Developing Information Literacy in South East Asia, Thesis Example

Abstract

Access to information, and the knowledge of how to use it, are the cornerstones of successful and sustainable growth in the developing world. This paper examines the role of public libraries in developing nations in South East Asia in promoting Information Literacy, with an emphasis on the strengths and weaknesses of the current condition as well as recommendations for improvement s suggested by organizations such as the United Nations Education, Science, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Introduction

“Libraries remain the meccas of self-help, the most open of open universities … where there are no entrance exams and no diplomas, and where one can enter at any age.”

– Former Librarian of Congress Daniel J. Boorstin, 1984

The American Library Association defines “Information Literacy” as “a set of abilities requiring individuals to recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information” (ACRL, 2012). Access to information for all citizens is a core concept in democratic society, and Information Literacy is a vital component of successful and sustainable democratic societies in both the modern and developing worlds. In many parts of the world, such as developing nations throughout Asia, libraries are sub-par by Western standards. It is imperative that the leaders of developing nations establish Information Literacy programs to help ensure long-term sustainability and economic growth, and public libraries are the foundation on which Information Literacy is built.

Discussion

The concept of Information Literacy was first brought to the attention of the general public in 1974, when Paul Zurkowski, then-president of the U.S. Information Industry Association, published a proposal recommending that the National Commission on Libraries and Information Science establish a program promoting universal standards for Information Literacy (Wiley, 2010). According to Zurkowski, “people trained in the application of information resources to their work can be called information literates. They have learned techniques and skills for utilizing the wide range of information tools as well as primary sources in moulding information solutions to their problems.” As technology advances, and the ways in which people access information changes, it is increasingly important that libraries respond to these changes in dynamic, pro-active ways.

The significance of the role that libraries (and librarians) play in the community cannot be overstated. Libraries function as a way of building community through shared information, and it is increasingly important that they play an active role in reaching out to the community. Librarians are expected to develop the kind of managerial skills that foster such community outreach, and must find ways to foster Information Literacy in their communities (Wiley, 2010). If an informed populace is the foundation of democratic society, then the library is the foundation of that informed populace. Developing nations must do all they can to cultivate Information Literacy in their citizenry, and libraries are the most important institutions for such cultivation.

For many people throughout the world, their first (and sometimes only) exposure to libraries is in schools. Most schools have at least some form of library, whether it is simply a meager collection of books or a full-blown library with books, periodicals, audio-visual materials, and access to the Internet and other forms of electronic information-access. It is in the context of school libraries, especially at the primary-school level, that students must be taught not only how and where to access information, but also how to differentiate between useful, accurate information and material that is inaccurate or otherwise unneeded, incorrect, or inappropriate. Library users, in learning how to discern between useful information and non-useful information, become “wise consumers of information” (Wiley, 2010). In the modern age of information overload through the media and the Internet, it is more important than ever that Information Literacy is allowed to flourish.

In 2003 the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) launched a joint project known as “Development of Information Literacy in South East Asian Countries.” This project was intended to assess the state of Information Literacy in the participating nations and to recommend action plans for government agencies, libraries, educational institutions, and other organizations to promote the development of Information Literacy (UNESCO, 2005). The team behind the project gathered extensive information from various participants, from school teachers to university librarians to government officials, and used that data to develop recommendations for how school libraries could use available resources to further the cause o Information Literacy in their schools and communities.

The first stage of the project began with surveys, conducted in person, through the mail, or electronically. Among the questions asked in the survey was one about the concept of Information Literacy, and what it meant to each respondent. The project team members found that the idea of Information Literacy meant many different things to different respondents, and the team determined that fostering the use of a general, universal standard definition for Information Literacy was one of the first recommendations they would have to make. They also discovered that school teachers and school librarians often displayed what the team considered to be outmoded and outdated ideas about what role libraries and librarians could and should play in the community. As the team saw it, these outmoded ideas were, in many cases, remnants of the colonial era, when the development of public education systems was often intended to cultivate a populace whose primary role in life was to maintain subservience to their colonizers.

The team also found that, in many instances, the training that librarians and teachers received about Information Literacy and Library Sciences was inadequate, or even non-existent. Roughly 40% of the schools in one of the targeted South East Asia countries had no libraries at all, and in those that did, there was often no cohesive leadership where Information Literacy and Library Sciences were concerned (Sing et al, 2005). Those schools and libraries that did promote the development of Information Literacy often did so in disparate ways; in some schools the teaching of IL was part of a standard curriculum while in others it was extra-curricular and only available to or accessed by a limited number of students.

The project team found a range of specific inadequacies throughout the school libraries of South East Asian countries. Many libraries had a limited number of books, and a significant number of them had limited or no access to computers or the Internet. In many cases schools that did have computers did not incorporate them into their library systems; they were instead set up in computer-lab settings, and only certain students could access them. The team also found that Internet connectivity was spotty in many parts of South East Asia, so even those schools that did have computers did not always have access to the Internet. Many of the school systems throughout South East Asia demonstrated a lack of uniformity and standardization; some schools were funded by local or national governments, while others were paid for by private citizens or other local-community resources. Schools in the region often had to rely on donations of funding and equipment in order to develop computer labs and electronic information access in their schools and libraries (Dorner & Gorman, 2011).

The most significant and pervasive problem uncovered by the team was a lack of adequate staffing, and a lack of adequate training for the staff that did exist. Many schools did not have full-time librarians; others had no librarians at all, and relied on teachers to devote part of their time to staffing and maintain school libraries. In those cases, especially, the part-time librarians and the teachers that were tasked with the dual roles of educating students and staffing libraries had little or no instruction library sciences and Information Literacy. The report from the Information Literacy project described the situation in many South East Asian schools and libraries as “grim,” noting that the combined factors of inadequate resources, inadequate staff, and inadequate training meant that a significant number of schools and libraries were not equipped to foster the development of Information Literacy in the their students and their communities (Singh et al, 2005).

After amassing the information acquired from their surveys and studies, the team developed a series of formal and informal recommendations for improving the school libraries in South East Asian countries. Among the informal recommendations were that schools prioritize reading and writing among students, and develop ways that these tasks could be incorporated with and take advantage of school libraries. Another suggestion was that, where possible, school libraries be made available to the community at large, especially in those areas where no other public libraries existed. Each of these recommendations were intended to foster a better understanding of and consideration for the value and importance of libraries within the community; in this way, the team hoped, the community might become more proactive in developing and strengthening their school libraries.

The first of the formal recommendations made by the project team was the adoption of a standard definition of Information Literacy throughout all schools in the study region. The project team offered the following definition of Information Literacy:

Information literacy is the ability to recognize when information is needed, to identify the needed information, to identify the sources, to locate and access information efficiently and effectively, to evaluate information critically, to organize and integrate information into existing knowledge, to use information ethically and legally, to communicate information , and carry out all of the above activities effectively. (Singh et al, 2005).

This standard definition, it was asserted, would make it easier to promote the idea of Information Literacy throughout the region, while also encouraging the utilization of shared information, resources, and ideas among participating schools both within specific countries and across national borders. The project team recommended that, where possible and appropriate, schools join forces to combine their strengths and alleviate their weaknesses. Those schools with inadequate libraries, for example, could be allowed to borrow materials from better-stocked libraries; in other cases, understaffed libraries could host visiting librarians who would offer advice, training, and other assistance to school staffers who were called upon to work both as teachers and as part-time librarians.

The UNESCO/IFL project also recommended action plans that UNESCO and IFLAA could undertake to help spread the growth of Information Literacy in South East Asian countries. The team encouraged the use of UNSECO and IFLA financial resources to develop media campaign intended to raise awareness about the importance of Information Literacy and to fund training programs that could be accessed by teachers and librarians from participating nations. The team further recommended that UNESCO and IFLA develop outreach programs intended to target various organizations responsible for education and Information Literacy in the participating nations. These outreach efforts included plans for lobbying government officials and organizations to develop their own Information Literacy programs; other plans were developed to foster awareness of and interest in Information Literacy at higher educational institutions, such as high schools and universities. These plans were intended not only to encourage the addition of Information Literacy programs in high school and university curriculums, but also to encourage these institutions to develop programs aimed at promoting Library Sciences as academic and professional career choices.

A range of other programs and plans were proposed, some of which were not as general, but were instead aimed at specific countries, and regions within different countries. In the cases of these more specific projects, many were designed with an understanding that social, economic, cultural, and political differences between and among different regions required different approaches to solving the problem of inadequate Information Literacy programs (Singh et al, 2005; Dorner & Gorman, 2006). The team recognized that libraries are more than just storehouses of information, and that a functional library system plays an important civic and cultural role in the community. In those areas that were particularly hard-hit economically, libraries were often the only sources of information in the community; as such, these libraries, the team asserted, had a responsibility to do all they could to foster cultural and intellectual enrichment in the community .

As an adjunct to the idea of making school libraries available to the general public, the project team offered suggestions about specific programs aimed at fostering community interest and involvement in the libraries. One of the most significant actions the libraries could take, it was suggested, was the development of adult-literacy programs. In many regions that have been historically underserved by libraries, and educational systems in general, adult literacy is woefully low. By providing access to reading materials and instruction, it was felt, school libraries could help to improve the overall community by advancing the cause of adult literacy. This suggestion goes back to the core concept that an informed populace is the foundation of democratic society (Lau, 2006).

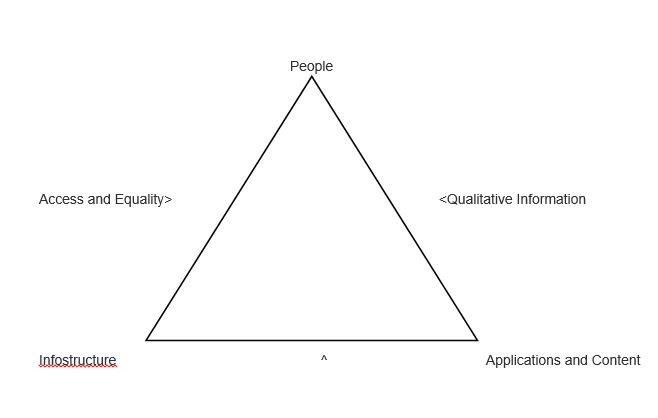

Not every Asian nation is lacking in efforts to develop Information Literacy, of course. Malaysia serves as an example of a nation that has made Information Literacy a national priority. In 1996 the Malaysian government established a program called the “National Information Technology Agenda (NITA); the stated purpose of NITA is to “transform the entire Malaysian society into an information-based society, then to a knowledge-based society, and finally to a values-based knowledge society” (Edzan, 2008) The NITA protocols place a clear emphasis on the role and significance of Information Literacy in civic, cultural, and economic development, and focus on ways that the nation can maintain sustainable development in an increasingly technology- and information-based global community. NITA has proposed a pyramidal figure representing the components and priorities of their program, seen below:

At the top of the pyramid are “people,” with “infostructure” and “Applications and Content” at the other corners (Edzan, 2008). Along the sides of the pyramid are the supporting concepts of “Access and Equality,” “Qualitative Information,” and Creating Value,” all of which are intended to demonstrate the interconnectivity of the ideas and values that comprise the NITA program (Edzan, 2008). The NITA protocols call for a national standard for Information Literacy, and set the year 2020 as the target date by which all citizens of Malaysia will meet these national standards (Edzan, 2008). In order to ensure that these goals are met, the Malaysian government has made Information Literacy a national priority at al educational levels, beginning in elementary schools and extending through high school and university levels. The government has placed a priority on developing so-called “infostructure,” which refers both to IT hardware-infrastructure and the development of content and information databases and access, with the goal of making this infostructure available to all Malaysians (Edzan, 2008).

Conclusion

In the modern age, advancing the cause of Information Literacy is imperative for several reasons. The advent of the Internet and other forms of digital communication have made access to information easier and faster than ever before, and the global economic system has grown around these developments. Those nations which have embraced these technological advances have been the ones to flourish economically in the 21st Century, and those nations that are lacking in Information Literacy and access to technology and information are at a clear disadvantage on the global stage.

It is not just economics that drives the need for global development of Information Literacy, however. As nations throughout the developing world move towards ever-increasing freedom and democratization, the need for access to information –and the need to understand how to use that information- become increasingly important. A well-informed populace is a vital component of a democratic society, and the world offers many examples of nations (such as North Korea) that are lacking both in Information Literacy and in economic development (Peng, 1991). It is clear that Information Literacy is mandatory for those nations that wish to flourish domestically and compete on the global level, and it is clear that publicly-accessible libraries serve as the cornerstone of the development of Information Literacy. For nations throughout South East Asia, and all parts of the developing world, the future begins at the local library.

Bibliography

ACRL (Association of College and Research Libraries). Information literacy competency standards for higher education. 2012. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency

Dorner, Daniel G.; Gorman, G.E. Contextual factors affecting learning in Laos and the implications for information literacy education. Information Research 16(2): June 2011

Dorner, Daniel G.; Gorman, G.E. Information literacy education in Asian developing countries: cultural factors affecting curriculum development and programme delivery. Submitted to Victorian Univesrory of Wellington. 23 June 2006.

Edzan, N.N. Information literacy development in Malaysia: a review. Libri, 58. 265–280 (2008).

Lau, Jesus. Guidelines for information literacy for lifelong learning. Submitted to Universidad Veracruzana 29 july 2006.

Peng, Samuel S. The public library: a major community resource for achieving the nation’s goals. The School Community Journal, 1(2) Fall/Winter l991.

Singh, Diljit et al. Development of information literacy through school libraries in South East Asian countries. UNESCO Report 2005.

Wiley, John Michael. Libraries and sustainability in developing countries: leadership models based on three successful organizations. Collaborative Librarianship 2(2): 65-73 (2010)

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee