Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Thesis Paper Example

Abstract

More than two-thirds of the global population is likely to seek healthcare services from avenues other than the standard medical care available in hospitals. As much as the majority of these people probably self-treat themselves, the majority seek medical care from knowledgeable practitioners of traditional, indigenous systems of medicine. Some alternative caregivers include Ayurveda, Kampo, Native American Medicine, Traditional Chinese Medicine, Traditional Hawaiian Medicine, Unani, Latin American folk systems, etc. Despite the peoples’ various cultures, languages, geographic regions, world views, and health beliefs, these medical systems have several features. Including the use of integrated procedures, they frequently involve multiple botanical products, individualized diagnosis, and treatment of patients, an emphasis on disease prevention versus disease treatment, maximizing the body’s inherent healing ability and treating the ‘whole’ patient (physical, mental, and spiritual) rather than a single pathology.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) refers to therapeutic ideas, techniques, and therapies that are used in addition to or instead of conventional medicine (CAM). The number of persons seeking complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is rapidly rising. There are several causes for this shifting circumstance. This paper provides a framework of the issues surrounding CAM practices and the definition of Cam, and the uses of CAM. In addition, this paper examines the many taxonomies of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and offers an overview of CAM use in the United States. Furthermore, this research examines the existing activities of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in the health-care system.

This research identifies the most important professional and medical policy and practice problems related to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). It looks at the public knowledge of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), the techniques and tactics used in CAM-related theories, and how this information is used in practice. Lastly, the paper gave guidance to the research and practice societies as they make decisions and confront the obstacles of doing CAM research, translating research findings into practice, and dealing with the various policy and practice issues that emerge.

Introduction

Many people have shifted from standard hospitalized health care to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in the twenty-first century. According to studies, 42% of Americans have tried at least one complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapy. Despite the shift into CAM therapy, some medical professionals and physicians are against such treatment alternatives. As a result, about 40% of people who have used CAM therapy disclose the information to their physicians (HT et al., 2011). However, people looking for health care from CAM therapists exceeds the number of people looking for medical help from primary-care physicians.

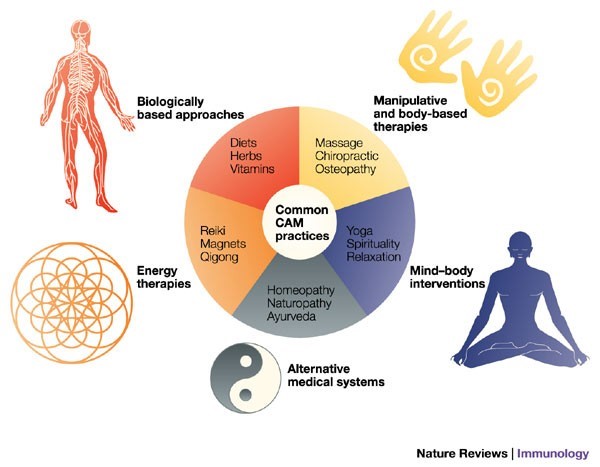

Additionally, gross income in CAM facilities is increasing, and as a result, the CAM business has grown significantly over the past decade. Therefore, professional health practitioners and healthcare facilities like hospitals and conventional care plants incorporate CAM therapies and practices into their profession (Piscitelli et al., 2000). Moreover, learning institutions that teach medical programs like medicine and nursing teach their students about CAM practices. Also, society has popularized CAM practices as they are published in newspapers and magazines and also the information is also popular in social media and the Internet (Goldrosen & Straus, 2004). The figure below shows some of the common CAM practice.

Figure 1.0

However, the question that has bothered most Americans who have not yet had a test of the CAM experience is if the CAM practices are safe. Most people would want to understand the concept of CAM and the effectiveness of the processes involved when one visits a CAM therapist. This paper essay analyses the issues surrounding CAM practices and the description of CAM, and its uses. Also, this study explores the various taxonomies of CAM and provides an overview of CAM use in the United States. Moreover, this study also provides current activities of CAM practices and the relevance of policymaking in the field of health care.

Background

Conventional medical professionals are being forced to investigate the efficacy and competence of health care in the United States as never before, which raises questions about the shift to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Strong evidence supports the underutilization of effective treatment, the overutilization of moderately effective or poor care, and the excess of care in its delivery, including unnecessary mistakes, according to the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) on their study “Crossing the Quality Chasm” (IOM, 2001). The fact that surgery rates and other therapies for common illnesses vary widely in populations in different places brings up questions on how physicians and patients make decisions.

Fragmented, gradual change, according to the study Crossing the Quality Chasm, will be inadequate to achieve sustained levels of standard development in American health care. According to the report’s 10 redesign rules, a fundamental redesign will be required. (Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s In a Name? | NCCIH, 2018). These proposals, taken combined, advocate for a systems-based approach to improving health care by making it more information-based and patient-centered.

The focus of this study is on complementary and alternative medicine, not on the value or delivery of mainstream treatment. Nevertheless, as will be seen, the leading element of the complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) idea is that its constituent components are “in addition to” traditional medicine. As a result, it’s critical to grasp both the benefits and limits of conventional medicine, especially as experienced by CAM users in America.

“What do patients and medical practitioners ought to learn to make successful choices about the use of medical care treatments, including complementary and alternative medicine?” is the starting point for framing this article. The research needed to support choices, policies, and resources to guarantee service quality, efficiency, and equal access is a corollary question for policymakers (Groft, 2001). Stakeholders in the American health-care economy has similar decision-making requirements for conventional and complementary and alternative health-care services. This is mirrored in the question’s broader scope and corollaries, which focus on health-care intermediaries rather than CAM therapies alone.

For the victims with indications that decrease the value of life or create worries on the extent of life, replies to basic but compelling inquiries are compelling for decision-making. What is the exact situation? If I do not react, will the condition improve, or worsen, or remain constant? What are my remedy options and what are the advantages and drawbacks? What can you expect from your treatment session? How much and how long will I be able to benefit? Wha are my likelihood of being harmed? and what are my possibilities of sustaining injuries and for how long? Those who have good health and wish to remain the same by avoiding avoidable illness ask such questions. De la Fuente-Fernández et al. (2001) explained that the solutions to these questions originate from an expert knowledge-base that may or may not be backed up by deductive conclusions applicable to the individual patient’s circumstances. Choices and subsequent treatment are considered to be “knowledge-based” when such evidence exists and is appropriately marshaled and communicated.

Professional understanding of treatment alternatives and outcome probabilities isn’t enough to make good decisions. The same symptoms may irritate different patients in different ways. They may have distinct reactions to the treatment itself and varied expectations for the benefits or dangers, or both. Furthermore, regardless of how strong the data is, there is always uncertainty about individual patient results (Harolds, 2016). Risks that some people find acceptable may be objectionable to others. Patients’ readiness to make trade-offs between the good and the bad is dictated by timely and untimely timings. Treatment and preventive choices, as well as the care that follows, become “patient-centered” when particular patients’ opinions and preferences are solicited and honored.

It has been suggested that there are high rates of unjustified variance in medical practice due to problems in knowledge management. In some instances, the required research has not been completed. In some cases, professionals are unable to access it at the moment of decision-making. Evidence can also be misunderstood or misapplied by a patient who is not the same as those who created the evidence’s foundation. Also, different health providers have disparate ideas on how a profession develops and grows its knowledge base. These epistemic gaps could be more evident among consumers who get conventional and complementary and alternative medical therapies.

In the last decades, traditional medicine practitioners have seen a shift away from relying on professional knowledge and toward a greater dependance on more rigorous quantitative data derived from randomized trials and systematic reviews of many studies. In CAM research, these more demanding approaches have just recently been used. However, among the diverse interventions that make up complementary and alternative medicine, there are different hindrances to using the trajectories that have become dominant in trying and improving the data base for traditional medical physicians, particularly those that depend on different practitioner interventions and the adoption of these solutions by individual patients.

Despite the obvious variances between conventional clinical practice and complementary and alternative medicine, perhaps the most promising way to find common ground is to ask, “What kind of knowledge do people need to make good health care decisions, and how can that knowledge be continuously tested and improved?”. This issue provides as a starting point for thinking about clinical and policy responses to the general public’s widespread use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States.

Methodology

For the report’s body, the researchers looked at a wide range of research on the use of complementary and alternative medicine in clinical populations that had been published in peer-reviewed journals. The research was derived from a PubMed search covering the previous eight years and any study reviews on CAM usage for particular health issues and unique populations. The study didn’t quantify the results because they were collected in diverse clinical settings using different data gathering techniques. If it seemed that CAM usage was prevalent in these locations, it was mentioned as such, or it was cited as illustrative. Much of the material of the research is based on a critical evaluation of epidemiologic studies of CAM use in the general population in America that employed random, nationally representative samples and were published in peer-reviewed medical journals.

Some of the article search included; a search of important social science articles encompassing the disciplines of anthropology, sociology, psychology, and geography, and a library search of CAM publications and book chapters published by individuals with advanced degrees and academic positions in renowned U.S., Canadian, Australian, and British institutions was used to produce articles for qualitative report comments and those about specific populations. The study’s data on various reasons for utilizing CAM was qualitative. A PubMed search yielded data on the absence of CAM compliance and adherence research.

The Concept of CAM

Determining what is added in the explanation of CAM is one of the most difficult elements of any CAM study. Is complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) inclusive of the use of vitamins, nutrition, and diets, as well as behavioral medicine, exercise, and other medication that are part of conventional systems? Should CAM include prayer, shamanism, or other therapies that aren’t recognized as medical treatments? Relaxation techniques, botanicals, chiropractic, and massage therapy are some of the most often used and well-known complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) remedies in America (Eisenberg et al., 1998). Chiropractors, acupuncturists, and massage therapists are all required to be licensed in most jurisdictions. Naturopathy and homeopathy are licensed in just a few states. Many other therapies and modalities are deemed unlicensed activities, and there are little or no legal guidelines in place for them at the moment. The New York State Office of Regulatory Reform has acknowledged more than 100 remedies, practices, and policies that might be categorized as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).

There is a lack of consistency in the definition of what constitutes complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) throughout the literature. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) of the National Institutes of Health defines complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) as a collection of medical and healthcare systems, practices, and products that are currently not considered part of mainstream medicine (NCCAM, 2002). Many would argue, however, that just because a therapy has been proved safe and effective and is used in mainstream practice does not imply it is no longer a complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapy (Shu et al., 2021).”Just because a physician uses a herbal cure does not mean that herbalists stop practicing or that one’s profession becomes the same as the other’s” (Hufford, 2002).

According to Ernst et al., complementary and Alternative medicine is defined as “a diagnostic, treatment, or preventative that adds to a common whole, meets a demand not met by orthodox, or diversifies the conceptual framework of medicine” (1995). CAM can also be defined as the Practices that are not regarded as right, suitable, or acceptable, or that are not in in line with the standards of the paramount group of physicians in society (Gevitz, 1988). Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) was defined by Eisenberg et al. in 1993 as therapies that are neither frequently taught in medical schools nor readily available in hospitals.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) definitions such as those provided by Ernst et al. and Gevitz, according to Kopelman (2002), do not sufficiently address the question, “What is CAM?” Definitions that exclude complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) from the politically dominant healthcare system fall short “provide a criterion for distinguishing conventional treatments from complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) that isn’t based on what is or isn’t fundamental to the dominant culture. This suggests that there is a mechanism for counting cultures or subcultures and categorizing them into dominant and non-dominant groups that is both accurate and helpful “(Kopelman, 2002). Other descriptive definitions fall short due to the fact that conditions change, resulting in incorrect portrayals of the situations. Consider Eisenberg and colleagues’ (1993) definition of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), which indicates that it comprises therapies that aren’t taught in medical schools and aren’t generally available in hospitals. However, more than half of all medical schools in America provide CAM courses, health care facilities provide CAM activities, and the sum of insurers that reimburse for CAM is increasing.

Normative criteria (e.g., untested or unscientific) also fail to distinguish CAM from traditional treatment, according to Kopelman. “There is only one drug that has been extensively tried, and there is only one medicine that hasn’t,” Angell and Kassier contend (1998). However, because many conservative treatments have not been well researched, such a definition does not distinguish between mainstream medicine and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). For example, an analysis of 160 Cochrane systematic reviews examining the effectiveness of conventional biological therapy found that 20% had no effect and another 21% had insufficient evidence (Ezzo et al., 2001). According to the study, some CAM makers use greater standards than are presently needed in the United States and test their CAM products thoroughly (Kopelman, 2002).

According to Kopelman, stipulative definitions (i.e., treatment lists) fail to distinguish CAM from conventional therapies since they vary from source to source and do not explain the exclusion of therapies that are not included.

Based on the lack of a clear description of CAM, a number of people have proposed classification schemes to help establish the field. NCCAM classified the CAM practices into five categories which are recognized globally in the health care system. These categories include; mind-body interventions, biologically-based treatments, manipulative and body-based methods, energy therapies, and alternative medical systems.

| CAM Categories | CAM Practices |

| Mind-body Interventions | Cognitive-behavioral approaches, meditation, hypnosis, dance, music, art therapy, prayer, mental healing |

| Biological-based treatments | Dietary supplements, herbs, orthomolecular (vitamins), |

| Manipulative and body-based techniques | Chiropractic, osteopathic manipulation, massage |

| Energy therapies | Qi gong, Reiki therapeutic touch |

| Alternative Medical Systems | Ayurveda, Acupuncture, Homeopathy, Naturopathy. |

Table 1.0

Alternative medical systems, as the name implies, are a large category that includes more than a single modality but a complex system of thinking and practice that developed independently of orthodox medicine. These practices include conventional Chinese herbs, ayurvedic therapies, homoeopathy, and naturopathy (Meeker and Haldeman, 2002). Secondly, Mind-body solutions, which include reflection, spiritual nourishment, and psychological therapeutic centered on the human mind but have an impact on the human body and physical health, are the second group in the NCCAM cataloguing system.

The third kind of treatment is biologically based, which includes specific diets, herbal products, and other ordinary commodities such as minerals, hormones, and biologicals. Specific diets include those promoted by doctors such as Atkins and Ornish, and the wider field of useful foods that may mitigate the dangers of disease or enhance health (Meeker and Haldeman, 2002). St. John’s wort and Ginkgo biloba are two well-known herbals that have been shown to help with mild to moderate depression and mild cognitive impairment. Fish oil is an example of a non-herbal natural material used to treat cardiovascular issues.

The fourth group, manipulative and body-based methods, includes therapies that entails movement of the body. Chiropractic is the famous in this group, and chiropractors are licensed to practice in every state in the US. A significant element of chiropractic medicine is the use of spine manipulation, alternatively referred to as spinal adjustment is used to treat spinal joint problems (Meeker and Haldeman, 2002). Reflexology therapy is also a form of body-based treatment. The last category defined by NCCAM is energy treatments, which include the application of energy fields to the body (Angell and Kassirer, 1998). Energy fields, and electromagnetic fields outside the body, are considered to exist inside the body. Although the presence of these biofields is yet to be experimentally proved, they may be found in various therapies such as qi gong, Reiki, and the healing arts.

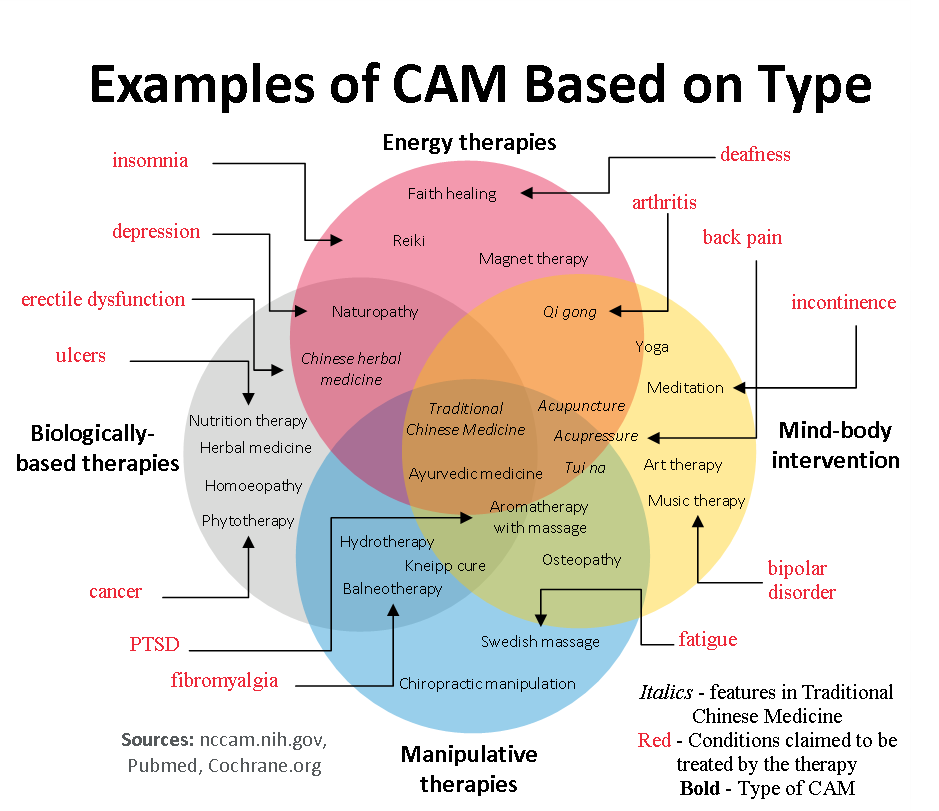

A detailed classification is a way of identifying CAM sense modality that classifies treatments from their scholarly ideas and applications (Kaptchuk and Eisenberg, 2001). There are two kinds of practices. The first type, known as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), is aimed at the general public. Professionalized or alternative medical systems (e.g., chiropractic, acupuncture, homeopathy), popular health changes (e.g., the use of dietary supplements and specialized diets), New Age medications (e.g., qi gong, Reiki, magnets), psychosomatic intercessions, and non-normative technical initiatives (traditional treatments deployed in modern ways or eccentric remedies employed by convents) are all found in this category (Angell and Kassirer, 1998). The second classification involves practices that are distinctive to certain ethnic or religious groups (for example, Native American traditional medicine, Puerto Rican spirits, folk medicine, and religious healing) (Goldrosen & Straus, 2004). Based on the aforementioned concepts, Figure 2.0 depicts an example of complementary and alternative medicine.

Figure 2.0

Although NCCAM’s recommended taxonomy is frequently used, this literature study indicates that there is no major definition of CAM, nor is there a familiar classification to structure the subject. The working definition will be based on a version of the language given by the Panel on Definition and Description at a 1995 NIH research methodological conference. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is now defined as a broad category of resources that encompasses health systems, modalities, and practices, as well as the associated concepts and beliefs, that aren’t now part of a country’s or culture’s mainstream health system. The phrase “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM) refers to resources that people feel can help them live a healthier life.

This term was chosen for many reasons in this investigation. First, this broad definition encompasses the scope and content of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) as it is perceived by the general public in the United States. Second, it ensures that common behaviors are not omitted from the research strategy. Because of the broad definition, not all of the reports and commendations in this research will apply to all CAM rules equally, and some CAM modalities may contain statements that do not apply at all. The third reason for choosing the above definition of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is because it is patient-centered and encompasses activities that people think are beneficial to their health. It also encompasses the possibility of change. This concept allows therapy to be approved as standard practice while yet retaining a complementary and alternative medicine component when there is confirmation of efficacy. Furthermore, the chosen definition acknowledges that the idea of “standard” medicine will evolve over time and between countries, and it does not imply that established treatments will be adopted.

Historical Overview of CAM

The American Congress formed the Office of Unconventional Therapies, later called it the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM), in 1992 to examine “unconventional medical practices.” A two-million-dollar budget was established, and OAM began collecting statistics on CAM use in the United States. Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Expanding Medical Horizons (Workshop on Alternative Medicine, 1995) was a 1995 publication that summarized the outcomes of two CAM workshops sponsored by OAM. The study (called the “Chantilly Report” after the workshops in Chantilly, Virginia, in 1992) examined six alternative medicine fields and addressed issues such as research infrastructure, databases, and methodologies. Many of the recommendations were made in response to research needs and opportunities. The research was notable since it was the result of the National Institutes of Health’s inaugural meeting on complementary and alternative medicine as a whole.

In response to public and business input, Congress passed the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) in 1994. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) established a definition for the term “dietary supplement” and demanded that complements be controlled like foods are. Because of this discrepancy, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) lost its premarketing regulatory authority, allowing manufacturers to skip premarketing safety and efficacy testing. The Research Centers Program was created by the National Institutes of Health in 1995 to focus on interdisciplinary CAM research at university institutions. Additionally, after a conference on the issue held by NIH and FDA in 1994, the FDA removed acupuncture from the classification for experimental purposes in 1995. The Public Information Clearinghouse on Complementary and Alternative Medicine was created by the National Institutes of Health in 1996. The Consensus Conference on Acupuncture was sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, and it offered proof of acupuncture’s efficacy for specific diseases (e.g., dental pain and nausea).

In 1997, OAM teamed together with the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Nutrition’s Office of Dietary Supplements to fund the first large-scale, multicenter study of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapy. Hypericum’s efficacy in treating depression was investigated in this study.

By 1998, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) had been thoroughly researched and hotly debated. “It’s past time for the scientific community to stop giving complementary and alternative medicine a free pass,” a New England Journal of Medicine editorial stated (Angell and Kassirer, 1998). Traditional and supplementary medicine cannot exist together Medication that has been adequately tested and medication that has not been adequately tested, medicine that works and medicine that may or may not work” are the only options. According to an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association, “There Is No Alternative Medicine.” There are two types of medicine: scientifically proved, evidence-based medicine based on solid facts, and unproven medicine based on no scientific proof. (Fontanarosa and Lundberg, 1998). In its complementary and alternative medicine themed publications, the American Medical Association published 80 papers including the results of 18 randomized trials. The findings of randomized controlled trials, editorials, descriptive studies, systematic reviews, and systematic reviews were all included. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) was treated as a complex topic for the first time. Journal editors were prepared to hold these works to the same editorial standards and scrutiny as works on traditional medicine concerns.

Meanwhile, after raising the OAM budget from $2 million to $19.5 million, Congress elevated OAM to the status of a state center known as NCCAM in 1998, granting it $48.9 million for fiscal year (F.Y.) 1999 and required NCCAM to nominate CAM practitioners as members of its Advisory Council. In 1999, the Cancer Advisory Panel for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) was formed to examine clinical evidence on CAM cancer treatments. NCCAM and the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Dietary Supplements collaborated to establish the first Dietary Supplements Research Center. Nine Centers for Research in Complementary and Alternative Medicine were financed by the National Institutes of Health to carry out transdisciplinary study and training. Three multicenter research studies were funded: one on Ginkgo biloba for dementia treatment (cofounded by NCCAM and the National Institute on Aging), one on glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate for knee osteoarthritis treatment (cofounded by NCCAM and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases), and one on acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis treatment. Large pharmaceutical firms also joined the complementary and alternative medicine industry in 1999, with herbal product lines and other dietary supplements.

In the years 2000 and 2001, several significant events happened. President Bill Clinton established the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy in March 2000. “Study and report on public policy problems in the rapidly developing field of complementary and alternative medicine,” the panel stated. The panel was also requested to submit “legislative and administrative recommendations to ensure that public policy promotes the advantages of suitable complementary and alternative medicine to Americans” (Executive Order 13147, 2000). The commission’s report recommended CAM research, education and training, CAM information distribution, CAM practice delivery, CAM coverage and payment, the potential role of CAM in wellness and health promotion, and the necessity for CAM-related initiatives to be coordinated (WHCCAMP, 2002).

In the year 2000, the Federation of State Medical Boards began developing CAM guidelines for physicians. The initiative was aimed at “encouraging the medical community to adopt consistent standards, ensuring public health and safety by facilitating the proper and effective use of both conventional and complementary and alternative treatments and ensuring public health and safety by facilitating the proper and effective use of both conventional and complementary and alternative treatments.” while training physicians on the necessary precautions to ensure that these treatments are given within the boundaries of professional practice” (FSMB, 2002). The guidelines were accepted by the House of Delegates of the Federation in April 2002.

The Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine was founded in 2000, with 22 medical schools as members by 2003. To join, the dean or chancellor must pledge to create CAM research, teaching, and clinical delivery programs, and the school must demonstrate a coordinated and comprehensive program in two of those three areas. The consortium’s mission is to “assist in the transformation of medicine and healthcare through rigorous scientific studies, new models of clinical care, and innovative educational programs that integrate biomedicine, human complexity, the inherent nature of healing, and the rich diversity of therapeutic systems.”

The only advantage gained from CAM therapies, according to skeptics, was due to a placebo effect, not “real” benefits. The Science of the Placebo: Toward an Interdisciplinary Research Agenda, held by the National Institutes of Health in November 2000, helped establish placebo as a “real” effect. An article on the basic scientific processes of placebo was published in the August 2001 edition of Science (de la Fuente-Fernandez et al., 2001). These two occurrences sparked a surge of interest among neuroscientists in studying nonspecific influences (such as anticipation, environment, and belief) on clinical outcomes. Placebo was no longer something to be laughed at or ignored but rather something to be taken seriously.

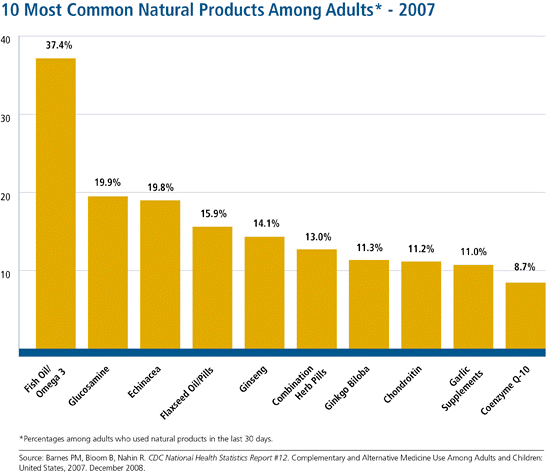

CAM on PubMed, free, web-based access to journal citations specifically linked to CAM, was also launched in 2001 by NCCAM and the National Library of Medicine. On the PubMed website, there are almost 40,000 citations on CAM at the moment (Phillips, 2007). In case studies (Fugh-Berman, 2000), clinically significant unfavorable drug-herb interactions were reported, and St. John’s wort was found to lower the amount of indinavir, a protease inhibitor taken by AIDS patients, in plasma (Piscitelli et al., 2000). The graph below shows ten of the most commonly used natural products among adults in the U.S. in 2007.

Figure 3.0

At the NIH Clinical Center, the world’s biggest institution dedicated to patient-oriented research, NCCAM began its Intramural Program in 2002 to investigate CAM therapy methods for patients. In the same year, the U.S. The Department of Veterans Affairs agreed to reimburse chiropractors. The Annals of Internal Medicine launched a special series on complementary and alternative medicine (17 articles), and Science Xpress published an article on positron emission spectrometry imaging of the placebo response versus the response to opioid analgesics.

NCCAM, whose funding had increased to $104.6 million in 2002, supported ten international planning grants, and more than 200 CAM-related research projects were continuing across the NIH. In the same year, the Institute of Medicine created the Committee on Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the General Public in the United States. The first two Centers of Excellence for Research on Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) were established in 2003 to improve the scientific rigor of CAM research. The NCCAM budget was $117.8 million in 2004.

Discussion

Policy Aspects

CAM practices have depended on individual financial support from the patients who seek such services. According to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) around 40% of adults and 12% of children seek CAM services (Alternative Medicine: Is It Covered? | U.S. News, 2016). Although, more people would seek CAM services if they were covered by insurance company and programs. programs like Medicare and Medicaid focus on insuring patience under the conversional medical care. CAM practices like chiropractic care, acupuncture and message therapy lack insurance cover and denies those people who can’t afford to pay for the services to enjoy these CAM medications. Therefore, policy consideration should be reviewed and people under institutional insurance support like Medicare and Medicaid should be able to get such CAM services at the lowest medical cost possible.

Medicare and Medicaid

Although both Medicare and Medicaid are government supported insurance program, they have differences on the people they cover. Medicare is a federal program that offers health coverage to people who are 65 years old and above and those who are below 65 years but have some form of disability (Differences between Medicare and Medicaid – Medicare Interactive, 2021). On the other hand, Medicaid is meant for people who below the minimum wedge or rather people who have very little income (Policy Basics: Introduction to Medicaid | Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2021). However, for those who have access to both insurance covers, have less to worry since their health expenses are reduced significantly. Unlike these federal health covers, some private insurance companies cover some of the CAM treatments but under certain conditions. Therefore, patients are forced to pay for most of their CAM treatments since most of the treatments are not covered by insurance companies.

Private Insurance Coverage on CAM

Statistical data from the NCCIH of a study in 2016 showed that more people are willing to pay for the CAM treatments out form their pockets. Moreover, between 2000 and 2012 people who Chiropractic care increased from 7.5% to 8.3%, for those who sought acupuncture care grew from 1.1% to 1.5% and those who sought message therapist rose from 5% to 6.9% (Alternative Medicine: Is It Covered? | U.S. News, 2016). however, some CAM treatments that are covered by insurance companies include Chiropractic which is covered by about 91% of big insurance companies. Others include Acupuncture, Massage, Homeopathy, Hypnosis, Biofeedback and Naturopathy. Nevertheless, most of these treatments are covered when conversional medical treatment has failed to show any sign of improvement on the patient. Therefore, most insurance companies decide to cover CAM treatments when there are special conditions.

Options For CAM Coverage

The NCCIH recommends that those who seek to have insurance cover on some of the CAM treatments should collaborate with their insurance health providers on the treatments they would with to be covered under. For example, some insurance companies provide different covers which cater for different health condition. Therefore, a patient should inquire if the services they choose cover some of the CAM treatments they would wish to be covered under (Alternative Medicine: Is It Covered? | U.S. News, 2016). Additionally, employees can also collaborate with their employers and be set on for a health benefit that covers them for CAM treatments (Alternative Medicine: Is It Covered? | U.S. News, 2016). For example, factory workers who operate heavy machinery can be enrolled to a monthly massage therapy to ensure that their physiology is healthy. These are some ways of how CAM practices can be covered. However more should be done on the policy formulations.

The federal government in association with private insurance companies should ensure that people are saved the cost of paying for CAM treatments. CAM practices have proven to be equally significant as conventional medicine and most people have recovered from conditions that conventional medicine had failed. Therefore, national health policies should be reviewed and more focus should be placed on CAM practices.

Current Activities of CAM

Findings are based on the CAM activities in various institutions.

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) supports continuing CAM-related research through twenty institutes and centers, with NCCAM serving as the principal center. The mission of NCCAM is to “conduct and support basic and applied research (intramural and extramural), research training, and [to] disseminate health information and other programs in accordance with recognizing, exploring, and authenticating balancing and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments, diagnostic and prevention modalities, disciplines, and systems.” NCCAM focuses on four key areas to fulfill its mission: research, research training, career management, community works, and incorporation. NCCAM establishes package significances through a semiannual formal review process to steer its research activities. Its three top priorities right now are elucidating mechanisms of action and conducting modest, well-designed Phase I and II trials; foster collaboration between institutions that provide conventional medical therapies and those that provide CAM therapies by building infrastructure to assist research at CAM institutions.

The most common technique for doing research is to establish research centers. There are various CAM-related research centers at NCCAM: Dietary Supplement Research, Developmental Centers that link institutions where CAM and conventional medicine are practiced, Centers of Excellence, CAM Research Centers, and Exploratory Program Grants for Frontier Research. The creation of worldwide centers for CAM research is also a project in the works. Unlike the other NIH centers, which spend roughly two-thirds of their research funds on fundamental research, NCCAM devotes most of its resources to clinical research; in F.Y. 2003, the ratio of clinical research spending to basic research funding was 2.5:1. (O’Brien, 2004).

Many patients are enrolled in NCCAM-sponsored clinical studies (10,708 in 2002), with more than half of them enrolled in Phase III trials. NCCAM focuses on prevention research (e.g., research into dementia, prostate cancer, and myocardial infarction) and studies on women’s health (e.g., research into the effects of plant-based estrogens), research into reducing or eliminating health disparities, and research into age-related health.

NCCAM has significantly boosted funding for training, career, and curriculum awards since F.Y. 1999 and boosted support for research project grants and research centers (Straus, 2003). NCCAM’s aim of expanding the number of qualified CAM researchers by making prizes for CAM-related research available to pre-and postdoctoral students, CAM practitioners, conventional medical researchers and practitioners, and members of underrepresented populations in scientific research are compatible with this funding.

NCCAM is also involved in several outreach initiatives. It has several outlets for both the general public and the scientific community. The NCCAM website includes extensive explanations of the organization’s active operations, as well as fact sheets regarding complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), information on variables that influence treatment decisions, cost and payment issues, and safety alerts and advisories. NCCAM also produces a quarterly newsletter that contains information on the center’s new and current initiatives. NCCAM also utilizes talks, town meetings, and exhibitions at scientific events to raise public knowledge about complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and the center.

In addition, NCCAM has developed a clearinghouse for anyone seeking information about CAM, which is accessible via the Internet and telephone in both English and Spanish. The clearinghouse does not give medical advice, but it does spread scientifically sound information about complementary and alternative medicine. Publications in peer-reviewed scientific journals, the number of which is growing, and the creation of the CAM on PubMed part of the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE database are two further initiatives that help with outreach.

One of NCCAM’s declared objectives is to “integrate scientifically validated complementary and alternative medicine techniques into mainstream care.” NCCAM’s expenditures in research, research training, and growing outreach have all resulted in integration. NCCAM hopes to help integrate CAM into medical, dental, and nursing school curricula by publishing research findings, investigating ways to integrate evidence-based CAM practices into conventional medical practice, and supporting programs that develop models for CAM integration into medical, dental, and nursing school curricula.NCCAM offers a well-organized and remarkable series of events to improve the level of knowledge regarding complementary and alternative treatments and their application. Although NCCAM’s statutory concentration is on complementary and alternative medicine, other NIH centers and institutes have impressive portfolios of CAM therapy evaluations. In 1999, NCCAM formed the 40-member Trans-Agency CAM Coordinating Committee to encourage collaboration among the many institutes and government agencies participating in CAM research. Some of the activities of NIH institutes and centers are described in the following section.

NIH Institutes and Centers

Other than NCCAM, institutions, and centers invest millions of dollars in CAM-related activities. The NIH institutes and centers collaborate and perform research independently, allowing for a broad range of clinical and fundamental research activities. There is ongoing research on the safety and efficacy of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practices for disease treatment and prevention; approaches of therapies such as soy isoflavones and acupuncture; placebo effects; the role of spirituality in health; and animal studies of alternative Parkinson’s disease therapies.

Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine

The National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine (OCCAM) develops and coordinates CAM initiatives linked to cancer. In 1998, OCCAM was founded. The program’s efforts are split into three categories: research development and support, practice assessment, and communications.

The Research Development and Support Program supports research into complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment and CAM for cancer-related symptoms and CAM modalities that can help with conventional therapy side effects. A methodology working group on research on cancer symptom management through the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), the provision of competitive supplementary funds for NCI-designated cancer centers, and a workshop on how to write a grant to receive funding for research on cancer-related CAM modalities are just a few of the recent activities.

The Practice Assessment Program has two main goals: first, to evaluate possible therapies and determine if more study is needed, and second, to create a conversation between health practitioners and researchers regarding complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and cancer concerns. The Best-Case Series Program for cancer patients treated with complementary and alternative treatments is supported by the Practice Assessment. The Kelly-Gonzalez Regimen for pancreatic cancer and Steven Ayre’s insulin potentiation treatment are two examples of best-case series that have been accomplished.

Finally, the Communications Program creates and disseminates information on NCI initiatives and collects comments on CAM-related cancer research interests and challenges. OCCAM, like NCCAM, hosts conferences, seminars, and proficient boards to advance the quality and visibility of CAM-related cancer research.

Office of Dietary Supplements

The Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS) was created in 1995 in response to a congressional authorities and is part of the Office of the NIH Director (DSHEA, 1994). Its mission is to “strengthen knowledge and understanding of dietary supplements by evaluating scientific information, stimulating and supporting research, disseminating research results, and educating the public to foster an improved quality of life and health for the United States population.”

Unlike the NIH institutes and centers, ODS cannot finance investigator-initiated research directly. However, it achieves its purpose through financing research, organizing conferences, and distributing information in collaboration with NIH institutes and centers and government and commercial entities. ODS published its plan, which included five broad objectives in research, information dissemination, and teaching. The utilization of new technologies, cross-disciplinary investigations, investigator training and education, research translation, and creating a mechanism for frequent evaluation of ODS programs and activities received more attention.

ODS has recently made several initiatives to improve the quality of dietary supplement research. For example, ODS developed a program to improve analytical techniques and generate standard reference dietary supplement formulations and two public databases: the Computer Access to Research on Dietary Supplements database (CARDS) and the International Bibliographic Information (IBIDS). CARDS is a database that keeps track of federally sponsored dietary supplement research and is updated regularly. IBIDS offers access to dietary supplement bibliographic citations and abstracts from published, worldwide scientific research. Evidence-based review reports commissioned by AHRQ Evidence-Based Practice Centers through a partnership between ODS and NCCAM are another resource for the research community and the general public.

ODS sponsors six Centers for Dietary Supplement Research in collaboration with NCCAM, the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The centers focus on botanicals to categorize and describe these compounds, as well as assess their bioavailability and activities, evaluates their methods of action, conduct preclinical and clinical evaluations, establish training and career development, and assisting in the selection of botanicals for clinical trials.

Agency for Health Care Research and Quality

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is charged with sponsoring, conducting, and disseminating research to improve the quality and effectiveness of health care. AHRQ oversees Evidence-Based Practice Centers (EPCs), which have published evidence-based studies on the effectiveness and safety of a restricted number of dietary supplements other federal agencies have requested (Templeman et al., 2015). The EPCs’ reports are based on a systematic study of pertinent scientific data and are intended to differentiate the types and strengths of a large body of evidence.

Proposals for clinical subjects to be evaluated by an EPC are accepted via Federal Register announcements. Clinical issues must fulfill certain selection criteria, such as a high incidence, relevance to Medicare, Medicaid, or other federal healthcare programs, high cost, discussions about efficacy, and scientific data availability. AHRQ also sponsors investigator-initiated research and some of donations for CAM-related research and the evidence-based practice reports.

Recommendations on CAM Practices

Individuals seeking to make judgments concerning the safety, efficacy, and usage of various CAM treatments and modalities face several obstacles. The IOM was commissioned by NCCAM, 15 other NIH centers and institutes, and AHRQ to research CAM usage by the general population in America. The study’s purpose was to describe how the general public in America uses complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) remedies and provide a critical overview of the therapies in use, the populace that use them, and how they are delivered. Also, the study identified significant scientific, policy, and practice concerns with CAM research and the implementation of proven treatments into mainstream medical practice. Moreover, the study was also commissioned to develop theoretical approaches or frameworks to direct collective- and individual decision making as the CAM research and practice groups face the pros of conducting CAM research, translating research findings into practice, and addressing the distinct regulation and practice barriers that arise because of that translation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has been utilized to prevent and treat diseases for some time. Many studies have shown that acupuncture, massage, and yoga reduce pain and improve function. Non-traditional treatment techniques offer the potential to prevent disease, enhance the quality of life, and reduce medical costs. Being able to provide natural treatments in place of or in addition to their treatment plan can only benefit them.

However, CAM faces several problems in the future. One of the hurdles is the scarcity of efficacy studies in CAM. This is the most important. Since no new healthcare policies have been developed to allow Medicare/Medicaid and CAM services are covered by private insurance. Also, our health care providers would need to be educated on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities to feel comfortable discussing alternatives with their patients.

Healthcare reform in the United States is urgently required since billions of dollars are being spent while less than average treatment is being given. The government, insurance corporations, and pharmaceutical companies control the medical sector in the United States, making billions by keeping people sick. A tailored approach must be developed to care for the patient’s emotional, bodily, and spiritual wellbeing. The new plan should include new healthcare regulations that would allow Medicare and Medicaid to support complementary and alternative medicine. This is how the United States will transition from a disease management system to a wellness network.

References

Alternative Medicine: Is It Covered? | U.S. News. (2016). Retrieved July 19, 2021, from https://health.usnews.com/health-care/health-insurance/articles/alternative-medicine-health-insurance

Angell, M., & Kassirer, J. P. (1998). Alternative medicine—the risks of untested and unregulated remedies.

Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s In a Name? | NCCIH. (n.d.). Retrieved June 22, 2021, from https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name

De la Fuente-Fernández, R., Ruth, T. J., Sossi, V., Schulzer, M., Calne, D. B., & Stoessl, A. J. (2001). Expectation and dopamine release: mechanism of the placebo effect in Parkinson’s disease. Science, 293(5532), 1164-1166.

de la Fuente-Fernández, R., Ruth, T. J., Sossi, V., Schulzer, M., Calne, D. B., & Stoessl, A. J. (2001). Expectation and dopamine release: Mechanism of the placebo effect in Parkinson’s disease. Science, 293(5532), 1164–1166. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1060937

Differences between Medicare and Medicaid – Medicare Interactive. (2021). Retrieved July 19, 2021, from https://www.medicareinteractive.org/get-answers/medicare-basics/medicare-coverage-overview/differences-between-medicare-and-medicaid

DSHEA, (Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994). Public Law No. 103-417, 108 Stat. 4325, 21 U.S.C. ss. 301 et seq. 1994.

Eisenberg, D. M., Davis, R. B., Ettner, S. L., Appel, S., Wilkey, S., Van Rompay, M., & Kessler, R. C. (1998). Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. Jama, 280(18), 1569-1575.

Eisenberg, D. M., Kessler, R. C., Foster, C., Norlock, F. E., Calkins, D. R., & Delbanco, T. L. (1993). Unconventional medicine in the United States–prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. New England Journal of Medicine, 328(4), 246-252.

Ernst, E., Resch, K. L., Mills, S., Hill, R., Mitchell, A., Willoughby, M., & White, A. (1995). Complementary medicine—a definition. The British Journal of General Practice, 45(398), 506.

Ezzo, J., Bausell, B., Moerman, D. E., Berman, B., & Hadhazy, V. (2001). Reviewing the reviews. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 17(4), 457.

Fontanarosa, P. B., & Lundberg, G. D. (1998). Alternative medicine meets science. Jama, 280(18), 1618-1619.

Fugh-Berman, A. (2000). Herb-drug interactions. The Lancet, 355(9198), 134-138.

Gevitz, N. (1988). Other healers. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Goldrosen, M. H., & Straus, S. E. (2004). Complementary and alternative medicine: Assessing the evidence for immunological benefits. In Nature Reviews Immunology (Vol. 4, Issue 11, pp. 912–921). Nature Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1486

Gordon, J. S. (2004). The White House Commission on complementary and alternative medicine policy and the future of healthcare. Alternative therapies in health and medicine, 10(5), 20.

Groft, S. C. (2001). Interim progress report: White House Commission on complementary and alternative medicine policy. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 7(6), 703–713. https://doi.org/10.1089/10755530152755261

Harolds, J. A. (2016). Quality and safety in health care, Part VI: More on crossing the quality chasm. Clinical Nuclear Medicine, 41(1), 41–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0000000000001012

HT, D., R, L., & SE, S. (2011). Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Cancer: Prevention, Early Detection, Treatment and Recovery, 499–530. http://europepmc.org/books/NBK11796

Kaptchuk, T. J., & Eisenberg, D. M. (2001). Varieties of healing. 2: a taxonomy of unconventional healing practices. Annals of Internal Medicine, 135(3), 196-204.

Kopelman, L. M. (2004). What conditions justify risky nontherapeutic or “no benefit” pediatric studies: a sliding scale analysis. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 32(4), 749-758.

Meeker, W. C., & Haldeman, S. (2002). Chiropractic: a profession at the crossroads of mainstream and alternative medicine. Annals of internal medicine, 136(3), 216-227.

O’Brien, K. (2004). Complementary and alternative medicine: the move into mainstream health care. Clinical and Experimental Optometry, 87(2), 110-120.

O’Connor, B. B., Calabrese, C., Cardeña, E., Eisenberg, D. M., Fincher, J., Hufford, D. J., … & Zhang, X. (1997). Defining and describing complementary and alternative medicine. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 3(2), 49-57.

Phillips, A. L. (n.d.). LibGuides: Complementary and Alternative Medicine: History and Impact of CAM. Retrieved June 23, 2021, from https://guides.hmcpl.org/c.php?g=790434&p=5657432

Piscitelli, S. C., Burstein, A. H., Chaitt, D., Alfaro, R. M., & Falloon, J. (2000). Indinavir concentrations and St John’s wort. The Lancet, 355(9203), 547-548.

Policy Basics: Introduction to Medicaid | Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2021). Retrieved July 19, 2021, from https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/introduction-to-medicaid

Templeman, K., Robinson, A., & McKenna, L. (2015). Complementary medicines in medicine: Conceptualising terminology among Australian medical students using a constructivist grounded theory approach. Complementary therapies in clinical practice, 21(1), 33-41.

Weeks, J. (2013). Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine Opens Dialogue With Joint Commission on Standards for Nonpharmacological Treatment of Pain… plus more. Integrative Medicine, 12(5), 14.

Young, A. L., & Bass, I. S. (1995). The dietary supplement health and education act. Food & Drug LJ, 50, 285.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee