Everglades Costs, Research Paper Example

Development of the land in the Florida Everglades was not economically sound.

Introduction

The Florida Everglades is a troubled ecosystem; originally it was a free-flowing river of grass running from the Kissimmee lakes out to the Florida Bay that supported diverse populations of native birds and land animals. Land use changes over the past century have permanently altered the ecological regimes due to agriculture, urbanization, and the engineered diversion of surface waterways. The federal government and State of Florida are attempting to undo the environmental damage wrought by one hundred years of land change that have reduced the Everglades ecosystem to approximately 50 percent of its original extent (R. Walker, 2001).

Figure 1 – Everglades Area Change over Time (www.msnbc.com)

The first moves away from the natural environment towards the land use changes, began with the US Congress passing the “Swamp and Overflowed Lands Act of 1850”, which transferred Florida’s swamp and overflowed lands to State ownership for possible sale and usage of the land. Unfortunately, at the time there was no understanding about the integral natural ecosystem and the land was considered to be useless marshland. By 1927, over 665 miles of drainage canals, 47 levees, and 16 locks and dams had been built to divert the natural flow. This partial drainage of the Everglades opened the area to farming. The first commercial crops farmed in the Everglades were sugar cane, tomatoes, beans, peas, peppers, and potatoes.

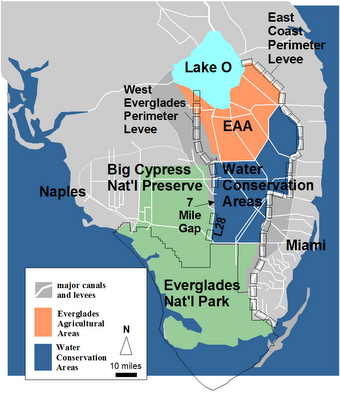

Figure 2 – General Everglades Land Use (www.gohydrology.org)

The US Army Corps of Engineers (USACOE) and the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) are responsible for organizing and developing the water management system. These two groups constructed the most elaborate and effective water management system in the world; unfortunately this project has had extremely negative effects on the Everglades and South Florida ecosystem.

From 1996 to 1999, teams of agencies and organizations were involved in an elaborate planning process to restore the ecosystem and meet South Florida’s water needs for the next 50 years. This plan is the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) and its purpose is to restore and preserve South Florida’s natural ecosystem while enhancing water supplies and maintaining flood control, the plan is expected to take roughly 30 years to implement.

The “Water Resources Development Act” (WRDA) signed into law in 2000 by then president Bill Clinton, approved of CERP as a framework and guide to everglades restoration. The law would provide $7.8 Billion to projects to use reservoirs, marshes, and hundreds of wells to collect, clean and deliver rainwater to the everglades, where some species are being led to extinction due to lack of freshwater.

As a part of the necessary Everglades restoration associated with the WRDA law, the Florida government has been in the process of attempting to purchase some of the land back. In June 2008, Governor Charlie Crist announced a $1.75 Billion plan to buy 187,000 acres of U.S. Sugar land. This deal would have put the State back in control of almost half of the over 400,000 acres of land owned by U.S. Sugar. Unfortunately by May 2009, the land purchase deal had been significantly downsized to only 73,000 acres for $536 Million. Progress on getting the deal signed has been slow if not at all, and the project was again downsized in June 2010, due in part to the recession, to only 27,000 acres for $197 Million.

Human development and progress over the past century have placed growing amounts of pressure on the Florida Everglades Ecosystem, this continual increase of stresses must be eliminated and remediated because the long term environmental costs far outweigh any short term financial gains. The focus of this paper is to prove that the development of land in the Everglades is not worth all of the cumulative restoration costs, which will be achieved through an analysis of the changing values of the land bought and sold and the agricultural and the water infrastructure systems costs from the 1920s to date.

Development Costs

Out of the $7.8 billion restoration plan which Congress approved for the Everglades ecosystem, the initial set of projects were seen to cost around $1.4 billion. Out of all these combined efforts, an investment seen by the state is bordering approximately $3.6 billion in state funds, and $2.3 billion in federal funds. These are seen being funded by not only by the state and the federal government, but also various stakeholders.

The Indian River Lagoon-South wetlands were seen to cost $1.2 billion in development, and the Picayune Strand ecosystem seen at $363 million. Congress had approved and authorized $700 million in federal shares for the initial projects which was a framework by the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP)

Restoration Costs

Table 1. DOI Everglades Appropriations, FY 2004-FY2005 ($ In Thousands)

| Agencies Requesting Funding for Everglades Restoration | FY 2004

Enacted |

FY2005

Enacted |

FY2006

Request |

| National Park Service | 44,329 | 45,116 | 67,702 |

| Fish and Wildlife Service | 16,342 | 12,075 | 12,531 |

| U.S. Geological Survey | 7,847 | 7,738 | 7,888 |

| Bureau of Indian Affairs | 539 | 536 | 388 |

| CERP Funding | [8,772] | [8,517] | [8,596] |

| Total Appropriations | 69,057 | 65,465 | 83,509 |

Table 1. Corps Everglades Appropriations, FY 2004-FY2005 ($ In Thousands)

| Activities for Everglades Restoration | FY2004

Enacted |

FY2005

Enacted |

FY2006

Request |

| Central and South Florida Project | 105,000 | 69,400 | [14,213] |

| Everglades South Florida Restoration | 12,800 | 25,792 | 137,000 |

| Kissimmee River Restoration | 17,700 | 17,856 | n/a |

| Florida Keys Water Quality Improvement | 0 | 2,232 | 0 |

| CERP funding | [39,063] | [67,000] | [68,000] |

| Total | 137,500 | 115,280 | 137,000 |

Restoration Benefits

Our goal is to place an economic valuation on the Everglades restoration. In order to classify the huge array of potential products and services flowing out of the Everglades, we envision this vast natural cauldron as a firm, where each product line has revenues and cost. In almost every case, the buyers place a higher value on the product than the purchase price. The Everglades system is like that, except that the buyers do not directly pay for the products they consume. Instead, consumption is enjoyed in large measure without any compensation to the owner or producer, because there is no well-defined owner and nature is the producer.

We approach this cost-benefit analysis as if Everglades were a multi-product firm, and we divide the values that consumers place on its products and services. In this scenario, Everglades restoration is akin to a business opportunity, and the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) is a detailed business plan. One of our tasks in this report is to produce a set of financial statements to complement and complete the plan. As with all projections formed we have made assumptions about the future. Accordingly, in the analysis below are our estimates at the lower end of the range and they follow best practices in economic methodology.

The multi-product firm, the Everglades, is broken into six distinct divisions. These are:

- Groundwater purification and aquifer recharge

- Real estate

- Park visitation

- Open space

- Fishing

Wildlife habitat and hunting

First service produced by the Everglades, the groundwater purification and aquifer recharge, will be restore sheet flow as planned in CERP. This will provide additional fresh surface water and groundwater. Additionally, the water available for municipal and private use will be less saline, requiring less infrastructure processing, as groundwater extracted for use by South Floridians will be less saline and require less treatment and electricity to become usable and potable. Because of the cost to desalinate water, one service that the restored Everglades would provide is reducing the cost of desalinating increasingly brackish groundwater. In order to assay this revenue stream, it is assumed that the restoration will return South Florida groundwater and surface water to its 1970 levels of salinity. From this assumption we can project how much money the people of South Florida will not have to spend desalinating groundwater as restoration unfolds.

For the second service produced, real estate, we can anticipate that the restored Everglades will improve the quality of surface water in 16 counties of South Florida Management District. It is important to note that water plays a role in the determination of residential real estate values. For example, lakeside or seaside properties sell at a premium to properties located away from bodies of water. As well as a home on a clear stream trades at a premium to a similar home on a polluted stream. Throughout years economists have developed techniques to quantify the incremental value of environmental attributes. This method estimates the price people are willing to pay for individual product characteristics and environmental goods, such as air and water quality. Studies consistently show that the water quality effect is positive; that is, property located on or around high quality water is more valuable than property located on or around lower quality water.

The park visitation, the third service produced, is that the Everglades restoration would increase the quality of leisure activities as well as the number of resident and non-resident visitors to the Everglades. This increase in recreational and tourist activity translates to an economic value. This economic value was measures using the travel-cost method where the basic premise is that expenses people incur while traveling to a recreation site or tourist destination represent the price of admission in the economic sense of opportunity cost. This outlay of expenditures reflects the traveler‘s willingness-to-pay, that is, the value that a recreationist or tourist places on accessing a particular site.

The open space is an important feature that is going to enhance the recreational opportunities and aesthetic benefits to the residents of South Florida. The CERP will produce approximately 157,555 acres of preserved open space, which will be accessible to the public and or developed as Florida’s population grows. This estimate was evaluated using the multi-stage process with data from the Public Lands to estimate type-specific and county-specific willingness-to-pay values per acre of preserved open space. The open space and conservation projects were grouped into three types: local open-space bond initiatives, state-wide conservation projects and federally funded wetland preservation projects. The county-specific willingness-to-pay values depend on numerous geographic and demographic variables, such as population density and proximity to population centers.

The fifth service produced by the Everglades restoration is the fishing business. This service is divided into two categories, commercial and residential, to distinguish the changes in fishing associated with restoration. For the commercial catch the data was divided by species from 1989 to 2008. It was assumed that restoration will enhance commercial fish catch, owing to increased sheet flow. The estimative change is a comparison between the current levels to peak levels in the late 1980s. Yet for the recreational fishing the data was used based on the Largemouth bass, the most common freshwater fish targeted in the Everglades region. For both components in the fishing the division it assumed that restoration would restore 75 percent of total fish population.

While fishing is a major recreational activity in Florida, hunting and wildlife viewing are popular pastimes as well. There are two important groups in the Everglades: deer and waterfowl (primarily ducks). Restoration stands to impact of hunting, it turns out both positively and negatively. Deer have moved into and flourished in the drained wetlands of the Everglades, and ducks have been driven out. Using the data from 17 statewide Wildlife Management Areas, the ratio of the economic value of hunting in the wildlife management areas was calculated. While the marginal impact of Everglades restoration on hunting expenditures might be negative, the expected change in wildlife-viewing expenditures is almost surely positive and far larger than the potentially negative impact on hunting expenditures.

The Table 1is presented the monetary value of each of these six categories in a conservative estimation, using the best available data and economic methods, the increase in economic value of a restored Everglades ecosystem.

Table 1 Cost Analysis of the Everglades Restoration

| Summary of Ecosystem Services Valuation of Everglades Restoration | ||||

| Service | NPV * | Best Estimate | ||

| 1 | Groundwater Purification | $ | 13,150,000,000 | |

| 2 | Real Estate | $ | 16,108,000,000 | |

| 3 | Park Visitation | $ | 1,311,588,000 | |

| 4 | Open Space | $ | 830,700,000 | |

| 5 | Fishing | $ | ||

| Commercial | $ | 524,100,000 | ||

| Recreational | $ | 2,037,000,000 | ||

| 6 | Wildlife Habitat and Hunting | $ | 12,539,900,000 | |

| TOTAL Value of Services | $ | 46,501,288,000 | ||

| Initial Investment | $ | 11,500,000,000 | ||

| Benefit-Cost Ratio | 4.04 | |||

| All calculations are based on discount rate of 2.1% | ||||

* NPV – Net Present Value Source: (Mather Economics, 2010)

References

CERP. (2010). “Everglades: A Brief History.” The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, <http://www.evergladesplan.org/about/learn_everglades.aspx> (Sept. 8, 2010)

Clement, Gail. Florida International University Library. (2010). “Reclaiming the Everglades: Everglades Timeline South Florida Boom and Bust.” Everglades Information Network and Digital Library, Florida International University Library. <http://everglades.fiu.edu/reclaim/timeline/timeline7.htm> (Sept. 8, 2010)

CERP. (2010). “Development of the Central & South Florida (CS&F) Project.” The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, <http://www.evergladesplan.org/about/restudy_csf_devel.aspx> (Sept. 8, 2010)

Natta, Don Van and Cave, Damien. (March 7, 2010) “Deal to Save Everglades May Help Sugar Firm.” The New York Times, <http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/08/us/08everglades.html> (Sept. 11, 2010)

SFWMD. (2010). “The Living Everglades.” South Florida Water Management District, <http://glades.sfwmd.gov/empact/home/02_everglades/08_faq.shtml> (Sept. 11, 2010)

Stapleton, Christine. (August 12, 2010). “$197 Million U.S. Sugar Land Deal for Everglades Cleanup Still Faces Challenges.” The Palm Beach Post, <http://www.palmbeachpost.com/news/state/197197-million-u-s-sugar-land-deal-for-855637.html> (Sept. 14, 2010)

Grunwald, Michael. (Jun. 24, 2008). “Booting US Sugar from Everglades.” Time Magazine, <http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1817390,00.html> (Sept. 14, 2010)

Everglades Foundation. (2006-2010). “U.S. Sugar Corp. Land Transaction.” Everglades Foundation, <http://www.evergladesfoundation.org/pages/us-sugar> (Sept. 14, 2010)

Walker, R. (2001). Urban sprawl and natural areas encroachment: linking land cover change and 19 economic developments in the Florida Everglades.

Cave, D. (2010, March 19). Renewed Support for an Everglades Land Deal, but Cost Is Still in Question. New York Times.

Mather Economics. (2010). Measuring the Economic Benefits of America’s Everglades Restoration. Palmetto Bay, Florida: The Everglades Foundation.

Milon, W. J. (Summer 2010). Who Wants To Pay For Everglades Restoration? The Magazine of Food(Farm and Resource ).

Natta, D. V., & Damien, C. (2010, March 7). Deal to Save Everglades May Help Sugar Firm. New York Times.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee