Discrimination and Prejudice in the US Criminal Justice System, Research Paper Example

Abstract

The criminal justice system of the USA has long been criticized for its racial bias and exclusion of ethnic minorities from the fair, democratic, and equal process of human rights’ protection. The violations of human rights and equality are noted at all stages of the legal system’s work, including arrests, gravity of sentencing, frequency of death penalty imposition, etc. The problems analyzed in this work include the prevalence of Black death row inmates (predominantly for murdering a white victim), and the severity and injustice of modern anti-immigration legislation (SB 1070 in particular) breaching the fundamental human rights and violating the 4th and 14th Amendments to the US Constitution. The issues of implicit and explicit bias are discussed, the history of cases on death penalty’s racially biased and capricious assignment are discussed in the paper, and possible solutions are proposed regarding promoting citizens’ education on legal procedures and non-aptness of ethnic minorities to violence. As for SB 1070, its implications for the human rights and privacy are discussed, the explicit violation of federal legislation and the US Constitution are laid out, and the consequences of such laws’ adoption are provided. The conclusion reached in this paper relates to a lack of information on ethnic minorities causing fear, misunderstanding, and moral panics. Thus, recommendations for action include education and closing the gap between nationalities on the way to mutual comprehension, tolerance, and inclusion.

Globalization and improvement of means of communication and transportation have contributed to the gradual erasure of geographical boundaries, and the emergence of the concept of a “global village”. Today, people connected to the Internet may communicate with their friends in any distant corner of the world; those having enough funds or traveling on business may visit many different countries and get familiarized with exotic cultures and people. The global labor force is constantly migrating from country to country mainly due to the emergence of a global labor market. Thanks to the globalization forces, populations are becoming more diverse and multicultural, and people are facing the higher need for accepting and integrating people they used to label as “others” in their immediate social surroundings.

The USA has historically been one of the most diverse countries in the world, and it has always attracted people from other countries with its high standards of living, beneficial employment opportunities, and other attractions for immigrants. Therefore, at present, Americans are in constant interaction and communication with immigrants, tourists, expatriates, refugees, visiting students, business people, and other categories of foreigners coming to live in the USA for a certain period of time (The Criminology and Criminal Justice Collective of Northern Arizona University, 2009). Under such conditions, it is becoming exceptionally important to nurture the culture of tolerance and acceptance among the US population to maintain harmonious and friendly social climate in the country.

Despite the fact that the USA is considered one of the most advanced democracies in the world, the melting pot welcoming people from virtually every corner of the modern globe, the issue of race and ethnicity persists as an acute social problem. Coal, Smith, and DeJong (2012) emphasized the fact that the US criminal justice system is racist, as at present, researchers and practitioners repeatedly note a variety of biased attitudes among criminal justice workers towards racial and ethnic minorities. The present situation is highly alarming because the violation of racial equality is a direct breach of the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution securing respect to people of all nationalities, races, and skin colors in this country.

A case of racial bias in the criminal justice system may be detected in case people arrested and tried for a similar offense receive different sentences. According to the statistical report of the Sentencing Project, in 1995, 32.2% of all African American males in their twenties were in jail or on probation; in 2000, as Free (2003) reported, 188,500 more African American males were in prison than those enrolled in higher education. However, these statistical data do not imply that African Americans are more violent, anti-social, or criminally inclined people; such evidence indicates excessive attention from the side of police officers towards representatives of ethnic minorities. One of such examples may be taken from the 2005 report of the Houston Police Department about 12% of African American drivers, 9% of Hispanic drivers, and only 3.7% of white drivers stopped and searched in the streets (Cole et al., 2012). Moreover, research has shown that black drivers faced the 47% higher likelihood of receiving a citation than white drivers had, while those chances for Hispanic drivers were 82% higher (Cole et al., 2012).

Some later unsatisfying statistics was provided by Walker et al. (2012): in 2009, there were 6.7 times more African American males in the state and federal prisons as compared to the white inmate population. In 2010, Arizonian courts considered several cases of unreasonable racial profiling in terms of stopping and checking the immigration status of people based only on their appearance features. It is also notable that Native American women are raped and sexually assaulted much more often than African American and white women are (Walker et al., 2012). Muslims also face pressure and racial discrimination issues in the USA, especially after the 9/11 events – 19% of American Muslims reported being exposed to a certain form of discrimination in 2007, which implies that race still matters in the USA.

In general terms, the US crime rates have decreased by 22% between 1991 and 2000, which indicates the rise of the socio-economic standards of life (Free, 2003). Nevertheless, the problem of overrepresentation of the population of color in detention institutions remains a fact, both for mature and juvenile delinquents. Cole et al. (2012) also added that racism in the US criminal justice system is manifested in stereotyping of offenders and evidence. The authors cited evidence of Asian American defendants’ receiving less severe sentences than those of African Americans and Hispanics. Moreover, as the case with the Harvard Professor Gates’ arrest showed, racist attitudes persist in every step of the criminal justice system, such as arrest, detention, sentencing, death penalty, juvenile delinquency, etc. (Cole et al., 2012).

However, one of the most striking injustices and imbalances in the American criminal justice system is that of the racial bias in death penalty. As Love (2012) admitted, the application of the US death penalty sentence is unfair and arbitrary, often based on the race of the defendant. Moreover, the outcome of the legal case for the defendant often depends on the county in which the case is prosecuted. The author illustrated such an opinion with the Senate Bill 9 approved by the North Carolina Senate that repeals the state’s Racial Justice Act adopted in 2009 and allowing inmates to file appeals with reference to racial discrimination’s statistics. The bill was vetoed, which saved the US courts from officially confessing to racially biased decisions. However, it is still a fact that in North Carolina, black criminals whose victims are white are 3.5 times more likely to be sentenced to death (Love, 2012).

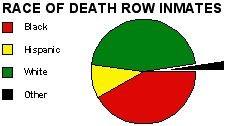

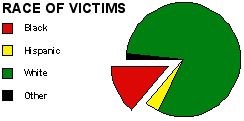

Racial bias in the US decisions on death penalty has a long history of existence – at present, there are more than 41% of Black defendants awaiting their death penalty in the death row, as Figure 1 suggests. The number of white defendants is even slightly higher (44.74%), which may imply that there is no racial disparity in assigning death penalty to defendants. However, the race of victims (Figure 2) shows that more people are sentenced to death for killing white victims (78.67%), while the death of black victims is punished by a death penalty only in 14.2% of cases.

Figure 1

Source: from Death Row Population Figures from NAACP-LDF “Death Row USA (January 1, 2009)”

Figure 2 Race of the Death Row Inmates’ Victims

Source: from Death Penalty Information Center (2009)

Such statistics implies that there is still a difference in terms of death penalty imposition, and one should also keep in mind that Figures 1 and 2 reveal the nationwide statistical data, while rates of death penalty cases differ substantially from state to state, with the racial opposition intensifying in southern states. According to the Top Tens (2013) rating (a national open resource representing votes of Internet users), Mississippi is the most racist US state, while Alabama occupies the second place in the rating, and Texas is the third, and Georgia is the fourth most racist state. The authors of the Equal Justice Initiative (2013) indicated that in Alabama, the annual rates of murders involve 65% of black victims, but 80% of people convicted to death are accused for killing white people. Moreover, death row inmates accused for killing black victims constitute only 6% of the whole death row inmate population in Alabama, and over 60% of all Black inmate population in the state has been accused for killing a white person.

Alongside with Alabama that has already been discussed, Texas has recently witnessed the first execution of a white person for killing a black person – before that, no white criminal was sentenced to death penalty for killing a representative of an ethnic minority (Recinella, 2004). Georgia is also known for outdated, 19th-century-like practices in terms of death penalty, being the primary US executioner, and executing 337 black people as compared to only 75 white people from1924 to 1972 (Recinella, 2004). Even in Washington, death penalty decisions are seen to be heavily affected by racial factors, as death notices have never been filed for the cases in which a white defendant would kill a black victim, and 42% of death notices were filed for black defendants killing white victims. 90% of all death row cases of 2004 involved a white victim, and none of them involved a black victim. Moreover, all jurors who convicted black victims to death sentence were white, which indicates that very few African American jurors were allowed to hear death sentence cases of black defendants (Recinella, 2004).

As one can see, there is a clearly delineated racial geography of death penalty in the USA, which may be partly explained by the long history of slavery and nationalism that the modern strive to multiculturalism and inclusion cannot combat. However, the comprehension of racial disparities in the death penalty is also impossible without knowing the history of anti-racist struggle in terms of death penalty legislation. The earliest case in which the defendant managed to dispute the death penalty based on the racially biased sentencing process and outcome was the Furman v. Georgia (1972) case. During the review of that case, Justices officially acknowledged the existence of racial bias in the country’s administration of death penalty, and the following case, Gregg v. Georgia (1976), moved the issue even further. The Court refused the fact that historic racial bias could not be eliminated, thus invalidating the constitutionality of capital punishment (Bedau & Cassell, 2005). The US legal system’s history also has well-documented scandalous and audacious cases (like the McCleskey v. Kemp (1987) case) in which the court officially acknowledged the inevitable existence of race-based disparities and their ever-present effect in the decisions about death penalty. The controversy persisted and required action, and corresponding decisions were made, though one can hardly consider them adequate and constitutional:

“expressing the concern that responding to racial bias in death penalty might necessarily require confronting racial bias in other criminal cases, the Court concluded that the Constitution does not place such “totally unrealistic conditions” on the use of capital punishments or the administration of criminal justice” (Bedau & Cassell, 2005, p. 86).

This decision made in the McCleskey v. Kemp (1987) case gave rise to the strong opposition to officially acknowledged tolerance to the presence of racial bias in the legal system, and its acknowledgement as a decisive factor in decisions about death penalty in one of the most advanced democracies of the world. As del Carmen, Vollum, Cheeseman, Krantzen, and Miguel (2010) explained that, the court did not dismiss the validity of statistical evidence collected by McCleskey on the subject of racial bias in making death penalty decisions, but it considered it insufficient for the case review, which led to McCleskey’s execution.

Butler (2008) also recognized the problem of racial bias in death sentencing, and stated that such a bias is conventionally correlated with the district attorney’s ethnic background, with the racial breakdown of the jury in capital cases, with the misunderstanding of instructions by the jury, and with the jurors’ attitudes to death penalty and their death qualification status. Moreover, the physical appearance of Black defendants may be associated with overt racial stereotypes, which may contribute to an excessively strict and negative attitude of the jurors to the defendant, resulting in a severer sentence. There are certain attempts to limit the potential impact of these aggravating factors, but as Recinella (2004) indicated, the Racial Justice Act, a model law aimed at providing ethnic minorities with the right to legally challenge a racially motivated death sentence, has been so far endorsed only in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, while no other state displays eagerness to follow its example. Moreover, the refusal of legislative agencies to enact any sort of legislation to manage racial disparities in the American death penalty system is a recognize fact, and even the mounting statistical evidence for the presence of such a bias does not contribute to the search for the solution to the problem.

Lynch and Haney (2000) conducted an extensive study addressing two major research gaps in the field of criminal justice nowadays: lack of comprehension of capital penalty-phase jury instructions, and discriminatory death sentencing. Their quasi-experimental study showed that Black defendants were treated slightly more punitively, and the discriminatory effects of legal treatment were concentrated among participants with the poorest comprehension. The authors’ findings suggested, “racially biased and capricious death sentencing may be in part caused or exacerbated by the inability to comprehend penalty phase instructions” (Lynch & Haney, 2000, p. 337).

In line with recognizing the explicitly striking controversies about death penalty imposition influenced by racial considerations, researchers repeatedly note a much more dangerous tendency – an illicit racial bias persisting even in people considering themselves racially tolerant and color-blind. As Levinson and Smith (2012) explained that,

“Although we are increasingly unlikely to admit to harboring (or even to be consciously aware of) negative racial attitudes, a plethora of research studies show that people of all races continue to harbor negative implicit biases against black citizens and members of a variety of other groups. Indeed, implicit social cognition studies often detect bias in people who sincerely believe that they are color-blind or race neutral” (p. 231).

These findings have to be kept in mind when the decision-making process at the death sentence case is considered. The authors emphasized that a decision to sentence someone to death is always inherently subjective, and it most often depends on the mechanisms of quantifying harm – it is true that all murders constitute a horrible crime, but some specific factors make the jury decide that specifically that crime is the worst representation of evil in the human being, and that criminal has to be deprived of life. Capital sentencing determinations are driven by the interplay of emotional and moral processing mechanisms, which takes place differently with various perceptions regarding the defendant. Consequently, in case the black skin color is unconsciously associated with elevated dangerousness in the jurors’ minds, they are more likely to make a decision in favor of death sentence than they would have done in case they were reviewing the case of a white defendant causing fewer subconscious concerns and fears (Levinson & Smith, 2012).

Fortunately, there is a positive change in some states regarding the official acknowledgement of racial bias as playing a role in the imposition of death penalty. For instance, as the Death Penalty Information Center (2012) experts reported, on December 13, 2012, Superior Court Judge Greg Weeks changed death penalty sentences to life sentence without parole for three death row inmates after finding out that race played a significant role in the jury selection for the cases. The present decision was made on the basis of North Carolina’s revised Racial Justice Act.

The second problem deserving special attention in the USA is racial profiling, that is, expression of a certain racial bias based on only the physical characteristics of the population. Some examples of racial profiling include stopping and searching people in the streets, stopping drivers on the roads, etc. based on their ethnic minority appearance. Most often, as the experts of The Criminology and Criminal Justice Collective of Northern Arizona University (2009) indicated, racial profiling stems from the illegal immigration issues, and takes the form of “moral panics” defined as “exaggerated social reactions to perceived deviance from and threats to societal values”. Unfortunately, it has been proven that powerful official and public agencies take an active part in the creation and maintenance of moral panics among the population; these include the press and broadcasting agencies, politicians, governmental agencies, pressure groups, claim seekers, police, law enforcement agencies, and public opinion groups (The Criminology and Criminal Justice Collective of Northern Arizona University, 2009). One of such “moral panics” manifestations in 2010 has become the adoption of the Arizona Senate Bill 1070 – the anti-immigration law characterized as the harshest piece of anti-immigration legislation ever adopted in the USA (Spencer, 2012).

Though according to the Top Tens (2013) rating, Arizona is on the tenth place regarding racist attitudes, one should note that Arizona is the state involved in a great scandal regarding racial discrimination and injustice in the state legal and criminal justice system. The Senate Bill 1070 (SB 1070) has become the issue of great controversy among American and Arizonian lawmakers, politicians, judges, and law enforcement officials, since it was officially deemed as racist and violating the US Constitution. It initially emerged upon the initiative of Senator Russell Pearce as an effort to struggle against the rising numbers of Arizonian border crossings undertaken by illegal Mexican immigrants.

After a series of accusations directed at federal law enforcement forces for the inability to control the illegal aliens’ influx to the state of Arizona, Senator Pearce proposed the SB 1070, which was signed by Arizona Governor Jan Brewer in April 2010. Nevertheless, it took less than three months for SB 1070 to exist as a law, and its constitutionality was soon disputed by the Supreme Court that invalidated SB 1070 on the basis of the preemption rule – no state legislative agency can assign state law enforcement forces with the responsibility traditionally held by federal law enforcement agencies, which is the issue about control over illegal immigration (Kubrin, Zatz, & Martinez, 2012). The most scandalous provisions of SB 1070 challenged by the Supreme Court were however not only the assignment of federal duties to state agencies, but the racial profiling and discrimination provisions such as section 2(b) and 6 of the bill.

Section 2(b) gave the legal right to police officers to stop and search individuals in the streets, and ask them to show documents proving their immigration status. The only precondition allowing police officers to ask for such documents was the probable cause – a reasonable suspicion of the individual’s illegal alien status. However, there were no factors against which the reasonability of suspicion would be evaluated included in SB 1070 provisions. Section 6 put all people with an appearance different from white Caucasian standards into an even greater threat – Arizonian police officers were allowed to arrest people without a warrant in case they were unable to provide their immigration documents. Such a provision breached all principles of constitutionality, privacy, and protection of human rights and dignity, and put all people under threat of being arrested when jogging or leaving a home for the nearby supermarket to buy food (Garcia, Eig, & Kim, 2010).

Overall, Magana and Lee (2013) characterized SB 1070 as the most unfair piece of anti-immigration legislation within the whole history of the USA, mainly because it aggravated the punishment not only for illegal aliens once they were caught without immigration documents, but to their potential employers or people renting apartments to them. Thus, the one-time detection of employers knowingly hiring illegal aliens was $1,000, and subsequent detections presupposed harsher fines and even the possibility of imprisonment. Applied in real-life settings, SB 1070 did not bring about a positive change in the volumes of Mexican immigrants flowing to the Arizonian cities; instead, it gave an official opportunity for law enforcement officers to reveal their racial biases and conduct racial profiling of people they encountered in the streets. Spencer (2012) reported numerous cases of racial bias manifested in police officers’ behavior during the time when SB 1070 was still in force, as they had an official right to harass people with Hispanic appearance, asking them for documents and proofs of their legal immigrant status in the public places, in the streets, during car stops, etc.

It is notable that the US legal system has been witnessing a series of efforts on restructuring the decision-making process through which decisions about sentencing criminals to death are made. The most immediate solution to making death penalty more justifiable and reasonable was to shorten the list of first degree murders from which death penalty can be imposed. Moreover, the jury was obliged to preliminarily determine the special distinguishing factors because of which the decision about death penalty was made (Lynch & Haney, 2000). Moreover, the “guided discretion” reform was undertaken to ensure that capital sentencing jury follows the strict set of sentencing instructions. However, there is still little evidence on the ways in which these reforms have been implemented, and the extent to which they have contributed to making death penalty sentences more objective and unbiased.

Consequently, one of the most viable solutions to the problem of racial bias in death sentencing may be given in terms of conducting more empirical research for collecting evidence on the feasibility of death penalty-related reforms. In case reforms are successful, they may be further pursued by the policymakers, while in case they are ineffective, measures have to be taken to ensure adaptation or readjustment of those reforms to make them more effective. It is a highly necessary step in the present-day legal system because any reform requires significant funding, and in case it does not work, there is no sense in spending considerable amounts of taxpayer dollars for insufficient programs and policies.

As evidence analyzed in the present work suggests, the problem of racism in the US criminal justice system is grave, and there is little understanding and consensus even among the key US policymakers regarding possible solutions to the issue. As Cole et al. (2012) suggested, there is a need to consider the role of citizen education as one of the possible solutions to racial bias in criminal justice. According to these researchers, “individuals can try to be educated about issues of race and be self-conscious about their own attitudes and behavior” (Cole et al., 2012, p. 126). Implicit racial bias is even more dangerous than explicitly shown racial hatred is, as it may be concealed under the mask of tolerance and acceptance, and may find its manifestations in unexpected, unprecedented socio-political, legal, and ethical situations.

Nevertheless, such a change may be only one of the aspects of a complex approach to revolutionizing the criminal justice system in legal terms – criminal justice officials are people, but they still use a set of legal procedures and laws to administer justice, which has to be changed as well to tackle the problem of racism in the criminal justice system. Laws similar to SB 1070 have to be banned and blocked at the initial stages of their emergence, and legislation providing “windows” for racial profiling, racial bias, and racial discrimination has to be detected and eliminated from the US criminal justice system to provide feasible racial justice and equality conditions and the creation of a more tolerant, harmoniously existing multicultural society. Though the problem of illegal immigration is still severe in the USA, and the federal forces’ inability to manage it effectively aggravates inter-racial tensions, there is need to provide citizens with more accurate data on the feasible damage from illegal immigration, which is not as high as moral panics’ stimulators try to display it. This way, the US society may put aside the tensions rising from lack of knowledge about ethnic minorities and their lives, their aptness to crime and violence, etc., and move towards a new lifestyle based on tolerance, acceptance, mutual understanding, and inclusion.

References

Bedau, H. A. & Cassell, P. G. (2005). Debating the Death Penalty: Should America Have Capital Punishment? The Experts on Both Sides Make Their Case. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Butler, B. (2008). Racial bias and the death penalty. In Butler, B. L. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Psychology and Law (pp. 671-673). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Cole, G. F., Smith, C. E. & DeJong, C. (2012). The American System of Criminal Justice. (13th ed.). Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

Death Row Population Figures from NAACP-LDF “Death Row USA (2009). Retrieved from http://www.deathpenalty.org/article.php?id=54

Del Carmen, R. V., Vollum, S., Cheeseman, K., Frantzen, D. & Miguel, C. S. (2010). The Death Penalty: Constitutional Issues, Commentaries, and Case Briefs. (2nd ed.). Newark, NJ: Elsevier.

Equal Justice Initiative (2013). Racial Bias. Retrieved from http://www.eji.org/deathpenalty/racialbias

Free, M. D. (2003). Racial Issues in Criminal Justice: The Case of African Americans. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Garcia, M. J., Eig, L. M. & Kim, Y. (2010). State Efforts to deter Unauthorized Aliens: Legal Analysis of Arizona’s SB 1070. Washington, DC: DIANE Publishing.

Kubrin, C. E., Zatz, M. S. & Martinez, R. (2012). Punishing Immigrants: Policy, Politics, and Injustice. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Levinson, J. D. & Smith, R. J. (2012). Implicit Racial Bias Across the Law. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Love, D. A. (2012). The racial bias of the US death penalty. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/cifamerica/2012/jan/03/racial-bias-us-death-penalty

Lynch, M. & Haney, C. (2000). Discrimination and instructional comprehension: Guided discretion, racial bias, and the death penalty. Law and Human Behavior, 24(3), pp. 337-358.

Magana, L. & Lee, E. (20133). Latino Politics and Arizona’s Immigration Law SB 1070. New York, NY: Springer.

Most Racist States in the U. S. (2013). The Top Tens. Retrieved from http://www.thetoptens.com/most-racists-states-us/

Race and the Death Penalty (2009). The Death Penalty Information Center. Retrieved from http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/race-and-death-penalty

RACE: Three More Death Sentences Reduced in North Carolina Because of Bias in Jury Selection (2012). Death Penalty Information Center. Retrieved from http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/race-three-more-death-sentences-reduced-north-carolina-because-bias-jury-selection

Recinella, D. S. (2004). The Biblical Truth about America’s Death Penalty. Richmond, VA: UPNE.

Spencer, M. (2012). A Moment in Time: Issues that Enhance Spiritual Multiplication. Bloomington, IL: WestBow Press.

The Criminology and Criminal Justice Collective of Northern Arizona University. (2009). Investigating Difference: Human and Cultural Relations in Criminal Justice. (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Walker, S., Spohn, C. & Delone, M. (2012). The Color of Justice: Race, Ethnicity, and Crime in America. (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee