The Gospels, Research Paper Example

The Development of the New Testament Canon: The Gospels

Introduction

Christianity and Judaism are unique among the religions of the Roman Empire in that both are religions based on the concept of having a set of scriptures, a set of written works that define what believers are to believe. Pagan religions of that time didn’t ask their members to believe any specific creed; they were merely asked to perform appropriate rituals at appropriate times. Other religions were tolerated and accepted as long as they didn’t interfere with participating in state-sponsored religious events, worshipping the emperor, and so on (Ehrman, 2003, pp. 91-92).

Jews, and later Christians, were different. Instead of worshipping many gods and being tolerant of all others, Jews insisted on worshiping only one God. Instead of having a mere ritualized worship attached to no specific doctrine, Jews had a set of writings from Moses (the Pentateuch) and other sacred writings which Jews were to study and learn from. As Christianity splintered from Judaism and became its own religion, the Jewish tradition of having a set of sacred scriptures carried over into the new religion. Believing in the scriptures is what defined Christians; not believing in them defined non-Christians. In effect, Jews and Christians in the Roman Empire invented the concept of heresy. No doubt that was in part the result of being a minority, persecuted sect, in which it was essential to be able to define “friends” an d “enemies,” but whatever the root cause, heresy was born with Christianity (Ehrman, 2003, pp. 92-94).

To be able to define unacceptable heretical beliefs, it was necessary to clearly define acceptable ones, and that is where a canonized Bible was required. The scriptures in the Christian Bible define acceptable beliefs and the proper way of living for Christians. The consolidation of the New Testament canon was carried on virtually simultaneously with the canonization of the Jewish Hebrew Bible, and both efforts literally took centuries (Patzia, 2011, pp. 24-44). The Roman Christian New Testament eventually was defined as 27 books consisting of the four gospels, the Acts of the apostles, a set of epistles, and the revelation of John. The history of the development of the Christian canon is too vast to dig into in this brief paper, so the focus here will be on the four Gospels: the books of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

Writing the Gospels

While as many as 10% of the population of the Roman Empire was probably literate, the early Christian communities in Judea almost certainly had far lower literacy rates (Freeman, 2009, p. 73). Christianity thus almost certainly began as an oral tradition rather than a literary one (Freeman, 2008, pp. 41-42). It also seems likely that all the gospels were written to be read aloud, much as Greek epic poetry was designed to be oral rather than read silently. It has been suggested that some if not all of the gospels were designed for dramatic effect during recitation, just as with epic poetry(Freeman, 2009, p. 73). Because of this, it may be best to read each of the gospels as a whole, rather than pulling out individual verses, in order to understand the overall story each gospel writer intended.

It is also certain that the authors of the gospels did not sign their work; the names Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were assigned the gospels decades to centuries after they were written. It is not until approximately185 that Irenaeus assigned names to the gospels that determined a fixed “authorship” of the gospels. The validity of those assignments is somewhat controversial in historical biblical scholarship today.

Furthermore, none of the gospels were written contemporaneously with the life of Jesus. As is noted below, estimated dates of the composition of the four gospels ranges from as early as the mid-first century to as late as the early second century (Carrier, 2000). Since all but the gospel of John seem to allude to the Roman capture of Jerusalem, which happened in 70, it is believed that all were written after that date (Carrier, 2000). Yet the four canonical gospels weren’t the only such books circulating among Christian congregations in the first century. By the second century, there were possibly as many as twenty or more “gospels” circulating among the various Christian churches.

Ehrman (2009, pp. 104-107) points out that the authors of the canonical gospels, which were originally written in highly literate Greek, do not match well the disciples of Jesus. Jesus drew his disciples from the lower classes of Judean society—fishermen, for example, with only Matthew being a little higher up the economic ladder. With Judean literacy rates being as low as they were, it is highly unlikely that any of the twelve apostles could read or write, certainly not in literate Greek. For this and several other reasons—including that the authors of the gospels do not actually claim to be the persons identified by later scribes and scholars as “Matthew,” “Mark,” “Luke,” and “John,” and the fact that none of the gospels are written in first-person—the authorship of all four of the gospels has to remain uncertain.

The Gospel of Mark

The earliest gospel, probably Mark, was not written until just before 66 A.D (Coogan, 2010); however, other scholars place its composition between 50 and 70 AD (Zondervan, 2010, p. 1620) and still others more tightly define its origin as between 65 to 70 AD (Patzia, 2011, pp. 53-54). The consensus of most scholars is that Mark was the first of the canonical gospels to be written, and a source for both Luke and Matthew. (This will be discussed in more detail in the section The Source of the Gospels: The Synoptic Problem.) Thus, Mark most likely was written some three to four decades after the death of Jesus.

It is also not certain who the author of Mark is, since Mark, like John, was a common name in the first and second centuries. The first assignment of a specific author to this gospel was made by Irenaeus c. 185, who claimed that the author of this gospel was John Mark, companion to Peter and an evangelist in his own right (Freeman 2009, p. 74; Coogan, 2010, p. 1791). Ehrman (2009) makes the point, however, that nowhere does the author of the gospel claim to be Mark, and certainly does not claim to be that specific Mark.

The Gospel of Luke/The Acts of the Apostles

The gospel of Luke was probably written sometime around 85 (Patzia, 2011, p. 54). Scholars, however, are in disagreement on this date. Although it clearly was written sometime after Mark since it drew upon Mark as a source, it could have been written as early as 70 or as late as 95; there is no clear way to determine an accurate date at this time (Coogan, 2010, p. 1827).

Traditionally, Luke is believed to have been a physician and traveling companion of Paul; the same author is assumed to have written the Acts of the Apostles, which is considered the sequel to the gospel of Luke (Coogan, 2010, pp. 1827-1828). Luke is also believed to be a Syrian from Antioch, but there are no other details of his life on record (Coogan, 2010, p. 1827). The traditions that describe Luke in these terms can be dated only back to the end of the second century, at least a century after Paul lived, so their reliability is questionable. Furthermore, there is little real evidence to support comparing the author of the gospel to the physician who was the traveling companion to Paul (Coogan, 2010, p. 1827).

It’s also unclear where the gospel was written. It is traditionally ascribed to Antioch (Luke) and Rome (Acts), though Coogan (2010, p. 1827) claims that virtually any Greek-speaking city in the Roman world is a possibility for its place of composition.

The Gospel of Matthew

Like the gospels of Mark and Luke, the date of composition of Matthew is unclear. References in the text to the Jewish Revolt against Rome imply that it must have been composed after about 70, and references to the gospel in other texts make it clear that it could not have been composed any later than the very early second century. Most scholars appear to accept a date of approximately 80 to 90 as the most likely date of composition (Coogan, 2010, pp., 1748-1749; Patzia, 2011, p. 54).

The authorship of Matthew and its association with the apostle is a presumption that is highly controversial (Zondervan, 2005, pp. 1556-1557). For one thing, date of composition is late enough that the apostle would have been an extremely elderly man at the time it was written. Also, Jesus drew his apostles from the lower classes in Judea, as noted earlier, and while Matthew the apostle was a tax collector, that does not necessarily imply any literary skills (Ehrman, 2009, pp. 104-107). Thus, it is not clear which “Matthew” was who wrote the gospel—if the author actually went by that name at all.

The Gospel of John

The gospel of John probably was written around 95 (Patzia, 2011, p. 54), though some authors assign a slightly earlier date around 90 (Zondervan, 2005, pp. 1718-1719). This is, almost universally accepted as the latest of the four gospels. Coogan (2010, pp. 1879-1881) notes that while the author is traditionally ascribed to the apostle John (Jesus’s “beloved disciple”), it is much more likely that the author is a disciple of John rather than John himself. Coogan (2010, p. 1879) also reports that the John of the canonical gospel is no longer considered by scholars to be the same author as John of the Revelation of John.

Although some of the content of John is similar to that in the synoptic gospels, the general message of John is quite different from those books. While the synoptic gospels have a significant amount of overlap, and while the author of John was clearly familiar with those stories, the differences between John and the other gospels is significant. One clear example is the issue of the virgin birth of Jesus. In the synoptic gospels Matthew and Luke, Jesus was born of the virgin Mary, but that birth was otherwise just like any other human baby’s birth. In John, however, Mary is nowhere mentioned to be a virgin, and Jesus is presented as having been in existence as a divine being, co-equal with God from creation, but who simply became incarnated as a human at his birth: “And the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son” (John 1:14) (Ehrman, 2009, pp. 73-76.).

Some scholars associate the inconsistencies between John (written in the final decade of the first century) and the synoptic gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke, (written mid-first century, perhaps a quarter-century before John) are due to the evolving doctrine of the early church (Coogan, 2010, p. 1879).

The Source of the Gospels: The Synoptic Problem

Three of the gospels, Mark, Matthew, and Luke, have a substantial overlap in terms of material covered, though the stories presented are not written precisely the same across all three. These three gospels are referred to as the synoptic gospels because they can be placed side-by-side (as a synopsis) for comparison. The synoptic problem refers to the fact that much of the material among these three gospels is similar, covering more or less the same events, and yet the presentation of those events varies quite a bit across those three gospels.

It is believed that part of the reason the synoptic gospels are so similar is that they have mutual overlap. For example, Patzia (2010, pp. 72-74) points out that Matthew includes approximately 90% of Mark, but is about 50% longer, so significant additional material must have come from somewhere else. Luke is even longer than Matthew, and includes about 57% of the material in Mark. Furthermore, there are approximately 230 verses that are similar between Matthew and Luke, and which explain the same events similarly (Patzia, 2010, pp. 72-74). Yet the presentations of these overlapping events sometimes differ substantially among them. If the gospels are the inspired Word of God, how is it that they contradict each other? Shouldn’t the same events be described more or less the same across all three canonical gospels?

As one of many illustrations, consider the birth of Jesus. As described in Ehrman (2009), Jesus is a divine entity, becoming human only at birth in John. In Matthew and Luke (but not in John), Jesus is born of a virgin mother. ( Mark makes no mention of Jesus’s birth at all.) Apparently, Matthew’s virgin birth concept was an attempted to conflate Jesus with a Messiah prophesied by Isaiah, although this apparently was based on a mistranslation of the Hebrew for “young woman” in to the Greek “virgin” (Ehrman, 2009, pp. 73-75).

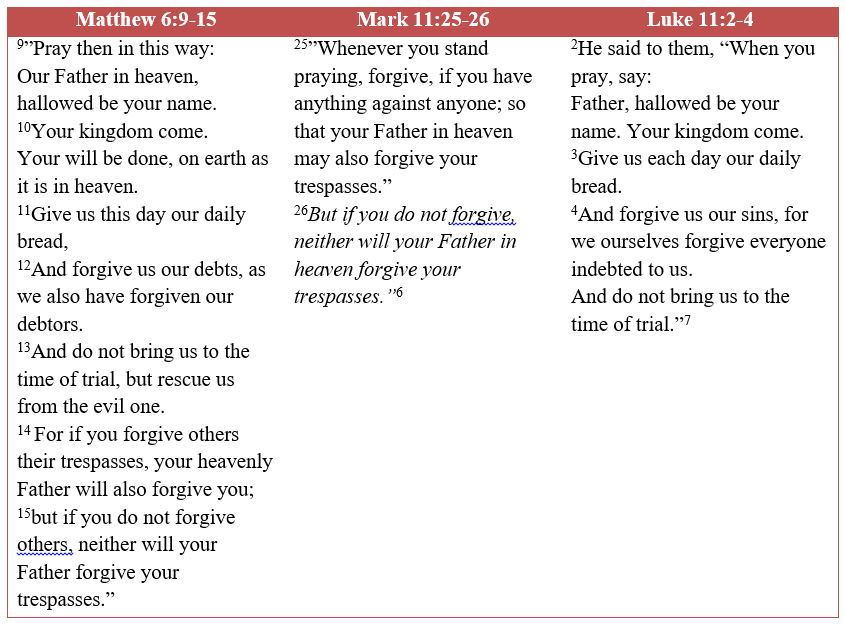

As a second example, Patzia (2011, pp. 68-80) notes that the Lord’s Prayer occurs in three different forms among the three synoptic gospels. The words of the prayer, as presented in the New Revised Standard Bible (Coogan, 2010) are noted in Table 1 for each of the synoptic gospels. Even a casual reading can spot key differences among these three prayers.

Table 1. The Lord’s Prayer as presented in each of Matthew 6: 9-15, Mark 11: 25-26, and Luke 11:2-4, New Revised Standard Edition (Coogan,2010).

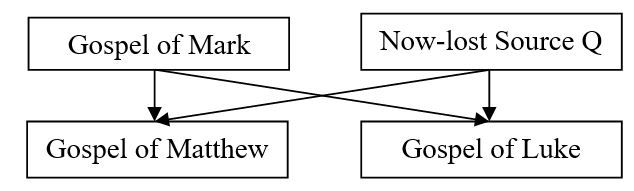

Two leading form-criticism theories of the source of the synoptic gospels exist. In the simpler one, the two-document hypothesis, Mark, as the earliest gospel, is a key source. Luke and Matthew draw heavily from Mark and were written after Mark. However, both of them also incorporate similar material not drawn from Mark; this is posited to be a now-lost document, labeled “Q.” (Patzia, 2011, pp. 72-74). Figure1 illustrates this hypothesized relationship among the sources.

Figure 1. The two-document hypothesis of the sources of the synoptic gospels (Patzia, 2011, pp. 72-74).

In the two-document hypothesis, the now-lost source document Q and Mark are taken as early sources for both Matthew and Luke, although both authors reworked the source material to make their individual points.

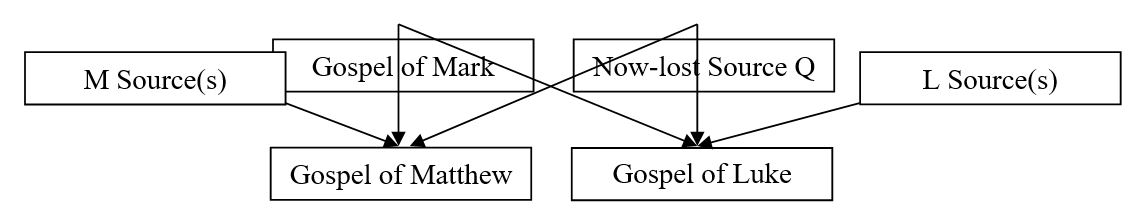

A second, more complex hypothesis is the four-document hypothesis, illustrated in Figure 2. In this theory, originally proposed by H. L. Streeter and described in both Coogan (2010, pp. 1744-1745) and Patzia (2011, pp.75-76), Matthew and Luke drew from both Mark and the Source Q document, but also drew material from two other independent sources, with Matthew drawing from a hypothesized M document and Luke drawing from a hypothesized L document, with each of the M and L documents possibly being multiple documents rather than single sources.

Figure 2. The four-document hypothesis in which Matthew drew information from source document(s) M, and Luke drew information from source document(s) L, in addition to drawing from both Mark and hypothesized Source Q (Coogan, 2010, pp. 1744-1745; Patzia, 2011, pp. 75-76).

Conclusions

As early as the end of the first century, it is possible that the four gospels were nearing canonical status. Certainly, there is evidence that they were widely distributed and quoted. A Roman bishop named Clement apparently quoted extensively from the Sermon on the Mount, though it is not clear whether Clement was quoting from the written gospel, or from an oral tradition (Perrin, 2007). Even stronger evidence supports the gospels as being in wide circulation by 125 (Perrin, 2007). Finally, by around 170 to 190, the Muratorian fragment provided the earliest known canonical list, with the four gospels established as the start of the New Testament (McGrath, 190/2011).

Thus, by the end of the second century, the four gospels were considered canonical books, though the entire set of books in the New Testament was not established for two more centuries (Elliott, 1997).

Despite their early adoption as part of the Christian canon, the authorship of each of the four gospels is in question, as is the date of their composition. Worse, there are inconsistencies among the gospels—some even flat-out contradictions—that call into question the validity of the four gospels.

Creating a canon of scripture provided the new Christian religion with a documented set of acceptable beliefs. Patzia (2011, pp. 64-66) explains why it was so important to generate a canonized set of books for Christians. The reasons provided include that the gospels were designed to meet key needs of the early church, especially including the need to evangelize gentiles and unbelievers. By providing dramatized stories about Jesus, the apostle writers (whoever they were) provided needed tools to expand the church . Furthermore, a half-century after the death of Jesus, the eyewitnesses to the events of his life were beginning to die off, so it became more important to document their stories before they were lost forever. Additionally, the gospels, along with the other books that would eventually be canonized, provided a means of educating members of the church about appropriate beliefs and ways of living. These reasons demanded that a canonized set of gospels be produced (Patzia, 2011, pp. 64-66).

While the authorship may be unclear, and the dates of composition uncertain, and despite the variations and discrepancies among them, the four canonical gospels have provided a guide and an inspiration to Christians for nearly two millennia. They have also effectively served the purposes outlined by Patzia in terms of education, evangelism, documentation, and inspiration.

References

Carrier, R. (2000). The formation of the New Testament. Web. Accessed 12-May-2011. Retrieved from: http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/richard_carrier/NTcanon.html

Coogan, M. D. (Ed.) (2010). The New Oxford Annotated Bible: Fully Revised Fourth Edition: New Revised Standard Version with the Apocrypha: An Ecumenical Study Bible. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Ehrman, B. D. (2003). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Ehrman, B. D. (2009). Jesus, Interrupted: Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible (and Why We Don’t Know About Them). New York, NY: HarperOne.

Elliott, J. K. (1997). Manuscripts, the codex, and the canon. Journal for the Study of the New Testament, 19 (63), 105-123.

Freeman, C. (2009). A New History of Early Christianity. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Freeman, C. (2008). A. D.381, New York, NY: The Overlook Press.

McGrath, A. E. (Ed.) (c. A.D. 190/2011). The Muratorian fragment on the New Testament canon. In: The Christian Theology Reader, 4th Edition, Ed. Alister E. McGrath. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 68-69.

Patzia, A. G. (2011). The Making of the New Testament: Origin, Collections, Text & Canon. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

Perrin, N. (2007). No other gospel. Christian History and Biography, Fall 2007 (96), 27-30.

Zondervan. (2005). New International Version Archeological Study Bible: An Illustrated Walk through Biblical History and Culture. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee