Autoimmune Hepatitis, Research Paper Example

Outline

Introduction

- Description

- Epidemiology

- Clinical signs and symptoms

- Diagnosis

- Prognosis

Immunological concepts underlying the disease

Therapy and management

Conclusion

- Current Trends

Abstract

The purpose of this document is to give a precise account of autoimmune hepatitis. Research pertaining to its epidemiology; clinical symptoms; immunological concepts underlying the disease; therapy and management as well as current trends will be presented in this document.

Medicine and Health: Autoimmune Hepatitis

Introduction

Description

Auto immune hepatitis is a liver disease, which occurs as a reaction to the body’s defense mechanism responding to invasion of foreign organisms on liver cells. There is usually a significant increase in activity of the class 11 human leukocyte antigen (HLA) on hepatocytes. Predisposing factors could be acute liver infection or merely genetic in origin. There are four subtypes of the disease namely; positive ANA and SMA presents with elevated immunoglobulin G; positive LKM-1 mostly found in teenagers and girl children LKM-2 or LKM-3; positive antibodies against soluble liver antigen and no autoantibodies detected (~20% (Bogdanos, Invernizzi, Mackay & Vergani, 2008). See Appendix 1

Epidemiology

There is an incidence of 1-2 per 100,000 yearly of autoimmune hepatitis cases and a prevalence of 10-20/100,000 internationally. Even though the disorder can occur at any age adolescent females are mostly affected. Associating conditions include diabetes type 1; proliferative glomerulonephritis; thyroiditis; Graves’ disease; Sjögren’s syndrome; autoimmune anemia and ulcerative colitis. Two types of the disease are prevalent; types 1 and 11. Type 1 is mostly common to people living in North America and can occur at any age while type two is less common and affects girls between the ages of 2-14 years old(Washington, 2007).

Further research conducted by Boberg (2002) revealed that incidence and prevalence varies with ethnicity and geographic locations. Incidence of type 1 among Caucasian Europeans and North Americans was 0.1 to 1.9/100,000/yearly. Japanese were less likely to contract the disease. Notably, regions of the world, which had a high incidence of viral hepatitis the incidence of autoimmune hepatitis was much lower. It was discovered also that type 11 was more prevalent in Southern Europe than other parts of the continent and world. This researcher concluded that there is a high susceptibility among white Europeans and North Americans (Boberg, 2002)

Clinical signs and symptoms

Upon physical examination patient affected by the diseases will manifest with sign and symptoms first of fatigue; an enlarged liver, jaundice, purists associated with skin rashes; joint pain; abdominal discomfort; abnormal blood vessels visible upon inspection of the skin; spider angiomas, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, pale or gray-colored stools and dark urine (Bogdanos et.al, 2008).

As the condition progresses researchers have discovered that ascites develops, mental confusion; dry eyes and mouth; liver scarring; hemolytic anemia; puffy features; absent or diminished menstrual flow; pigmented abdominal striae and increased facial hair. Often these signs and symptoms go un-noticed for some months until the disease becomes progressive and the patient seeks medical attention. They can also gimmick other such as primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis (Bogdanos et.al, 2008).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis requires a combination of diagnostic techniques inclusive of clinical assessment; laboratory test and histological investigations. Characteristic features of the disease must first be identified upon clinical analysis, which includes signs and symptoms. The ability to exclude all differential diagnoses must be applicable. Interface hepatitis is the significant histologic finding of this syndrome. Portal plasma cell in?ltration is also a typical feature of the disorder. However, none of these histological findings alone can make the diagnosis accurate. A notable aspect of histology is that when portal plasma cells do not appear it does not preclude a diagnosis (Czaja & Carpenter, 1993).

Every case must be investigated thoroughly to exclude conditions that resemble the disease. There must be hereditary evaluations for history of Wilson disease, antitrypsin de?ciency, genetic hemochromatosis; hepatitis A, B, and C infections. The presence of minocycline, nitrofurantoin, isoniazid, propylthiouracil, and -methyldopa, which have entered the system through medication must be fully accounted for. Some liver injury could initiate autoimmune dysfunctions (Czaja & Carpenter, 1993).

Prognosis

There are various opinions speculations and assumptions regarding the life expectancy of autoimmune hepatitis. However, there have been no empirical studies to provide an evidence basis for them. However, assumptions are that it varies from individual to individual depending on tolerance to drug therapy and the extent relapses occur. Assumptions are that there is a 20 year life expectancy after the disease is diagnosed and treated (Czaja & Manns, 2010).

Immunological concepts underlying the disease

Immunological concepts associated with autoimmune hepatitis are closely related to the pathogenesis of this disease. Some basic traditional concepts include:-

- Immunologic features

- Autoimmunologic features

- Circulating autoantibodies

- High serum globulin concentration

- Overlap syndromes

- Circulating antibodies to nuclei

- Atypical perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

- Liver-specific asialoglycoprotein receptor antibodies

- Double-stranded DNA

- Antimitochondrial antibodies

- Liver/kidney microsomes

- Liver cytosol antigen (Baron-Faust & Buyon, 2003).

However, according to Diamantis and Boumpas (2004) evolving concepts point towards the presence of several ‘putative hepatocellular surface antigens’ (Diamantis & Boumpas, 2004), which include:-

- P450-IID6 (recognized by the anti-LKM-1 autoantibodies) a membrane bound asialoglycoprotein receptor (a liver-specific membrane protein) (Diamantis & Boumpas, 2004).

- A cytosolic UGA-suppressor tRNA associated protein (recognized by anti-SMA and anti-LP antibodies) (Diamantis & Boumpas, 2004).

- Argininosuccinate lysate and formiminotransferase cyclodeaminase (recognized by ant-LC1 antibodies) (Diamantis & Boumpas, 2004).

It was further observed that this was inconsistent with popular research where chronic AIH hepatitides patients displayed T cell hypereactivity to autologous liver antigens. Subsequently, tissue injury appeared ‘to be mediated by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells and/or by antibody-dependent cell mediated cytotoxicity’ (Diamantis & Boumpas, 2004).

Further studies conducted by Albert J. Czaja and Michael P. Manns (2010) validated traditional concepts, but highlighted the evolving immunological development within the science pertaining to autoimmune hepatitis. They addressed specific concepts related to autoantigens; molecular mimicry; genetics and alterations in the immunocyte populations.

Autoantigens

Autoantigens responses in AIH conditions are related to a numbers of cytoplasmic enzymatic reactions. In type 2 AIH the participating autoantigen is cytochrome monooxygenase CYP2D6. Homologic associations are established with hepatitis C virus, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus type 1. Research findings are highly suggestive that homologies between human CYP2D6 and viral proteins may be the predisposing immunological factors underlying AIH development in humans. This was detected in patients with an immune system that recognizes the viral antigen as belonging to body tissue or function. As such, there is a molecular mimicry. After a number of repeated exposures the body can either accept its activity as normal or a self-tolerance break down occurs manifesting as disease in AIH (Czaja & Manns, 2010).

The researchers continue to contend that a number of other substrates are recognized by autoantibodies associated with AIH. Some identified are ribonucleoprotein complex tRNP: Sec [selenocysteine] tRNA synthase by anti-SLA and formiminotransferase cyclodeaminase by anti-LC1; UGT by anti-LKM3. Liver microsomes antibodies further bind with cytochrome CYP1A2 producing autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) syndrome during an active AIH disease (Czaja & Manns, 2010).

Molecular Mimicry

When there is inadequacy regarding specificity of T-cell antigen receptor sensitivity, abnormal reactions occur because often there are multiple antigens with similar epitopes in circulation to activate CD4+T cells. As such, molecular mimicry becomes eminent in cellular interrelationships. Ultimately, expansion of liver-infiltrating cytotoxic T cells occurs. These cells create liver damage by producing antigen- sensitive plasma cells, which in turn manufacture autoantibodies (Czaja & Manns, 2010).

Genetics

Genetics has been recognized as an important contributory factor to autoimmune hepatitis. The immunological relationship is definitely unique. Immunological explanation refers to the fact that MHC is responsible for the way antigens function within the immune system by establishing immune activation. Precisely, MHC is linked to DR?, a polypeptide chain in the class II molecule category, that present antigen to CD4+ T lymphocytes (Czaja & Manns, 2010).

More importantly, ‘The DRB alleles DRB1*0301, DRB1*0401, DRB1*0404, and DRB1*0405 encode the same or similar 6 amino acid sequences (LLEQKR or LLEQRR) at positions 67 to 72 in the antigen-binding groove, and these are the alleles that affect susceptibility to type 1 AIH’ (Czaja & Manns, 2010, p. 60)

Scientists believe that DRB1*0701 affects antigen-binding groove to promote a presentation of antigens that initiate type 2 AIH. DQB1*0201 also shows a strong relationship to disequilibrium with DRB1*07 and DRB1*03. As such, it predispose towards being the main genetic determinant of anti-LKM1–related to AIH. DRB1*1301, the most vulnerable susceptibility allele in South America, is linked to protracted infection with hepatitis A virus. A further predisposition to children developing AIH with extended exposures to the antigen interaction (Czaja & Manns, 2010, p. 60). See Appendicies11 & 111.

Alterations in Immunocyte Population

Suppressive modulation of CD8+T cells is activated by T cells (CD4+CD25+ Treg cells). This occurs through proliferation causing interferon gamma to be produced increasing secretion of IL-4, IL-10. At the same time the growth factor ? is transformed creating a sub population of Treg cells, which do not contain any CD127. However, CD4+CD25+CD127 cells are expected to have more regulatory potential than CD4+CD25+ Treg cells. Importantly, in AIH conditions there is a marked decreased in Treg cells (Czaja & Manns, 2010, p. 60).

T (NKT) which creates natural deaths in humans also regulates immune responses in the body. Studies show where NKT is also deficient in AIH conditions although they are found in normal liver regulating cytotoxic levels. This process is conducted by activating apoptosis in hepatocytes which have been already has structural alterations. Studies have revealed that NKT cells contain granzymes and perforin active participants in apoptosis. This makes NKT cells very cytotoxic. Besides, they contain very effective anti-inflammatory and immune suppressive properties (cytokines – IL-4). NKT cells can counterbalance inhibitory and stimulatory receptors, but are dependent on intrinsic factors to signal responses. Precisely, These NKT cells are responsible for differentiation of Treg cells, which ultimately could initiate an autoimmune condition such as AIH. Conclusions drawn by researchers are that with the complexity of NKT activity in the autoimmune mechanism there is no doubt that these cells play a great role in the AIH development (Czaja & Manns, 2010).

Therapy and management

Generally, theories pertaining to therapy and treatment always make references to early detection for most favorable outcomes. Corticosteroid therapy is considered most effective in active stages of the disease, but considerations ought to be given to ethnic differences as well as genetic predisposing factors. These two criteria can greatly affect how patients respond to treatment. Prednisolone is a recommended corticosteroid, which is often prescribed and most patients respond to it quickly. It could be administered alone or in combination with other steroids such as azathioprine. This drug helps to reduce symptoms as well as liver inflammation in most patients. Most importantly, it prevents hepatic fibrosis, which increases the 20 year life expectancy prognosis (Czaja & Manns, 2010).

All patients do not respond to glucosteroids or azathioprine. When this occurs low doses of alternative immunosuppressives such as cyclosporin, mycophenolate, cyclosporin, tacrolimus or methotrexate is prescribed as an alternative. In some cases liver transplant may be recommended, but studies show where some patients react negatively to this therapy also (Bogdanos et.al, 2008). However, the objective of treatment should be to relieve symptoms and reduce liver damage, which can result in death.

Hence, therapy should continue until normal liver test results appear. These include, ‘serum aspartate aminotransferase, ALT, bilirubin, and ?-globulin levels’ (Czaja & Manns, 2010). Doctors are careful in their management of these cases by paying attention to whether normalcy in liver tissue is restored because this reduces the relapse incidences from 86% – 60 % after withdrawal from drug therapy. With astute management it can get as low as 20% (Czaja & Manns, 2010).

However, despite effective management, studies have shown where treatment can achieve only 40% recovery rate. Once the person has been diagnosed with the disease at any time relapses could occur. Therefore, individualizing treatment is another strategy, which improves survival rates and reduces relapses. In this way the doctor can cater treatment to meet the patient’s specific needs according to tolerance of medications. Most patients show significant progress within 12 months (Czaja & Manns, 2010).

Further studies have revealed that 70% of patients who respond favorably within 24 months, and a great percentage show normal serum ALT levels within 3 to 6 months. Long-term maintenance treatment is administered to patients who show improvement after 24 months, but according to their age and liver competence can be taken off of drug therapy. They continue on a low dosage. The over 60 age group tends to respond better than younger ones 40 years and under. There is a 95%-65% response rate (Czaja & Manns, 2010). See Appendix 1V.

Conclusion

Current Trends

Current trends focus early detection; improving management of the disease through researching better drug therapies and managing relapses. Studies have revealed that patients can be treated with cyclosporine if they exhibit intolerance to corticosteroids. It addresses two aspects of the disease relapses and intolerance itself. Many patients relapse after becoming steroid resistant. Other drug experiments and trials are conducted with Mycophenolate mofetil is a purine antagonist and Budesonide as a first time drug therapy intervention (Czaja & Manns, 2010).

A significant current trend pertains to ‘Emerging Cellular and Molecular Interventions.’ Cellular and molecular therapies are developing to maintain adaptive immune defenses, limit treatment-related complications, ‘ensure prompt onset of action, and allow tight regulation of the duration and intensity of immunosuppressive effect. These interventions are feasible because of improved understanding of the critical pathogenic pathways of AIH’ (Czaja & Manns, 2010).

Adoptive transfer approaches have allowed Treg cells expansion freshly cultured to correct deficiencies in AIH patients. Already corticosteroids therapy has proven great success in improving Treg cell function. Consequently, scientists believe that by targeting antigen-specific Treg cells could greatly assist in early detection of deficient populations thereby limiting relapses and provide remarkable advancement in the scientific management AIH (Czaja & Manns, 2010).

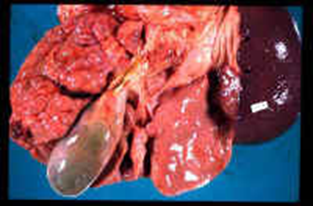

Appendix 1

(Hind & Hisham, 2011, p. 242)

The above illustration shows changes in liver cells of a 16 year old female patient with autoimmune hepatitis for 3-4 years, which has developed into the cirrhotic, stage (Hind & Hisham, 2011).

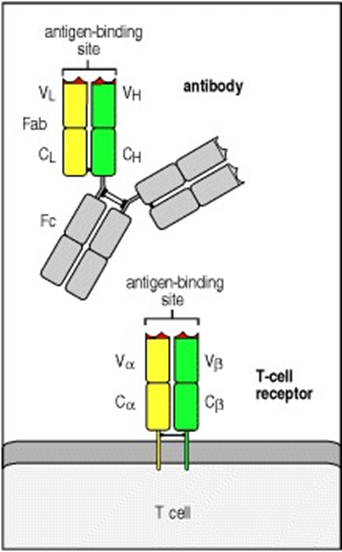

Appendix 11: T-cells antigen binding grove

(Janeway & Travers, 2001) Chapter 5.

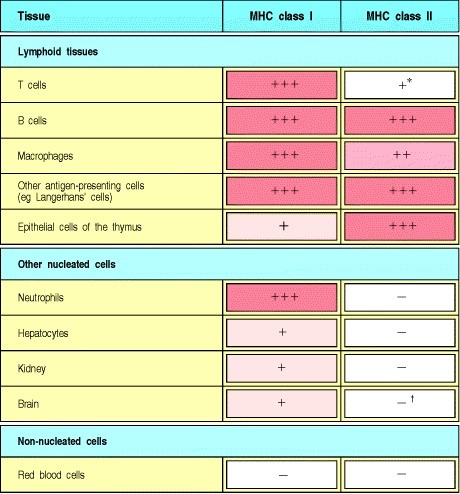

Appendix 111

(Janeway & Travers, 2001). Chapter 5

Chart showing the expression of MHC molecules difference between tissues

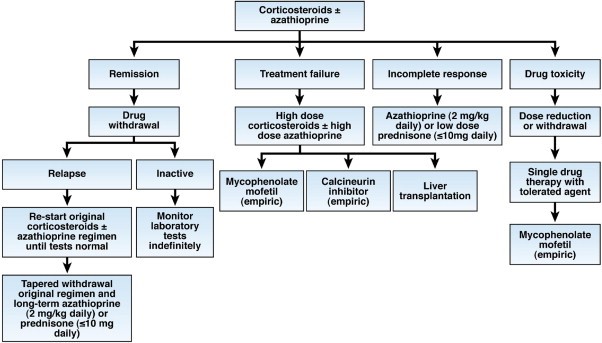

Appendix 1V Treatment

Flow chart of therapy for AIH.

‘Patients are given only corticosteroids or a lower dose of corticosteroids in combination with azathioprine (preferred initial regimen). The outcomes of initial therapy dictate changes in the treatment strategy’ (Czaja & Manns, 2010).

References

Baron-Faust, R., Buyon, J. (2003). The Autoimmune Connection : Essential Information for Women on Diagnosis, Treatment, and Getting On with Your Life. McCraw-Hill

Bogdanos, P. Invernizzi, P. Mackay, R. Vergani, D. ( 2008). Autoimmune liver serology: Current diagnostic and clinical challenges. World J. Gastroenterol, 14 (21), 3374– 3387.

Boberg, K. (2002). Prevalence and epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis.6(3):635-47

Czaja, A., & Carpenter, A (1993). Sensitivity, speci?city and predictability of biopsy interpretations in chronic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 105, 1824-1832

Czaja, A., Manns, M.(2010). Advances in the Diagnosis, Pathogenesis, and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis. Gastroentorology. 139(1), 58-72

Diamantis, I., Boumpas, D. (2004). Autoimmune hepatitis: evolving concepts. Autoimmun Rev. 23(3):207-14.

Hind, I., & Hisham, A. (2011). Mycophenolate Mofetil as a Rescue Therapy for Autoimmune Hepatitis Patients Who Are Not Responsive to Standard Therapy. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 5(4):517-522.

Janeway, C., & Travers P, (2001). Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. (5th edition). New York: Garland Science.

Washington, K. ( 2007). Autoimmune liver disease: overlap and outliers. Mod. Pathol. 20 Suppl 1, S15–30.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee