Delegation and Engagement: Pathways to Organizational Change, Essay Example

Introduction

All-4-One is an organization with a great deal going for it, but with some significant organizational problems as well. Of the various issues the organization must confront, issues pertaining to motivation, leadership, and organizational culture appear to be the most salient from a management perspective. Increasing the performance of All-4-One will necessitate significant reforms, largely pertaining to leadership style and how to engage the employees in organizational processes.

Motivation

Motivation is one problem that All-4-One appears to be having. Significantly, monetary incentives account for the majority of positive motivators. Here, a key insight is that money, and the satisfaction of physical needs and personal desires that it can bring, is not the only thing that can motivate people. Following Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs, beyond basic needs, humans have social needs for belonging, and ego or self-esteem needs, needs to achieve personal goals and maintain a certain self-image (Mullins 2010, p. 259; Wlodarczyk 2011, pp. 17-18). Therefore, following Maslow’s model, it should be possible to motivate employees by engaging them socially and/or in terms of personal aspirations.

A particularly famous study of job satisfaction both supports and expands upon some of Maslow’s ideas. In his survey of 200 accountants and engineers, Herzberg discovered satisfied and dissatisfied workers identified different factors as the cause of their respective feelings about the workplace. Herzberg found that dissatisfaction is dependent upon hygiene factors, such as pay and working conditions, job security and status (Madura 2007, pp. 367-368; Pride, Hughes & Kapoor 2012, p. 302). Employees who perceive the levels of these hygiene factors as inadequate will be dissatisfied. On the other hand, employees who are satisfied are responding to motivational factors, such as achievement, responsibility, recognition, advancement, and growth (Madura 2007, pp. 367-368).

The question then becomes, How should All-4-One use these insights to devise practical strategies for motivating its employees? Amabile and Kramer (2011) suggest a powerful strategy: give employees a sense of their own progress, one small milestone at a time. The concept is elegantly simple and powerful: what truly motivates people “is the sense that they are making progress” (p. 73). Two other aspects of work life were present as well: catalysts, work-promoting actions that facilitated task completion, and so-called ‘nourishers’, i.e. encouragement, recognition, and respect (p. 73). Days on which employees felt that they made progress, felt that their work was supported by some process in the workplace, and felt that their efforts were recognized and genuinely appreciated emerged as the best days (p. 73).

With a better leadership structure, All-4-One would be better organized to both communicate to employees what they need to be doing, and to reward them with praise and affirmation for succeeding in the achievement of each small milestone (Amabile & Kramer 2011, pp. 74-75). All-4-One needs to set very clear, small milestones toward its goals, and its goals need to be clearly defined in turn. The company also needs to ensure that it is supportive of autonomy, something that would probably be greatly facilitated by delegating authority to team leaders and to individual employees instead of the owner retaining a more centralized control of the entire operation (pp. 75-76).

In a study of federal workers, Frick and Drucker (2011) studied the respective causes of motivation and dissatisfaction. Their findings dovetailed with the findings of Herzberg, as well as Amabile and Kramer. Rather than monetary rewards, the factors that the employees consistently ranked as the most important for motivation were intangible: “meaningful work, belief in mission, sense of public service, opportunity to advance, and relationship with coworkers” were the top five, for example (p. 381). Other high-ranking factors were similarly intangible and focused on affect. Time and again, the most important factors for motivation were intrinsic. By comparison, the most important factors contributing to dissatisfaction were far more extrinsic, and largely had to do with resources, support, and the like (p. 381).

All-4-One does not appear to have problems with high dissatisfaction, which already puts it ahead in some ways. Clearly, what the owner needs to do is instill in her employees a sense that they are doing meaningful work, work that truly matters. They need a better sense of mission. They need to be encouraged to take pride in delivering good customer service, something which can be a trying experience in a call center. And they need opportunities to advance in the company, as well as meaningful relationships with their coworkers. The creation of teams with leaders might facilitate both of these ends quite handily.

Leadership

Part of All-4-One’s motivation problem, then, is a leadership problem. Some of the earliest theories of leadership were the trait approaches. The concept of leadership promoted by the trait theories is that leaders are born, not made. Leadership, the argument goes, depends on a number of personality traits, for example confidence, dominant behaviors, a high energy level, persuasiveness, and the like. This trait theory approach underlay an entire school of thought in the historical discipline, the ‘Great Man’ theory of history. The argument was that history was driven by exceptional individuals who emerged to seize the reins, driven by their own force of will (Lussier & Achua 2013, p. 19; Northouse 2013, p. 7).

The behavioral approach emerged next, seeking to explain leadership in terms of the behaviors that leaders actually displayed. Leadership, this approach argued, could be learned. Using this approach, behavioral researchers were able to identify two main styles of leadership: task-oriented and people-oriented (Lussier & Achua 2013, p. 20). The behavioral approach lost dominance in the 1960s, with the growing recognition that no one behavioral style was best for all leaders in all situations. Its insights, however, continue to inform more modern paradigms of leadership, such as contingency leadership theory (p. 20).

Contingency leadership theories are highly situational and context-specific. Unlike the trait and behavioral approaches, they consider the specific variables: who is the leader, who are the subordinates, and what is the situation? All of this will matter in determining how the leader should lead (Lussier & Achua 2013, p. 20). One key variable here which is especially relevant to All-4-One’s current dilemma about team leaders is the difference between assigned and emergent leadership: the owner is seeking to assign leaders to teams, which means that those leaders will then have to accustom themselves to command (Northouse 2013, p. 8).

One way the owner could make a more informed decision would be to survey the teams and ask them how they do things: what works, what doesn’t, and who does what. If the owner makes it clear to them that she is trying to make sure the organization is being run effectively as much for their own well-being as anything else, in the interests of making a better work environment, she is likely to get better, fuller, and more honest answers. From there, the owner can ascertain whether she might actually have some emergent leaders—or potential emergent leaders—for at least some of the teams, or if she needs to assign leaders to all teams.

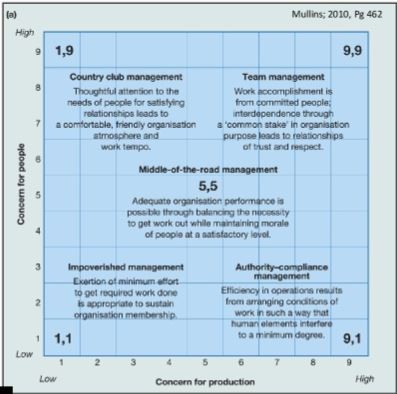

Drawing on the insights of contingency and behavioral theorists, Blake and Mouton argued that all leadership styles can be characterized in terms of how they answer two very basic, very fundamental questions: “How important is the production of results by the group?”, and secondly, “How important are the feelings of group members?” (Forsyth 2010, p. 269). This, of course, harks back to the difference between task-oriented and people-oriented leadership, but it also recognizes that the two are not necessarily dichotomous: caring that much more about results does not have to come at the expense of caring that much less about people, and vice-versa. Blake and Mouton represented these differences by assigning them values from 1 (low importance) to 9 (very high importance) on a grid with two axes, one for people and the other for production (p. 269).

First, there is the impoverished leader, who scores 1,1: such a leader does not assign much importance to people or to productivity (Forsyth 2010, p. 269). On the other hand, a 9,1 leader has the maximum concern for production, but the minimum for employees. The 1,9 leader is completely the opposite, caring greatly for people and the mere minimum for production. A 9,9 leader cares greatly about people and production both, and is likely to address the needs of both through interdependence (pp. 269-270). There is also the middle-of-the-road leader, who scores 5,5: such a leader devotes moderate or adequate concern to both elements, and is likely to achieve middle-of-the-road results for both (p. 270).

There is another way, however, to conceptualize the process of leadership—as a dynamic process, rather than only as something that the leader practices, or exercises. This is the central premise of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory. LMX theory examines the relationship between supervisor and subordinate, seeking to ascertain the quality of the interactions between the two. A high-quality LMX dyad is one characterized by a certain amount of mutual control, as the subordinate is able to influence the supervisor to some degree as well. Such a relationship is one characterized by respect, acceptance, and support: the subordinate follows the supervisor not simply because they have to, not simply as a matter of carrying out orders, but because they understand that the tasks in question need to be done, and they have genuine respect for their leader (Borchgrevink 2004, pp. 100-101; Forsyth 2010, p. 271).

From the perspective of LMX theory, individuals do not all respond to the leader in the same way. Some individuals have a much better ‘fit’ with the leader, and they form a subgroup known as the inner group, or ingroup. They have higher-quality linkages with the leader, in that leaders work more closely with them, take their opinions more seriously, and support them more. The second group, the outgroup, do not have such high-quality linkages. They may still be productive, but they are usually less productive than the ingroup, and they are certainly less loyal. The challenge for the leader, then, is to recruit as many people to the ingroup as possible (Forsyth 2010, p. 271).

How to do this? Ibarra and Hansen (2011) explain that one of the best strategies is soliciting employee participation. Take the example of the candidate who felt she didn’t understand the mentality of some of the people on other teams. A leader looks at this as a challenge, one that they will address by seeking the participation of team members. A good way to do this is to sit down with the team, as a group and, if necessary, individually, and ask them about what they think of current business operations. This is part of being a connector between people (pp. 69-71). Another aspect of truly soliciting employee participation is engaging employee talent: leaders should seek out employee insights, and ask employees about the informal processes that they have developed for completing tasks in the workplace (pp. 71-72).

The owner also needs to be on guard against picking the wrong leaders, based on the ‘halo effect.’ Fundamentally, the halo effect is an illusion produced by only focusing on certain, generally positive, aspects of performance. This is true for leaders and for performance alike: when things are going well with a company, or when a leader (or prospective leader) manifests successful behavior, it is easy to both overlook things that are not working or might prove to be less successful, and to assume that some things have stopped working or did go wrong in the event that the company, or the leader, suffers a reverse (Rosenzweig 2007, pp. 6-7; Sorcher & Brant 2002, pp. 78-80).

Organizational Culture

Another issue, or set of issues, that All-4-One must confront concerns organizational culture and organization change, which is to say organization development. First and foremost, it is essential that the owner not seek to change the organizational culture in ways that would actually harm employee morale and productivity—the two being frequently interdependent. All-4-One might, indeed, benefit from a more formal organizational culture, but whatever she does, the owner must ensure that she still promotes an organizational culture that empowers employees to participate in decision-making, share information, and interact with each other in positive ways (Spreitzer & Porath 2012, pp. 94-98; Ye 2012, pp. 90-91). It is particularly important to point out that a fun-loving, informal organizational culture is not incompatible with superlative performance: indeed, the case of Southwest Airlines establishes that it may promote such outstanding performance (Spreitzer & Porath 2012, p. 95).

The other thing that the owner and her team leaders positively must do is seek to understand the organizational culture before they try to change it at all. This is not to suggest that they will not find areas in which it could be improved, only that they should understand what they are working with before they attempt to change it in any way. Observing employees and asking them questions about practices, procedures, and interactions with others is a good way to go about this. It is important to identify the values of the culture, implicit as well as stated, and the same for the rules. Only by so doing is it possible to truly begin to understand the culture (Schein 2010, pp. 177-178).

Assuming the owner has run through this process and has concluded that the organization would, indeed, benefit from certain changes, she can begin to implement them. First and foremost, she must establish an atmosphere of trust. It is important for her to allay the inevitable concerns and fears that the employees will have about this culture change. They need to understand exactly what needs to change, why, what will and will not be expected of them, and that they are important and valued members of the whole process (Schein 2010, p. 304). If they are afraid of appearing incompetent, or of running afoul of stricter policies, or of their workplace environment becoming an unpleasant place, they will not give it their all. Fundamentally, the employees need to be involved in the changes as active change partners, members in the cultural shift. This may require training them to perform certain processes and procedures in a somewhat different way. It will certainly require listening to their concerns, taking the time to address feedback, and being flexible enough to modify aspects of the planned outcome that simply prove unworkable and unrealistic (pp. 304-306).

Maintaining an atmosphere of positive emotions is essential throughout this process. It sounds like All-4-One already has this, which is a key asset. Maintaining this during the course of the change will require the owner and the other leaders to take it upon themselves to make very real efforts to include the employees in the new roles and responsibilities of the organization. In other words, if the owner wants a successful culture change, and for the organization to perform even better than it is now, then she must be prepared to delegate authority and empower the employees, not simply establish stricter rules for behavior and expect them to follow orders (Vacharkulksemsuk, Sekerka & Frederickson 2011, pp. 101-103; Ye 2012, pp. 90-91). With proper support for employees and a willingness to empower them, it can, indeed, be perfectly feasible and even optimal to set higher expectations for them, expectations that will help to produce a more formal and more productive organizational culture—if such would, indeed, constitute an improvement in this case, which is not a given.

Conclusion

All-4-One has been growing successfully, and it has an organizational culture which appears to have many strengths. The fundamental problems have everything to do with the owner’s leadership style. She has been relying on monetary incentives to motivate employees, when all that is needed is proper engagement. By involving the employees to a considerably greater degree in making the decisions that define the running of the organization, the owner of All-4-One could greatly improve performance. The organizational culture would change as a result of this. Such processes might also be used to encourage development of a more formal organizational culture as well. If provided with sufficient autonomy and support, employees can rise to higher expectations.

References

Amabile, T, & Kramer, S 2011, ‘The power of small wins’, Harvard Business Review, 89, 5, pp. 70-80.

Borchgrevink, C P 2004, ‘Leader-member exchange in a total service industry: The hospitality business’, in Graen GB (ed.), New frontiers of leadership, Information Age Publishing, Charlotte, pp. 99-120.

Forsyth, D 2010, Group dynamics, 5th edn, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, Belmont.

Frick, D, & Drucker, P 2011, ‘Motivating the knowledge worker (cover story)’, Defense Acquisition Research Journal: A Publication of the Defense Acquisition University, 18, 4, pp. 368-387.

Ibarra, H, & Hansen, M N.D., ‘Are you a collaborative leader?’, Harvard Business Review, 89, 7-8, pp. 66-74.

Lussier, R & Achua, C 2013, Leadership: Theory, application, & skill development, 5th edn, South-Western, Mason.

Madura, J 2007, Introduction to business, 4th edn, Thomson Higher Education, Mason.

Mullins, L (2010), Management & organisational behaviour, 9th edn, Pearson Education Limited, Essex.

Northouse, PG 2013, Leadership: Theory and practice, 6th edn, SAGE, Thousand Oaks.

Pride, W, Hughes, R & Kapoor, J 2012, Business, 11th edn, South-Western, Mason.

Rosenzweig, P 2007, ‘By invitation: The halo effect, and other managerial delusions’, McKinsey Quarterly, 1, pp. 76-85.

Schein, EH 2010, Organizational culture and leadership, 4th edn, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Sorcher, M, & Brant, J 2002, ‘Are you picking the right leaders?’, Harvard Business Review, 80, 2, pp. 78-85

Spreitzer, G, & Porath, C 2012, ‘Creating sustainable performance (cover story)’, Harvard Business Review, 90, 1/2, pp. 92-99.

Vacharkulkemsuk, T, Sekerka, LE, & Frederickson, BL 2011, ‘Establishing a positive emotional climate to create 21st-century organizational change’, in Ashkanasy NM, Wilderom CPM, & Peterson MF (eds.), The handbook of organizational culture and climate, 2nd edn, SAGE, Thousand Oaks, pp. 101-118.

Wlodarczyk, AZ 2011, Work motivation: A systemic framework for a multilevel strategy, AuthorHouse, Bloomington.

Ye, J 2012, ‘7 principles for employee empowerment’, Seri Quarterly, 5, 4, pp. 90-93

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee