Le Corbusier and the Ville Radieuse, Research Paper Example

Introduction

The beginning of the 20th century was marked by innovations and progress in many spheres of the human activity – art, construction, design, industry, planning etc. The century gave realms of talented and risk-taking reformers who dared to voice their revolutionary ideas and spurred the global progress in many terms. The area of construction and architecture could not help being concerned by the path of progress and modernism as well. The urban planning techniques, city designs and innovative planning strategies overwhelmed the society both before and after two world wars.

One of the daring innovators known around the world is Le Corbusier (his true name was Charles Edonard Jeanneret) who became the pioneer in the urban planning and offered numerous solutions for the modern technological metropolises in the framework of the newly established European Modernism.[1] Le Corbusier became a famous architect because of his brave, ultra-modern and at times phantasmagoric ideas about urban planning, and manifested himself as a modernist in architecture and design. He is referred to as a heroic innovator; though many of his proposals did not find their support and financing, many of his ideas of resource availability and utilization of public space to optimize the social access to the utilities are applied in architecture and design nowadays as well.

Le Corbusier was an influential figure in terms of establishing a new concept of a modernist city in the 1920s. The traditional image of a city at the beginning of the 20th century encompassed both the physical phenomenon and the cultural, social object.[2] All architects of that time worked on the ways to reduce spatial limitations, and Le Corbusier was one of the pioneers in the field by proposing the Le Ville Radieuse project with innovative ground-building relationships. The traditional vision of modern urban cities was the one of chaotic, high-density metropolises, so the outbreak of the modernist tradition in urban planning, the representative of which Le Corbusier actually was, offered new solutions to the emerging urban problems of the early 20th century[3]

Le Corbusier is famous for many of his architectural works, including the Ville Contemporaine and Plan Voisin produced at the beginning of the 1920s – they reflected the architect’s utopian vision of the modernist city and included many deriving points for the development of harmonious urban design in the modernist trend.[4] However, one of Le Corbusier’s most remarkable works still remains the subject of discussion and dispute – Le Ville Radieuse produced by the architect as a plan for a new, Radiant City, sought to solve the main problems of growing, industrialized cities, overpopulated and irregular districts with little access to commodities, leisure activities etc.

The plan was never realized, but its elements are still the subject of intense debates for both spectators, specialists in design and construction, as well as artists. The functionalist approach utilized in Le Ville Radieuse was called to embody the progressive ideas of the functional harmony, to promote social equality and access to basic needs. The ethics contained in the geometrical forms of Le Ville Radieuse leaves much space for modern urban planning, but it should still be researched in the whole complicity of the political, historical, artistic and individual implications that shaped Le Corbusier’s philosophy and creative activity.

Description of the Project

Le Ville Radieuse was the idea of Le Corbusier of how to house three million residents in the center of Paris (which was six times more than the central Paris could actually house); hence, the project is often called “The Contemporary City for Three Million Inhabitants”. Le Corbusier offered to demolish a part of the center of Paris to build Le Ville Radieuse, but his idea left government officials indifferent. Le Ville Radieuse was a natural product of Le Corbusier’s philosophy of modernism in urban planning that introduced a rational city with strict separation of functions; it was an alternative to the chaotic, kaleidoscopic designs of that time and represented an entirely distinct vision of urban design.[5] Le Corbusier was actually a part of the architectural group who contradicted the traditional urban planning models of the 1920s and made their own urban planning against the city. Thus, the common trends of mixing the functions within a metropolis, merging the city with suburbs etc. were clearly denied in Le Ville Radieuse, offering the highly authoritative, structural, functionalist city that emphasized the hierarchical relationship between city and periphery, which can be seen from the general structure of Le Ville Radieuse.

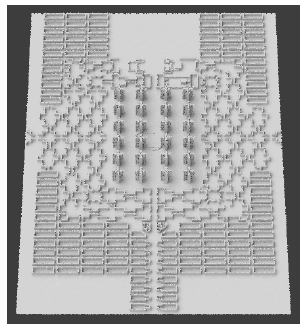

As one can see from Figure 1, the design of Le Ville Radieuse is mainly symmetrical in its center representing the transportation core (public transport). There is an access to subway at the lower deck of the underground station, and trains at the upper deck thereof, in the very center terminus. Air-uses and air-taxes are also available at that terminus, being located at the ground level of the transportation core. The central part of Le Ville Radieuse is occupied by twenty-four skyscrapers that are called to locate the business center of Le Ville Radieuse, and serve as hotels. They are cruci-formed, 190m x 190m, with height of over 200 m.[6] Here once can see the clear distinction between the city, periphery and countryside popular for the modern urban design of the 1920s.[7]

Figure 1. The General Design of Le Ville Radieuse

Source: from Montavon et al. (2006), p. 2

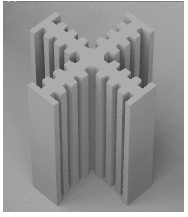

These skyscrapers were intended to house 500,000-800,000 people, with the skyscrapers becoming the civic center and location for the majority of leading firms. Skyscrapers were one of the most typical elements of urban design of the beginning of the 20th century, but Le Corbusier took an alternative viewpoint at them as well, seeing them as the powerful tool to solve the high-density problem of urbanism.[8] However, the design of skyscrapers that may be seen on Figure 2 is still considered controversial.

Figure 2. The Design of Skyscrapers in Le Ville Radieuse

Source: from Montavon et al. (2006), p. 2

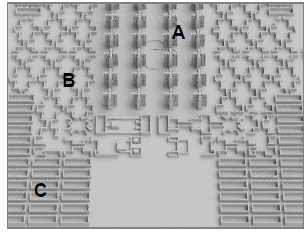

The residential districts were intended to be built around those skyscrapers, and were to provide housing for people working in the business center. That would decrease the amount of time to get to and from work, and would considerably unload the traffic in Le Ville Radieuse. The specific type of housing for that purpose was called ‘apartment-villas’ because of each apartment having a hanging garden to make it a house on its own.[9] There were three types of residential blocks designed by Le Corbusier that can be seen on Figure 3.

Figure 3. Three Types of Residential Blocks in Le Ville Radieuse

Source: from Montavon et al. (2006), p. 3.

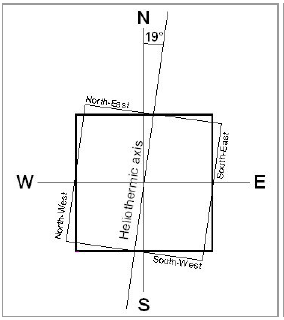

The main peculiarity of the whole Radiant City construction is that the districts (the business sector, the residential sector, the transportation core, the shopping area) are organized in the Cartesian way in which all elements have a functional role and contribute to the city’s functioning as a ‘living organism’, automatically and rationally. This idea stands out from the dominant urban planning design of the 20th century because of the traditional arrangement of cities as interwoven, merged hubs of all functions, tending to bridge the suburbs with city centers. Le Corbusier’s project is obviously an innovation in his inclination to rationality and structuring as an opposition to chaotic and kaleidoscopic cities of that time.[10] However, the major specificity of the project is that it introduces the heliothermic axis of city construction, which is the most desirable orientation of buildings according to the theory of exposition to daylight and air temperature.[11] The geographical illustration of the heliothermic axis principle may be seen on Figure 4.

Figure 4. The Heliothermic Axis Principle

Source: from Montavon et al. (2006), p. 5.

As described by Dluhosch and Svacha (1999), Le Ville Radieuse has a standardized residential element, and transportation is provided by the piloti construction system allowing a freer disposition of routing of pedestrian ways.[12] Vehicular streets are raised to the level of the first floor, and residential streets are located inside the blocks. Orientation is loose, but closed corners limit the access to sunlight for some apartments. The overall area of streets occupies only 9% of the whole Le Ville Radieuse, while the territory of open spaces is about 91%.[13] Inhabitants planned for the hectare of Le Ville Radieuse’s area are 1,000.

Analysis of Le Ville Radieuse

The project of Le Corbusier called Le Ville Radieuse is an indisputable illustration of the architect’s inclinations towards the functionalist approach in city planning that was rather popular in the 1920s as an opposition to chaotic urban structures. The project represents a high-density city that takes into consideration the human need to access day light and use the solar potential in full, which is the innovation in itself, since Le Corbusier was one of the first architects to disperse the city according to human needs.[14] The very design of skyscrapers was intended to provide as much access to the basic human needs such as sun and air, while the functional disposition of streets enlarged the area of greenery accessible by the whole community. In general, le Ville Radieuse was intended to solve four problems of modern metropolises:

- To provide efficient communication networks

- To ensure the enlarged, vast areas of greenery throughout the city

- To increase access to sun (by means of construction and location of buildings)

- To reduce the negative impact of the heavy urban traffic that grew to become an aching problem of large, overpopulated cities in the 1920s[15]

The functionalist approach was kept by Le Corbusier for several reasons that will be discussed further; however, one can see from the previous section how well the city planning design was organized to ensure the equal and easy access of the community to all commodities, to the large amount of greenery and gardens, as well as “open green spaces” provided by raising the level of streets responsible for traffic and pedestrian movement up to the first floor, leaving the ground not too overloaded by these conventional functions of streets.[16]

The full daylight access and the solution to the urban noise problem that were also considered the most desirable accomplishments of urban design were ensured in Le Ville Radieuse; Le Corbusier arranged the location of residential areas and business sectors in such a way that the interference or overlapping between them would be impossible, reducing the traffic in residential areas to minimum due to the rational, functional location of roads. The reason for successful rationality was that the area occupied by buildings was only 15% of Le Ville Radieuse, which provided enormous leisure and sports, natural and greenery facilities for the residents and ensured little loading for all sectors except the business one where skyscrapers were intended. These intentions seemed to be accomplishable to Le Corbusier because of the advancement in construction technology of 1920s, and the architect wanted to solve the problem of overpopulation by housing six times more residents in Le Ville Radieuse than the typical urban area of that square could accommodate.[17] This intention in Le Ville Radieuse illustrates Le Corbusier’s fascination with the image of a dispersed city organically merged with the high-density city, which fully corresponded to the social and economic needs of the 1920s.

The design of residential buildings also has many functionalist implications, as there were three types thereof designed by Le Corbusier for Le Ville Radieuse. They included housing ‘set-backs’, housing ‘cellular’ and ‘garden cities’, and the façade surface preferred by the architect had deeply serrated shapes instead of the plane surface conventionally used in construction design.[18] As Montavon et al. (2006, p. 3) have found out by means of the experiment they conducted with the simulation of Le Ville Radieuse, the idea of Le Corbusier would have indeed worked because these shapes provided veritable traps for daylight, and increased the solar energy access considerably. In addition, the researchers have found out that the heliothermic axis proposed by Le Corbusier (in his initial intention to implement Le Ville Radieuse project in the center of Paris) would also increase access to solar energy, especially in the winter periods, which proved the functionality of Le Corbusier’s proposal though not in full. [19]

It is surely doubtable whether the daylight access increase that constituted one of the main intentions of Le Corbusier was fully achieved by him in Le Ville Radieuse, as Montavon et al. (2006) note; the daylight viability observed in realistic Paris settings and the simulation of Le Ville Radieuse prove that the Radiant City, if built, would not be radiant at all.[20] However, the project’s construction planning would obviously provide a set of advantages for the urban area; the huge amount of usable floor area and open space it would provide represent the major contribution of Le Corbusier to solve the urban problems of over-population.

Interpretation of Le Ville Radieuse Project

The first impression one has when studying the Le Ville Radieuse projects is that it clearly embodies the notion of monumentality. As the Ghent Urban Studies Team has noted, the project enters into a specific relation with the past of the construction site, and history in general, being new and definitive at the same time, and standing outside history because of having no past experience, no history of previous construction etc.[21] The project looks like a brand new discovery that has never been implemented before, and it reflects weird relationships of the old design’s remnants and the new buildings. The result may never be called a mixture of old and new elements, though both are present; the expanded monumentality spreads on all elements of the design, giving them freshness, uniqueness and no chance for the dialogue.[22]

Another important interpretation of Le Ville Radieuse states that it reveals the doctrine of the new machine age. Indeed, as Bacon (2003) notes, the doctrine of functionalist approach to construction emerged in the USA in the second era of machine civilization, after the US market crash.[23] The technologically advanced society started to employ rationalized, standardized methods of organization, which could not help being reflected in the urban design as well. However, the priority was given to organic structures and processes as well, which found its reflection in Le Ville Radieuse – despite the heavy emphasis on rationalization and mechanization, the architect still gave priority to the communal comfort, rational distribution of space and access to greenery, leisure facilities and open space, which was not exactly what the mechanization age took care about.

The shift in Le Corbusier’s architectural philosophy is remarkable, and it is best of all seen on the example of his ideas reflected in Le Ville Contemporaine first, and the in his Plan Voisin. Le Ville Radieuse was a shift towards a new stage in Le Corbusier’s design principles, and Bacon (2003) sees the difference in the reflection of the collective principles and progressive ideals of the Congres Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM).[24] The Congress called to pursue the ideal of harmony in architecture and urban design, to abandon the sterile practices of the theoretical design education and to strive to the economic and sociological plane implementation. In fact, CIAM became the host of ideas of standardization, increased productivity, reduced costs, and enhanced labor, which found the immediate realization in Le Ville Radieuse.[25]

An essential contribution of Le Ville Radieuse was that Le Corbusier pursued his formalist philosophy in urban design, but made the new project more regionally dispersed. In addition, Le Ville Radieuse responded to the social needs of that time, and reflected the new organic concerns of the era of mechanization, thus becoming a highly actual and topical project, especially in the USA. Ethical Implications of geometrical forms that Le Corbusier implied helped solve the major construction problems; as it was conventionally seen, streets had to follow the construction models. However, Le Corbusier claimed that the streets should not be defined by the location of buildings, so positioning them on the pilotis was the grand solution of the traffic issue first, and allowed the unlimited imagination of the architect to flow without considerations of street location.[26] This element responded to the human and optical factors in design, which Le Corbusier called “the sense of movement in space”, the “human scale impressions” or the “optical reactions”.[27]

One more typical feature of the 1920s and 1930s is seen in Le Ville Radieuse: it reflects the capitalist features of urban separation from agriculture, as it has already been mentioned. The typical modernist metropolis as seen by Le Corbusier is isolated from the country, which is evident from the location of the agricultural sector outside Le Ville Radieuse in the project.[28] This feature reveals the transformation of a traditional town into the modern urban metropolis dominating all trends in architecture of that period, though it was not always observed in urban design, especially in the post-war period when unification of suburbs and cities, mainly by means of enhanced transportation, was conducted.

The inclination of Le Corbusier to strong power and authority is also evident in the Le Ville Radieuse project. Though Le Corbusier never regarded himself as a politician, he always spoke freely about his inclinations towards strong authoritarian politics.[29] Le Corbusier viewed power and the nation in the lens of family relationships, where the government were the parents who knew better what their children needed. Hence, the book Le Ville Radieuse, as well as the construction project, was filled with enthusiasm towards authority, strong leadership, great men, and calls for the strong political authority needed for the implementation of Le Ville Radieuse in reality. His criticism directed at the American cities and urban design also derived from the ideas of authority: he stated that American cities were “cities of despair”, “locked in stasis”, “paralyzed by indecision” because of lack of strong leadership in the country.[30]

The significant contribution of Le Corbusier to the theory of modernist urban design may be also seen in his reformulation of the theory that existed in the 1930s, and introduction of the concept of the architect’s social responsibility in construction. As Bacon (2003) notes, Le Corbusier considered it essential to make urban design respond to human needs first, which he called the essential joys, or basic pleasures.[31] Le Corbusier thought that only skyscrapers and the application of advanced technology could not meet the human needs, so the extended access to the basic needs such as sun, air, open space, and leisure activities became the items of utmost priority for him. However, there is still much contradiction in the social class attitudes and intentions voiced by Le Corbusier in the Le Ville Radieuse project; in the early times of project development, the architect often compared it to the luxury liner, being isolated in the ocean, but having everything people needed in its decks.[32] Thus, Le Corbusier included the elitist element in the comparison, that is, Le Ville Radieuse being the dwelling for the chosen, by which he tried to attract sponsors and contractors to implement the project in reality. However, later on Le Corbusier insisted on le Ville Radieuse being the single class project that was called to solve the social dilemma of the 1920s, when the stress and contradiction between the working class and the upper class intensified and were fueled by the success of the October Revolution in Russia.

Conclusion

Le Corbusier is viewed as an outstanding personality in the history of modernist design because of his daring ideas and innovation he managed to bring into the world of architecture and design. Alongside with the traditional vision of urban design as a kaleidoscopic, chaotic, high-density city, Le Corbusier was more interested in the organic unification of social needs for open space, and the need to house the growing population of metropolises. Though the idea of Le Ville Radieuse was never realized, Le Corbusier indisputably left a trace in the formation of major construction models, patterns and policies that included rationality, functionalism and strict distribution of functions in the city so untypical for the 1920s and 1930s. Le Ville Radieuse is still viewed as a utopia of urban planning, but at the same time it is regarded as the universal lodging where urban functions were mixed and not bureaucratically, functionally categorized. The public space was packed by people who had equal access to all commodities presupposed by the design of Le Ville Radieuse, and the planning scheme allowed buildings, and houses in particular, to become the part of context and history.[33]

Le Corbusier’s doctrine seemed to undermine the very essence of urban planning, and his linear city revealed much contradiction with the vertical axis of symmetry used in the construction and urban design; however, the ideas voiced in Le Ville Radieuse, reflected the gist of the epoch in which Le Corbusier lived and worked. The political dogmas of authoritarianism, the urban growth and dilemma of overpopulation in metropolises, the very transformation of the image of a traditional European city – all this could not help contributing to the richness of Le Corbusier’s ideas and projects. The image of a communal city with access to all essential commodities, with vast green areas, elevated streets and structured functional areas was surely the innovation hard to implement in the 1930s. This may be the reason for Le Ville Radieuse to remain a theoretical utopia and guide for architects of modernity. However, Le Corbusier’s intentions to ruin the spatial limitations within the city and the symbolic meaning he attributed to streets and buildings located on pilotis marked the distinct field of urban planning and design highly non-traditional for the period of technology, consumption, demographic explosion and urbanization.

Le Ville Radieuse is a significant stage in the creative activity of Le Corbusier for several reasons; first of all, it marks the transition of the architect’s creative spirit to the lens of social responsibility, functional fusion of sectors and rationality felt in every part of the disposition. Le Corbusier marked the beginning of a new trend in the functionalist modernism by generating Le Ville Radieuse and propagating its postulates. Secondly, the project itself is a very interesting example of urban planning technologies utilized in the 1920s, 1930s and later on; it reveals the political, economic and ideological implications of technological advancement, technical civilization era emergence, the dominance of mechanics over the lives of nations, neglect towards nature under the pressure of technocratic requirements of governments etc. The need for organic models and structures in design, the social direction taken by Le Corbusier in the formation of Le Ville Radieuse project, marks a heterogeneous interweaving of political, artistic, individual and social motives that found their harmonious reflection in the plan called to help people live better, but never realized and tested in life.

Bibliography

Bacon, Mardges, Le Corbusier in America: Travels in the Land of the Timid, New York: MIT Press, 2003.

Dluhosch, Eric, and Rostislav Svacha, Karel Teige, 1900-1951: l’enfant terrible of the Czech modernist avant-garde, New York: MIT Press, 1999.

Ghent Urban Studies Team, The urban condition: space, community, and self in the contemporary metropolis, Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 1999.

Marylene Montavon, Koen Steemers, Cheng, Vicky, and Raphael Compagnon, “‘La Ville Radieuse’ by Le Corbusier once again a case study”, The 23rd Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

Von Moos, Stanislaus, Le Corbusier: elements of a synthesis, Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2009.

[1] Von Moos, Stanislaus. Le Corbusier: elements of a synthesis (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2009), p. 43.

[2] Ghent Urban Studies Team, The urban condition: space, community, and self in the contemporary metropolis (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 1999), p. 15.

[3] Ghent Urban Studies Team, p. 17.

[4] Bacon, Mardges. Le Corbusier in America: Travels in the Land of the Timid (New York: MIT Press, 2003), p. 63.

[5] Ghent Urban Studies Team, p. 17.

[6] Marylene Montavon, Koen Steemers, Cheng, Vicky, and Raphael Compagnon, “‘La Ville Radieuse’ by Le Corbusier once again a case study”, The 23rd Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Geneva, Switzerland, 2006, p. 1.

[7] Ghent Urban Studies Team, p. 27.

[8] Ghent Urban Studies Team, p. 18.

[9] Montavon et al., p. 2.

[10] Ghent Urban Studies Team, p. 40.

[11] Montavon, p. 5.

[12] Dluhosch, Eric, and Rostislav Svacha, Karel Teige, 1900-1951: l’enfant terrible of the Czech modernist avant-garde (New York: MIT Press, 1999), p. 173.

[13] Dluhosch and Svacha, p. 173.

[14] Montavon et al., p. 1.

[15] Montavon et al., p. 2.

[16] Montavon et al., p. 2.

[17] Montavon et al., p. 1.

[18] Montavon et al., p. 3.

[19] Montavon et al., p. 4.

[20] Montavon et al., p. 6.

[21] Ghent Urban Studies Team, p. 414.

[22] Ghent Urban Studies Team, p. 414.

[23] Bacon, p. 63.

[24] Bacon, p. 63.

[25] Bacon, p. 63.

[26] Bacon, p. 81.

[27] Bacon, p. 81.

[28] Dluhosch and Svacha, p. 166.

[29] Von Moos, p. 219.

[30] Bacon, p. 67.

[31] Bacon, p. 108.

[32] Von Moos, p. 160.

[33] Von Moos, p. 222.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee