Evaluating the Outcomes of Vocational Education Program in Abu Dhabi, Dissertation Example

Abstract

The paper examined the effectiveness of the evaluation method currently applied to measure the outcomes of the vocational education programs in Abu Dhabi. In-depth interviews were carried out with three managers and the documents of one of the biggest vocational institutes in Abu Dhabi were reviewed. It has been found that the current trend is using basic and conventional evaluation systems. Evaluating the outcomes of the programs is done as part of other evaluation processes and is limited to closure of the program. What differentiates the vocational programs is the impact of their outcomes on the community at large represented by the employers and Tawteen Council. Therefore, the Multi-Objective Realization Approach (MORE) is proposed as an appropriate method for evaluation to be applied in Abu Dhabi Institutes. The MORE Approach will help in evaluating the effectiveness of the programs in addition to measuring their outcomes in relation to the stakeholders’ objectives and needs. The programs include delivering and assessing different types of diplomas to enhance the opportunities of local job seekers in finding jobs. By using the MORE evaluation framework, the outcomes evaluation of the programs will be extended beyond program closure. It has been found that the current evaluation method should include the number of graduates against the percentage of employment. It also should involve the competencies of the graduates against the skills required in the market. Moreover, the outcomes of the programs must include their impact the education levels. The proposed MORE method will help in increasing the possibility of achieving the strategic goals of both; the institute and its stakeholders. Therefore, this study focuses mainly on the outcomes of the evaluation methods in respect to stakeholders’ short and long term needs and objectives.

Keywords: Vocational Education – MORE – Outcomes Evaluation – Evaluation Methods

Acknowledgments: I am deeply grateful to the many professors whose wise and munificent teaching has taught me so much about my chosen field. The patience demonstrated again and again by my teachers in committing their wise instruction to me and to other pupils would do credit to any wise sage. My time in the university has transformed me from a mere novice to a student who is hopefully much less of a novice; at least I know now that learning is indeed a lifelong process. Even as the flowering plants of the desert send forth their blossoms after a rain, so too must the mind of the truly inquisitive search after knowledge and understanding, and open to it when it is found. I owe these insights to my many wonderful teachers, and I shall remain forever deeply in their debt. Far more than any specific piece of information or the like, what they have taught me is the means of acquiring true knowledge and true understanding for myself, by means of free inquiry, and a mind unfettered.

I thank also my parents. Mother and Father, words cannot truly do justice to the debt that I owe you, for your love and support these many years. I well recall how supportive you were when I stated my aspirations to go to college, and how you encouraged me to apply myself wholeheartedly to my studies, not going after vain and idle pursuits and the follies of youth. It is to you both that I owe my strong beliefs in intellectual and personal integrity, and the value of the work ethic that has taken me so far in academia. Thank you, Mother and Father, I remain eternally grateful!

Last but by no means least, to my darling fiancé: I am thankful every day to have you in my life. Your love and support throughout this entire process has often been the only thing preserving my sanity from the pressures of over-work. Had it not been for you, I think I might well have reached burnout long ago. Were it not for you, my life would be a much poorer and darker place indeed. Thank you, my dear, for everything!

Introduction

The vocational education in UAE has emerged as a resolution for Emiratis who did not get the chance to achieve a high school certification or complete their higher education. The structure and the process of vocational education programs are complex. The program involves a large number of internal and external stakeholders involved in the different phases of the program.

The process has several stages that begins with writing the proposal and ends by graduating skillful Emirate who can join the workforce. UAE endeavor is to establish a strong educational framework in order to meet the development goals of the region. The vocational training in UAE is considered and managed as higher education. The strategies are developed by higher educational council and ministry of higher education within the frameworks of the Emirate’s education policies. The program’s main strategic goal is to provide the learners with the necessary skills to be able to join the workforce of different businesses and industries. For this reason, several vocational education programs are currently running in Abu Dhabi (ACTVET Website). The success of the vocational education program will have a positive influence on the national education and employment structure in Abu Dhabi. Therefore, the five phases of project management must be applied effectively.

This study mainly focused on the control phase of project management. The evaluation strategies currently applied in the vocational education institutes in Abu Dhabi are examined. Then they are compared to The Multi- Objective Realization Approach (MORE) being an effective and practical approach for evaluating programs. It has been found that the current evaluation method is very basic and can be enhanced to provide more details about the outcomes of the programs. MORE approach has been proposed as it helps to consider the different needs of stakeholders through the use of GQM technique and constant interaction with the stakeholders. This will extend the evaluation of the programs to include their long term impact on stakeholders.

Problem Statement: Vocational education is a burgeoning field in the United Arab Emirates, where it is increasingly becoming recognized as the key to equipping the next generation of students for the workforce. In particular, vocational education is designed to equip students to meet the demand for highly technical positions, such as engineering, industry, and medicine, etc. However, there have been, and continue to be, very real problems with vocational education in the United Arab Emirates: while it is growing in popularity, it has been producing a great many students who are woefully under-qualified and ill-prepared for the field. The problem is especially acute with Emirati nationals, who are overwhelmingly drawn to the public sector, to such a degree that the government is now going to great lengths to funnel them into the private sector, especially the high-skilled occupations.

The question of what is wrong with vocational education in the UAE, and how it might be fixed, is what animates this research. This study will explore the educational system in the UAE, examining the patterns and the factors that either promote or inhibit success. Along the way, we will explore vocational education in other countries, and ascertain what does and does not work, both in the UAE and abroad. In so doing, this study will establish important information for a reform platform for vocational education in the UAE, a reform platform that may well change the character and shape of Emirati industries indubitably.

Research Question

- How effective is the evaluation method currently used to measure the outcomes of vocational education programs in Abu Dhabi?

- How to make the current evaluation method applied to evaluate vocational programs more effective?

The Aim and Objectives of the Research

The research aims to examine the evaluation method currently used to measure the outcomes of the vocational education programs in Abu Dhabi. Recommendations will be provided for a more practical evaluation approach. The objectives of the research are as follows:

- To examine the evaluation methods currently used to measure the outcomes of vocational education programs in Abu Dhabi.

- To compare the currently used methods to measure the outcomes of vocational education programs in Abu Dhabi with the MORE approach.

- To propose a more effective evaluation approach for measuring the outcomes of vocational education programs in Abu Dhabi.

Significance of the Study

The vocational education in Abu Dhabi has a considerable impact on the national education and on the employment rates. Evaluation is a significant tool for development to ensure the strategic goals are met. Therefore, this study points out the gaps in the current evaluation method used by the researched institute. It provides useful suggestion to evaluate the outcome of the vocational programs more effectively. Effectual evaluation using the proposed model, MORE, will enhance the decision making process. It will also improve the outcomes of vocational experience in relation to internal and external stakeholders’ needs. Proper evaluation will help in decreasing de-skilling and to replace proper skills in suitable positions. On the long run, this will increase the workforce outcomes and help in raising job effectiveness and productivity rates.

Research Pattern and Scope of the Study: Now the character of the research pattern was as follows: firstly, a rich literature review was conducted, a literature review that delved into the subject of vocational education programs in order to facilitate adult learning. Of the foundational insights gained and the key learning revealed, the first was the considerable importance of vocational education for the building of knowledge and the promotion of skill amongst graduates.

This much being established, the literature review did then explore the features of the educational system in the United Arab Emirates. Here, the research focused on many governmental efforts to promote vocational education, notably through the Higher Colleges of Technology (HCT). There is also the Abu Dhabi Vocational Education and Training Institute (ADVETI), and others besides. The system of vocational education has been growing in the UAE, and the HCT in particular is evincing quite considerable promise. Indeed, a key finding was that the HCT have raised their standards, with lower-scoring applicants being funneled into ADVETI.

Problems with pedagogy in the UAE educational system were identified, problems that have traditionally undercut the efficacy of the system of vocational education as far as producing graduates who are capable of being effectively competitive in an increasingly globalized marketplace for jobs. UAE efforts to ameliorate these problems have seen rather mixed success at best, and very often lackluster results. Moreover, the attraction of many Emiratis to the large public sector, and their low rates of performance in the private sector, were elaborated upon and discussed. Key problems that might account for all of this were identified, and the groundwork of possible solutions was explored at some length.

Efforts to promote vocational education in other countries were also discussed, notably the prestigious Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT). RMIT provides salutary examples indeed, and the reasons for this proved quite exciting. Indeed, RMIT points the way toward many salutary reform efforts that could be carried out to greatly improve the educational picture in the UAE.

Both the Republic of Turkey and the People’s Republic of China present cases of vocational educational systems much in need of reform, cases evincing some interesting parallels with the UAE. Mismatches between the skills of students and the demands of industry were identified as significant problems in both cases, as in the UAE, and the lack of practical experience was identified as a culprit, as is also the case in the UAE. From all of this the picture become clear indeed: the means whereby vocational education could be reformed and rendered into a form that would produce competitive graduates.

Now the scope of the research was designed to capture the picture of vocational education in the UAE: what is working, what is not working, and the reasons for each. From this it could be the more readily surmised the contours of a solution. Outside literature, literature on similar issues in other countries, was made use of to provide attestation of both similar problems and likely solutions. All of this was done in accordance with the mandate to produce a most compelling and yet concise literature review, one that would serve the needs efficaciously of the dissertation.

Project management was then analyzed most studiously, with especial care rendered unto the phase of control. The character of project management was covered, especially the foundational importance of the control phase, which is necessary that the project may be corrected in the event of any deviations.

The conceptual foundations were then established and laid down, establishing a firm focus on alternative measurement processes, and the imperatives of evaluating program performance. A firm emphasis was made on the effective management of the evaluation process, in order that value creation might be properly measured. The MORE approach was identified and chosen for the purposes of this paper, chosen and used as the foundation of a process of identification.

The institute selected was ADVETI. It was anonymized to ABC Institute for the sake of participants’ anonymity. It was selected precisely because of its great size and importance in the UAE: the reasoning was that any findings would be of relevance to the successes and challenges faced by vocational education programs in the UAE. ABC has substantial interactions with the Tawteen Council and employers, and is therefore of considerable importance in educating the next generation of skilled workers in the UAE. Problems with ABC’s evaluation of its vocational programs, if identified, could yield solutions that have the potential to substantially increase the efficacy of vocational education, and the competitiveness of Emirati graduates of these programs accordingly. The data collected were designed to do precisely this, informing a comprehensive study based on grounded theory.

A qualitative research approach was selected as the methodology, and in-depth interviews were conducted with three key and foundational people at a vocational educational institute in Abu Dhabi. The sample size was small by design, in order to enable the study to delve the more deeply into the rich storehouses of knowledge held by each of these three individuals. The institute from which these individuals were selected is ABC institute, selected for its size and importance to other institutions. The findings were used as the basis of rich and well-drawn conclusions, utilizing Grounded Theory to explore connections between categories and reduce the data. From this proceeded the findings about the evaluation methods utilized, findings which proved illuminating indeed. Finally, recommendations were issued, recommendations to guide the course of future research.

The chapters, then, are these:

Chapter 1: Introduction. Poses the research question, propounds the aim and objectives of the research, and exposits upon the significance of the study.

Chapter 2: Literature Review: Reviews at no mean length the literature upon vocational education. Vocational education is reviewed in the context of the UAE, and also in the context of other countries. Problems with vocational education in the UAE are identified, as well as areas in which it is performing better. Strengths and weaknesses of foreign approaches are also analyzed, and the findings examined.

Chapter 3: Proposed Evaluation Method: The proposed method of evaluation is examined and discussed, consisting as it does of the MORE frameworks. The character and features of these are revealed and explored at some length.

Chapter 4: Methodology. The methodology is expostulated upon, consisting as it does of interviews with three individuals selected from ABC institute. These individuals were selected for their considerable importance, as was the institution. The nature and character of the data analysis are elaborated upon. The processes of open coding, axial coding, and selective coding are examined and remarked upon.

Chapter 5: Research Findings. At last, the findings of the research are revealed, and the character of these and their ramifications for praxis elaborated and remarked upon. The evaluation process of ABC Institute is found to be sound, meet and right for the circumstances in which this institution of higher learning operates.

Chapter 6: Discussion. In light of the revelations of the research findings, a discussion is held.

Chapter 7: Conclusion and Recommendations. Wherein the paper is brought to a close, and recommendations issued for future research.

Literature Review

Vocational Education

Several researches have investigated the importance of adult learning through vocational education programs. Klein (1999) states that the higher education institutes are increasingly determined to execute inventive programs that concentrate on the real world needs of contemporaneous workers. Furthermore, the universities and colleges experience mounting competition from other educational profitable and non-profitable organizations targeting employed adults (Graves, 1997). The well-versed systematic development of innovative educational programs is essential to attract and satisfy the current adult learners who look for value and flexibility in the several available options (Meister, 2001).

Vocational education is defined as the development and the application of certain knowledge and skills required by societies for middle-level occupations. Moreover, vocational education involves general education as well as studying technologies and relevant sciences and acquiring practical skills, behaviors, comprehension and knowledge related to jobs in different sectors (UNESCO, 2001). On the other hand, King and Martin (2002) see vocational education as a “fallacy”. They explicate the vocational education and training fallacy as a challenge among planning and reality. Oketch (2007) criticizes the concept of fallacy, stating that vocational education is considered as a training that forms the foundation for future training rather than being a means to facilitate job entry. For him, vocational training leads to acquiring vocational specific skills over duration of a lifetime. In addition; vocational education is seen as a significant method for enabling community members to cope with new challenges to become productive members in their societies. Vocational training leads to social structure, integration and self-esteem (UNESCO, 1999).

The ILO Recommendation Concerning Human Resources Development: Education, Training and Lifelong Learning (ILO, 2004) move of the traditional way of thinking clarifying that vocational education and training systems need to be well developed and reinforced in order to offer proper opportunities that lead to developing qualifications and skills required for the labor market. It is highly important to organize a link between vocational education and training and the labor market in the form of apprenticeships. Moreover, the importance of the programs’ content relies in its being a main concern for some parties who think that employers have a considerable influence on the skills projected.

One of the seminal features of education in the United Arab Emirates is that it is free for all citizens, at all levels (Wilkins, 2002, p. 3). The Ministry of Education and Youth and the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research are tasked with managing the educational system, while the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs oversees vocational training (p. 3). Vocational education initiatives have been under way in the UAE since the recognition, by the middle of the 1980s, that there were not enough of the right sorts of graduates from the institutes of higher education in the UAE (p. 3). Specifically, the types of skills and knowledge in demand, particularly technical skills for industry and engineering fields, etc., were underrepresented among graduates (p. 3).

In 1988, the government responded by creating the Higher Colleges of Technology (HCT) to rectify this (Wilkins, 2002, p. 3). The HCT seek to promote vocational education to equip students to be able to take advantage of job opportunities in a wide array of scientific and technical fields. To this end, they offer courses in “business, information technology, engineering, communication technology and health science” (p. 4). The HCT have produced very promising results, with some 89% of the students who graduated from them in 1999 and 2000 going on to further education or gaining employment (p. 3). Growth of the HCT has been precipitous: while in early years they attracted enrolment of only a few hundred, in 2003 they attracted nearly 15,000, and that number has since grown to over 20,000 on 17 campuses (Elsner & Horton, 2008, p. 151; Higher Colleges of Technology [HCT], 2011). Demand for post-secondary education is high, with 95% of female and 80% of male graduates from secondary education pursuing tertiary education of some kind (Darraj & Puller, 2009, p. 68). The government is responding with increasing support for education, especially higher education: for example, in FY 2010, the government allocated approximately 22.5% of the nation’s budget to the education sector (ICEF, 2013).

In 2007, Abu Dhabi established the Abu Dhabi Vocational Education and Training Institute (ADVETI) for the purposes of advancing the cause of vocational education (Secondary Technical School [STS], n.d.). A major initiative ADVETI has unrolled is the establishment of technical high schools in order to prepare students for the highly skilled fields in which there is so much demand. Students are recruited from those who have obtained their Grade 9 Certificate, and are then put through grades 10, 11, and 12. Students must also pass an entrance test in English and Mathematics (STS, n.d.).

As Swan (2012) explains, ADVETI has recently moved to expand its ranks, particularly since HCT has raised its standards for admission. Those students who cannot meet the standards set at the HCT are now offered admission to ADVETI instead. As Swan explains, the result has been a precipitous expansion of ADVETI, which has “opened three new campuses, in Sharjah, Fujairah and Ras Al Khaimah” (2012). There is also the Institute of Applied Technology (IAT), which was founded by royal decree in 2005 to provide vocational, technical education at the secondary and tertiary levels (Institute of Applied Technology [IAT], n.d.). The IAT also includes “higher learning start-ups in aviation, logistics and nursing” (n.d.).

Given the historically low rates of participation of Emirati nationals in the private sector, it is particularly notable that of the HCT graduates of 1999 and 2000 who went on to become employed, some 60% of them took employment in the private sector (Wilkins, 2002, p. 4). The HCT have outperformed UAE University in terms of the frequency with which employers hire their graduates: 68% of large firms in Dubai recruit HCT graduates with some regularity; the figure for UAE University is 50% (p. 4). A number of private universities have also been established in recent years, such as the University of Sharjah, the American University of Sharjah, Al Bayan University, and Dubai Polytechnic (p. 4). The case of Dubai Polytechnic is of particular interest, given that the emirate created the school in response to a great deal of market and industry data which indicated a need for better vocational education to help young residents of Dubai gain the qualifications needed for skilled jobs in technical fields (pp. 4-5). Though established by the government, the goal for Dubai Polytechnic has always been for the university to become an independent, private entity, something achieved by means of a process of privatization (p. 5).

The challenges for the education system of the UAE have been immense. Before the oil boom of the 1970s, the economy depended upon subsistence agriculture, pastoralism, pearl diving, and a certain amount of trade (Raven, 2011, pp. 16-17). The oil boom fueled precipitous economic growth, and the task that has befallen the UAE since has been to transform their workforce in order to produce the kinds of skilled, highly-trained workers in demand in modern industries (p. 16). Education is foundational to this, particularly the HCT. Here, however, there are a number of pedagogical concerns: according to Raven, the education system is working to update models of pedagogy and implement more modern teaching methodologies (p. 17).

While the education system has traditionally relied on teachers from Egypt and other Middle Eastern countries, typically for cultural reasons, policymakers have begun to hire Western teachers to facilitate the modernization of the education sector (Raven, 2011, pp. 16-17). Another key change is student-centered approaches to pedagogy, which are being introduced to replace traditional models, which rely heavily on rote-learning (p. 17). The goal of these approaches is student autonomy and the promotion of independent thought (p. 17).

According to Gonzalez, Karoly, Constant, Salem, and Goldman (2008), there are a number of initiatives under way to facilitate vocational education in the United Arab Emirates. Faced with declining enrollment, UAE University in particular has responded with efforts to improve its programs by linking them with practical, real-world experience for the students (p. 125). A case in point is UAE’s internship through the College of Engineering, which is designed to allow students the opportunity to work for both domestic and foreign companies (p. 125). The internship has placed students not only with Emirati companies, but also with major international companies based in such countries as the United Kingdom, France, Sweden, Finland, and Italy (pp. 125-126). In addition, UAE University has collaborated with technology parks, and even with the military, which has provided a number of Emirati students with engineering internships (p. 126).

The UAE’s two other public institutions of higher education, HCT and Zayed University, have both become actively involved in vocational education as well (Gonzalez et al., 2008, p. 126). HCT is especially well-placed to do this, given that the university was founded to educate students with the highly technical skills in demand in the oil sector and other, closely related industries (p. 126). HCT also offers foundation programs, including: “courses in English, mathematics, and other basic subjects [in order] to support the transition to programs within the university” (p. 126). Zayed University, on the other hand, follows the mold of international liberal arts universities, and as such the school certainly has a quite strong emphasis on research and outreach (p. 126).

The respective education councils of both Dubai and Abu Dhabi have played key roles in helming efforts to improve vocational education in the United Arab Emirates (Gonzalez et al., 2008, p. 128). Both have been given the mandate of directing efforts across all of the emirates, unifying a variety of approaches in a format that invites participation from both public and private sectors (p. 128). The seminal imperative is to increase the ability of the universities to provide the type of vocational education that will facilitate meeting the demand in the labor market for human resources in specialized fields, as seen (p. 128).

In Abu Dhabi, one particularly prominent and promising initiative to promote vocational education is CERT, founded as an offshoot of HCT (Gonzalez et al., 2008, p. 130). CERT constitutes an international academic partnership, one that involves both academic institutions and multinational organizations concerned with technology and business solutions (p. 130). Working together, these institutions and organizations seek to promote research in the UAE, as well as provide the necessary vocational education for Emiratis along the way (p. 130). Those who graduate from CERT receive both a degree from CERT and a degree from whichever international academic institution they have worked with, increasing their employability in both the UAE and other nations (p. 130). Abu Dhabi is also producing its much-anticipated Education and Research City, “a nexus of learning consisting of a primary/secondary school, college or university, research center, and convention center with an attached five-star hotel” (p. 130). The goal of Education and Research City is indeed research, research of the highest quality: the idea is to attract the very best faculty by providing the best research facilities possible (p. 130). Available to both Emirati and international students, Education and Research City is projected to provide a great deal of academic and vocational opportunity (pp. 130-131).

The policy of Emiratisation is a major reform platform for vocational education in the United Arab Emirates (Gonzalez et al., 2008, p. 131). The goal of Emiratisation is to bring more Emiratis into the workforce, thereby making for a workforce with higher rates of participation from Emirati nationals (p. 131). By so doing, the United Arab Emirates hope to become free from undue dependence on foreign nationals in the labor force. In particular, the goal of Emiratisation is to increase the share of jobs held by Emirati nationals in the industries of “oil and gas production, banking, insurance, trade, and, more recently, tourism” (p. 131). A significant part of Emiratisation consists of efforts to lure Emirati workers from the public sector to the private sector (p. 132). Lucrative government benefits in the public sector have been a major stumbling block here, with many Emirati nationals not attracted to the private sector due to a lack of such benefits there (p. 132). In September 1999, a new national pension law was drafted to rectify this: the new pension law states that Emirati nationals are now eligible for participating in a national pension plan even if they hold jobs in the private sector (pp. 132-133). In particular, such benefits as “government employee retirement benefits, disability benefits, life insurance, and end-of-service bonuses” are all eligible for transference to the program for those that take private sector jobs (p. 133).

According to Janardhan (2011), although the private sector creates the majority of the jobs in the UAE, Emiratis who are employed in the private sector resign at the remarkable rate of 10% per year (p. 98). Low wages are one common complaint, particularly since the opportunities in the public sector are so lucrative (p. 98). Another problem is a lack of vocational education, and the opportunities Emiratis need to improve their skills (p. 98). Still another problem is that non-Emirati employers in particular, who dominate much of the private sector in the UAE, hold negative stereotypes of Emirati nationals (p. 98). This in turn, coupled with Emiratis’ low rates of participation in the private sector, contributes to a lack of trust between Emirati employees and their employers (p. 98). Quotas are one way the UAE government is seeking to promote Emiratisation: companies which employ more than fifty employees must hire a work force that is at least two percent Emirati. Companies with over one hundred employees are required by law to hire only Emiratis as public relations officers (PROs) (p. 98).

The problem is fundamentally not a lack of opportunity (Janardhan, 2011, p. 100). Emirati nationals have plenty of opportunities for jobs in industry and engineering. In particular, a high turnover due to retirement is expected in the energy sector, with about half of those employed in said sector probably looking to retire by 2015 (p. 100). Despite the plethora of opportunities, less than one quarter of Emirati college students are majoring in science and technology (p. 100). Instead, they have gravitated to business in droves: over 64% have opted for business school (p. 100). Both business and banking are preferred to industry and technology “because the qualification requirements are less rigorous, and promotions are easier in comparison” (p. 100).

Still, promoting education is likely to go a long way towards redressing this imbalance in the number of Emiratis employed in engineering, industry, and the like (Shalhoub & Al Qasimi, 2006, p. 106). By providing the necessary education and skills, students will be in a better position to pursue opportunities in these fields. And, too, the success of some students can readily be expected to inspire others to attain qualifications in these fields (p. 106). Overall, the schools are held to be the necessary platforms for advancing technical vocational education in the United Arab Emirates. In fact, the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company has a Career Development Center, which is specifically geared to helping the hundreds of Emirati students who do not complete secondary education (p. 106). At the Career Development Center, these students take courses to qualify for technical positions within the oil industry, a very promising sector in the United Arab Emirates indeed (p. 106). There is also the Emirates Institute for Banking and Financial Studies, which provides the necessary training for job opportunities within the financial sector (p. 106). This institution, too, is expected to be a major part of the drive to implement Emiratisation through technical education (p. 106).

Nursing education in the UAE is also in need of initiatives to enhance the quality of vocational education provided. As Nematollahi and Isaac (2012) explain, the performance of the nursing program in Dubai has been lackluster indeed. Dubai’s graduate nurses tend to be unprepared and ill-equipped, and many report not receiving enough practice in the clinical setting in order to feel ready to practice after graduating (p. 194). Accordingly, the Graduate Nurse Program (GNP) was designed by the Professional Development Center (PDC) to provide nurses in training with the opportunity to develop the important competencies needed to practice successfully (p. 195). This is the more important since the position, once realized, comes with so much stress, and many, many nurses do indeed feel unprepared (p. 195).

The PDC identified important functions necessary to a successful program of vocational education for Dubai’s nurses (Nematollahi & Isaac, 2012, p. 195). Firstly, they ascertained the importance of certain management tools and special indicators, together to serve as the means of signaling an early warning in the event that things were not transpiring as they were expected to (p. 195). Secondly, what was needed was also a system for cultivating the important capacities in the training nurses (p. 195). Thirdly, the PDC identified the recruitment and retention of nurses as an important point. And fourthly, the PDC ascertained the importance of establishing a support system to help newly-qualified nurses by ameliorating the stress to which they were subjected (p. 195).

The program was delivered over the course of one year, and rotated the nurses-in-training throughout the various aspects of their future jobs (Nematollahi & Isaac, 2012, p. 196). Particular care was taken to match the difficulty level of the work with the students’ own level of competence, so that they were not left overwhelmed by the material (pp. 196-197). Overall, the emphasis is on “supporting new nurses in their working environment”, such that they are able to discharge their duties and adjust to the stressors of a demanding environment (p. 197).

The first step for the program is a good solid orientation, designed to welcome the new candidates into the embrace of the program (Nematollahi & Isaac, 2012, p. 197). New entrants are required to learn the organizational fundamentals, including the underlying and overarching philosophy, values, vision and mission, and the character of the organization: where they are to fit in it, and what they will be expected to do (p. 197). Refreshing skills is another function of the orientation: after all, transitioning from theory to practice can be complex, and often requires relearning some of what has been learned (p. 197). Entrants also have to learn important organizational processes, i.e. what to do, when, and how (p. 197). By so doing, the new entrant can be oriented within the structure of the organization, made aware of their place within its great connective tissue and social ecology.

Communication and a good support network are another important part of the process (Nematollahi & Isaac, 2012, p. 197). A key strength of the GNP is the fact that it surrounds new clinical nurses with several people who are tasked with helping them to adjust to the requirements of the organization: thus, they have several pairs of eyes on them, and several pairs of hands to assist them in the performance of duties, and learning the appropriate protocols and procedures, etc. (p. 197). A mentor is also assigned, to provide special instruction in the character of the job and the organization (p. 197). This gives the new nurse some important one-on-one interaction with a specific team member tasked with integrating them into the strategic plan of the organization (p. 197). Concerning the qualities and virtues requisite of a mentor, Nematollahi and Isaac elaborate that they must be “approachable, good listeners, respectful and deserving of respect, interesting, trustworthy and encouraging” (p. 197). They must also be good at reasoning, capable of divining the answers to problems and challenges, in order to facilitate the progress of those whom they mentor (pp. 197-198).

The figure of the preceptor stands large, above even the mentor (Nematollahi & Isaac, 2012, p. 198). The guardians of the program, the preceptors divine the means of reducing turnover (p. 198). By example they serve as tutelary role models, guides for new graduate nurses through the often-confusing and challenging paths they must face in adjusting to their duties (p. 198). The preceptor is interactive and dynamic, attenuated to the strategic plan on the one hand and the individual level on the other. The preceptor’s perspective enables them to direct, coach, guide, lead, and show the way to many first-time nurses (p. 198). Of foundational importance it is, then, that the graduate be able to gain access to the preceptor’s wise presence by means of regular meetings (p. 198). By this means the two may establish a ready rapport, enabling a productive tutelage (p. 198). Upon the preceptors, then, rests the means of great success for the totality of the GNP (p. 198).

Beyond doubt an excellent example of successful vocational education is the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT). This institution has undertaken a number of efforts to develop successful programs of vocational education, and the results provide salutary examples indeed (Abanteriba, 2006, p. 284). Its program of activities is titled the RMIT International Industry Experience and Research Program (RIIERP), founded in 1992 to prepare students to develop the skills needed to compete in an increasingly globalized world (pp. 283-284). The program has entailed the establishment of a number of links between the school and industry-leading companies, companies capable of offering vocational training and research facilities of the very highest quality (p. 284). Every year, RMIT selects about 160 students to engage in these programs (p. 284).

Indubitably, the goals of the RMIT International Industry Experience and Research Program are a blueprint for success. Of the goals, the first is global employability for all graduates: graduates must have a worldly, cosmopolitan outlook, conducive to flexible adaptation to a variety of diverse workplaces (Abanteriba, 2006, p. 285). Graduates must have a critical, well-informed perspective on the international workplace, in order to be able to assimilate themselves to the demands of a variety of business cultures worldwide. The second goal is to provide all graduates with vocational experience, in the form of industry-specific projects in international companies (p. 285). Here, the purpose is to give them hands-on training learning their jobs in a culturally diverse context. After all, different cultural environments have different work ethics and different rules of doing business (p. 285).

Graduates must be pragmatic, acquiring the knowledge they need as they find that they need it, in order to facilitate their employability in the globalized workplace (Abanteriba, 2006, p. 285). Realistically, graduates must also be liberal in their sentiments and sensibilities, comfortable interacting with people from diverse cultural backgrounds without reservation or judgment (p. 285). And moreover, graduates must also be civic, conducting themselves as good ethical citizens of the globalized business world and its workplaces (p. 285). But of a surety, this is important in any workplace; nonetheless, in the international, globalized workplace it comes with certain requirements for cultural awareness and knowledge about correct and incorrect conduct (p. 285).

The third goal of the RMIT International Industry Experience and Research Program is the provision of facilities that are diverse in type and kind, that the students may profit from a comprehensive and ecumenical educational experience (Abanteriba, 2006, p. 285). Only by so doing may they hone their skills to the utmost, becoming versatile and dynamic employees capable of participating effectively in a strategically-oriented organizational culture. The fourth goal is for RMIT itself to cultivate the means whereby it can assess how well it is providing for its students’ education (p. 285). This goal is concerned with metrics: the university must take stock of what it is doing, and ensure that it is facilitating a sound experience of vocational education for all of its students. In particular, the students must be able to cultivate a global perspective, and the university must ascertain that it is helping them to do so (p. 285). The fifth goal is the promotion of interactivity and collaboration: RMIT must collaborate with companies and with institutions possessing the best resources of knowledge and capacity in order to maximize the learning opportunities for RMIT’s students (p. 285). By so doing, it can fulfill its educational mandate to the utmost (p. 285).

Indubitably, the success of RIIERP was made possible by very careful planning, and by involving all of the relevant stakeholders (Abanteriba, 2006, p. 286). By so doing, RMIT was able to demonstrate to each of the relevant stakeholders the very real benefits that could be accrued unto them by participating in the RIIERP. Of utmost and foundational import was the selection of student participants, a task which required care and skill. Firstly, student participants are selected according to academic ability, with their performance constituting up to 60% of the points required for admittance to the program (pp. 286-287). Secondly, students are interviewed, with the interview constituting up to 40% of the points necessary for admittance into the program (p. 287). In particular, the interview is used to establish that the student possesses the knowledge concerning the goals of the program, and what it is and is not intended to do—and what is expected of the participant, what duties they are to discharge (p. 287).

Taking into account the student’s own ardor for the program is another key factor, one that must also be measured and ascertained: the student must be committed to discharge their duties and act in accordance with the responsibilities entrusted to them (Abanteriba, 2006, p. 287). Students must also be capable of articulating their own reasons for their choice of company: why they wish to intern there, and what they hope to gain from the experience (p. 287). Of especial importance, the student must be able to articulate those favorable features of the company felicitous to their own career aims, and therefore to vocational training (p. 287). Having been selected, the candidate is initiated: a series of special sessions enables them to learn and internalize the nature of the company’s work culture and expectations (p. 287).

To be sure, the benefits for the students are considerable, and communicating this to them has helped to ensure the most efficacious results (Abanteriba, 2006, p. 287). Early exposure is one: the vocational educational opportunities of which they are availing themselves by participating in the program help them to develop an especially competitive curriculum vitae, one that will serve them in good stead when they go to seek employment (p. 287). Students can work in these companies from 3 to 12 months, and gain valuable experience in on-the-job training (p. 287). While they can learn a great deal about the technical aspects of their jobs, students can also learn much about the opportunities and challenges of working in a culturally diverse setting (p. 287). Taken together, these opportunities can greatly improve the employability of the participant once they graduate and enter the job market (p. 287). In fact, up to 10% of participants are offered jobs by the very companies with which they interned, often many years later (p. 278).

If the benefits for the students are considerable, so too are the benefits accrued to the university. As Abanteriba (2006) pointed out, the cardinal charge of a university is to provide its students with a rich, fulfilling, comprehensive and ecumenical educational experience (p. 288). The logical way to do this is to provide them with opportunities to learn and develop the skills that they require to compete successfully in the global marketplace for work (p. 288). By so doing, the university can increase its prestige and reputation, thereby attracting more funding, the best teachers, and the best students (p. 288). In other words, this is a win-win scenario for students and university both. The university greatly enhances its programs by providing these advantageous and felicitous opportunities, and this enables it to maximize its ability to complete its educational mission (pp. 288-289).

Education of the student-participants also provides benefits to the participating institutions and organizations (Abanteriba, 2006, p. 290). These efforts can indeed be placed in a strategic context, as part of the grand strategy of the participating organizations to cultivate and retain new talent (p. 290). Without committing to hiring these students, companies nonetheless have the opportunity to observe them and teach them, an invaluable opportunity to help cultivate new talent for the labor force (p. 290). One invaluable opportunity for the companies is the opportunity to see how well students are learning from their universities. This can in turn help companies to calibrate training requirements for entry-level positions in particular accordingly (p. 290). This positive feedback cycle is much to the advantage and interests of all parties concerned, inasmuch as it addresses the needs and desires of all stakeholders.

Sometimes the companies are in a position to provide helpful feedback to the university, which can then move to improve its program, and therefore the quality of the graduates it turns out—graduates who may some day work for the companies in question (Abanteriba, 2006, pp. 290-291). For example, a number of companies commented that RMIT students tend to be monolingual, an undesirable state of affairs in an increasingly globalized workplace (p. 291). The university responded, ameliorating the problem by introducing courses in several European and Asian languages (p. 291). But companies also gain a great deal practically, in the course of their day-to-day affairs, by participating in the programs: they gain the contributions of the students, which are often quite significant. Those organizations that have participated in the programs have evinced a very real appreciation of the skills that the students possess, and the contributions that the students are therefore able to make to the operation of business within the organizations (p. 290). The students bring fresh ideas and new sets of eyes to examine problems, thereby enabling the companies to be that much more competitive (p. 290).

Similar efforts to establish partnerships between universities and companies are under way in the Republic of Turkey. According to Adiguzel (2008), such collaborations still have a long way to go. Although an estimated 62% of industrial enterprises engage in such collaborations with universities, cooperating in order to facilitate vocational education for engineering students, and students in other highly specialized technical fields, the partnerships are geared largely towards essentially basic areas of the enterprises (p. 34). Adiguzel lists such basic areas as “test-measurement services, nomination of an expert, possibility for scientific publications, problem analysis, improvement of human-machine systems at a micro level, and solution to the quality-related problems” (p. 34). Overall, organizations are less inclined to want to establish meaningful partnerships with universities for the purposes of educating the next generation of students, and more inclined to simply partner with them in order to buy certain very basic services from them (p. 34). This is in sharp contrast to the situation as described with RMIT, and in many European Union countries, wherein universities collaborate with major, leading companies in the industries for the purposes of meaningful vocational education for the students (p. 34).

Adiguzel (2008) found many problems with extant systems of vocational education in Turkey, though many of the problems suggest rather obvious solutions. Overall, the first problem identified was poor legal substructure: case in point, the lack of insurance against accidents for the engineering students in training (p. 38). They are not protected against the many risks they face, thanks to a lax regulatory environment that does not even constrain businesses from considering the number of other workers they have on hand when taking on students (p. 38). If businesses were forced by regulations to keep the ratio of workers to students high, with more workers as a percentage of total workforce, this would of course reduce the likelihood of accidents and other mishaps, as well as enhance the opportunities for students to learn and gain a good education (p. 38). But students are generally much cheaper than regular workers, so a business that takes on many students may, of course, be able to cut costs—a powerful incentive for a business to participate in a way that is less than ethical (p. 38).

The second problem identified by Adiguzel (2008) was a lack of effective communications between universities and businesses (p. 38). Poor communication meant poor flow of information, which greatly hampered the educational experience for the students overall (p. 38). There were not even established channels of communication, protocols and procedures designed to facilitate communication between the enterprises and the university (p. 38). Another finding: faculty members believed that enterprises took on trainees due to being cajoled or even forced by faculty and/or students, as opposed to being a function of supply and demand (p. 38). Clearly, better communication and better knowledge is needed to facilitate a better system of vocational education in the Republic of Turkey.

Many different types of Turkish enterprises provide vocational educational opportunities, something which, while it might sound beneficial, actually carries problems of its own (Adiguzel, 2008, p. 38). Some were unquestionably more effective than others, case in point incorporated companies and holding companies (p. 38). Institutional companies were the most promising in their proclivity to work with the universities in order to gainsay student participation and evaluate performance (p. 38). However, small-scale enterprises were better at providing actual industrial education, due to these companies being quite selective and having very limited trainee student quotas (p. 38).

Another problem: lack of adequate controls for the education that was provided (Adiguzel, 2008, p. 39). It is of great importance indeed that the industrial education provided by enterprises be of suitably auspicious quality and subject to examination for relevance (p. 39). Control must be exercised to ensure quality of the education provided for the students (p. 39). The processes pertaining to feedback were lacking also, inasmuch as these were characterized by a lack of preparation, and the feedback was oral only (p. 39). Insufficient was the time allotted towards the preparation of documents establishing in writ the nature and character of the feedback to be provided, and thus the means by which the students might advance themselves unto greater heights of learning and excellence in the cultivation of their faculties and skills in the fields of their choice (p. 39).

To wit, from all of this it may be the more readily surmised that a system of practical directives, diligently and scrupulously applied, must needs have served for the amelioration of all diverse assorted sundry problems identified (Adiguzel, 2008, p. 39). Insufficient directives and feedback constitute a lack of proper and appropriate channels of communication, that most foundational of imperatives for the passage of information in an efficacious manner, designed to facilitate the ready working and sound operation of the competitive, strategically oriented organization. Clearer directives would have enabled the students to achieve adequate preparation by learning from mistakes and correcting and improving their conduct as they went along; the lack of these is the salient issue demanding resolution (p. 39).

The final issue identified was insufficient time for the internships: the students did not have adequate time to cultivate their skills and profit thereby (Adiguzel, 2008, p. 39). Rectifying this would enable them to achieve true mastery of their skills, true excellence, and in so doing to become the more competitive in the international workplace (p. 39). The time allotted unto the students was either two periods of thirty days’ each, or else three periods of twenty days each. This time, put plainly and forthrightly, was found to be inadequate entire for the development of the professional virtues needed to ensure mastery of the disciplines (p. 39). Longer time is needed for the apprenticeship, that the interns may profit from the opportunity and master the knowledge on offer. The rectification of this lack would serve a great deal to remedy the deficits of vocational education in the Republic of Turkey (p. 39).

Remedying the problems with the regulatory environment would require efforts to lend puissance and strength to the legal substructure of industrial education (Adiguzel, 2008, p. 40). By so doing, the safety of the students may readily be assured, and the experience of education made the more profitable throughout. Insurance is foundational for assuring safety. Enterprises should also have to take into account the number of their employees when taking on trainees; this too would, to be very sure, improve their efficacy with regard to vocational education (p. 40). Thus, a sound regulatory environment is the solution proffered to the first problem identified by Adiguzel (2008).

Secondly, students must be adequately prepared for industrial education (Adiguzel, 2008, p. 40). A system of coordination, Adiguzel claims, would go a long way towards rectifying the problems with regard to preparing students for industrial education: such a system could be used “to classify the firms according to their job areas, to establish a relationship between the enterprises and students, and to control the appropriateness of education in enterprises to the goals” (p. 40). Such a system of coordination would ensure the overall success of the process: without an adequate system of coordination, it is no wonder that vocational education in Turkey has been subject to a great deal of inefficiency and a great many problems.

Protocols of cooperation would also greatly expedite the process of industrial education (Adiguzel, 2008, p. 40). Larger firms should be prioritized for giving industrial education, since larger firms generally have human resources departments accustomed to heavier turnover, and which are the more efficient and therefore much to be desired (p. 40). Competence must also be established for the partnership to succeed: it must be established which competences the graduates will be required to master, and what skills in which they must be proficient (p. 40). Once this is established, the curricula and all attendant educational programs can be reworked at need around these criteria (p. 40).

Adiguzel (2008) recommends also that on-site inspections be established as a matter of course, with standard protocols and structures to guide them (p. 40). The physical conditions of the workplace, after all, are of considerable importance, and care must be taken to ensure that they are entirely meet and appropriate for the process of vocational education (p. 40). Regular meetings must be established as a matter of course. These meetings should involve the student, the teacher(s), and the people involved with the student in the process of vocational education on-site (p. 40). The likely benefits are obvious: more learning for the student, and generally better coordination between all stakeholders (p. 40).

Finally, a longer time period is a fairly common sense measure to be taken: more time would allow the students a longer period in which to learn new things and apply those skills (Adiguzel, 2008, p. 40). This in turn would increase their marketability once they are looking for employment. Adiguzel recommends increasing the length of time for the total education of an engineering student from four to five years, thereby freeing up time that can then be utilized for research specialization, case in point, vocational education by means of participation in a company (pp. 40-41).

Concerning vocational education in Turkey, and the prospects for the reform thereof, Nursoy (2008) analyzed the prospects for applying a certain system of vocational training developed in the EC and the USA to Turkey (p. 603). This system is technology engineering, long established in the advanced Western democracies but completely new to Turkey (p. 604). Nursoy took a survey of 64 companies in Ankara, each of which employs more than 30 employees (p. 606). What Nursoy ascertained was that inadequate consideration was given to the all-important functions of research and development (R&D) by the small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) (p. 606). By comparison and contrast, the larger enterprises typically had an active R&D program, or else a product development department (p. 606). The explanation for this is relatively simple: SMEs are typically engaged in the production of products which are purchased by larger companies, whereas the larger companies must develop the products needed to compete in the global marketplace (p. 606).

Nursoy also found that many companies had complaints about the technical qualifications, or lack thereof, of the people they hired, new graduates from Turkey’s technical high school and vocational higher school (p. 606). According to Nursoy, a decrease in enrolment is hurting these schools, and making for a lower quality overall (p. 606). In particular, the technicians are inadequate for their poor analytical and problem-solving abilities, lack of communication skills, and finally poor manual skills (p. 606). How to explain such abysmal results? The key problem, Nursoy reveals, lies in a mismatch between the nature of an engineering education in Turkey, and the actual requirements of a real engineering workplace in industry (p. 607).

In general, an engineering education in Turkey is oriented towards science, and soundly grounded in theory, though much less so in practice (Nursoy, 2008, p. 607). As a consequence, graduates of engineering schools emerge with heads full of theoretical and scientific knowledge, but little of the sort of practical experience necessary to build real skills in their chosen field (p. 607). This is a problem in the industry, where engineers are expected to have precisely these skills, in order to run manufacturing systems and carry out associated, attendant processes (p. 607). Engineering work often requires good teamwork, and very few engineers work in the research and development field (p. 607).

These problems are considerable, but the solutions proposed by Nursoy (2008) are elegantly simple. Of the most seminal importance is the modification of certain institutions to improve the training of technical teachers, so that they are in turn equipped to train new crops of engineers in precisely the sort of practical knowledge needed to meet the requirements of the industry (p. 608). The proper training of technicians can be affected precisely by altering the curricula of the technical high school system in order to facilitate hands-on, practical training that gives students the sort of applied knowledge they will need if they are to succeed (p. 608). By so doing, Turkey can indeed acquire a system of engineering education capable of training competent engineers.

Appropriate curricula constitute an important dimension of vocational education as well. Should the curriculum not adequately promote the development of the requisite skills and capabilities for the field, the student will be left the worse, ill-prepared to confront the complex demands of an active workplace in a technical field. It is therefore of the most foundational and paramount importance that the curriculum be well-informed and informative, conducive to the acquisition of the needed knowledge. Perhaps nowhere is this more important than in the health industry, as Clase (2008) reveals: in pharmaceuticals and in biotechnology, innovative scientific discoveries are pushing forward the frontiers of knowledge in the most precipitous and transformative fashion, precipitating a corresponding and concomitant need for a new crop of highly skilled and well trained young people to fill positions in the life sciences (p. 12). With products and services on offer in the industry ever more sophisticated, ever more wondrously complex, it is absolutely essential that the students possess the knowledge needed to master the discipline in question (p. 12).

In an effort to address the educational needs of students planning to enter such biotechnology fields, Purdue University is leading the way with a new academic minor: Biotechnology (Clase, 2008, p. 13). This minor is the result of a fruitful collaboration between the Colleges of Pharmacy, Science, and Technology (p. 12). The goal of this educational endeavor is to promote the appropriate knowledge by means of a laboratory environment that is interactive, wherein students can engage in research and acquaint themselves with the scientific processes so necessary and foundational to their jobs (p. 13).

A number of actionable, concrete goals have been articulated for this curriculum, the first being to increase the students’ facility with the subject matter (Clase, 2008, p. 13). This is, of course, necessary that the student may understand the requirements of the field, and the nature of the incredibly complex, skilled work to which they are called. The second goal is instruction in the development of scientific reasoning (p. 13). This is done, that the mind may be equipped to set itself unto whatsoever tasks the student may be confronted with: scientific reasoning will facilitate the surmounting of problems and the removal of obstacles of all kinds. To wit, scientific reasoning is a kind of ‘meta-tool’ which facilitates more efficacious operation throughout (p. 13).

The third goal is the promotion of an enhanced comprehension of the oft-mysterious complexity and ambiguity of the work to which the student is devoted (Clase, 2008, p. 13). After all, such work is often very complex, very ambiguous, and loaded with many variables and uncertainties: resolving this, peering through the swirling phenomena in order to augur that which is needed is a skill of the most profound importance (p. 13). The cultivation of practical skills is another goal: after all, the student will need many practical skills, a panoply of them, in order to successfully pursue a career in the life sciences (p. 13). Promoting a greater awareness and understanding of the nature and character of the scientific enterprise is another goal: the student must cultivate their mind in a scientific manner, becoming transformed in the nature of their thought processes such that they may understand the true character of science (p. 13).

With understanding, too, must come interest: a true interest in science, and that which it can reveal and make known (Clase, 2008, p. 13). The promotion of an interest in science, then, is another goal of the most profound and foundational importance (p. 13). Finally, the promotion of teamwork abilities is the final key goal to which the curriculum is devoted, and about which it is built: that the student may master the crucial social skills necessary to work with other students in a research and laboratory setting (p. 13). By promoting all of these goals, the university may realize its goal of initiating a new crop of students into the field, having more than adequately prepared them through vocational education for what lies ahead (p. 13).

The biotechnology program at Purdue University, then, is a good example of what can be achieved in vocational education with a sound strategic plan to guide the educational process: a curriculum that is designed to enhance knowledge, understanding, and interest (Clase, 2008, p. 13). The goal is very much to promote the development of the skills needed to do research correctly and well: the higher order thinking, the devotion to research and inquiry, all of which makes possible a great deal of learning (p. 13). This prepares the student to be competitive in the workplace, able to surmount the challenges that lie ahead. Unsurprisingly, this program is an integral part of the grand strategic plan of Purdue University: through the promotion of interdisciplinary collaboration, it facilitates the strengths of the university in the life sciences and in technology, positioning students to make their own contributions to biotechnology (p. 13). For technology and life sciences, the focus is on providing the opportunity for the student to engage in hands-on research (p. 13). The particular applications singled out are genomic, proteomic, and bioinformatics (p. 13).

Such a linkage between education, industry, and enterprise is precisely the way to reform vocational education in order to facilitate an effective program. Indeed, writing on the need for reform in Computer Application Technology (CAT) in China, Qiming (2012) points to this tripartite linkage as foundational. According to Qiming, there are two key problems in higher vocational education in China today: some cross-section of the student body consists of apathetic students, students who have little interest in their courses and even grow tired of learning (p. 147). This leads to poor results indeed, as the students are not sufficiently motivated and therefore do not take the initiative in studies and get poor grades (p. 147).

A second problem is similar to that elaborated upon by Nursoy (2008) for Turkey: a severe mismatch between what graduates know how to do, what they have learned, and what employers actually want (Qiming, 2012, p. 147). Qiming identifies a number of causes for this, the first being that higher vocational colleges in China attract many students who are very poorly-performing students with little motivation to improve (p. 147). Secondly, the course materials themselves are often too difficult, at least given the caliber of students they typically attract (p. 147). Moreover, the pedagogy leaves much to be desired, since courses are typically taught in a manner not unlike that of undergraduate and vocational colleges (p. 147). Finally and perhaps especially egregiously, courses related to students’ majors are simply not geared toward the requirements of the market: they do not reflect demand at all (p. 147).

The path to reform begins with proper emphasis on the correct application-oriented talents needed to succeed in the marketplace (Qiming, 2012, p. 148). To do this, it is necessary to orient majors toward the actual requirements of the field: majors must be strategically aligned to prepare students for the requirements of the positions they hope to hold (p. 148). Market analysis should be conducted accordingly, in order to ascertain what skills truly are in demand (p. 148). By these means, China can programs that breed success, by equipping students with the very competencies and skills needed to succeed in the market (p. 148).

In addition to market data, Qiming (2012) suggests, interviews with the students should be used to guide the way as well: the schools need to know how capable the students are, and what are their knowledge and practice needs (p. 148). By so doing, the school can ensure adequate preparation of the students from the curriculum (p. 148). Qiming also recommends a Major Guidance Committee, one tasked with determining requirements for the students and how to carry out these requirements in practice (p. 148). Qiming gives an example of how this system could be applied to the CAT major in Wenzhou Vocational & Technical College in Zhejiang Province: information from the IT industry, including from software and cartoon associations, should be used to start with (p. 148). Given the presence of an Information Management Major on campus already, the CAT major is more focused on “network maintenance, multimedia technology and software programming as cultivation content” (p. 148). Additionally, the strongest demand for IT in Wenzhou City is for middle-level talent (p. 148). The next step is the students, who fall into two types: firstly, “senior high college graduates, who are good at logical thinking and have good study habits but poor practical skills,” and secondly, “secondary vocational college graduates, who are weak in logical thinking but strong in practical skills” (p. 148). The Major Guidance Committee can then carry out its summary analysis of the directions in which the major should be aimed: what should be required of the students, and how they should be taught, etc. (p. 148). Realistic aims must be developed: indeed, this is a crucial aspect of this phase (p. 148). In so doing, the reform effort based on tripartite linkage may successfully be realized, enabling the CAT major to turn out truly competitive and industry-responsive graduates (pp. 148-150).

Definitions of Project Management

Project management in defined as being the use of knowledge, skill, tools, and techniques for planning activities to meet project necessities. Moreover, the quality projects are defined as the ones that result in high quality products and services within the time limit and allotted budget (Project Management Institute, 2004). Similarly, Tinnirello (2000) describes project management as the knowledge, tools, and techniques used to control the requirements of a project through developing a rational scope, generating viable schedules, identifying responsibilities, and managing prospects. Likewise, Kerzner (2001) defines project management success as completing an activity within time limits and budget with the achievement of the particular performance levels and the client’s satisfaction. Morris (2003) criticizes the aforementioned definitions because they emphasize on the execution tools and processes. He suggests that the definition of project management should be extended to include the significance of an expanded business context and strategy in addition to the people’s leadership within the project.

It has been argued that programs usually integrate several projects and fill the gap between their delivery and organizational strategy (Lycett, Rassau, & Danson, 2004; Project Management Institute (PMI), 2008). Lately, this strategy has been attracting a great attention especially with the development of new program standards by the Project Management Institute (PMI, 2008). Therefore, it is essential to apply appropriate approaches to analyze the performance of programs and consequently enhance learning and decision making process. This study focuses on the outcome of a program and its effectiveness within its context. The study is mainly concerned with stakeholders’ long term satisfaction to be included in the outcomes evaluation method. Therefore, MORE has been selected as the appropriate evaluation framework that would help the institute meet its own and stakeholders’ vision, mission and strategic goals.

The Role of Project Manager

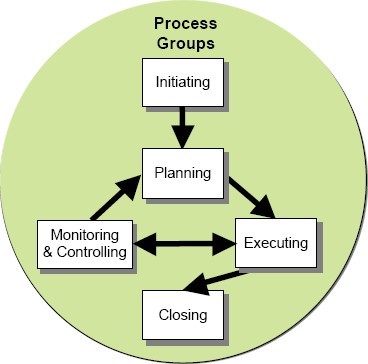

The traditional approach defines the five main phases of project management that apply to the majority of projects including the subject matter of this research. The five steps are: initiation planning and design, execution and construction monitoring and controlling (Kerzner, 2003).

Figure 1: Project Management Stages: Borrowed from: Project Management Guide

A proper model of general project management methodology that applies to the project management of educational institutes is provided by Burton and Michael (1999). They list the key stages of a well managed and well implemented project. According to them, accurate planning is the first step. It includes planning activities and tasks, time frames and tasks’ schedules, financial issues, human resources, project goals, and project production and results. They also emphasize on the right selection of project coordinator and other personnel with effective allocation of roles and responsibilities. The following step is matching activities to the time frame and the human resources. The fourth step is the monitoring and controlling followed by generating detailed documentation when the project is completed, (Burton and Michael 1999). Similarly; Bienzle H. (2001) divides successful project management into five stages with an emphasis on the importance of reporting, monitoring and evaluating processes for the success of a project. He states that the reporting process reveals how the project is going on while monitoring process facilitates the review of activities to ensure the progress is maintained towards the main goals. According to Bienzle H. (2001), the constant evaluation of activities helps is making any required adjustments in order to effectively achieve the objectives of the projects.

Now concerning monitoring and control, Newell (2005) writes that the process group devoted to the monitoring and control phase consists of whatsoever processes are necessary to exercise control over the execution phase of the project (p. 16). These functions include the abilities necessary to monitor the project, looking over it to establish the true results it is yielding, and the character thereof (p. 16). Aberrations, inconsistencies, and deviations from the requisite outcomes are made note of, and rendered subject to the overarching plan by means of the necessary adjustments of the control phase (p. 16).

Monitoring and control are, of a certainty, necessary and foundational to managing risks (Newell, 2005, p. 190). After all, they are the means by which risks may be detected, requisite solutions identified, and then the course of the project corrected accordingly (p. 190). Towards this end, a seminal part of any sound control phase must needs include a contingency plan, a plan that has been developed as a backup in case of a strategic risk to the overall plan (p. 190). The development of appropriate contingency plans is of great importance indeed; nonetheless, many is the occasion upon which an organization finds itself in need of course correction to preclude or address a risk, but has no contingency plan in place (p. 190).

Under such circumstances, the organization must needs to implement an ad hoc workaround, and simply manage the risk that way (Newell, 2005, p. 190). Such improvised solutions are often not so elegant and efficacious as contingency plans; nonetheless, quite often they are foundational to an ad hoc effort during the control phase, inasmuch as they may be the only way to ensure quality and a right, meet, and proper outcome for the project overall (p. 190). It is also important, by way of mitigating and managing risks, that assessments, reviews, and audits be conducted of the project in order to ascertain potential risks and deal with them efficaciously, lest they proliferate and grow in numbers and in magnitude, and become the more difficult to deal with (p. 190). Finally, documentation of identified risks and solutions implemented is of considerable importance, inasmuch as it can serve as a source of information to guide future responses to risks (p. 190).

One important dimension of control identified in the literature is control accounts, used to track financials (Taylor, 2007, pp. 142-143). While a small project may easily be monitored and controlled with a single budget, a large and complex project may demand the use of control accounts (p. 142). A large and complex project will have many different tasks, and it is often quite important to keep track of each task and every process, in order to efficaciously ascertain where the funding is really going, and how each segment of the whole is performing (p. 143). In order to facilitate such documentation, control accounts may be created, by breaking down the project into a number of smaller constituent elements, each of which may then be monitored with its own budget—a control account (p. 143). This is indeed a very important example of the use of controls, since deviations from the norm may efficaciously and readily be caught by using control accounts, whereas it would be much harder to track a problem or discrepancy if a single large budget was used (p. 143).