Medical Tourism Development in Malaysia, Dissertation – Literature Example

Abstract

This work examines the growth of medical tourism throughout the world and specifically in the country of Malaysia. Findings show that Malaysia has a highly organized medical tourism industry that receives the full support of the government.

Introduction

Medical tourism is experiencing rapid growth throughout the entire world as countries seek to enter the lucrative medical tourism industry. Medical tourism involves the seeking of medical treatment and services in the same way that individuals choose their vacation spots or other tourism locations. It is reported in one work that a “…fairly new phenomenon may be observed, which is that of people from developed countries travelling to developing countries to seek medical care. Many reasons have been suggested for this, including the long waiting lists in the healthcare services of some developed countries, and the high costs of care in these countries coupled with a lack of medical insurance, or under-insurance (Garcia-Altes 2005 in: Leng, 2010)

The commoditization of health care is stated in the work of 2010) to be “…is inextricably linked to the expansion of markets in healthcare, and to the rise of neo-liberal economics, which emphasizes the desirability of consumer choice as one reason for the promotion of markets. As healthcare is commodified, patients are recast as consumers.” (2010) Leng goes on to that this “…follows from the logic that commodities are produced for consumption. Meanwhile, the changeover from patient to consumer is supported by the increasing availability of information on clinical conditions on the one hand, and by more standards being imposed on professionals (for example, clinical practice guidelines, best practice guidelines) on the other. Among the consequences of healthcare commoditization therefore is the change in the nature of the relationship between patient and doctor. As consumers and providers respectively, the relationship will be primarily regulated by the rules of the market, in which profit-making is legitimately foregrounded.” (Leng, 2010)

Medical Tourism

UNESCAP, EGM (2007) reports that as the healthcare companies “…integrate across national borders, they create an international market for healthcare services. Even if medical tourism was a lifeline for these healthcare corporations in the first place, the synergy created by corporations expanding and integrating across national borders in turn encourages the further expansion of the medical tourism market.” UNESCAP, EGM (2007) states that one of the primary reasons for healthcare corporation acquisition of facilities in different countries is “… so that they can use these facilities to refer and cross-refer patients: a hospital in Indonesia or Vietnam may refer patients to another hospital in Singapore, where both hospitals are owned by the same corporate entity. At the basic level, however, the expansion of medical tourism hinges on the cultivation of healthcare customers; turning patients or potential patients into consumers of healthcare, who willingly travel abroad for their consumption. For this to happen, healthcare services has to be commodified so as to facilitate the process of consumption; so that it becomes easy and feasible to consume healthcare services even if one has to cross national borders in order to do so.” (UNESCAP, EGM, 2007)

The process of commoditization of healthcare is stated to be reflected in three specific features:

- Use of and emphasis on marketing;

- Increasing emphasis on quality; and

- Process of commoditization is the creation of customers and consumers. (UNESCAP, EGM, 2007)

Global Medical Tourism Development

Medical tourism is reported in the work of Bookman and Bookman (2007) entitled “Medical Tourism in Developing Countries” to be ”presently small in comparison to the overall service trade or the consumption of medical services worldwide or even the trade in tourism services” however, it cannot be dismissed as “temporary or insignificant” as medical tourism is the fastest growing segment of the tourist markets in Thailand, Malaysia and India.” (Bookman and Bookman, 2007)

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that medical tourism is a growing trend with enormous economic implications.” (Bookman and Bookman, 2007) It is reported that more than 130,000 foreign patients received treatment in Malaysia in 2004 and Malaysian hospitals report a 25% rise in foreign patients. (Bookman and Bookman, 2007, paraphrased) Thailand is reported to have 400,000 foreign medical tourists each year and India states that their foreign patients have risen by 30% each year. Jordan states expectations for approximately 100,000 medical tourists annually and Argentina states expectations that their number of medical tourists will rise by 50% annually. Finally, Costa Rica claims 150,000 medical tourists each year.

The reasons that people travel for medical care is due to the unavailability of such care locally or for reasons linked to savings in medical costs and expenses. Medical tourism has been enabled to the “liberalization of trade in services, the growing cooperation between private and public sectors and the easy global spread of information about products and services as well as the “successful splicing of the tourism and health sectors.” (Bookman and Bookman, 2007)

Bookman and Bookman report that health services is defined by GATS as “specialized services by doctors, nursing services, physiotherapeutic and paramedical services, hospitals services, ambulance services, residential health facilities services and services produced by medical and dental laboratories.” (Bookman and Bookman, 2007) In addition trade in health services include imports of professionals, technical training abroad, services for building and designing health facilities, and also domestic population going abroad to buy health care.” (Bookman and Bookman, 2007)

MacReady reports that medical tourism has become “a US$60 billion a year business and is growing by 20% a year.” (2007) Medical care is being sought in developing nations due to the differences in costs, wait times, and general “red tape”. (MacReady, 2007) MacReady reports that hospital administrators who are smart are “…actively courting patients who are willing and able to circumvent the shortcomings of their own health-care systems, opting instead to have their prostate surgeries or joint replacements at foreign hospitals that welcome them—and their pounds, dollars, and Euros—with open arms.” (2007)

Reported as well by MacReady is the fact that also fueling the growth in medical tourism is the factor of “vanity…when thrifty American baby boomers discovered they could save money, even including travel costs, by going to Thai or South American hospitals for some discreet cosmetic surgery. Foreign hospitals seem even more appealing now, as the cost of therapeutic procedures in the USA skyrockets, and the number of Americans without health insurance approaches 50 million.” (MacReady, 2007)

It is reported that investigation of a foreign hospital should include the following items:

- Domain: are the facilities and infrastructure well maintained and up-to-date?

- Doctors: are they credentialed and board-certified?

- Data: what kinds of statistics does the institution collect, and do they make them available to potential patients and certifying agencies?

- Death: are morbidity and mortality data available? How do they compare with the rates at home?

- Due diligence: who exactly are you dealing with? Can you visit the hospital, tour its facilities, and meet the staff? (MacReady, 2007)

MacReady states that all indications point to the market maintaining “standards of quality and accountability.” (2007) In addition that are various companies in Europe, North America and other places that accompany patients through the process including making plane reservations and arranging the necessary care and after-care. In addition, some agencies “will even arrange to let patients recuperate at a ‘luxury Asian resort’.” (MacReady, 2007) It is reported that aging populations in Europe, North America, and Japan result in hospitals in these regions seeing a small but steady loss of highly remunerative procedures as more and more people who have no inadequate health insurance go other places for their care. Predictions are that insurance companies will develop products specifically for the medical tourism market and emerging nations will build more privately financed corporate specialty hospitals to capitalize on their fairly low-cost labor forces. (MacReady, 2007, paraphrased)

Hopkins, et al (2010) states that medical tourism is “one manifestation of globalization” which is “driven by high health care costs, long waiting period, or lack of access to new therapies in developed countries”. Individual patients risks are stated to be offset by “credentialing and sophistication in some destinations although “lack of benefits to poorer citizens in developing countries offering medical tourism remains a generic equity issue.” (Hopkins, et al, 2010)

Medical Tourism in Malaysia

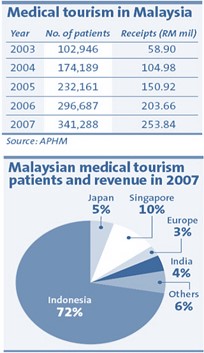

Medical tourism in Malaysia is experiencing rapid growth as Malaysia is not only a tourism destination but is a location known as well for its cultural, historical, and natural attractions. Medical tourism receipts in for Malaysia are reported to have “quadrupled to RM253.84mil.” (Ang, 2009) Reports show that patients from Indonesia comprised 72% of the foreign patients with 10% of patients coming from Singapore, 5% of patients from Japan and 3% of patients from Europe with 3% also from India. The favorite destinations for medical tourism in Malaysia are reported to be those of:

- Penang;

- Malacca; and

- Johor Baru. (Ang, 2009)

There are presently 35 private hospitals committed to promoting medical tourism in the country of Malaysia. Ang (2009) reports that the Association of Private Hospitals of Malaysia (APHM) board member and chairman of the committee on database and medical tourism, Datuk Dr K. Kulaveerasingam” states projections of a 15% increase as compared to 20-20% increases in medical tourism during 2009 with fewer foreigners expected to visit Malaysia for medical treatment due to economic slowdown. (Ang, 2009)

It is reported that the economic slowdown has resulted in some medical tourists postponing their treatments including such as knee and hip surgeries. (Ang, 2009, paraphrased) It is reported that the director of the Island Hospital Penang and Penang Health Association chairman Datuk Dr. Chan Kok Ewe states expectations for flat growth for medical tourism for the group this year due to the slowdown and relative market saturation, especially in traditional markets.” (Ang, 2009) The outlook is reported to be less than encouraging and it is stated that this slow period should be used to prepare for the next phase of growth requiring cultivation of new markets with a “structured strategy and guided investments.” (Ang, 2009)

It is stressed in this report that medical tourism requires development as a “nationally committed project, which consists of decent national budgets rather than what individual private hospitals can afford to spend.” (Ang, 2009) Chan states that most of medical tourists come from Indonesia and that Penang is selected due to it being located close as well as the “convenience of travel, and ease of cultural and language adaptation.” (Ang, 2009) Ang (2009) reports that gross receipts for members of the Penang Health Association “totaled RMI 156.53mil in 2007 and RM166.15mil in 2008.” Medical tourists are stated to comprise approximately 15 to 30% of the members’ patients. (Ang, 2009, paraphrased)

Malaysia is reported to be targeting new markets including those of Vietnam, the Middle East, the U.S., Canada, and Cambodia. (Ang, 2009, paraphrased) Ang reports that there is a stress on the importance of “branding for the country’s medical tourism industry to provide a better platform to market and promote the product.” (2009) Toward this end brochures are being pointed that will provide a “holistic view of Malaysian healthcare to appeal to medical tourists.” (Ang, 2009) The following table lists the number of patients and receipts in Malaysia for medical tourism for the years 2003 through 2007.

Figure 1

Malaysian Tourism 2003-2007

Source: (Ang, 2009)

It is reported that Abacus international states projections that the medical tourism in Asia will be worth approximately US$4bil by 2012. Ang reports that research show that the medical tourist’s expenditures are approximately double the amount per day of a normal tourist and specifically “US$362 as compared with US$144 per day.” (2009)

The work of Gupta (2009) entitled “Malaysia Medical Tourism Outlook 2012” states that medical tourism “has emerged as the fastest growing segment of the tourism industry despite the global economic downturn. High cost of treatments in developed countries, particularly in the USA and the UK, have been continually attracting patients from such regions towards alternative cost-effective destinations like Malaysia, India and other Asian countries. At present, medical tourism in Asia is in its infancy, but has an enormous potential for future growth and development.”

Gupta additionally states that according to the findings in the research report “Malaysia is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the ASEAN region. Despite the global economic slowdown, it received around 22 Million international tourists in 2008, an increase of around 5% over the previous year (2009). Singapore, Indonesia, and Thailand are important sources of visitors for the country.” (Gupta, 2009) In addition Malaysia is reported to have “…one of the most developed healthcare infrastructures in the region and is considered as the paradise for healthcare facilities and hospitals. Malaysia received around 75% of medical tourists from the ASEAN region, followed by Japan and Europe at 3% each, India at 2% and others at 17% in 2008.” (Gupta, 2009) Medical tourism in Malaysia is reported to have become a major segment of the tourism industry due to its medical excellence and high quality services in combination with medical specialists who are well trained. Malaysia had a network of private hospitals with offerings of “…comprehensive services in all-medical disciplines.” (Gupta, 2011)

Gupta reports that Malaysia’s “low cost advantage, booming tourist industry, and large inflow of patients from neighboring countries” will serve as drivers of growth and projections of revenues from medical tourism are stated at 23% for 2009-2012. (Gupta, 2009) Malaysia is reported to be very different from other such destinations in the areas of “cost, infrastructure, human resources, patient perceptions, competencies, and the level of government support.” (Gupta, 2009)

Frost and Sullivan (2010) report that Malaysia is “…fast becoming the destination of choice for healthcare tourists behind established medical tourism locations Singapore and Thailand. Many local private hospitals now offer a variety of medical packages and special arrangements for foreign patients.” People who are traveling to other countries for medical treatment is on the rise and driving factors are stated to include such as: (1) affordable cots; (2) better specialization; (3) quality of medical care; (4) short waiting periods; and (5) advanced technologies. (Frost and Sullivan, 2010 )

Frost and Sullivan additionally state that global medical tourism “…is a rising trend, and at an expected global revenue of RM244billion in 2010, Malaysia has a lot of growth potential to tap into the medical tourism market as well as target new markets.” (Frost and Sullivan, 2010) A growth rate of 15% for 2008 and 2009 is stated with the number of individuals visiting the country for the purposes of medical tourism having “more than quadrupled since 2003 to hit approximately 425,500 in 2009.” (Frost and Sullivan, 2010)

Malaysia is reported to target “…the cost-conscious, middle-range group and is particularly renowned for cardiovascular and orthopedic procedures, although Malaysia has patients for a variety of treatments including dental, aesthetics, optometry, obstetrics, gynecology and more.” (Frost and Sullivan, 2010) Frost and Sullivan report as well that a hospital and country “can typically attract international patients by market or by specialization.” (2010)

According to Leng (2010) the healthcare system in Malaysia is “a mixed public-private one”. Leng states that the number of doctors in Malaysia is “fairly balanced” with 54% of doctors being in the public sector and 46% of doctors in the private sector. The majority of private sector doctors are reported to be general practitioners. Leng additionally relates that the healthcare system was under the domination of a “public service ethos at the time the country “gained Independence from the British (in 1957) and thereafter. The rural health system was rapidly built up in the 1960s and 1970s, and is now constituted by an extensive network of clinics, which form the first point of contact in a referral system that goes through the district hospitals, and end at the various state and tertiary hospitals. Up until the 1970s, and even until the early 1980s, the healthcare system was practically a national health service, insofar as the vast majority of the population was rural and had to depend on the public health services, which were financed primarily from taxation with only nominal charges at the point of use.” (2010)

The 1997 Asian financial crisis resulted in Malaysia looking toward Medical tourism. A move that was full supported by the Malaysian government. In January 1998, the National Committee for the Promotion of Medical and Health Tourism was formed by the MOH with five subcommittees covering “various types of action considered necessary to attract foreign patients” and these included:

- one for identification of suitable source countries for prompting health tourism;

- one for drawing up tax incentives;

- one for fee packaging;

- one for accreditation guidelines; and

- one for advertising guidelines. (Leng, 2010)

Committee functions included:

- strategic plan formulation;

- promoting of partnership between government, healthcare facilities, travel organizations, and medical insurance groups;

- forging strategic alliances with overseas centers of excellence for mutual benefit. (Leng, 2010)

The External Trade Development Association (MATRADE) and Tourism Malaysia have carried out road shows and other marketing promotions. (Leng, 2010) Leng additionally reports that “….hotels and tourist agencies are linking up with medical centers to offer holiday packages that combine hotel accommodation together with health screening and medical check-ups. For example, Country Heights Health Tourism (CHHT), a private limited company, was intending to bring in 10,000 tourists (equivalent to an estimated RM 48 million14 worth of business) from Indonesia and Europe for preventive health screening, offering a battery of diagnostic tests including fluoroscopy and abdominal ultrasounds, within a five-star resort.” (2010)

It is also reported that a publicly-listed company, specifically ‘Resorts World’ “launched a health holiday package, tying up with HSC Medical Centre while the Palace of the Golden Horses Hotel in Kuala Lumpur built a RM 6 million medical centre within its premises, offering a battery of tests with results delivered within five hours. In the state of Penang, Beautiful Holidays, offers plastic surgery packages in conjunction with the Loh Guan Lye Centre, a 25-year old hospital.” (Leng, 2010)

It is reported that a “strong element in the Malaysian strategy is to capitalize on its image as a ‘Muslim country’, with easily available halal food and conveniences for practicing Muslims. The Muslim countries targeted include Middle East countries, Brunei, and Bangladesh. Gleneagles Intan Medical Centre, for example, formed a partnership with a Bangladeshi company (that did not initially have any interests in healthcare, but were engaged in furniture, automotive, home appliance and urban taxi services), whereby patients will meet up with appointed medical representatives in Bangladesh who will assess the type of treatment needed and give an estimate of costs before travelling to Malaysia.” (Leng, 2010)

Stated to be a common marketing strategy of hospitals is appointment of local agents and the example given is that Sunway Medical Center in Petaling Jaya “has an agent in Medan, Indonesia, who conducts talks for the public, and meets with doctors there, and arranges tourism packages that include airport transfers, accommodation for accompanying family members, shopping, sightseeing tours, etc.” (Leng, 2010) Another stated example is that of Mahkota Medical Centre in Melaka, which has a local representative in Indonesia to handle enquiries on a daily basis, while its marketing director and other officials travel fortnightly to Indonesian towns to carry out promotions among the public and doctors, as well as to maintain links with the authorities.” (Leng, 2010)

Medical Service Coordination International was launched in December 2003 and aggressively employs these strategies including targeting Muslim countries and agents being tied with these countries. Medical Service Coordination International acts as a “one-stop medical tourism agency among various parties locally and abroad. In Malaysia it collaborates with a panel of hospitals – the government-owned National Heart Institute, as well as Sunway Medical Centre, Gleneagles Intan Medical Centre, six hospitals in the Pantai group, and six hospitals in the Kumpulan Perubatan Johor (KPJ) Group, while in Indonesia, it has teamed up with 20 travel agents.” (Leng, 2010)

In an initiative with the Association of Private Hospitals Malaysia (APHM) the MOH, Ministry of Culture, Arts and Tourism and the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, the Medical Service Coordination International agency created a commercial on medical tourism, which was aired on satellite television stations and beamed to West Asia. The state and the tourism industry is Malaysia emphasizes quality and there have been 35 hospitals selected out of more than 220 for the purpose of promoting Medical Tourism in Malaysia. (Leng, 2010, paraphrased)

Leng states that each of these hospitals are listed as the Association of Private Hospitals Malaysia (APHM) website. Efforts for institutionalization of quality assurance programs include providing encouragement for private hospitals to seek and acquire governmental accreditation and quality (MS ISO 9000) certification. (Leng, 2009, paraphrased) Another quality assurance step is affiliation with healthcare center with high standing including the MAYO clinics, John Hoskins University Medical Center and others. Tax care incentives are used by the Malaysian government for encouraging healthcare industry development. Tax incentives are given for construction of hospitals, use of medical equipment, pre-employment training, promotion of services, and use of information technology. (Leng, 2010)

Additional incentives have been promoted by the national committee on health tourism to include tax exemptions from foreign patient revenue in excess of 5% of the total hospital’s revenue, “double deduction for money spent on accreditation and reinvestment allowance in relation to accreditation requirements.” (Leng, 2010) As well, Leng (2010) report that the “…conventionally stringent prohibitions on medical advertising have been gradually relaxed. The Medicine Advertising Board reevaluated the guidelines so as to provide more flexibility in the content of advertisements, and also agreed to accord special attention in expediting the applications for publications of advertisements from the APHM. In June 2005, it was announced that medical practitioners and institutions were allowed to advertise their services with immediate effect, and allowed to publish their names, disciplines, places of practice, credentials and photos, in newspapers, websites and telephone directories, although the information still has to be submitted to Medicine Advertisements Board for vetting.” (Leng, 2010)

It is reported that statistics availability on medical tourism in Malaysia is poor and many hospitals do not provide the data that the MOH requests since the MOH has no legal backing to compel the hospitals to produce statistics. The statistics that are available are stated to indicate that “…revenue from foreign patients in Malaysian private hospitals has seen an increasing trend. Eight private hospitals reported an increase of 197 percent in revenue from foreign patients between 1989 and 2001. From 2000 to 2001, ten private hospitals reported an increase in number of foreign patients from 56,133 to 75,210 (an increment of 34 percent), and a corresponding increase in income generated from RM 32.6 million to RM 44.3 million (an increment of 36 percent).” (Leng, 2010)

Leng (2010) reports that the “…uptrend in medical tourism revenue has continued…” Medical tourists in Malaysia are stated to be such that can be divided into two groups: (1) the middle and upper classes from countries where ‘quality healthcare services are not available; and (2) those from developed countries with long waiting list and services that are not affordable. (Leng, 2010) It is reported as well by Leng (201009) that the ‘Silver Hair Programme’ was introduced in 1988 as a scheme to lure “wealthy elderly Europeans and Japanese aged 50 years and above” to Malaysia for medical services. It did not succeed however, it is reported that in 1999, this program was expanded and by February 2001, “only 482 tourists has participated in the programme.” (Leng, 2010) The program was restructured into ‘Malaysia, My Second Home’ and the age limit removed although individuals younger than 50 years of age had to show a fixed income of less that RM 7,000 (single) or RM 10,000 (couple) as well as make a deposit of at least RM 100,000 (single) or RM 150,000 (couple). Those ages 50 or older had to fulfill just one of these criteria. This program provides foreigners with a five-year multiple entry visa and are allowed to purchase property above RM 150,000. This program succeeded in drawing 2,834 applications between 2002 and 2004 and it is reported that “of the 3,000 or so participants, most come from Britain, which has a historical link to Malaysia and from other neighboring countries – China, Indonesia, Singapore, and Taiwan.” (Leng, 2010) Stated to be a group that figures prominently in this program are the Chinese accounting for 1,332 applicants in 2003. (Leng, 2003) It is reported that the MMSH is under the Ministry of Tourism and Ministry of Housing’s jurisdiction as well as the local government, which reflects the two primary motivations of this program.

Leng (2010) states that medical tourism development in Malaysia is a “fairly recent phenomena, compared to that in countries such as Costa Rica, Cuba, and Singapore, which have long had people from surrounding regions come in for medical treatment. Currently, Singapore and Thailand are Malaysia’s closest regional competitors in medical tourism, while India, with the Apollo chain of hotels, is also becoming an important player. Like the Malaysian government, the Singaporean and Thai governments have played a dominant role in developing, regulating and promoting medical tourism.” (Leng, 2010) The 1997 financial crisis was critical for healthcare corporations in Malaysia with domestic markets experiencing sharp contraction and profit margins plunging with balance sheets in the red and corporations seeking out new markets in foreign countries. (Leng, 2010, paraphrased)

The development of medical tourism kept the healthcare corporations of out jeopardy and this is stated to be reflected “in the way that their expansion since then has been linked to a regional integration, as well as an intense focus on medical tourism, which makes up an increasing proportion of their businesses.” (Leng, 2010) It is reported that the regional integration “has primarily been conducted across Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore, although India, Philippines, the Middle East, and several other countries are also involved.” (Leng, 2010)

Commoditization of healthcare involves an emphasis on marketing and is an activity that is used in procuring patient/customers and since regulations on advertising have been liberalized aggressive marketing strategies are being used by medical establishments to sell their services and products abroad. There has also been an increase in the emphasis on quality and benchmarking and standardization has enabled increases in quality.

Leng (2007) reports that the process of accreditation and standardization is meant “…to inspire trust and confidence among consumers all over the world, no matter from which country or region.” Creation of customers or consumers is an essential feature of the commoditization process in the healthcare market. Leng (2010) states “In the medical tourism marketplace, healthcare users are presented with a plethora of options – listings of clinics and hospitals, with information on the technology and treatment offered, and the specialists who are in attendance. These are provided through websites, printed materials, and marketing agents.”

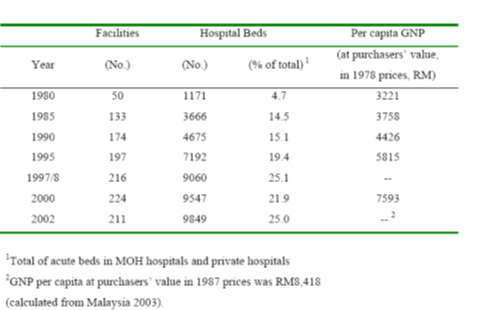

Figure 2

Private Medical Facilities and National Income

Source: Leng (2010)

Conclusion

Medical tourism is expanding and growing throughout the world greatly driven by globalization. Medical tourism in Malaysia is expanding and growing as well and the government providing support and strategically planning for success of the medical tourism industry. The medical tourism industry in Malaysia is highly organized and orchestrated and the industry is becoming well-established drawing patients throughout the world to its facilities.

References

(ASEF) Workshop on ‘Pensioners on the Move: Social Security and Trans-border Retirement Migration in Asia and Europe, 5-7 January 2006, Singapore.

Ang, Elaine (2009) Malaysian Medical Tourism Growing. The Star 14 Feb 2009. Retrieved from: http://biz.thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?file=/2009/2/14/business/3245091&sec=business

Bookman, MZ and Bookman, KR (2007) Medical Tourism in Developing Countries. Macmillan, 2007. Retrieved from: http://books.google.com/booksid=HCR23vpDC74C&dq=Global+medical+tourism&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Brown, Frances and Hall, Derek (2008) Tourism and Development in the Global South: The Issues. Third World Quarterly Vol. 29, Issue 5. Retrieved from: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~db=all~content=a793875548

Caplan, Richard (1989) The commodification of American health care, Social Science and Medicine, 28(11):1139-1148.

Chee Heng Leng and S. Barraclough (Forthcoming) The growth of corporate health care, in Chee HL and S Barraclough (ed) Health Care in Malaysia. Routledge-Curzon Malaysian Studies Series.

Department of Statistics (1977) Population Census of Malaysia 1970: General Report(Volume 1). Kuala Lumpur: Department of Statistics, Malaysia.

Department of Statistics (2002) Yearbook of Statistics 2002. Kuala Lumpur: Department of Statistics, Malaysia.

Frost & Sullivan: Malaysia’s Medical Tourism Industry has Healthy Vitals (2010) Frost & Sullivan. 14 Apr 2010

Garcia-Altes, Anna (2005) The development of health tourism services, Annals of Tourism Research, 32(1):262-266.

Gupta, Radeshyam (2011) Malaysia Medical Tourism Outlook 2012. 26 Oct 2009Market Research Reports. Retrieved from: http://businessresearc.wordpress.com/2009/10/26/malaysia-medical-tourism-outlook-2012/

Hopkins, et al (2010) Medical Tourism Today: What is the state of existing knowledge? Journal of Public Health Policy 31. Retrieved from: https://secure.palgrave-journals.com/jphp/journal/v31/n2/full/jphp201010a.html

Kaveny, M Cathleen (1999) Commodifying the polyvalent good of health care, Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 24(3):207-223.

Keaney, Michael, (1999) Are patients really consumers? International Journal of Social Economics, 26(5):695-704.

Khoo, Leslie (2003) Trends in foreign patient admission in Singapore, Ministry of Health Singapore Information Paper 2003/01.

Leng, Cheng (2010) Medical Tourism and Policy Implications for Health Systems: A Conceptual Framework form a Comparative Study of Thailand, Singapore and Malaysia. Globalization and Health. Retrieved from: http://www.globalizationandhealth.com/content/pdf/1744-8603-7-12.pdf

MacReady, Norra (2007) Developing Countries Court Medical Tourists. The Lancet, Vol.369, Issue 9576. Retrieved from: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2807%2960833-2/fulltext

Malaysia (1986) The Fifth Malaysia Plan 1986-1990. Kuala Lumpur: Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department, Malaysia.

Malaysia (1996) The Seventh Malaysia Plan 1996-2000. Kuala Lumpur: Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department, Malaysia.

Malaysia (2003) Mid-Term Review of the Eighth Malaysia Plan 2001-2005. Kuala Lumpur: Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department, Malaysia.

Medical Tourism in Malaysia profiled in Indonesian magazine, Urban Style ‘(2011) Urban Style 14 Jan 10“. Retrieved from Malaysiahelthcare.com: http://www.malaysiahealthcare.com/14012011.htm

Melaka, Malaysia (2003) Health tourism in Melaka: A comprehensive guide to medical and health services in the historic state of Melaka. Melaka State Government, Malaysia.

Ministry of Health (MOH) (2002a) Annual Report 2002. Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Health.

Ministry of Health (MOH) (2002b) Malaysia’s Health 2002: Technical Report of the Director-General of Health Malaysia 2002. Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Health.

Ministry of Health (MOH) (2003) Malaysia’s Health 2003: Technical Report of the Director-General of Health Malaysia 2003. Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Health.

Ministry of Health (MOH) (various years) Annual Report. Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Health.

Ministry of Tourism, Malaysia (undated) Malaysia: My Second Home. Advertising brochure, 7 pages.

Patients Without Borders:an Overview of the Medical Travel Industry in Asia, Its Challenges and Opportunities (2007) Unescap, EGM Bangkok, 9-11 October 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.unescap.org/esid/hds/lastestadd/medicaltbkgdpaper%5Bfin%5D021007.pdf

Pellegrino, Edmund D. (1999) The commodification of medical and health care: The moral consequences of a paradigm shift from a professional to a market ethic, Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 24(3):243-266.

Penang, Malaysia (undated). Heal and Holiday: Your Guide to Medical Care. Second Edition. A Penang Medical Tourism Project in collaboration with the Penang State Government. Advertising brochure produced by Pen’Ads (M) Sdn Bhd, Penang.

Public Health Institute (PHI) (1999) National Health and Morbidity Survey 1996 Volume 3:Recent Illness/Injury, Health Seeking Behaviour and Out-Of-Pocket Health Care Expenditure. Kuala Lumpur: Public Health Institute, Ministry of Health Malaysia.

Rabobank International Asia Pacific (1999) Impact of the Crisis: Immediate and Long-Term Outlook for Asian Health Care Markets. Research Consortium of Rabobank International Asia Pacific, Asia Health Ventures, and The Economist Conferences.

Radin, MJ (1996) Contested Commodities. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Schaniel, William C, WC Neale (1999) Quasi commodities in the First and Third Worlds, Journal of Economic Issues, 33(1):95-115.

SERI (Socio-economic and Environmental Research Institute) (2004) Economic briefing to the Penang State Government: Health tourism in Penang, 6(11):1-8.

Starr, Paul (1982). The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry. New York: Basic Books.

Stoeckle, John D. (2000) From service to commodity: Corporization, competition, commodification, and customer culture transforms health care, Croatian Medical Journal, 41(2): 141-143.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) (1998) (in collaboration with the Australian National University) Southeast Asian Populations in Crisis: Challenges to the Implementation of the ICPD Programme of Action. New York: UNFPA.

UOB Kay Hian Securities (Thailand) Co., Ltd. (2004) Thailand: Bumrungrad Hospital: A premier hospital with growth potential, 11 March. (http://research.uobkayhian.com)

Wong Chaynee (2003) Health tourism to drive earnings, Malaysian Institute of Economic Research (MIERSCOPE) paper, published in The New Straits Times, 19 April 2003.

Yamashita, Shinji and Mayumi Oto (2006). “Long-stay” tourism and international retirement migration: A Japanese perspective. Paper presented at the Asia-Europe Foundation

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee