Diverse Potentiality, Research Paper Example

Today’s student body combines online and on-campus courses, juggles work and perhaps even a family with their academic and social lives, and specialization and technological advances allow motivated adults to study the same material for use in a variety of career paths. Paradoxically, the on-campus presence is in just as much danger of becoming a transient presence in an educational program. For this and many other reasons, FlexNet courses, such as the one proposed herein, operate almost entirely online. While this delivery method offers many benefits, it challenges the instructional designer to incorporate an expectation of this diversity into the curriculum in a way which enriches it- rather than detracting from it. Hence the student’s mastery of the concepts of privacy and HIPAA depend overcoming differences of cultural, linguistic, and experiential differences in students.

Commonality in Assessment

Traditional assessment typically involves written materials which either require the students to choose the best response in one form or another or task students with writing fill-in-the-blank, short answer, essay, or other open-ended responses to written items (Jenkins, 2010). These approaches are very demanding for students whose speak more than one language or who do not speak English fluently; three of the five students fulfill these criterion for the reconsideration of traditional assessment. However, Hay, Tan, and Whaites (2010) write that traditional assessment devalues the potential of emerging approaches to differentiated instruction. An example of a typical traditional curriculum might be the present-test-demonstrate-supervise cycle which instructors depended upon for teaching, assessing, and ensuring the proper application of the material. For medical students, simply being lectured on every aspect of HIPAA is unreasonable, and the realistic ramifications of this knowledge in the modern world of health care may leave the livelihood of each student’s career aspirations- and the subsequent millions of dollars in penalties or suits- to students who may have difficulties of time management, personal management, linguistic fluency, inexperience, etc.

The quantitative measures of graduate outcomes provided in “Assessing Higher Education’s Learning Outcomes” (AHELO) compares post-secondary education across the world, focusing on the feasibility of student general skills, subject-specific skills, skills added through contact with tertiary educational programs- divided into raw scores of individual students and incremental or ‘value-added’ learning- and contextual learning based upon broader appropriate outcomes of career competency (Hattie, 2009). Building a learning community is one of the essential components of a successful classroom- whether on-campus or online- and modern education often integrates technology with the curriculum to maximize the effects of a lesson. Fujuan et al. write: “Advancing technology in distance learning has allowed education to transcend the boundaries of brick and mortar schools and classrooms” (2010, p. 10).

Difference in Assessment

From the gathered information regarding the students’ experience levels, it can be deduced that these students either participated in health-related programs early in life or are representative of the larger, diverse numbers of entering students coming from the older generations. Hay, Tan, and Whaite (2010) write that the number of students who are expected to enroll in higher education programs during the next seven years should fall among students within three years of their secondary graduation but is likely to increase among older groups (p. 578). This presents more instructional challenges; making references and citing examples which are relatable for the majority of the students, providing applied workplace knowledge without neglecting important theoretical foundations and rhetoric, and adjusting to the technological capabilities of the class are but a few of the complications of an age-diversified classroom. Fujuan et al. (2010) also demonstrate that students from Eastern cultures experience a culture shock which includes their experiences with higher education. Specifically, the authors write that Eastern cultures tend to embrace more collaborative and less-independent functions of the person as a whole within the society. Higher education in general, and especially in the specific sub-set of current and future workers in the health care community, encourages a greater level of autonomy and a wider range of skills then Eastern students may be accustomed to. While instructors must uphold this expectation to ensure viability in Western careers, the transition is eased by a multicultural system of overriding class ethics of common decency and interdependency during preparation and study. International students may avoid taking more than one class at a time due to the immense linguistic and sociocultural burdens of adjusting to both a new way of thinking about a career field and about society’s relationship with health care and health care workers. While the briefly-examined assessment methods have in common a flexibility of conceptualization appropriate for the online format, each displays varying levels of reliance upon the skill sets of the instructor and student as well as being limited by the context of use. According to Hattie (2009), clarity, the use of reciprocal instruction, and feedback are the eighth, ninth, and tenth most effectual components of higher education. All of these assessment methods are indeed useful when carefully implemented, monitored, and adapted within the situational scope of student culture and mastery. Jenkins (2010) writes about assessment results as a form of direct, objective feedback which informs student decisions and self-measurement of progress. The engaged student then informally develops an inventory of their knowledge and determines the validity of the instruction received, their score in relation to the instruction, and the gaps in their knowledge and ability to practically apply information.

Assessment Selection According to Class Population

Jenkins (2010) warns instructors that “As well intentioned as formative assessment is, the effectiveness of it is reduced if students are not appropriately informed of what they are expected to demonstrate a knowledge of (p.567). In other words, students must do more than repeat facts and demonstrate a concept once, they must apply it well. As stated in the introduction, student mastery differs greatly in regards to cultural background, linguistic fluency in English, and the level and type of experience in an area of the health care field. Although adjustments for student learning styles generally exhibits a positivity of attitude, Tublure (2010) warns that critics of differentiated instruction believe that overexposure to one type of learning may cause the student to become complaisant or inured to their individualized learning environment (p. 82). After reviewing the capabilities of these five students and the literature of various assessments, an alternating concept mapping-multiple choice- audio-visual formative assessment was selected as a primary method. Concept mapping considers the limited linguistic skills of some students and allows for creative expansion while also keeping in mind that students whose learning depends upon organization can benefit from developing broader schemas for learning. Concept mapping can be completed in a variety of formats: artistic renderings, software models, audio-visual lectures, etc. Engaging pre-existing student interests and skills should increase comprehension and retention. Providing specific guidelines and examples will be crucial to the outcome of this assessment. Multiple choice questions should include the exact terminology utilized during study but should not exclude alternate analogous terms, i.e. ‘privacy’ versus ‘protection of personal rights and information’. If students are not aware that those two terms are analogous, then the curricular unit cannot reach the necessary outcomes. Finally, audio-visual assessments may form a range of manifestations. Online students, especially, are well-acquainted with the basic information technologies, such as Microsoft Office programs and PowerPoint. Appropriate usage of webcams, YouTube, microphones, and other audio-visual equipment are also encouraged but not necessarily required. The students may opt to come in for an interview or to select musical accompaniment.

Although an alternating concept mapping-multiple choice- audio-visual formative assessment has been selected as the primary assessment method for this FlexNet course, the principles of Chickering’s 1969 and 1993 qualitative models of education molded the conceptualization of how this alternating formative assessment should be engineered for the greatest benefit (cited by Hattie, 2009). The Chickering models focus on the following seven areas: competency, coping with emotions, collaborative benefit, the establishment of independence, the establishment of identity, the development of purpose, and the development of integrity (Hattie, 2009). By varying the foci of assessment at regular anticipatory and reflective intervals throughout the semester, six of the seven areas formed the heart of the strategy utilized. (Emotional coping requires more time and possible infringement upon the very sort of safety and security laws which this HIPAA unit emphasizes.)

Discussion

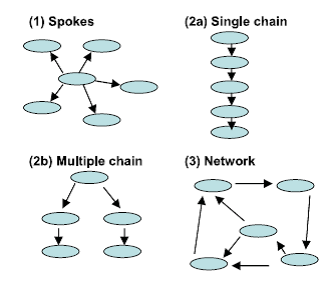

The alternating concept mapping-multiple choice- audio-visual formative assessment (MCAV) should occur at regular intervals with indications given to students about the expectations of information. Both formal and informal assessments should be accompanied by clear directions, guidance, and examples all written in simple language (Jenkins, 2010). For concept mapping with regards to HIPAA, the student could utilize a pre-formed map divided into the categories of administration, security rules, privacy rules, standards, and effects. If the student opts to use the pre-formed map, then a couple of simple terms or definitions should be provided, such as ‘sanction’ or ‘risk management’. (See Appendix 1 for a snapshot of an adaptable continuing education summarization for inclusion in instruction and assessment formation.) Duties, such as paper shredding, quotes regarding standards, and points of contention, such as the classification of psychotherapy notes, should be included as well and in simple language. The various types of simple concept maps are illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Types of Simple Concept Maps (Hay, Tan, & Whaites, 2010, p. 582)

The pre-formed concept map provided for the assessment may utilize the multiple chain or the network formats, depending upon the specific objectives for which the assessment is designed. If time allows, the terms and definitions be provided in simple German- prior to assessment- by using the translate feature in Microsoft Word. Although it will not be grammatically-correct, it should aid Olga’s comprehension of the material and minimalize confusion by providing two translations against which she can evaluate her learning. The English version, as used in assessment by the entire class, takes precedence over other languages unless a documented linguistic disability requires reasonable accommodation.

Multiple choice answers reduce the likelihood of overcomplicating a test. Commonly used to assess detail recall, multiple choice answers make objective scoring a simple matter of matching letter answers to a columned key (Hay, Tan, & Whaites, 2010). Although they are derided as a traditionalist’s easiest method, multiple choice answers may be configured to initiate critical thinking. When two answers are correct and one is simply more appropriate, the student may assume that only one is correct, discover their error only after grading, and perhaps be reminded of the importance of avoiding the carelessness which HIPAA seeks to eliminate. When students do read each answer and find the two correct ones, they may rationalize, compare and contrast, deduce, or use any number of critical thinking and test-taking skills to reach their conclusion about which answer is best. Standardized answer keys complicate formative assessment procedures and often prove to be time-consuming and prone to student errors of visual mismatch. Additionally, skilled test-takers experience the advantages of being familiar with their design (p. 581).

The final element in the primary cycle of the selected formative assessment, audio-visual integration, enhances retention, comprehension, and student responsiveness to questioning- provided that it is skillfully managed in conjunction with the lesson itself. Audio-visual assessments should not be formulated without an association to a larger factual or symbolic meaning. One particular example would be the use of Microsoft PowerPoint. Some students choose to use multiple animations on each slide, detracting from the effectiveness of their presentation as a whole; other students insert animations, designs, sound effects, and other audio-visual cues which are disconnected from the content. Multi-colored bubbles do not enhance a student’s presentation about HIPAA’s stringent guidelines for the protection of both health care worker and patient—unless the student makes a reference to relevant myths and ‘popping your bubble’. In short, audio-visual elements are subjected to student discretion in a largely-independent degree which can empower or overwhelm the student. Fujuan et al. (2010) generally praise the impact which technology has upon the integration of international students learning English and participating in classes but still gently reminds instructors that these students must adjust to “learning situations compounded by lack of knowledge, understanding of the values and language of the teaching culture, and strong values, attitudes and perceptions of their own” (p. 10). Providing a simple resource to keep the assessment focused, such as the continuing education summarization of HIPAA provided by Hixson and Hunt-Unruh, may focus their efforts on a specific area (2008). Students should be encouraged to conduct informal peer reviews which follow the same rules of courtesy observed by the online class in general. Creating opportunities for interaction is assumed to be a part of the curriculum, negating the need for peer involvement in this particular assessment process. Still, feedback from varying viewpoints lends credibility when an agreement is reached; instructor intervention may also be required.

For alternative assessment, rubrics provide a flexible but also highly-subjective format for awarding weighted points to specific goals for assignment completion. Nonetheless, the flexibility of rubrics allow the instructor to isolate certain objectives in such a diverse classroom (Reddy & Andrade, 2010). Rubrics for one assignment may focus primarily on the mastery of concrete elements of the unit, such as detail recall and the ability to apply information to a given problem, while rubrics for another assignment may award points for improvement, effort, critical thinking, originality, etc. For example, the students may debate the status of Personal Health Records (PHRs) under HIPAA and argue that PHRs should be either included or excluded from the general requirements of the previous health care laws. After the students have all selected a perspective, introduce relevant reading material, such as Rakestraw’s 2009 journal article “ONE SIZE DOESN’T FIT ALL: WHY HIPAA SHOULD NOT BE EXTENDED TO COVER PHRs”. The students consider this article and compose a response. The rubric evaluates the entire process of learning and how it is deepened- regardless of each student’s position on the issue. This encourages the students to expand on both fronts: building and interpreting information and comparing perspectives to reach a more complete knowledge of health care in general. Students themselves reported that rubric use was effective in “reducing uncertainty and doing more meaningful work… evaluating their own performances…especially on weaknesses…and focusing their efforts so as to improve performance on subsequent assignments” (Reddy & Andrade, 2010, p. 438). It should be noted that rubrics can be utilized as an alternative assessment or provided as a form of feedback for the students.

Conclusion

Hattie (2009) shatters the illusions of higher education by proposing that 1) self-reporting indicates a student desire to achieve only that which is comfortable to reach, 2) the assessment of the student empowers less positive change than assessment of the teacher by the student, 3) students are more likely to achieve difficult goals—or at least achieve greater than they expect to achieve, 4) learning must be spaced to allow for reflection and to avoid overwhelming the student, and 5) the quality of teaching is not as vital to learning as the transparency of instructor expectations. Any one of these findings uproots centuries of abstract educational pedagogy, emphasizing the central point of the curricular adaptations proposed herein: no assumptions regarding the student body are valid. This alternating concept mapping-multiple choice- audio-visual formative assessment regards each of the three central components as representative of a different set of skills, propensities, and learning styles.

Tulbure (2011) remarks that the research regarding such modifications is still limited and mixed with regards to possible best practices and that the majority of professors continue to deliver instruction in the same manner regardless of the different challenges and potentialities which the students of each new class pose. Because of such uncertainty, instructors should realize that the potential improvement afforded by conscientious differentiated instruction has yet to be seen and may be great enough to prevent students from skimming over the important elements of HIPAA due to the dry, lengthy, and detailed nature of its many specifications and due to the common lack of its application to dilemmas commonly occurring in the workplace. Critical thinking must not be disengaged from this unit, and the alternating formative assessment cycle includes both traditional and non-traditional elements which embrace each learning style and the individual’s differences of background. This challenge is likely to increase as more students in their thirties (or more advanced years) enter higher education, but Jenkins (2010) lauds formative assessment for increasing the dialogue which will affect change. Still, this change must be implemented by instructors and examined for usefulness, and even new approaches can and should be guided by appropriate existing standards (Hixson & Hunt-Unruh, 2008). Like so many aspects of education, the best choices and the hard decisions fall to the instructor.

References

Fujuan, T., Nabb, L., Aagard, S., & Kioh, K. (2010). International ESL Graduate Student Perceptions of Online Learning in the Context of Second Language Acquisition and Culturally Responsive Facilitation. Adult Learning, 21(1/2), 9-14.

Hattie, J. (2009). The Black Box of Tertiary Assessment: An Impending Revolution. In L. H. Meyer, S. Davidson, H. Anderson, R. Fletcher, P.M. Johnston, & M. Rees (Eds.), Tertiary Assessment & Higher Education Student Outcomes: Policy, Practice & Research (pp.259-275). Wellington, New Zealand: Ako Aotearoa.

Hay, D. B., Tan, P., & Whaites, E. (2010). Non-traditional learners in higher education: comparison of a traditional MCQ examination with concept mapping to assess learning in a dental radiological science course. Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Education, 35(5), 577-595. doi:10.1080/02602931003782525

Hixson, R., & Hunt-Unruh, D. (2008). Demystifying HIPAA. (Cover story). Annals Of The American Psychotherapy Association, 11(3), 9-14.

Jenkins, J. O. (2010). A multi-faceted formative assessment approach: better recognising the learning needs of students. Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Education, 35(5), 565-576. doi:10.1080/02602930903243059

Rakestraw, E. (2009). One Size Doesn’t Fit All. Journal Of Legal Medicine, 30(2), 269-287. doi:10.1080/01947640902936597

Reddy, Y., & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Education, 35(4), 435-448. doi:10.1080/02602930902862859.

Tulbure, C. (2011). DIFFERENTIATING INSTRUCTION UPON LEARNING STYLES IN HIGHER EDUCATION: A CONTROVERSIAL ISSUE. Bulletin Of The Transilvania University Of Brasov. Series VII: Social Sciences. Law, (53), 79-84.

Appendix 1: HIPAA CE ARTICLE

Source: Hixson & Hunt-Unruh, 2008

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee