Diabetes Coalition Field Survey, Research Paper Example

Introduction

Diabetes is a serious chronic, potentially debilitating, lifelong condition that is caused by either excessive levels of glucose (sugar) in the bloodstream (ADA, 2012). The imbalance in the body’s glucose levels in diabetics is caused by body’s inability to produce any or enough insulin and this causes elevated levels of glucose in the blood (Nguyen, Varney, Harrison, & Morahan, 2013). Millions of people, including children, are diagnosed as diabetics, which necessitates outreach programs geared towards helping to prevent diabetes through education (Aly, et al., 2006; Vable, et al., 2011). Such initiatives are also designed to help those already diagnosed with diabetes gain access to services that will help them manage their disease. However, there can be numerous obstacles that impede diabetic coalitions from achieving their outreach goals. The purpose of this brief research is to investigate possible problems in team collaboration as perceived by the coalition members through a field survey analysis of a representative sample of members of a coalition/taskforce working on the health issue.

Specific Aims & Hypotheses

The specific aim of the survey is to determine coalition member’s perceptions of possible problems in team collaboration that could or does impede the achievement of the program’s mission. Guiding the research is the hypothesis that hindrances such as lack of qualified volunteers, inadequate funding, and insufficient cohesion between intended goals and planning. This hypothesis is easily researched due to the wealth of available documented resources that cover the factors delineated. They can also be tested by interviewing coalition representatives using questions that are specific in regards to the factors mentioned. The specificity of the topic can provide new information that can help improve outcomes for diabetes patients through enhanced program measures that ensure the ability of the coalition to achieve the organizational goals (Creswell, 2009).

Background & Significance

There are many factors that can predispose an individual or make them susceptible to developing diabetes, which includes age, ethnicity, lack of proper exercise, and unhealthy eating or recreational habits (Nguyen, Varney, Harrison, & Morahan, 2013). These factors have been identified as key elements that need to be addressed in the prevention and management of diabetes. Ethnic groups such as African-Americans, Native Americans, Asian Americans, Latinos, Native Hawaiians, and other Pacific Islanders are several ethnic groups that are noted to have increased propensities for developing diabetes (ADA, 2012). There are numerous “…independent, volunteer organization consisting of individuals and agencies dedicated to the prevention, recognition, and reduction of the adverse personal and public impact of diabetes” and, due to budgetary restrictions, many of these agencies rely on volunteers to staff their organization with only a few individuals on dedicated payroll (DCC, 2014). These coalition agencies are typically rely on the support of “representatives from the general public, local health departments, universities, insurance and pharmaceutical companies, and a variety of community-based, voluntary, health and professional organizations” in order to carry out their community outreach activities (DCC, 2014).

Although it is the intention of the coalition to endeavor to meet the organizational goals by working to “…increase awareness of diabetes and advocate for programs that improve access to care, treatment, and outcomes for people with diabetes and those at risk for developing diabetes,” attaining these goals requires the collaboration of competent, capable, and qualified individuals that can organize the necessary campaigns (DCC, 2014). However, the coalitions are not always able to meet their goals and there are still many individuals in at-risk demographic group that remain unaware of their susceptibility to the disease and this reality has many aspects that are relative to the capabilities of the volunteers and the leadership presented during the campaigns. Understanding the contributing factors to the problems facing the diabetes coalitions will allow the staff to devise new policies and routines that will address the issues hindering the progress of the organization present valuable implications for policy and procedure.

Theoretical/Conceptual Framework

The theoretical framework may range across a number of disciplines and approaches in order to construct a clear connecting thread to understand whether the research hypothesis is valid. Therefore, this research will adapt an epistemological approach to gather and interpret the research data. Epistemology defines the kind of human understanding and knowledge that may be gotten through various inquiries and alternative investigation methods (Creswell, 2009). The epistemological assumptions indicate the perspective of the role of the researcher in the acquisition of knowledge. The methodological assumptions dictate what the process of research is as well as the grounds for its knowledge. Experimenter preferences, which are sampling bias and subject bias, are the major foundations of objectivity that may essentially interfere with precise investigational outcomes (Creswell, 2009). Ontology addresses what exists in a certain world; something that can be discussed. It is ideally an area in philosophy which deals with articulating the structure and nature of the universe. This can be used to refer to terms and their definitions linked to a description of a world or a problem in question. In this analysis, the ontological assumptions will be that there is a linear relationship between the available volunteers and the ability of the diabetes coalition to and the types of outcomes obtainable for their various outreach programs.

Research Design

The quantitative research methodology employs a systemic process that utilizes various techniques to gather quantifiable data for the development of new information about phenomena to probe possible relationships (Creswell, 2009). The prescribed research methodology also uses deductive approaches that proceed along a linear path, which emphasizes the explicit standardized procedures used to measure variables and test hypotheses that form plausible relationships (Babbie, 2007). Quantitative research is a methodical and experiential approach that tries to simplify resuming outcomes of other contexts to gain a deeper understanding of particular cases and contexts (Creswell, 2009).

Justification

Objectivity in research is mandatory and the quantitative method enables the researcher to gather personal and specific details objectively (Babbie, 2007). Additionally, the quantitative approach necessitates the examination of multiple variables (Creswell, 2009). The use of the quantitative research method with a survey questionnaire to gather information from volunteers, including demographic characteristics, organizational culture, organizational practices, organizational networks, mentoring and role modeling, and other details is a specific benefit o thr quantitative research method (Draugalis, Coons, & Plaza, 2008).

Method of Data Collection

This research will collect the data through an internet-based survey, presented in Appendix A: Survey Questions, which will include ten participants that work for a diabetes coalition. The survey will provide a peripheral perspective regarding the nature of the obstacles faced by diabetes coalitions. Participants will provide their input through surveys based on questions designed to gain the most accurate estimation of how the volunteers and collaboration within the organization impact outcomes and the degree of relevance for these correlational factors (Draugalis, Coons, & Plaza, 2008).

Data Collection Instrument

Data would be collected via survey that asked ten specific questions about the volunteers, the nature of the organization’s operations, the effectiveness of the campaigns, and the perceived challenges in achieving the organizational goals. These questions were based on an analysis of existing research. The survey participants were recruited via telephone and e-mail to the target diabetes coalition. The participants were recruited through a voluntary process so that the details provided would be honest and reliable. Data will be coded and analyzed through descriptive and graphical depictions.

Ethical Issues

In order not violate the ethical considerations of the respondents; all were fully informed by written forms of their right to refuse to take their survey as well as their right to withdraw their consent to participate any time before, during, or after completion of the survey. All participants were well informed of what was required of them, how the information was going to be used, and that all the information given was going to be treated with care to protect their privacy. It was also explained that the survey was completely anonymous and neither the name of the organization or the participant would in any manner be used or revealed. The respondent were asked to sign the bottom of the survey form in the provided space as a form of consent showing that they agreed to provide the information at their own free will.

Results

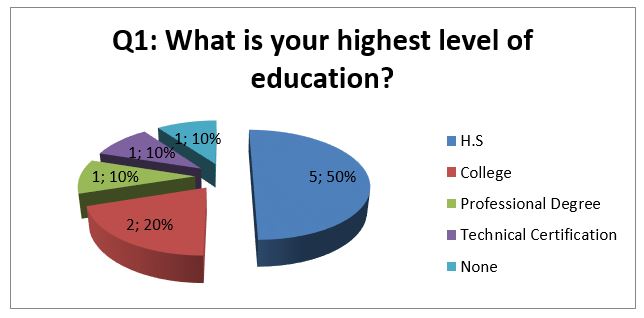

The results of the survey demonstrated that the surveyed coalition was primarily staffed by volunteers that only had a high school education, as shown in Figure 1: Educational Background of Coalition Workers, which shows that 50% of the individuals surveyed had high school education levels while only 20% had completed college and 10% had either technical or professional credentials, respectively.

Figure 1: Educational Background of Coalition Workers

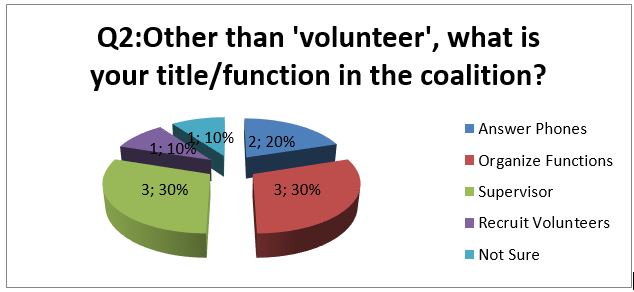

Furthermore, the analysis in Figure 2: Coalition Worker Job Description shown below, 10% of the workers surveyed indicated they were ‘Not Sure’ what their role was as a diabetes coalition employee/volunteer while 30% indicated that they were in a supervisory role or in charge of organizing functions, respectively.

Figure 2: Coalition Worker Job Description

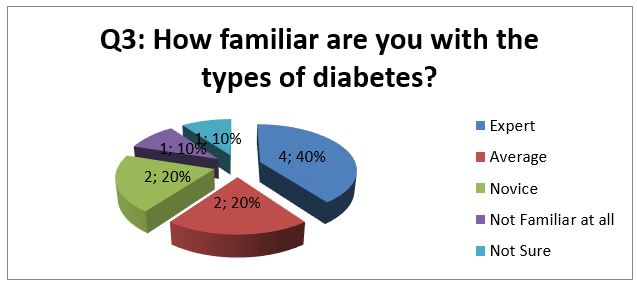

An additional 20% stated their job was to answer phones and 10% believed they were responsible for recruiting more volunteers. Since one of the primary functions of the coalition is to educate the public about diabetes, the survey also asked about the depth of knowledge coalition workers possessed, which is illustrated in Figure 3: Knowledge of Diabetes below.

Figure 3: Knowledge of Diabetes

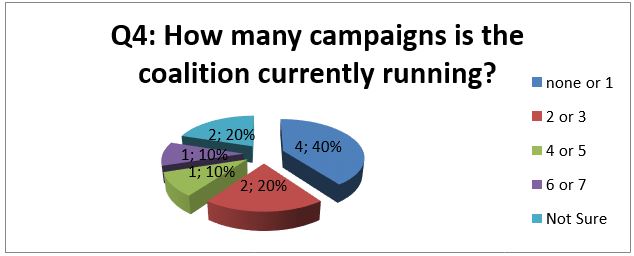

While 40% of participants indicated they had ‘Expert’ level knowledge about the types of diabetes, 10% indicated they were ‘Not familiar at all’ with the types of diabetes or ‘Not Sure’ regarding their depth of knowledge about diabetes, respectively, and 20% stated they had ‘Average’ or ‘Novice’ level knowledge, respectively. These questions summarized the query into the nature of the organization’s operations and the next three questions investigated the efficacy of the campaigns. The efficacy of the campaigns is dependent on the performance of those working on it and the results for the following question, Figure 4: Knowledge of Current Campaigns shown below, demonstrates that the workers were not sure how many campaigns were currently in operation.

Figure 4: Knowledge of Current Campaigns

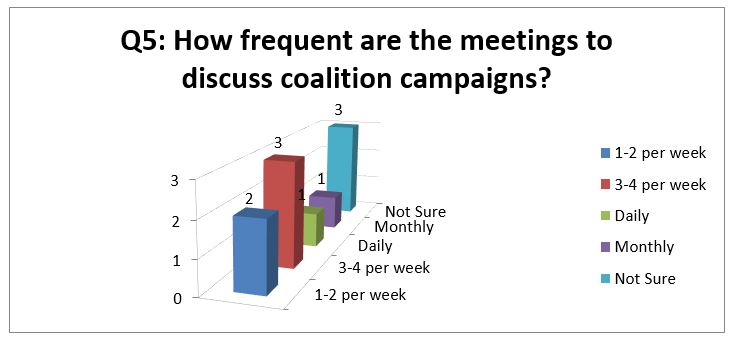

While 30% stated ‘none or 1’, 40% of those surveyed indicated that they were ‘Not Sure’ while 10% each specified ‘2 or 3’, ‘4 or 5’, and ‘6 or 7’, respectively. Additionally, the individuals surveyed were not cohesive regarding the frequency of the meetings to discuss current campaigns, which is illustrated in Figure 5: Frequency of Campaign Meetings, shown below.

Figure 5: Frequency of Campaign Meetings

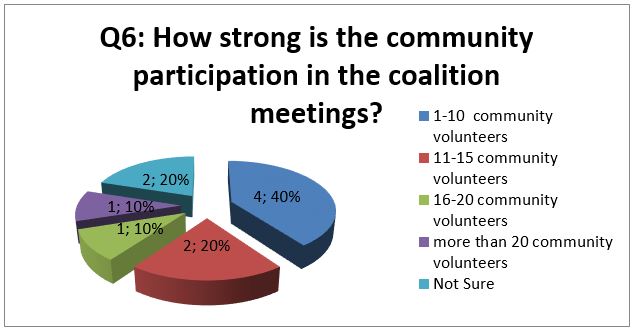

This illustration shows that 30% each thought that the meetings were three to four times per week or were ‘Nor Sure’, respectively. The ‘monthly’ and ‘daily’ options were each selected by 10% of the respondents while 20% thought the meetings were once or twice per week, respectively. Since community outreach is a large aspect of the diabetes coalition’s functionality, the participants were asked how strong the community presence was within the coalition, which is shown in Figure 6: Community Participation in Diabetes Coalition below, which illustrates that there is a lack of cohesion regarding how many community members are involved in the diabetes coalition.

Figure 6: Community Participation in Diabetes Coalition

The results show that, while 40% of the participants surveyed believe that there are as many as ten community members working with the coalition, 20% each believe that there are ‘11-15’ community volunteers or ‘Not Sure’, respectively and 10% each indicated they thought there were ‘16-20’ or ‘More than 20’ community volunteers, respectively.

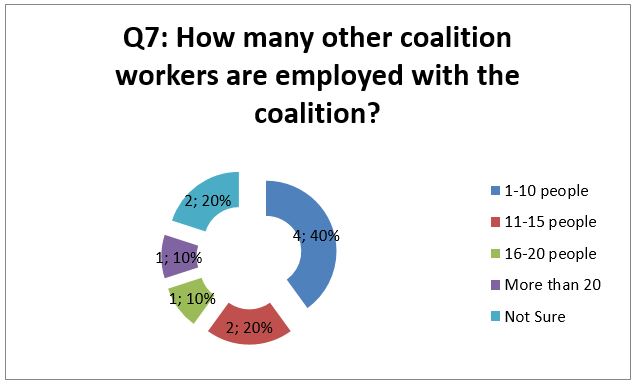

The remaining four questions were intended to assist in determining the challenges faced by the coalition in achieving their organizational objectives, which is directly relative to the number of workers and their familiarity with coalition procedures. The graph in Figure 7: Size of Diabetes Coalition Staff shown below supports the lopsided results in the previous question.

Figure 7: Size of Diabetes Coalition Staff

Once more, 40% of the surveyed participants indicated that there are as many as ten other individuals working with the coalition, 20% each believe that there are ‘11-15’ other workers or were ‘Not Sure’, respectively and 10% each indicated they thought there were ‘16-20’ or ‘More than 20’ other volunteers, respectively.

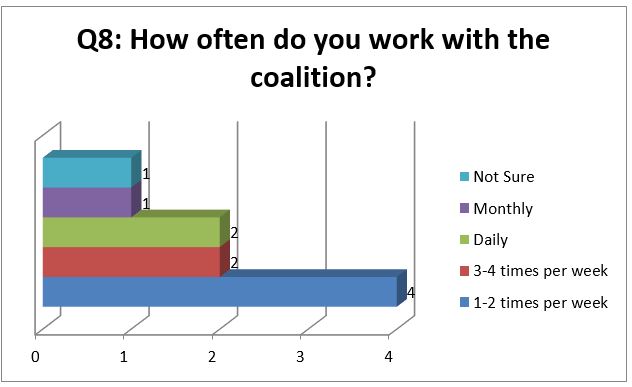

The next question asked how frequently the participants worked with the coalition, as illustrated in Figure 8: Frequency of Collaboration with the Diabetes Coalition, shown below.

Figure 8: Frequency of Collaboration with the Diabetes Coalition

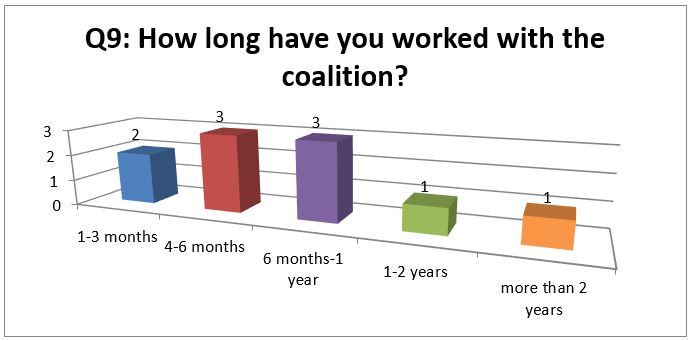

The majority of the participants, 40%, indicated that they work with the diabetes coalition at least once to twice per week, 20% stated they volunteer ‘3-4 times per week’ or ‘daily’, respectively, while 10% each indicated that they volunteered ‘monthly’ or were ‘not sure’. The short tenure of the participants with the organization is prevalent, as illustrated in Figure 9: Length of Tenure with Diabetes Coalition below, which shows that, collectively, 80% of the respondents have worked with the coalition for one year or less.

Figure 9: Length of Tenure with Diabetes Coalition

More specifically, 30% of the surveyed individuals each indicated that they had worked for the diabetes coalition for ‘406 months’ or 6 months-1 year’, respectively while 20% said they had only worked with the diabetes coalition for ‘1-3 months’. Of the remaining respondents, 10% stated they had worked with the coalition for ‘1-2 years’ or ‘more than 2 years’, respectively.

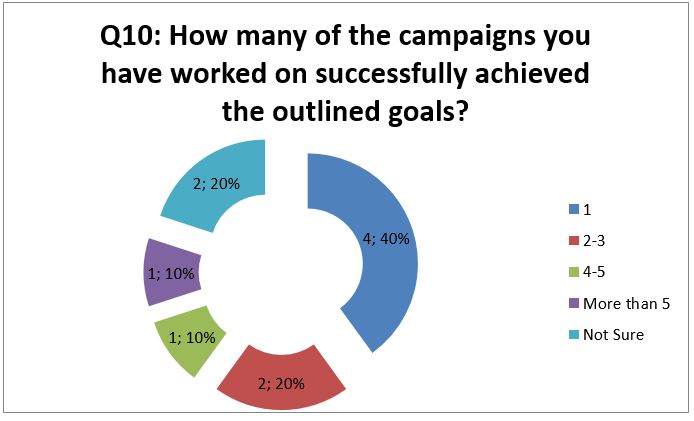

The last question is designed to garner the participants’ perception regarding the success or efficacy of the campaigns that they had volunteered to work on and the results are presented in Figure 10: Perception of Successful Campaigns shown below, which strongly correlates with the results iterated in Figure 4: Knowledge of Current Campaigns. According to the participants surveyed, the majority have worked on at least one campaign that was successful in achieving the outlined goals, with 40%stating as much.

Figure 10: Perception of Successful Campaigns

However, 20% said they had worked on ‘2-3’ successful campaigns while 20% were ‘not sure’ if they had worked on any campaigns that successfully achieved their goals and 10% indicated that they had worked on ‘4-5’ or ‘more than 5’ campaigns that achieved their goals successfully.

Discussion

The overall results of the survey revealed that the majority of the workers at the selected diabetes coalition were not professionally trained for the work they were doing since the majority of those surveyed only had a high school educational level and few had professional or technical qualifications. Additionally, there seemed to be either ambiguity regarding expected duties or unqualified individuals organizing complex events for the diabetes organization and a number of the volunteers were not properly educated regarding the types of diabetes. Since one of the primary functions of the organizations’ outreach endeavors is to educate the public about diabetes to increase awareness, this oversight can have a strong impact on the outcomes of the programs. Furthermore, there were many volunteers that had not been with the organization for very long and they did not have proper knowledge regarding the number of others working with the organization, how frequently the campaign meetings were, how many of the members were from the community, and many other relevant aspects about the functionality of the diabetes coalition. However, since many of the individuals surveyed had been with the organization for less than one year, this could have been why their organizational knowledge was so sparse.

Conclusion

There are millions of adults and children diagnosed as diabetics each year, which necessitates outreach programs geared towards helping to prevent diabetes through education. Although these beneficial programs are intended to help those with diabetes gain access to services that will help them manage their disease, there can be numerous obstacles that impede diabetic coalitions from achieving their outreach goals. Some of these obstacles can be financial, but they are also derivatives of the ability of the diabetes coalition to organize, educate, and manage the volunteers that they have. This can cause disconnects in the ability of the workers to collaborate their activities and communicate the intended goals of the current operations, which can cause campaigns to fail in meeting their outlined objectives.

Implications for Policy

This research has outlined gaps in knowledge and experience that can be the most probable explanation for the noted gaps in team collaboration that could or does impede the achievement of the program’s mission. Sources of these gaps include lack of worker knowledge concerning the other individuals they should or could collaborate with, those in the community, their specific role or duties within the coalition, and professional knowledge; ignorance regarding the different types of diabetes, the current campaigns, frequency of campaign meetings, and the specifics of the disease. Implications in this regard denote several areas policies can be improved, such as requisite knowledge of the disease before volunteers can interact with the community via telephone or otherwise to ensure quality of service.

Implications for Practice

Implications for practice present new areas that can be adjusted to improve the volunteers’ knowledge regarding frequency of the campaign meetings and how many current campaigns are active so they will be properly staffed and promoted. The volunteers should all know many operational basics and work in tandem with a tenured individual when they begin volunteering to ensure they have the proper knowledge regarding diabetes and how the coalition is organized, staffed, and when or where they are needed.

References

ADA. (2012). Diabetes basics: Type 2. Retrieved from American Diabetes Association (ADA): http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/type-2/

Aly, T. A., Ide, A., Jahromi, M. M., Barker, J. M., Fernando, M. S., Babu, S. R., . . . Eisenbarth, G. S. (2006, September 11). Extreme genetic risk for type 1A diabetes. PNAS, 103(38), 14,074-14,079. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606349103

Babbie, E. (2007). The Practice of Social Research (11th ed.). California: The Thomas Wadsworth Corporation.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

DCC. (2014). Our Mission. Retrieved from Diabetes Coalition of California (DCC): http://diabetescoalitionofcalifornia.org/

Draugalis, J., Coons, S., & Plaza, C. (2008). Best practices for survey research reports: A synopsis for authors and reviewers. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72(1), 1-6.

Nguyen, C., Varney, M. D., Harrison, L. C., & Morahan, G. (2013, February 1). Definition of High-Risk Type 1 Diabetes HLA-DR and HLA-DQ Types Using Only Three Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Diabetes , 62(6), 2135-2140. doi:10.2337/db12-1398

Vable, A. M., Drum, M. L., Tang, H., Chin, M. H., Lindau, S. T., & Huang, E. S. (2011, March). Implications of the new definition of diabetes for health disparities. Journal of the National Medical Association, 103(3), 219-223.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee