Can Stage of Change Predict Clinical Outcomes? Capstone Project Example

Introduction

“Globesity”—the pandemic of people being overweight and/or obese—is a public health problem.1 More than 115 million people suffer from obesity-related problems worldwide,1 including chronic cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and hypertension.2, 3 Between 2007 and 2008, an estimated 34% of Americans aged 20 years and older were overweight, 34% were obese, and 6% were morbidly obese.4 In the state of New Jersey, the prevalence of obesity in 2009 was 32%, which was comparable to the national level.5 According to the 2009 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),6 direct and indirect annual costs of obesity were reported to be as high as $147 billion. Obesity-related direct expenditures are expected to account for more than 21% of the nation’s direct health care spending by 2018.7 If the rising rate of obesity could be halted, an estimated $200 billion in health care costs could be saved by 2018.7

Healthy People is a 10-year national science-based objective to promote health and disease prevention in the American public.8 Since the late 1970s, Healthy People has set national health objectives to “meet a broad range of health needs, encourage collaborations across sectors, guide individuals toward making informed health decisions, and measure the impact of our prevention activity.”8 One of the objectives of Healthy People 2010 was to reduce the rate of obesity within the adult population to 15%. Unfortunately, no state met this goal, and the overall prevalence of obesity among U.S. adults continues to increase, as reported by the CDC in 2009.9

As part of the public health initiative, one of the goals in the Healthy People 2020 is to establish nutrition and weight management counseling in the workplace to help reduce the percentage of adults with obesity.8

The prevalence of obesity and obesity-related chronic diseases has become an occupational health concern as recognized by the National Institute for Occupational and Safety.10 Worksite-wellness programs have become an area of interest to employees and employers because of their demonstrated effectiveness in improving health benefits, not only by lowering medical costs11 but also by decreasing total health risk.2 The American Heart Association (AHA) promotes and endorses comprehensive worksite-wellness programs to address the public health crisis in the areas of cardiovascular disease and stroke prevention.12 Implementation of effective worksite-wellness programs for weight management are found to benefit both employers and employees.13,14

The AHA also recommends assessing readiness to make behavioral changes to focus the individual’s skill development as an integrated part of workplace programs.12 The transtheoretical model (TTM), one of the most commonly used models for studying behavioral change,16 is a behavioral theory used to determine whether an individual is ready to change to a healthier lifestyle.17 A study conducted from 2006 to 2008 by the Institute for Nutrition Interventions at the School of Health Related Professions (SHRP) of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ) determined the impact of a 12-week worksite-wellness program on overweight and obese employees using in-person and Internet-based approaches.15 Although the UMDNJ trial found positive changes in clinical outcomes including weight loss, changes in body fat, waist circumference, cholesterol levels, and blood pressure in both men and women,15 participants’ stages of change (SOC) were collected in the original trial but these data have not yet been explored. This is a great opportunity and is important to explore SOC. Not only this will help better design and develop interventions for worksite wellness programs, but also will facilitate health care providers to set up appropriate goals and action plans to move participants forward according to their readiness to change.

This proposed outcome study uses TTM to examine the relationship between the stage of change (SOC) regarding eating behaviors and clinical outcomes in weight and body fat percentage among overweight and obese employees in a 12-week worksite setting. The primary aim of this proposed study is to investigate how the SOC, based on the TTM, regarding eating behavior might predict the outcomes in weight and body fat percentage.

Problem Statement

Among overweight and obese employees enrolled in a 12-week worksite-wellness intervention program using in-person and Internet treatment methods at an academic health sciences university, does SOC regarding eating behavior predict changes in weight and body fat percentage at 4 time periods (baseline-week 12, weeks 12-26, weeks 26-52, and baseline-week 52), given the participants’ demographic characteristics?

Null Hypotheses

- There is no relationship between baseline SOC regarding eating behavior and weight change from baseline to week 12.

- There is no relationship between baseline SOC regarding eating behavior and weight change from baseline to week 52.

- There is no relationship between baseline SOC regarding eating behavior and change in body-fat percentage from baseline to week 12.

- There is no relationship between baseline SOC regarding eating behavior and change in body-fat percentage from baseline to week 52.

Operational Definitions

Action: For the purposes of the study, action will be defined as the fourth stage of change in the transtheoretical model.17 Action involves overt behavioral changes and requires a considerable time and energy commitment for behavioral transformation. It is the stage in which individuals change their behavior, experiences, or environment to overcome problems that have occurred within the past 6 months.17

Age: For the purposes of the study, participant age will be based on the date of birth reported by the participant on a questionnaire administered during enrollment in the worksite-wellness program.

Baseline: For the purposes of the study, baseline refers to the beginning of the intervention, week 1 of the worksite-wellness program.

Body fat percentage (body fat %): For the purposes of the study, body fat percentage is a measure of the percentage of total body weight that is from fat. Measurements were reported from a calibrated Tanita BC-418 NA body composition analyzer.18

Body mass index (BMI): For the purposes of the study, BMI is a measure of an individual’s weight in relation to height, reported as kg/m2 .19 Measurements were reported according to the Tanita BC 418 body composition output.18

Clinical outcome measurements: For the purposes of the study, clinical outcome measurements are the participants’ weight and body fat percentage.

Contemplation: For the purposes of the study, contemplation is defined as the second stage of change according to TTM.17 Contemplation is the stage in which individuals are aware that a problem exists and are thinking about making changes within the following 6 months. There is no commitment to take action at this stage.

Change in stages of change: For the purposes of the study, change in stages of change refers to the measurement of the categorical change in the stage of change model in each period between 2 time points: baseline to week 12, weeks 12 to 26, weeks 26 to 52, and baseline to week 52.

Ethnicity: For the purposes of the study, ethnicity was reported as Asian, White (non-Hispanic), White Hispanic, Black (non-Hispanic), Black Hispanic, and others.

Gender: For the purposes of the study, gender was defined as male or female at age 18 years old or older.

History of chronic diseases: For the purposes of the study, history of chronic diseases will be defined as medical conditions such as heart disease (including congestive heart failure, cardiovascular disease, and coronary heart disease), stroke, cancer, diabetes, or arthritis.20 History of chronic diseases is self-reported by participants when completing the initial wellness program questionnaire.

Individual session with RD: For the purposes of the study, individual session refers to the intervention of a face-to-face discussion between an individual participant and the study’s registered dietitian (RD) for data collection and counseling at baseline and weeks 6, 12, and 26 to establish an individual’s goals to meet his or her dietary needs and physical activity changes.18

In-person group (IP): For the purposes of the study, the IP group is defined as those participants who were provided 12 weekly face-to-face 50-minute group sessions that integrated assessment, counseling, education, questions and answers, weigh in, and interaction in a group setting on the Newark Campus.18 IP is one of the treatment characteristics.

Internet-based group (IB): For the purposes of the study, the IB group is defined as those participants who were provided 12 weekly online group sessions via an academic virtual learning platform, WebCT, on the Piscataway/New Brunswick campus.18 Participants received group sessions online and physically came to office for weigh-in once a week for 12 consecutive weeks leading by similar group sessions information as provided in IP group. IB is one of the treatment characteristics.

Maintenance: For the purposes of the study, maintenance will be defined as the fifth stage of TTM.17 Maintenance is the stage in which individuals work to prevent relapse. It is a static stage that stabilizes the achievement of the action stage.17

Obese: For the purposes of the study, obesity is defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or greater.19

Overweight: For the purposes of the study, overweight is defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of 25 or greater.19

Participant demographic characteristics: For the purposes of the study, participant demographic characteristics include age, gender, ethnicity, and history of chronic diseases.

Precontemplation: For the purposes of the study, precontemplation is the first SOC as defined by TTM.17 Precontemplation is the stage in which an individual has no intention to change behavior in the near future, that is, within the following 6 months.

Preparation: For the purposes of the study, preparation is defined as the third SOC of TTM.17 Preparation is a stage in which individuals plan to take action to change, usually within the following months. Often, individuals in this stage have attempted some action in the past and have a plan of action.17

Stages of change (SOC) in eating behavior: For the purposes of the study, SOC refers to one of the five stages of behavioral change according to TTM.17 SOC reflects participants’ readiness to change their eating behavior. The SOC regarding eating behavior for participants is obtained at four time points in this study: baseline, week 12, week 26, and week 52. SOC will be identified at each time point and then compared the change at each time period (from one time point to the next such as baseline to week 12). The change in SOC regarding eating behavior and the change in clinical outcomes (weight and body fat percentage) will be measured at four time periods: baseline to week 12, weeks 12 to 26, weeks 26 to 52, and baseline to week 52.

The transtheoretical model (TTM): For the purposes of the study, TTM is a behavioral model that describes a series of five stages of change a person goes through when adopting a new behavior: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance.17

Treatment characteristic: For the purposes of the study, the term treatment characteristic refers to participants’ assignment to either the IP or IB group.

University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ): UMDNJ is an academic health center that includes 8 schools on 5 campuses in the state of New Jersey.21

WebCT: For the purposes of the study, WebCT refers to the UMDNJ distance learning course-management system used for distance education and training. All participants in the program were familiar with WebCT system.22

Week 12: For the purposes of the study, week 12 refers to the active intervention phase and the 3-months’ participation point in the study.18

Week 26: For the purposes of the study, week 26 refers to 6 months of participation in the study.18

Week 52: For the purposes of the study, week 52 refers to a year of participation in the study.18

Weight: For the purposes of the study, weight, without shoes, was measured in pounds. A calibrated Tanita BC-418 NA body composition analyzer was used to obtain weight at baseline and weekly for the first 12 weeks, then at weeks 26 and 52.18

Limitations

This study is limited to a retrospective analysis of men and non-pregnant women between the ages of 18 and 80 years of age who were overweight or obese and participated for at least 12 weeks in the worksite-wellness program at the UMDNJ between July 2006 and September 2008.

Related Literature

Background

Because increasing weight and obesity are related to debilitating health risks, federal government agencies6,8 and national association12 have endorsed worksite-wellness programs. The AHA, in its policy statement on worksite-wellness programs for cardiovascular disease prevention in 2009, stated that such programs are “a proven strategy to prevent major health risks” such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), stroke, obesity, and hypertension.12 As part of the public health initiatives, the US Department of Health and Human Services identifies two specific worksite-related goals in Healthy People 2020.8 To improve Americans’ health, one of the objectives is target the area of physical activity to “increase the proportion of employed adults who have access to and participate in employer-based exercise facilities and exercise programs.”8 The second objective is to focus on the areas of nutrition and weight status to “increase the proportion of worksites that offer nutrition or weight management classes or counseling” and reduce the percentage of adults who are obese.8

The CDC also acknowledges the impact of health promotion at federal workplaces.23 The CDC developed the Healthier Worksite Initiative (HWI) to address workforce health promotion for its employees, including developing workplace policies consistent with wellness goals.23 These policies promote a variety of features that affect employees’ ability to make healthy choices at work, such as using stairs instead of elevators, encouraging exercise in on-site fitness centers, and preparing healthy foods in equipped break rooms.23 A meta-analysis by Verweij et al.24 demonstrated that workplace interventions including physical activity and dietary-behavior modification resulted in significant reductions in clinical outcome measurements including body weight, BMI, and body fat percentage.

The purpose of this literature review is to provide an overview of the current literature regarding worksite-wellness programs and their effect on employees’ health-related outcomes. Prior research findings are compared and contrasted with emphasis on the outcomes proposed for this outcomes-research study. Worksite-wellness program research focusing on obesity and application of the TTM in weight and eating behavioral changes are also discussed. Findings are examined in regard to the outcomes of interest in the proposed study.

Worksite-Wellness Programs and Health-Related Outcomes

Workplaces are ideal environments in which to promote health and disease prevention among employees because a typical full-time employee spends 8.7 hours—more than one-third of the day—at work.70 In the search for the related literature to review, key words included worksite-wellness program, overweight, obesity, intervention, and outcomes were used. The reviewed literature was limited to US primary studies published in the last five years (2006-2011) having weight-related outcome measures. Eight studies were found and are presented in Table 1. These nine studies15, 25-31, 68 included employees from a variety of worksite backgrounds, including schools, hospitals, universities, a weight management facility, automobile industry worksites, and a variety of other worksite settings. The duration of the wellness-intervention programs varied from 12 weeks to 2 years. The outcome measures in the reviewed studies included BMI, weight loss,15,31, 68 health-risk markers (cholesterol, blood pressure, Framingham CHD risk score), and fruit and vegetable consumption.15,27-31, 68

Worksite interventions can have a remarkable effect on health related outcomes even over relatively short time frames. Several studies demonstrated statistically significant impacts on clinical measures including BMI and cholesterol15,27,28 after only three to six months. The studies found in this literature search show that, in a wellness-intervention program as brief as 12 weeks, positive outcomes including decreased BMI, cholesterol, body fat, and waist circumference can be achieved.15,27 Milanli et al28 conducted a 6-month intervention program involving onsite health education, nutrition counseling, and physical-activity promotion and found significant improvements in body fat, HDL cholesterol, and blood pressure, as well as in quality-of-life. In the span of one year, other programs demonstrated significant changes in BMI,25,26 as well as measures such as HDL/LDL, blood pressure, fat mass, and weight loss depending on the study.26,29,31

Structure of Worksite-Wellness Programs

Comprehensive wellness programs include components of disease prevention, nutrition education, weight management, disease management, and CVD education, as well as occupational safety and health promotion.12 Tailoring health information to meet individual needs has been reported to be an effective method in nutrition intervention to prevent obesity.32 A systematic review of 47 studies by Anderson et al.33 found that a structured weight loss program, such as one including scheduled individual or group sessions, for overweight and obese employees can be effective. Across the studies in the systematic review, researchers found that employees achieved a weight reduction about three pounds and a decrease in BMI of 0.5 over 6-12 months. Based on 11 studies evaluated by Anderson et al.,33 wellness programs that utilized structured approaches had more positive outcomes than unstructured approaches.

Beresford et al. used an approach promoting activities and changes in eating (PACE) in a modified environmental framework.25 A five-phase approach, phase 1 promoted awareness of activity and healthy eating was promoted; phase 2 increased motivation and support for physical activity; phase 3 increased motivation and support for dietary changes; phase 4 established a support system for healthy diet and activity; and phase 5 supported maintenance of these changes.25 Higher BMIs in this program were associated with consumption of both soft drinks and fast food.25 In women only, higher BMIs were also associated with eating while doing other activities.25

Even relatively simple interventions can have significant impact as shown in a study by Gemson et al.26 This study took place at seven sites within the Merrill Lynch Company. Five sites served as usual care sites, and the other two sites serves as experimental sites. Subjects in the study were hypertensive employees. Participants in the usual care sites received BP and weight measurements, plus educational materials on weight control. Participants in the intervention sites received the same measurements and materials, but also received pedometers, body fat measurements, and an additional two sentences in the educational materials specifically encouraging increased physical activity. This quasi-experimental study demonstrated significant reductions in blood pressure and weight through a small, 2-sentence reminder in printed health information received in the intervention group; these sentences mentioned the importance of blood pressure control, physical activity and 10,000 steps a day of walking.26 A poster was placed in the blood pressure screening station, and registered nurses verbally stated brief messages to remind employees on the importance of exercise to help lower blood pressure. The intervention group’s pedometers were intended to help measure those 10,000 steps.26

Haines et al.27 investigated a program that encouraged an increase in walking among college faculty and staff at Ohio State University by supplying participants with a pedometer and setting up a 12-week walking wellness program, a computer education program, and weekly email reminders.27 Across the 12-week program significant blood pressure and BMI reductions were identified, but compliance with the program may have derived in part because the program was carried out in the summer time.27

Racette et al.29 performed a one-year controlled trial study across two worksites (intervention and control) at a St. Louis, MO medical center. The one-year trial compared groups at two worksites, one which received health assessments plus worksite interventions, while the other worksite received only the health assessments. The overweight and obese medical center employees in the intervention group received interventions designed to promote physical activity and healthful eating through providing pedometers, having healthy snacks available, group exercise classes, WeightWatchers® meetings, team competitions, and rewards for participation in the intervention.29 In addition, both intervention and control worksites received individualized health assessments, though the control worksite received no further information.29 While the intervention group showed greater improvement in BMI, fat mass, and Framingham risk score than the control group after one year, both groups improved in blood pressure, total HDL and LDL cholesterol values.

Furthermore, all studies included in this literature review (Table 1) integrated an intervention component designed to promote dietary, health, and physical activity.15,25-31 A specific nutrition counseling component was included in the studies by Milani et al., Terry et al., and Touger-Decker et al.15,28,31 Although a randomized control trial (RCT) conducted with employees from the L.A Unified School District by Siegel et al.30 did not show an intervention effect on waist-hip ratio, physical activity, or fruits and vegetable consumption, the researchers did find a significant reduction in BMI in participants in the intervention group that took part in such activities as improving diet, increasing physical activity, and learning stress management techniques.

Overall, the available studies in this literature review suggest generally favorable results for worksite interventions, with improvements shown over multiple clinical outcome measures such as BMI, BP, and other health measures. The most effective strategies and programs for obesity prevention are not yet well established34 because the designs of worksite-wellness programs vary from site to site based on employer interests, available resources, and employees’ needs. Such variation makes comparing and contrasting these programs difficult.

Delivery Methods of Wellness Program

The Internet is a convenient method for delivering weight loss interventions. It is estimated that as of March 31, 2011, 78% of all North Americans were users of the Internet.71 Touger-Decker et al.15 conducted a 12-week worksite-wellness program study with overweight and obese employees in a Mid-Atlantic academic health sciences center, using in-person and Internet-based approaches to determine the programs’ effectiveness on weight and cardiovascular disease risk and the effect of delivery method on the outcomes. The 12-week worksite-intervention program included individual and group sessions integrated with assessment, counseling, questions and answers, education, as well as discussions covering a variety of topics on healthy eating, physical activity, and behavior modification by a registered dietitian. No significant difference in effectiveness was found between the in-person (IP) and Internet-based (IB) groups.15 The results demonstrated the worksite-intervention program resulted in significant reductions in weight, waist circumference, body fat, and energy intake, as well as quality of life among overweight and obese employees.

Cook et al.35 also studied the effectiveness of intervention methods in implementing a wellness program. They found that web-based programs were more effective in providing diet and nutrition information to people than providing the same information in printed form. Furthermore, Terry et al.31 used a telephone-based intervention approach to examine the impact of a worksite weight-management program. Their findings indicated that individuals who kept the telephone follow-up appointments lost more weight than those who did not complete the program.31 Regardless of the delivery method—telephone, web, or e-mail, all demonstrated positive changes in terms of weight loss, dietary intake, and physical activity.15,31,36-37

DeJoy et al68 assessed the effectiveness of environmental worksite interventions alone in contrast with worksite interventions combined with individual health assessments. Participants in the second group self-selected for individually focused weight-loss interventions. This study showed no greater effectiveness with the individual health assessments than those who only received the general workplace interventions. In this study, approximately 13.5% of each of the two groups lost at least 5% of their body weight; the changes of each of the two groups overall were negligible. The authors concluded that simple worksite interventions were inadequate to stimulate significant weight reductions, even if combined with individualized health assessments.

Behavioral Change Theory for Weight Management

According to the American Dietetic Association (ADA) Evidence Analysis Library, strong evidence exists to support the combined use of behavioral and cognitive behavioral theories in facilitating modifications in weight, dietary habits, and cardiovascular and diabetes risk factors.38 Because the process of changing a behavior varies from individual to individual, time and effort dedicated to clients are not constructive when they are not ready to take steps needed to make behavioral changes. Assessing the level of readiness in behavioral change among individuals is necessary when designing weight-loss intervention programs because mastering the behaviors related to good nutrition, physical activity, and weight management are crucial to the prevention and treatment of obesity.12,34

Initial readiness is thought to be a critical state that influences the successful implementation of change because readiness for change is a complex multidimensional construct that involves both psychological and structural dynamics.39 Level of readiness, willingness to change, and self-motivation are the crucial elements that drive successful weight reduction.40 Other documented factors that influence weight reduction in individuals are weight-change desire (self-efficacy), body-shape perception, and past weight-control experience.41, 42 Thus, effective strategies need to be identified and developed to assist individuals in making realistic and optimal weight-reduction and health-related goals.

Archie et al.43 concluded that the efficacy of lifestyle interventions that promote diet change is dependent on individuals’ readiness to change their behavior. Specific goal setting for weight management can be developed according to each stage of change based on TTM because individuals in the preparation and action stages require different types of support from those in the precontemplation or contemplation stages.44 Table 2 shows examples of the goals that were established by Greence et al.45 in response to each SOC in TTM.

Table 1. Goal Setting Based on Stages of Change

| Stage of Change* | Goal Settings |

| Precontemplation | To help individuals think of the consequences of not changing the existing eating behavior that may lead to more weight gain and other health problems over a long period of time. |

| Preparation | To encourage individuals to continue to experiment and explore new ways to make changes needed to lose weight. |

| Contemplation | To assist individuals to make a decision to begin making small changes for weight change |

| Action | To support individuals to continue to keep up with current efforts to meet target goal weight. |

| Maintenance | To prevent individuals from relapsing or regaining weight. |

(* Stage of Change is a change process involving progress through a series of stages based on the Transtheoretical Model by Prochaska, adapted by this study’s PI.46)

The Transtheoretical Model

TTM is one of the most commonly used models applied to achieve behavioral change.17 The model describes how behavioral change develops in five stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. This is commonly referred to as Stage of Change (SOC).16 When someone engages in a new behavior, his or her progress is described in terms of stages of change and processes of change. The process of change includes 12 processes considered responsible for behavioral changes.17 When an individual’s SOC is identified, a process of change can be applied using appropriate intervention strategies and techniques to facilitate progression through the stages of behavioral change. Table 3 indicates each SOC and the corresponding intended change in behavior.17,46

Table 2. Description of Stage of Change and Intention to Change Behavior

| Stage of Change* | Intention to Change* |

| Precontemplation | People in this stage have no intention of behavioral change in the near future, usually measured as the next 6 months |

| Preparation | People in this stage are aware that a problem exists and are thinking about making changes within the next 6 months; there is no commitment to take action at this stage. |

| Contemplation | People in this stage are aware that a problem exists and are thinking about making changes within the next 6 months; there is no commitment to take action at this stage. |

| Action | People in this stage modify behavior to overcome problems within the past 6 months. |

| Maintenance | People in this stage are able to maintain the static stage to stabilize what has been achieved in the action stage over 6 months. In this stage, individuals work to prevent relapse. |

(* The content of the intentions to change behavior is adapted from Prochaska et al.17,46by this study’s PI)

Relapse is defined as the inability to remain in the action or maintenance stage, thereby creating a cyclical movement back to the earlier SOC. Continuing intervention can be a useful strategy to prevent individuals from reaching the relapse stage as part of a weight-management program. Specifically, the SOC model has been identified as a helpful tool in assessing the effectiveness of an intervention program to lower saturated fat intake among cardiac patients.47

Application of TTM

TTM was first applied in the area of smoking cessation in the early 1980s.48 The interest in applying TTM to treatment and prevention of obesity began to grow in the late 1990.48 While TTM had been widely applied to smoking cessation,43,49 increasing physical activity,50-53 and controlling diabetes,54 published studies over the past five years indicate that the SOC model has been largely applied to dietary change such as fruit, vegetable, and fat consumption.39,45,51,53,55-57 However, published studies exploring the relationships between SOC in terms of eating behavior and changes in clinical measurements which are specifically focused on weight and body-fat percentage among overweight and obese populations at a worksite setting, have not been identified by this study principal investigator (PI).

Table 4 provides an overview of studies published over the past five years (2006-2011) addressing the use and outcome of TTM in modifying weight and eating behavior. Seven of the primary studies reviewed were conducted in the United States, whereas one was performed in the Netherlands. The studies measured changes in healthy eating; nutrient and food intake, specifically fruits, vegetables, and fat consumption; body weight; exercise; and behavioral strategies based on the use of TTM.

Palmeira et al. conducted a 4-month intervention in overweight and obese women consisting of educational and practical components on exercise, nutrition and behavior modifications.58 The study compared transtheoretical model with three other health behavioral change theories; the transtheoretical model explained about 30% of the resulting BMI and weight loss, the maximum of any of the four health behavioral change theories.58

Johnson et al.51 used TTM to look at multiple behavior changes in overweight or obese adults over two years focusing on healthy eating, exercise, and emotional distress managing behaviors. The study showed that participants who received intervention in any of the three areas were likely to progress to action and maintenance stages over the 24-month study than the no-intervention group.51

Oliveira et al.55 found that male college students in a university setting reporting higher consumption of fruits and vegetables were in the action and maintenance stages. This result supports that of Kristal et al.59 in which adults in the maintenance stage were more likely to make greater dietary changes than individuals in other stages. This study was a 2-year trial which examined how demographic and psychosocial factors (belief in diet, barriers to adopt a healthy diet, and SOC) at baseline predict changes in dietary habits, including reduced fat and increased fruit and vegetable intake. SOC for adopting a low-fat or high fruit and vegetable diet was assessed at baseline.

De Vet et al.56 found that self-efficacy predicted forward stage transition from precontemplation to contemplation, whereas low self-efficacy predicted relapse from action or maintenance in Dutch origin. This very brief study included participants from a volunteer Internet panel, primarily Dutch, to respond to food frequency questionnaires asking about their dietary choices in the previous week, with additional demographic questions, and additional items used to assess the respondents’ SOC. Other items in the questionnaire assessed decisional balance and self-efficacy. A second follow-up questionnaire was sent one week later.

In addition, Di Noia et al.57 found that an interactive intervention program that addressed the health benefits of a diet rich in fruits and vegetables could help individuals make a change to consume more fruits and vegetables by moving forward to the next stage of change among African American teenagers.

Nothwehr et al.60 investigated the behavioral strategy used across stage of change in the case of healthful eating, and also whether the stage of change at baseline predicts the one-year change in the absence of any intervention process in a group of adults men and women in two communities in Iowa. While the correlation between baseline stage of change and one-year changes, it was not statistically significant; on the other hand, the use of a range of behavioral strategies was strongly related to SOC for healthful eating.60

Hughes et al.69 examined the outcomes of two worksite health care programs for older workers (i.e., age>40 years). Participants were placed into three groups: the COACH group used Web-based risk assessments combined with personal coaching, the RealAge group used a Web-based risk assessment combined with behavior-specific modules, while the control group simply received printed health materials. Each group was assessed every six months for one year. The COACH group demonstrated significant increases in the amount of fruits and vegetables eaten as well as more physical activity at both the 6- and 12-month assessments, and at 12 months were getting significantly less energy from fat. The RealAge participants demonstrated reduced waist circumferences at both 6 and 12 months. In addition, the COACH participants actually used the intervention twice as much as the RealAge participants used their intervention, and the COACH participants demonstrated twice as many positive changes as the RealAge participants.

Need for the Study

The prevalence of overweight and obesity are rising in the United States.9 Worksite-wellness programs have demonstrated effectiveness in improving weight-related outcomes.15,25-31 Researchers have used TTM to promote changes in different dietary and health-related behavior, such as weight, diabetes, and diet modification (including reducing fat consumption and increasing healthy food intake).55?63 However, limited current research has used TTM to predict weight and body fat as part of the measured outcomes following a behavior intervention for an overweight and obese population.

TTM is a helpful tool to use in guiding interventions and predicting outcomes when change occurs in adapting to new behaviors.64 TTM suggests that individuals engaging in a new behavior move through a series of five stages of change: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.17 Di Noia and Prochaska65 conducted a systematic review and found TTM to be a useful tool to help understand the decision-making process involved in dietary behavioral changes in individuals. Identifying the factors that affect individuals’ change from one stage to another can be challenging; however, doing so is important, especially in assessing a change from the action to maintenance stages over extended periods of time.41

The interest in investigating these outcomes arises from the current prevalence of obesity and its complications, such as CVD and diabetes12. The proposed study will examine participants’ clinical risk factors, weight, and body fat, which are associated with obesity, in relation to the participants’ SOCs in eating behaviors. In a search of literature published over the past five years, the PI has not identified any studies that explored the relationship between SOC in terms of eating behavior and changes in clinical measurements, specifically focused on weight and body-fat percentage among overweight and obese populations in a worksite-wellness setting.

Conceptual Model

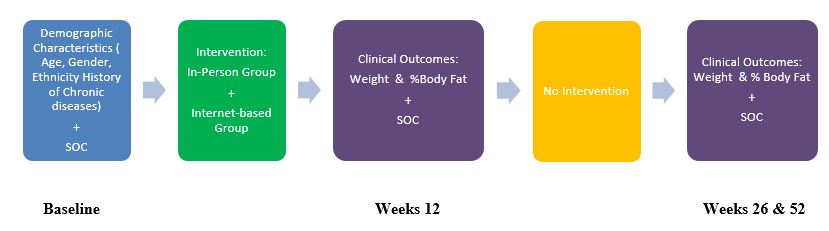

Figure 1 shows a conceptual model for the proposed secondary analysis. In the original study, the target population consisted of overweight and obese adults, 18 years of age and older, who were employees at the academic institution. In this model, demographic characteristics include participants’ age, gender, ethnicity, and history of chronic diseases. The independent variable or predictor variable is SOC in eating behavior. TTM is used to measure participants’ SOC regarding eating behavior at baseline and weeks 12, 26, and 52.

Study participants in the original study received the treatment through one of two methods: in-person (IP; Newark campus) or Internet-based (IB; Piscataway campus). Participants in the IP and IB groups received similar intervention information on healthy eating, physical activity, and behavior modification. The same registered dietitian conducted both arms of the 12-week intervention. The treatment groups were assigned to different campuses—the UMDNJ campuses at Newark and Piscataway—to avoid any potential contamination between the two groups. The selection of the study sites was based on convenience and space availability for baseline and follow-up assessments and group meetings as part of the worksite-wellness intervention. After completion of the 12-week education sessions, participants were followed at weeks 26 and 52 to obtain measurements. There was no intervention provided between weeks 12 and 26 and 26 and 52.

The dependent variables or outcome variables for this proposed research study are the clinical measures of weight and body-fat percentage. The outcome variables will be analyzed for changes across different time periods: from baseline to week 12, week 12 to week 26, week 26 to 52, and baseline to week 52.

The conceptual model applied to this proposed study describes how demographic characteristics and treatment intervention might have an impact on clinical health outcomes based on the application of TTM for the overweight and obese population enrolled in a worksite-wellness program. Determining which outcome measures are related to which stage in SOC will result in a better understanding of when and how much change can be gained. The PI in this research study will attempt to examine the predictive value of baseline SOC on weight and body fat percentage from one time point to the next. The results of this research study could lead to improvement or development of worksite-wellness programs to bring positive health effects to employees in worksite environments.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model

Methodology

Study Design and Sample Description

This proposed study is a secondary analysis of a closed data set from a 12-week worksite-wellness program conducted between 2006 and 2008 at UMDNJ through two different modes of delivery—in-person (IP; Newark campus) and Internet-based (IB; Piscataway campus)—with follow-up at weeks 26 and 52. All study participants were employees of UMDNJ’s Newark and Piscataway/New Brunswick campuses. The data collected in the original study18 regarding demographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity), self-reported co-morbidities, treatment characteristics, and clinical outcome measures of weight and body-fat percentage will be included in this proposed study.

The convenience sample included 137 adult men and women employees, aged 18 years and older, with a minimum BMI equal to and/or greater than 25.0 kg/m2. Sixty-nine participated in the IP group and 68 participated in the IB group. Participation in this study was completely voluntary. One hundred thirteen participants completed the 12-week intervention (82.5% completion rate), 96 participants continued through week 26 (70.1% completion rate), and 64 participants finished through week 52 (61.5% completion rate).

Study Methods

The primary purpose of this study is to explore the relationships between the SOC regarding eating behavior and changes in weight and body-fat percentage among the overweight and obese employees enrolled in the original study across four different time periods: baseline to week 12, weeks 12 to 26, weeks 26 to 52, and baseline to week 52. The PI will examine whether any of the clinical measurements are significantly associated with SOC. In addition, whether the SOC for eating behavior, as measured by TTM, predicts clinical outcome measures of weight and body-fat percentage at different time periods will be explored. The PI will receive a de-identified data set with relevant variables from the recorded data of the original worksite-wellness study conducted from 2006 to 2008. More details on the methodology of the original study can be found in the original study paper by Touger-Decker.15

Study Intervention

All participants received met with an RD for four individual sessions at baseline (week 1) and at weeks 6, 12, and 26 for data collection, counseling, and education. Individual sessions included a face-to-face interaction between an participant and the RD to establish an individual’s goals to meet his or her dietary needs and physical activity changes.18 Individualized tailored diets were designed to meet participants’ dietary patterns, food preferences, and energy needs for weight loss. Individual sessions also included assessments, counseling, education, and data collection on anthropometric and finger sticker blood glucose measurements as well as 24 hours diet recall. All participants who were provided 12 weekly face-to-face 50 minutes group sessions that focused on diet, physical activity, and chronic disease risk reduction. Group sessions also integrated education, questions and answers, weigh in, and interaction with an RD.

All measured were repeated at week 12 individual sessions. Diet and exercise guidelines were revised to reflect participants’ weight loss goals and changes in their health status. All measures were repeated along with discussing guidelines for diet and exercise for long-term weight management at the week 26 individual sessions. At week 52, participants were contacted to complete the study by repeating outcome measures.

Diet education information provided to participants was based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005, which is consistent with the recommendations from the AHA and the NHLBI DASH diet that focused on increased dietary fiber through fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and seeds; lowered total fat with less than 300 mg cholesterol; reduced sodium; and lowered fat protein and dairy to achieve and maintain a desirable body weight.66 The 12-week education intervention (Appendix A) highlighted the key topics of healthful eating, portion control, dining out, exercise, goal setting, and strategies for stress and food management. Participants were encouraged to exercise 30 minutes daily. A pedometer was given to each participant to record steps.

In the IP group, weekly group sessions were provided live for all participants for 12 consecutive weeks during lunchtime at the Newark campus. An educational session and discussion included such topics as healthy eating, physical activity, behavior modification, and challenges encountered by the participants. Participants were weighed weekly before each session started.

The participants in the IB group received the same sessions except that information and discussion was delivered online via WebCT.21 Educational materials given to the IP participants at weekly sessions were the same as those provided to IB participants. Participants came to their campus for a weigh-in once a week for 12 weeks. All participants received reminders via e-mail and telephone concerning their individual appointments. E-mail reminders were distributed to participants before the weekly sessions.

Assessment Questionnaire

The “Subject Data Sheet” (see Appendix B) was created for data collection in the original study.18 It included a demographic section that requested the participant’s name, height, baseline weight, ethnicity or race, gender, date of birth, and medical history. Data on the use of current medications were collected at baseline and weeks 6, 12, 26, and 52. The date and steps taken by the subjects as measured by pedometers were recorded in a table from week 1 to week 12 and at week 26 and week 52. The BIA was used to measure participants’ weight in pounds, calculated BMI, and body-fat percentage at baseline and weeks 12, 26, and 52. In the diet section of the “Subject Data Sheet,” subjects were asked whether a special diet was followed, how long the diet had been followed, and who instructed the subject to follow the special diet.

Healthy Eating Stage of Change Instrument

The use of the Healthy Eating Stage of Change instrument in the original study was based on the study by Hargreaves et al., 67 which assessed SOC regarding dietary fat intake. The instrument used to measure the healthy eating SOC was composed of five dichotomous questions to measure participants’ intentions concerning healthful eating.67 Participants were asked to identify their readiness to eat a healthy diet using a scale of 1?5. Each number reflected a healthy eating SOC based on TTM, with 1 indicating not ready to change or to plan to eat a healthy diet and 5 indicating a healthy diet is being followed and plan to maintain a healthy diet in the next 6 months.67

This self-reported SOC regarding healthy eating was obtained at baseline and weeks 12, 26, and 52. Participants will be classified into 5 stages derived from TTM to reflect their healthy-eating stages at each time point: baseline and weeks 12, 26, and 52. Table 5 shows the alignment between the SOC and participants’ indicated readiness to eat a healthy diet.

Participant’s Demographic and Treatment Characteristics

Age, gender, and ethnicity will be included as demographic variables. Age will be reported in years. Gender will be reported as male or female. Ethnicity will be reported as white, non-Hispanic or Hispanic; black, non-Hispanic or Hispanic; Asian or Pacific Islander, or Other. A self-reported history of chronic diseases will be categorized as the presence of one or more of the following co-morbidities: hypertension, dyslipidemia, CVD, type-2 diabetes mellitus, stroke, cancer, or arthritis.

Participation in the IP group or IB group will be included as treatment characteristic variables. Participants will be reported as being in either the IP or IB group.

Table 3. Stage of Change (SOC) Assignment*

| Stage of Change | Readiness to Make Healthy Eating Choices |

| Stage 1: Precontemplation | Subject does not eat a healthy diet and does not plan to change in the next 6 months. |

| Stage 2: Contemplation | Subject is talking about changing diet and plans to begin in the next 6 months. |

| Stage 3: Preparation | Subject is planning to make dietary changes in the next 30 days. |

| Stage 4: Action | Subject eats a healthy diet and made diet changes in the past 6 months |

| Stage 5: Maintenance | Subject eats a healthy diet and made changes more than 6 months previously. |

(* SOC Assignment is adapted from the original study by Hargreaves et al.,67 which classified subjects by SOC according to intention to change regarding fat intake.)

Clinical Outcome Variables

Weight and body-fat percentage will be included in this proposed study as clinical outcome measurements at baseline and weeks 12, 26, and 52. These clinical measurements for each point will be obtained from the original data. Table 6 summarizes the variables that will be used for analysis in this project. Both weight change and body fat percent change between baseline and each of 12, 26, and 52 weeks will be computed.

Table 4. Variables for Analysis.

| Variable | Specifics |

| Participant treatment group assignment | · In-person group

· Internet-based group |

| Demographics | · Age

· Gender · Ethnicity |

| Self-reported history of medical illnesses | · Hypertension

· Dyslipidemia · Cardiovascular disease · Type 2 diabetes · Stroke · Cancer · Arthritis |

| SOC in eating behavior | · Precontemplation at each time points: baseline, weeks 12, 26, 52, and each time periods: baseline to week 12, weeks 12-26, weeks 26-52, baseline to week 52

· Contemplation at each time points: baseline, weeks 12, 26, 52, and each time periods: baseline to week 12, weeks 12-26, weeks 26-52, baseline to week 52 · Preparation at each time points: baseline, weeks 12, 26, 52, and each time periods: baseline to week 12, weeks 12-26, weeks 26-52, baseline to week 52 · Action at each time points: baseline, weeks 12, 26, 52, and each time periods: baseline to week 12, weeks 12-26, weeks 26-52, baseline to week 52 · Maintenance at each time points: baseline, weeks 12, 26, 52, and each time periods: baseline to week 12, weeks 12-26, weeks 26-52, baseline to week 52. |

| Clinical outcome measures | · Weight at baseline to week 12, weeks 12-26, weeks 26-52, baseline to week 52.

· Body fat % at baseline to week 12, weeks 12-26, weeks 26-52, baseline to week 52. · Weight change from baseline to each of 12, 26, and 52 weeks. · Body fat % change from baseline to each of 12, 26, and 52 weeks. |

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria from the original study18 were male and female adults, 18 years of age or older, who have a BMI greater than or equal to 25 mg/m2. All participants who finished, at minimum, the 12-week intervention and those who returned to the follow up at weeks 26 and 52 will be included in the proposed study. For the purpose of the future program development, participants who did not return to weeks 26 and 52 for follow ups will also be included for the duration of their participation. Participants will be identified at what stage they dropped out from the program. Exclusion criteria included those persons who were less than 18 years of age, pregnant, or nursing within 3 months of the baseline.

Statistical Power

The original study had a convenience sample of 137 participants. A power calculation is not meaningful in this proposed study because it will use a closed data set for statistical analyses. Data analyses will be performed and set with a prior alpha level of p = .05. A post hoc power analysis will be conducted if results do not achieve statistical significance so that the PI can examine where non-significant findings were the results of type II errors.

Institutional Review Board Approval

The PI of this proposed study will apply for an exempt review before beginning this study. An application for this proposed study will be submitted to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of UMDNJ Newark Campus. This study will not begin until IRB approval is granted.

Study Procedures

The original data were entered into SPSS® version 16.0. The PI will use SPSS version 19.0 for statistical analyses. The PI of the original study will provide a de?identified data set with relevant variables to the PI of this proposed study. The PI will keep data on a password-protected computer. The variables to be used in analysis are shown in Table 6.

Participants will be assigned to the stage at four different time points: baseline, weeks 12, 26, and 52, for their eating behavior corresponding to the behavioral SOC based on TTM. Precontemplators will be designated as Stage 1, contemplators will be designated as Stage 2, preparers will be designated as Stage 3, actors will be designated as Stage 4, and those who are at maintenance will be designated as Stage 5.

Barriers and Limitations

One potential limitation of this study is the self-reported questionnaire on healthy eating behavior completed by the subjects. Therefore, the study may be susceptible to reporting bias. Additionally, the data collected from a convenience sample with voluntary participation in the study could have been provided by participants more motivated to make changes. The use of a self-selected sample from the university setting also limits the generalization of study findings. Another limitation of this study was the lack of a control group that received no intervention. Finally, missing data documentation may be a potential limitation of this study.

Statistical Analysis by Sub-problems

Sub-problems

Among overweight and obese employees enrolled in a 12-week worksite-wellness intervention program at an academic health sciences university:

Descriptive statistics will be used to analyze and report demographic and treatment characteristic data. Frequency distributions (n and %) will be used to analyze gender, ethnicity, history of medical illness, and group assignment (IP or IB). Descriptive statistics will be used to obtain the mean, minimum, maximum, and standard deviation for age in years. Potential outliers will be identified for age by using a scatter plot. Extreme outliers may be removed because they may artificially increase the value of a correlation coefficient or decrease the value of the statistics.

Descriptive statistics will be used to analyze data based on the SOC for each participant at each time point. Frequency distributions including n and percentage for each behavior stage at each time point will be obtained. The change in the proportion (percentage) of the sample within each SOC category will be compared descriptively from one time point to the next.

SOC will be identified at each time point including baseline, weeks 12, 26, and 52. Frequency distributions (n and percentage) will be used to identify and compare the category change in SOC over 2 time points (i.e., baseline–week 12). The 4 identified periods listed above will be measured and reported separately.

Descriptive statistics will be used to analyze and report the mean, minimum, maximum, and standard deviation for each time point for the variables of weight and body fat percentage. Potential outliers will be identified for weight and body-fat percentage by using a box plot.

A paired t test will be used to analyze the mean change in weight and body-fat percentage between time points. Four paired t tests will be conducted to examine the mean change of weight and body-fat percentage for the four time periods.

A general linear model (GLM) with repeated measure will be used to examine the effects of SOC regarding eating behavior in the changes of weight and body-fat percentage. Planed comparisons of repeated measures (repeated contrast and simple contrast) will be used to determine whether the measurements of weight and body fat percentage are influenced from one time point to another (baseline-week 12; weeks 12-26; weeks 26- 52; baseline-week 52) by the SOC stage. F statistics and significance will be reported. If significant relationships are detected between SOC and weight or body fat percentage, possible confounders (gender and age) will be entered in the models to determine whether gender or age act as confounders when determining the effects of SOC on weight and body fat.

Appendix A

Weekly Education Intervention Outline

| Week | Education Topics Outline |

| Week 1 | Healthful eating: What is a healthful diet?

Review of the program diet. |

| Week 2 | Portion control: portion sizing at home, away from home, in meals/snacks. |

| Week 3 | Exercise; making physical activity part of the daily routine. |

| Week 4 | Grab-and-go snacks; snack habits at work, at home, on the go |

| Week 5 | Supermarket tour |

| Week 6 | Exercise at your desk and other ways to sneak it in. |

| Week 7 | Getting the “D” word out of your vocabulary: Behavior change |

| Week 8 | Weight loss for the health of it: reducing risk for chronic diseases. |

| Week 9 | Restaurant eating: discussion of how to adjust your diet. |

| Week 10 | Stress and food: alternative strategies |

| Week 11 | New beginnings: keeping weight loss and exercise alive; setting new goals. |

| Week 12 | Overcoming recidivism; what to do when old habits creep in? |

References

World Health Organization. Controlling the global obesity epidemic. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/obesity/en/index.html. Accessed June 3, 2011.

Kopelman P. Health risks associated with overweight and obesity. Obes Rev. 2007;8(1S): S13-17.

Racette SB, Deusinger SS, Inman CL, et al. Worksite Opportunities for Wellness (WOW): effects on cardiovascular disease risk factors after a year. Prev Med. 2009; 49:108-114.

Ogden CL and Carroll MD. National Center for Health Statistics Health E-Stat. Prevalence of Overweight, Obese, and Extreme Obese Among adults: United States. Trends 1976-1980 through 2007-2008. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/hestat/obesity_adult_07_08/obesity_adult_07_08.pdf. Accessed Apr 28. 2011.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Obesity Trends. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/trends.html. Accessed Jan 20, 2011.

Centers for Disease control and Prevention. Press Release. Study estimated medical Cost of obesity. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/media/pressrel/2009/r090727.htm. Accessed Sept 27, 2009.

Thorpe KE. The Future Costs of Obesity: National and State Estimates of the Impact of Obesity on Direct Health Care Expenses. 2009. Available at www.americashealthrankings/2009/spotlight.aspx. Accessed Mar 13, 2011.

U.S department of Health and Human Services. Proposed Healthy People 2020 Objectives. Available at http://www.healthypeople.gov/. Accessed June 3, 2011.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vital Signs: State-Specific Obesity Prevalence Among Adults — United States, 2009. 2010; 59:1-5. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm59e0803.pdf.

Blosser F. Research Challenges in Work, Obesity, and Health Examined by NIOSH Scientists, Colleague in Journal Paper. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Assess Feb 10, 2011. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/updates/upd-04-11-07.html. Accessed Mar 13, 2011.

U.S department of Health and Human Services. Proposed Healthy People 2020 Objectives. Available at http://healthypeople.gov/hp2020/Objectives/TopicArea.aspx?id=35&TopicArea=Nutrition+and+Weight+Status. Accessed Oct 13, 2011.

Carnethon M, Whitsel LP, Franklin B, et al. Worksite Wellness Programs for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. A Policy Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009; 120:1725-1741.

Task Force on Community Preventive Services. A recommendation to Improve Employee Weight Status through Worksite Health Promotion Programs Targeting Nutrition, Physical Activity, or Both. Am Prev Med. 2009; 37:358-359.

Goetzel RZ, Gibson TB, Short ME, et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2010; 52 Suppl 1: S52-58.

Touger-Decker Riva, Denmakr R, Bruno M, O’Sullivan-Maillet J and Lasser N. Workplace Weight Loss Program; comparing Live and Internet Methods. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2010; 52:1112-1118.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcorss JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist 1992; 47:1102-1114.

Prochaska JO & DiClemente CC. Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Therapy, Research, and Practice. 1982; 19:276-288.

Touger-Decker R. Wellness in the UMDNJ workplace; lifestyle management program American Heart Association Clinically Applied Research Grant; 2008. Unpublished documentation.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Defining Overweight and Obesity. June 2010. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/defining.html. Accessed Mar 13, 2011.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Disease and Health Promotion. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm. Assessed Mar 13, 2011.

University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. Available at http://www.umdnj.edu/. Accessed Dec 22, 2010.

WebCt. Available at http://www.blackboard.com. Accessed Mar 13, 2011.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthier Worksite Initiative. http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/hwi/policy/policy101.htm. Accessed on May 6, 2011.

Verweij LM, Coffeng J, Van Mechelen W, Proper KI. Meta-analyses of workplace physical activity and dietary behavior interventions on weight outcomes. Obes Rev. 2010; 12:406-429.

Beresford SA et al. Worskite Study Promoting Activity and Changes in Eating (PACE): Design and Baseline Results. Obesity. 2007; 15: Supplement 1: 4S-15S.

Gemson D, Commisso R, Fuente J, Newan J and Benson S. Promoting Weight Loss and Blood Pressure Control at Work: Impact of an Education and Intervention Program. J Occup Environ Med. 2008; 50:272-281.

Haines DJ, Liz D, Rancour P, Robinson M, Neel-Wilson T, Wagner S. A Pilot Intervention to Promote walking and Welnness and to Improve the Health of College Faculty and Staff. Journal of American College Health. 2007; 55:219-225.

Milani RV and Lavie CJ. Impact of Worksite Wellness Intervention on Cardiac Risk Factors and One-Year Health Care Costs. Am J Cardiol. 2009; 104:1389-1392.

Racette SB , Susan S. Deusinger SS, Cindi L. Inman CL, Burlis TL, Highstein GR, Buskirk TD, Steger-May K and Peterson LR. Worksite Opportunities for Wellness (WOW): Effects on cardiovascular disease risk factors after 1 year. Preventive Medicine. 2009; 49:108-114.

Siegel JM , Prelip M, Erausquin JT, Kim SA. A Worksite Obesity Intervention: Results From a Group-Randomized Trial. American Public Health Association. 2010; 100: 237-233.

Terry PE, Seaverson EL, Grossmeier J, Anderso DR. Effectiveness of a workstie telephone-based weight management program. Am. J Health Promotion. 2011; 25:186-189.

Enwald HP and Huotari ML. Preventing the obesity epidemic by second generation tailored health communication: and interdisciplinary review. J Med Internet Res. 2010; 12 (2): e24.

Anderson LM, Quinn TA, Glanz K et al. The effectiveness of worksite nutrition and physical activity interventions for controlling employee overweight and obesity: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009; 37(4): 340-57.

Turner SL, Thomas AM, Wagner PJ, Moseley GC. A collaborative approach to wellness: diet, exercise, and education to impact behavior change. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2008; 20:339-344.

Cook RF, Billings DW, Hersch RK, Back AS, Hendrickson A. A Field Test of a Web-Based Workplace Health Promotion Program to Improve Dietary Practices, Reduce Stress, and Increase Physical Activity: Randomized Controlled Trail. J Med Internet Res. 2007; 9(2): e17.

Perez AP, Phillips MM, Cornell CE, Mays G, Adams B. Promoting dietary change among state health employees in Arkansas through a worksite wellness program: the Healthy Employee Lifestyle Program (HELP). Prev Chronic Dis. 2009; 6(4): A123.

Sternfeld B, Block C, Quesenberry CP, Block TJ, Husson G, Norris JC, Nelson M, Block G. Improving diet and physical activity with ALIVE: a worksite randomized trial. Am J Prev Med. 2009; 36(6): 475-483.

Spahn JM, Reeves RS, Keim KS, Laquatra I, Kellogg M, Jortberg B, Clark NA. State of the evidence regarding behavior change theories and strategies in nutrition counseling to facilitate health and food behavior change. JADA. 2010, 110(6): 879-891.

Palmeira AL et al. Predicting short term weight loss using four leading health behavior change theories. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2007. 4:14.

Andres A, Saldana C, and Gomez-Benio Juana. Establishing the Stages and Processes of Change for Weight Loss by Consensus of Experts. Obesity, 2009; 17:1717-1723.

Chae SM, Kwon I, Kim CJ, Jang J. Analysis of Weight Control in Korean Adolescents Using the Transtheoretical Model. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2010; 34(4): 511-529.

Holt DT, Helfrich CD, Hall CG, Weiner BJ. Are You Ready? How Health Professionals Can Comprehensively Conceptualize Readiness for Change. Society of General Internal Medicine. 2009; 25 (Suppl): 50-55.

Archie SM, Glodberg JO, Akhtar DN, et al. Psychotic disorders, eating habits, and physical activity: who is ready for lifestyle changes? Psychiatr Serv. 2007; 58:233-239.

Cahill, K, Lancaster T, Green N. Stage-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cocharane Database System. 2010. Nov 10; 11:CD004492.

Greene GW, Rossi SR, Reed GR, Willey C, Rochaska JO. Stages of change for reducing dietary fat to 30% of energy or less. JADA. 1994; 94:1105-1110.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997; 12(1):38–48.

Mochari-Greenberger H, Terry MB, Mosca L. Does Stage of Change Modify the Effectiveness of an Educational Intervention to Improve Diet among Family Members of Hospitalized Cardiovascular Disease Patients? JADA. 2010; 110 (7): 1027-1035.

Prochaska JO & DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983; 5:390-395.

Aveyeard P, Massey L, Parsons A, Mansaseki S, Griffin C. The effect of Transtheoretical Model based interventions on smoking cessation. Soc Sci Med. 2009; 68(3): 397-403.

Faghri PD, Omokaro C, Parker C, Nichols E, Gustavesen S, Blozie E. E-technology and Pedometer Walking Program to Increase Physical Activity at Work. J Primary Prevention. 2008; 29:73-91.

Johnson Sara et al. Transtheoretical Model-based Multiple Behavior Intervention for Weight Management: Effectiveness on a Population Basis. Prev Med. 2008; 46:238-246.

Kim CJ, Kim BT, and Choe SM. Application of the transtheoretical model: exercise behavior in Korean adults with metabolic syndrome. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010; 25 (4), 323-331.

Lippke S, Ziegelmann JP, Schwarzer R, Velicer WF. Validity of Stage Assessment in the Adoption and Maintenance of Physical Activity and Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. Health Psychology. 2009; 28 (2): 183-193.

Andres A, Gomez J, Saldana C. Challenges and applications of the transtheoretical model in patients with diabetes mellitus. Dis Manag Health Out. 2008; 16:31-46.

Oliveira Maria Do Carmo Fontes et al. Validation of a Tool to Measure Processes of Change for Fruit and Vegetable Consumption among Male College Students. J Nutrition Educ Behav. 2005; 37:2-11.

De Vet Emely et al. The Transtheoretical Model for fruit, vegetable, and fish consumption: association between intakes, stages of change and stage transition determinants. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2006; 3:13.

Di Noia J et al. Mediating variables in a transtheoretical model dietary intervention program. Health Education & behavioral. 2010; 37(5): 753-762.

Palmeria AL et al. Predicting short term weight loss using four leading health behavior change theories. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2007; 4: 14.

Kristal Alan et al. Predictors of self-initiated, healthful dietary change. JADA. 2001; 101:762-766.

Nothwehr Faryle et al. Stage of Change for Healthful Eating and Use of Behavioral Strategies. JADA. 2006; 106:1035-1041.

Intravais A, Sbrocco T, Hsiao CW, and Vaughn N. Decreasing stubbornness: how stage of change predicts readiness for change in weight management program. Annals of behavioral medicine. 2008; 35: S215.

Vallis M, et al. Stages of Change for Healthy Eating in Diabetes. Relation to demographic, eating-related, health care utilization, and psychosocial factors. Diabetes Care. 2003; 26:1468-1474.

Engbers LH, et al. The effects of a controlled worksite environmental intervention on determinants of dietary behavior and self-reported fruit, vegetable and fat intake. BMC Public Health. 2006; 17:253.

Tuah N, et al. Transtheoretical model for dietary and physical exercise modification in weight loss management for overweight and obese adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. Issue 4. CD008066.

Di NJ and Prochaska JO. Dietary stages of change and decisional balance: a meta-analytic review. Am J Health Behav. 2010; 34(5): 6118-632.

American Heart Association. Diet and Life Style Recommendations. Available at http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/NutritionCenter/HealthyDietGoals/Dictionary-of-Nutrition_UCM_305855_Article.jsp. Accessed June 3, 2011.

Hargreaves MK, Schlundt DG, Buchowski MS, Hardy RE, Rossi SR, Rosssi JS. Stages of change and the intake of dietary fat in African-American women: Improving stage assignment using the Eating Styles Questionnaire. JADA. 1999; 99:1392-1399.

DeJoy DM, Parker KM, Padilla HM, Wilson MG, Roemer EC, Goetzel RZ. Combining Environmental and Individual Weight Management Interventions in a Work Setting: Results From the Dow Chemical Study. JOEM. 2011; 53:245-252.

Hughes SL, Seymour RB, Campbell RT, Shaw JW, Fabiyi C, Sokas R. Comparison of Two Health-Promotion Programs for Older Workers. Am J Public Health. 2011; 101:883-890.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (23 Feb. 2011). Time use on an average work day for employed person ages 25-54 with children. Web. Retrieved from: http://www.bls.gov/tus/charts/chart1.pdf

Internet Usage Statistics (2011). World Internet Usage and Population Statistics. Web. Retrieved from: http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee