J., & Collerette, P. (2003). Why do people use information technology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model. Information & management, 40(3), 191-204.

Lind, A. (2009, May). Uses and gratification theory in virtual network anlysis. In Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the ISSS-2009, Brisbane, Australia(Vol. 1, No. 1).

McQuail, D. (Ed.). (1972). Sociology of mass communications: selected readings (Vol. 961). Penguin books.

Simon, S.R., Evans, J.S., Benjamin, A., Delano, D. & Bates, D.W. (2009). Patients’ attitudes toward electronic health information exchange: qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research

Shih, H. P. (2004). Extended technology acceptance model of Internet utilization behavior. Information & Management, 41(6), 719-729.

Stafford, T. F., Stafford, M. R., & Schkade, L. L. (2004). Determining uses and gratifications for the Internet. Decision Sciences, 35(2), 259-288.

Straubhaar, J., LaRose, R., & Davenport, L. (2013). Media now: Understanding media, culture, and technology. Cengage Learning.

Turner RK, Morse-Jones S, Fisher B (2010) Ecosystem valuation: a sequential decision support system and quality assessment issues. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1185:79–101

Wilson, T. D. (1981). On user studies and information needs. Journal of documentation, 37(1), 3-15.

Wilson, T. D. (1994). Information needs and uses: fifty years of progress. Fifty years of information progress: A Journal of Documentation review, 15-51.

Wilson, T. D. (1997). Information behaviour: an interdisciplinary perspective. Information processing & management, 33(4), 551-572.

Wilson, T. D. (1999a). Exploring models of information behaviour: the ‘Uncertainty’ Project. In T. D. Wilson & D. K. Allen (Eds.), Exploring the contexts of information behaviour: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Seeking in Context, August 12-15, 1998. Sheffield, UK.

Wilson, T. D. (1999b). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249-270.

Wilson, T. D., Ford, N. J., Ellis, D., Foster, A., & Spink, A. (2002). Information seeking and mediated searching. Part 2. Uncertainty and its correlates. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee