Key Account Management in Pharmaceutical Market, Research Paper Example

Introduction

Consumers of pharmaceutical companies come from different areas of the world and are likely primarily chosen based on needs and specific beliefs. This specific condition makes it easier for business operators to strongly make an indicative choice of whether or not the products shall be bought and what specific brands would actually be able to meet their needs. Given that the industry thrives in the capacity of knowing how the behaviour of consumers impact the buying attitude of the people, organizations under the said industry make it a point that they are able to keep only the best suppliers in the market. Through this they make a great impact on how the choices of the consumers directly define their capacity to earn profit from sales (e.g., Dorsch, Swanson, and Kelley 1998; Stump 1995). To be able to make sure that they get only the best, they form agreements on research and development that would actually make a definite turn on how the market accepts the products that are presented to them through the said industry (Cardozo, Shipp and Roering 1992).

As Kempeners and van der Hart (1999, p. 312) note, in relation to account management, organizational system and operation becomes a specific source of confidence especially in relation to setting the foundation of development intact; through this course, organizational structure becomes evidently helpful. Internal organizational structures often avert a coordinated account management, like when a client is served by different group of product teams or by notably autonomous local sales operations. Additionally, sales teams cannot provide all the needed services for the group of activities for complex customers; this process needs the involvement of other functional groups.

These developments have encouraged many suppliers to reconsider to find new solutions to manage their top customers and shape internal organizations to respond to these key customers more effectively. Homburg, Workman, and Jensen (2000) argue in a recent study that the increasing importance for KAM (Key Account Management), which is one of the utmost essential changes in marketing, organizational structure evidently increases the capacity of any organization to embrace progress as needed especially in industries like that of the pharmaceutical operations in the market.

KAM can be defined as a methodology adopted by supplying companies that are aiming to establish a partnership that would assure them of quality products and stable profit from the market that they are serving. Through the existence of a key account manager, the capacity of a company to get the best medicines and offer them to the market at a relatively good rate of pricing becomes highly evident hence allowing them to have a share of control on the market. In this case, it could be realized that KAM is the establishment of customer focus and a source of relationship marketing in B2B (Business-to-Business) markets. Overall, KAM offers critical opportunities and benefits for the profit improvement to both sides of the seller/buyer couple. Indeed, based from these definitions, it could be realized that KAM is an important approach to the development and maintenance of large accounts, especially in the mature market conditions found in many pharmaceutical and related businesses. To better define KAM and how it affects the overall operation of the pharmaceutical industries, this paper shall provide an overall conditional presentation of the different theories and applications that surround the said procedure.

The Origins of Key Account Management

Key account management serves as the central control of the operations especially in connection with the existing company allies in the industry. Connecting the values of the sellers and the suppliers, the key account managers see to it that the desire of both parties is given particular attention to. Being a member of the agreement, both sectors ought to be strongly noted in relation to how they value the connection that they share.

Notably, the buying sector also noted as the decision-making unit becomes the central actor in the system. (Webster and Wind 1972b) A number of researchers have studied structural and behavioural characteristics of DMUs in numerous product/market contexts (Grashof, Thomas 1976; Wind 1978; Johnston, Bonoma 1981; Hutt et al. 1985; McWilliams et al 1992). These studies were valuable because they pushed the consideration of political behavior and power allocations within buying organizations and concentrated largely on the composition/dynamics of the DMU. More importantly, they induced social science thinking among managers who had been rather slowly in their receptivity to “soft” methodologies so far. In this case, interaction between parties specifically implicate a sense of distinction on how the agreements would be solidified hence providing a constant flow of values between pharmaceutical companies and the distributors of the said product.

When it comes to marketing, the operation out to be balanced as well (Jackson 1985; Christopher 1991; McKenna 1992; Millman 1993; Payne 1995). This balance aims to create a sense of distinction on whether or not a particular product would survive the market’s challenge especially in relation to the changing attitude of the buyers, which is expected to have an impact on overall market perception. Relating situations on open resource systems (Ffeffer and Salencik 1978) and internal/external “stake- holders” (Mitroff 1983; Freeman 1984) the condition of marketing is further refined hence making an instant impact on the presentation of each product as desired by both the producers and the distributors alike. Christopher et al, for instance, claim that “relationships outside the organization depend on the quality of relationships within it” (144), making the important point that strategic aim and shared internal values become part of the product/services proposed. McKenna re-describes marketing as “building and sustaining customer and infrastructure relationships” (134) , going on to put forward that a company’s credibility relies on the relationships it forms. As expected, these and other recent writers (Spekman and Johnston 1986; Gummesson 1987; Prazier et al. 1988; Webster 1992), have called for relationships to become the unit of analysis in future empirical research.

KAM Relational Development Model

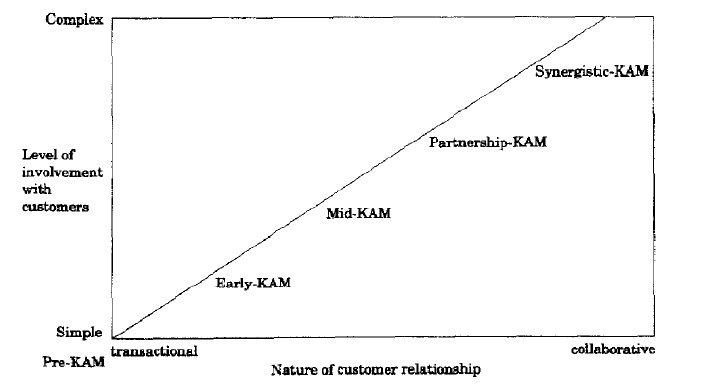

Key account management is an activity, which needs strategic thinking and a long term planning. The time needed to achieve the full potential of the relationship with the organization from identifying the account may take 10 years. It was obvious from the research that in supplying companies, which have a long history of key account management, account plans are prepared with the correctness required for marketing plans, using a parallel framework, and applying a minimum 3-5 year outlook. To note the procedural advancement of key management, Millman and Wilson’s model demonstrates the typical development of a relationship between buyer and seller by five phases — Pre-KAM, Early-KAM, Mid-KAM, Partnership-RAM and Synergistic-KAM. A sixth phase, Uncoupling-KAM, can happen at any time in the relational progression process. At this point, the diagram below shows a specific definition on how the process itself operates:

Figure 1 Key Account Relational Development Model (McDonald, M., Millman, T. and Rogers, B. (1997))

The volume of the business between the supplier and client and working relationships between the two companies can help to realize the model’s operation.

Pre-KAM phase: Where no business deal occurs, but a buying company has been targeted.

Early-KAM phase: Business deals have been occurred, but the supplier is still one of the many suppliers.

Mid-KAM phase: A supplier has reached a majority portion of the buying company’s buys and the buying company contact is expressing a preference for.

Partnership-KAM phase: Either a single sourcing relationship or something very similar, with the presence of a partnership performance indicator, or something close.

Synergistic-KAM phase: Single sourcing together with cross-boundary transactions delivery.

Pre-KAM defines preparation for KAM. In this phase, a buying company is defined as having key account potential, and the selling company starts to focus sources on creating some business with that vision. The Pre-KAM phase could be defined as a “scanning and attraction” phase. Both seller and buyer are transmitting signals (factual information) and exchanging messages (interactions) prior to the decision to engage in process.

At Early-KAM phase, the selling company is alarmed with defining the opportunities for account penetration once the account has been won. Tailor made solutions are needed, and in order to find these solutions the key account manager will be focused on understanding more about his/her customer and the market in which that customer is performing. The buying company will still be testing the other selling companies in the market, and expecting a presentation of value for money. The selling company must focus actively on product, service and intangibles — the buying company wants acceptance that the product offering is the prime reason for the relationship — and expects it to work.

At the Mid-KAM phase, the selling company has constituted reliability with the buying company. Connections between the two organizations grow at all levels and attain greater importance. But, buying companies still feel the need for other sources of supply options. This may be powered by their customers’ desire for choice. The selling company’s offer is still regularly tested in the market, but is reliably perceived as good value. The selling company is at that point a “preferred” supplier. There will be assumed continuity, even if individual agreements are renewed annually. There may still be exiting plans as well!

The priority shifts from product excellence to social integration at the Mid- KAM phase. Every person in the selling company will be expected to know the names of key accounts and know their importance to the company and the service that must be given. The buying company will at this phase know the people in the broad key account team as well, and some of the senior managers.

When Partnership-KAM is obtained, the selling company is considered by the buying company organization as a strategic external resource. Both companies will be sharing sensitive information and engaging in concerted problem resolution. Pricing will be long run and stable, possibly fixed, but it will have been established that both sides will allow each other to make a profit!

Synergistic-KAM is the last phase in the relational development model. Synergistic-KAM adverts to selling company and buying company together, creating value in the marketplace

Uncoupling-KAM defines the relational breakdown and highlights the need for contingency plans. Breakdowns can occur at any phase for various reasons, but the reason that occurred mostly was a breach of trust.

The Potential for a Collaborative Approach – the Product/Process Matrix

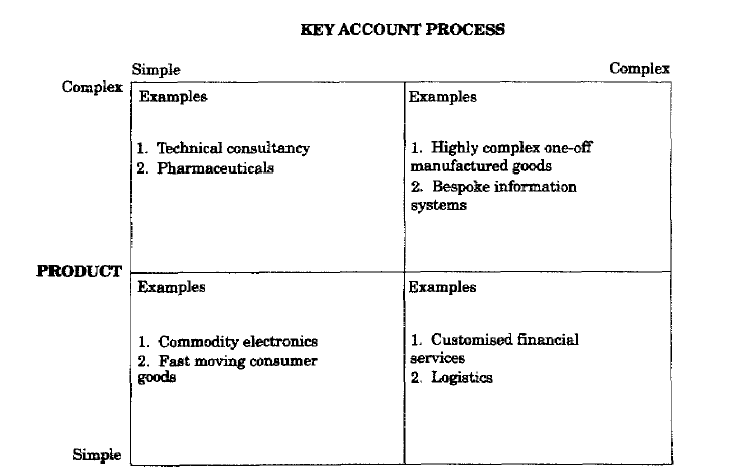

The correlative connection between the buyer and the supplier specifically insists on the capacity of the agreement to push forward for a mutual understanding between the parties involved in the process. In the diagram below identifying the product quality and the complexity of the process it undergoes in relation to production and banding is insisted to have a great role in the completion of a key account process.

Figure 2 The product/process matrix (McDonald, M., Millman, T. and Rogers, B. (1997))

Synergistic KAM depend fully on the complexity of the procedures taken into consideration by both the buyers and the suppliers. The complexity is often identified through the manipulation of the operations engaged in by both parties. As noted in the diagram above, the role of electronic factors being operated in the system gives an assurance for both parties regarding a perfect logistics that could assure on time deliver and high quality products at the same time.

In consideration with how the entire operation works, the formation of a key accounts management aims to identify what factors basically interact with the need of the organizations to push forward for a settled agreement. Scrutinizing how each party considers their role in the agreement forms a mutual connection that strengthens the value of the connection being formed.

The Selling Company’s Perspective — Identifying an Accounts as “Key”

Volume related factors. The volume of business coming in with a ratio of the 80/20 rule remains one of the most important considerations that is given attention to when forming a key account. With the capacity to measure the volume of business occurring along with the said account, the companies involved will have an overview of what they are likely to expect once the agreement already pushes through.

Profit Potential. Allocation of costs; understanding how much the agreement would mean for the business pursued by both companies, is what key management account sees through. Noting what account would be able to provide higher profit returns for both companies become a central condition of concern hence is expected to be fully considered by the parties involved in the agreement.

Status related. What status does a company have especially when it comes to defining its role against the role of the other company involved in the connection being formed. For instance, a supplying company may want to know which particular organization would ‘bid’ the highest when it comes to pricing the products it offers. On the other end, a buying company would of course want to consider the supplier that could give it a high quality product that could be reasonably priced for the sake of reselling the product in the market.

The attractive factor of a particular account affects the seller’s decision largely. Weighing their values of earning more from the market through their operations, selling companies tend to choose organizations that are likely able to give them a sense of ‘popularity’ in the market. Such familiarity that the end consumers will have on the brand they sell shall define a greater source of assured loyalty that would assure them of continuous growth both in the national and international scope of business.

The Perspective of Buying Company — Selecting Preferred or Partnership Suppliers

Ease of doing business: It is very important that the business be fully given regard especially in relation with the ease that it has in relation to the connection formed between the suppliers, the distributors and the end consumers of the product. For instance, the capacity of the business to make adjustments especially in connection with the changing perception of the market shall define the capacity of the partnership to become more capable of handling market changes effectively.

In this case, the companies involved should be able to understand the important aspects of the business that they should spend time with. Notably, the more time spent on less important things, the more time is wasted. Creating electronic programs to ease out the exchange of values between companies involved could better lessen the time and make the exchange of values easier to contend with.

Quality (product/service). The product/service package that the selling company offers create an assurance on the part of the buying company that they would be constantly given the best package available. The package mentioned ought to define the line between the business values and the consumer values that buying companies are aiming to balance in their operations.

Quality (people factors). The people in the selling company play a great role in defining the capacity of the agreement to be prolonged as desired by the parties involved. Relatively, the characteristic of the people such as honesty, loyalty and integrity define the possible connection that would be based upon trust between the selling and the buying company alike.

Skills Required in the Key Account Manager

Key account managers are expected to take on more responsibility than sales representatives do. Instead of just aiming to sell, key account managers are actually able to establish loyalty among the chosen buyers. Forming agreements with the buyers, key account managers establish accounts and specifically make a continuous connection between companies involved in the agreement.

Integrity. A majority of buying company contacts highlighted the importance of being able to trust the key account manager as an individual, in addition expecting selling companies to show corporate integrity. The importance of integrity to customers is either forgotten or taken for granted by selling companies, but buying companies stated how much they valued the conscious effort of suppliers to be trustworthy.

Product/service knowledge. Most of the buying companies expressed the opinion that it was very important for the key account manager to be able to handle technical questions and they also expected an in depth understanding of how the product or service could be applied. These fundamentals cannot be neglected.

Communications. KAM directors, key account managers and buying company contacts admitted the importance of fluency in speaking, presentation skills and exercising influence in meetings. Briefly, advanced interpersonal skills, were considered a “must”. Buying company contacts also mentioned “likeability”. Subjects of personal “chemistry” or “fit” were frequently brought up.

Understanding the buying company’s business and its environment. It would be difficult for a key account manager to be successful without a complete understanding of the buying company’s business. Knowing the industry in which the buying company operates is also required. Buying companies expected from the key account manager to know as much about the political, economic, social and technological factors affecting their business as they know themselves.

Selling/negotiating skills. Selling took up a small proportion of a key account manager’s time — it was as small as 10 percent of the key account manager’s activity in a mature seller/buyer relationship. Buying company contacts showed not much interest in the key account manager’s selling skills and were prone to expect key account management to be more sophisticated.

In the contrary, key account managers were well aware that they were paid for getting orders and said that a key account manager who forgets about selling is heading for trouble. Selling and negotiating were also considered highly valuable by KAM directors. One general manager leading key account managers said that they have to understand that their job is about making money and believed that those who fail as key account managers, while they might appreciate the money-making role philosophically, could not invest in it emotionally.

Customer relationship management in the pharmaceutical industry

It is commonly considered, within the industry at least, that the pharmaceutical marketing function is unique. The traditional marketing mix variables such as product life cycle, price, distribution and communication are investigated and firmly controlled by regulators and payers; and additionally, there are multiple customer groups to manage. The main pharmaceutical customer remains physicians, on the other hand patients, who are the end- users of the products, play a crucial role, as do insurers, governments and managed healthcare (MHC) organizations. Traditional pharmaceutical marketing strategy is based on the organization of large sales-forces. The sales-force model, the fountain of the industry, includes pharmaceutical sales representatives (reps) ‘detailing’ a portfolio of drugs to physicians. The sales-force is usually comprised as a matrix structure, where reps are part of territorial sales teams. This model proved entirely effective with the number of sales reps in the USA doubling over the 1990s and contributing to the double-digit annual sales expansion of the industry. Although the number of sales reps doubled, the annual rate of increase in the number of practicing physicians remained same over the same time period. In the USA, the annual 11 per cent increase in sales-force volume since 1993 has led to only a 2 per cent increase in physician visits. As a result, access to physicians has become increasingly difficult with multiple reps targeting the same doctors, thus heightening competition. A 2002 McKinsey study indicated that sales reps spend over a third of their time in the field providing samples at the physicians’ office, without in fact ‘detailing’ their products.

By the late 1990s, pharmaceutical companies encountered an ‘arms race’ in sales-force size and decreasing physician access, began seeking ways to increase return of investment in their sales-force by improving efficiency and effectiveness. The first wave of process improvement was implemented using electronic territory management (ETMS) systems designed to provide better arrangement of resources. The rational extension of this action was a move into CRM (Customer Relationship Management) technologies that targets collecting better customer data and to standardize approaches to the management of the interaction with physicians.

Hitherto, most CRM applications have intended to better manage the interaction with physicians. Companies have concentrated on leveraging CRM to improve the effectiveness of their operational marketing and sales activity to prescribers; in a sense using the CRM as a sales-force automation instrument. With the research concentrated on customer relationship establishment it is expected that CRM would define the obvious consideration on how the people would respond to a particular marketing approach as desired by the companies agreeing into a specific alliance for the sake of profit-defined goal.

Defining KAM in Pharmaceutical Industry

The changing situations of the pharmaceutical industry – maturing life cycles, consolidating customers, tense price pressures – should require for new approaches to managing customers. The characteristics of KAM, its various forms and how it differentiate from non-KAM sales management, applies broadly across most business-to-business contexts and is well studied. KAM application in pharmaceutical markets, however clearly business-to-business in nature, it differentiate from other business contexts in such aspects as market access, the role of clinicians, the implications of intellectual property protection and the nature of the value chain, as well as other factors.

The first step in KAM application and realizing its value in pharmaceutical markets is to define what it is that characterizes KAM and in what points it differs from routine account management of large customers. The key characteristics of KAM can be summarized in five points.

Key accounts produce more than financial value.

A basic difference between KAM and conventional approaches lies in the way value is defined. In KAM, the value key accounts produce is multi-dimensional, involving not only an exchange of money for product-related benefits, but also an exchange of non-financial value peculiarly in the form of knowledge or relationship assets. In pharmaceutical markets, this is mostly takes the form of jointly establishing new value propositions either product-focused (for instance, joint clinical trials) or service-focused (for instance, new working arrangements). Notably, this implies a move in the way that the value of an account is measured and managed.

Key accounts are key to both partners.

Peculiarly, a key account is specified thus simply because it is important to the supplier, but this is a one-sided way of looking at the relationship. A better and more effective definition is one that allows for the two-way value that KAM is aimed to generate. In deed key accounts that’s why, the partners who are important, or potentially important, to the other. This means that not only can the buyer present large potential sales and profit to the seller, but also the seller can present significant and usually distinctive value to the buyer. This means, of course, that the supplier has a considerably differentiated value proposition.

Key accounts have multiple relationships.

In conditions where traditional sales management mimics KAM, the vast majority of the relationship is established through the salesperson/buyer conduit. By doing so, however, is to fail to realize the key strength of KAM. In real KAM, most of the interaction between the two parties is diffused through multiple parallel contacts – technical to technical, logistics to logistics, commercial to commercial. In a pharmaceutical context, in which the salesperson may often need to call in support, it is easy to mislead conventional practice with KAM. The difference is found in the nature of the parallel relationships, which are ongoing and planned rather than temporary, and the role of the key account manager, as describer next.

Key account managers enable rather than sell.

A basic difference between conventional selling and KAM lies in what the key account manager does and does not do. The key account manager and main buyer, while producing final accountability, act as orchestrators of the relationship. To do so, this usually involves the key account manager being given authority particularly above that of a conventional salesperson, even if it is via a matrix, non-hierarchical structure. In the pharmaceutical context, this means that the conventional regional sales management structure is skipped, with the key account manager reporting in at national extent or even directly to a commercial director.

Key accounts have continuity.

As markets mature and pressure is brought to bear on the costs of non-differentiated products, a conventional approach is to introduce, by various names, sale by tender arrangements. These usually have time-related, particularly annual preparations to take advantage of downward price trends. The final annual horse-trading is, however, diametrically opposed to the principles behind KAM, which aim for a relationship-based approach to long-term mutual value. A real KAM approach tends to be much longer term, often a rolling arrangement with agreed exit procedures, thus reducing the time and cost of negotiating transactions. Good examples of KAM in pharmaceuticals often emphasize the value of this longer-term relationship by measuring and managing the long-term costs of managing a disease, something that itself requires a great deal of shared information and jointly developed strategies.

In contrast to traditional management of large accounts, therefore, key accounts are those that are able to provide not only a large volume of business, but also a partner in the development of new products or services and insight into?how the market as a whole works. In addition, purchasers will see a ‘key supplier’ as one who provides significant and distinctive value not simply through a highly differentiated product, but also through an extended service offer that improves the cost/benefit ratio of managing a clinical need. This is a long way from classifying all high volume customers as key accounts and illustrates the important differences between real KAM and its impersonators.

The Medical Science Liaison (MSL) Model

The MSL is a therapeutic area specialist (Oncology, Cardiology) in pharmaceutical, biotechnology, medical device companies who have advanced scientific education and generally “terminal D” degrees in the life sciences (Ph.D., Pharm D., M.D.). It’s crucial to highlight that MSL’s are not sales reps and their function is very different. The primary aim of the MSL position is to be scientific or disease state experts for internal customers (sales and marketing), but more importantly for physicians in the Therapeutic Area of the Medical community in which they work (Oncology, Cardiology). The point of the role has changed over the years, but the primal responsibility of the MSL role remains to develop and maintain peer-peer relationships with leading doctors, referred to as Key Opinion Leaders (KOL’s)

The position of the MSL was first established by Upjohn Pharmaceuticals in 1967 as a response to the need for professional field staff who would be able to build rapport with key opinion leaders (KOLs) in some areas of research and clinical practice. Upjohn coined the word “medical science liaisons”, but since then various names have been adopted, including medical liaisons, medical managers, regional scientific managers, clinical liaisons and scientific affairs managers. Pioneering structures, like many medical device and pharmaceutical firms, have created MSL (Medical Science Liaison) teams to support training, education, clinical initiatives, and research with their clients. Commonly, these MSLs use their scientific know-how to develop interactions and connections with and support the scholastic and investigational needs of clients within a definite geographical area. Generally these regions, because of the scare resources of head counts, are quite big, and with limited MSL assets, segmenting these customers is a must. As a result of this, MSLs use much of their effort and time working with a small group of customers called as KOL (Key Opinion Leaders) or Thought Leaders. KOLs; health-care providers who have quite good experience in their therapeutic area, have plenty of publications, and are usually still hands on efforts in on-going clinical trials. While these physicians mostly have influential power, even they are not the principle decision makers; they have an impact on decision-making groups or committees. For some companies forming appropriate strategies for success in cost cutting environment means laying-off large numbers of sales person, but for some other others such as Novartis, it translate to rearranging their sales teams to focus on key accounts instead of individual physicians; managed care and insurance carriers. Medical departments of companies must understand the environment and respond properly to both clients and firm’s necessities. MSL management should assess the aspirations of their company and recognise opportunities to increase the role of their team beyond the conventional focus on individual persons. If the MSL expands their client lists to include decision-making groups, they can help to energise the connection between the customer and the company, and boost their value to the organization.

Expanding the role of the MSL

For the last five years KAM approach has become more relevant to the business although it was not new. Existing market conditions that companies are opposing, like cost cutting and a reformation to more group decision making against the single physician method forced companies to do so. Many firms used KAM titles but not all of the companies gained the entire benefits trough KAM approach because they were not able to implement the concept effectively. Developing long-term relationships is the most important key performance indicator for success for a KAM. Then this means that companies should look to involve their MSLs, as one of the key players in KAM, creating relationships based on the scholastic, scientific and clinical needs of the customer

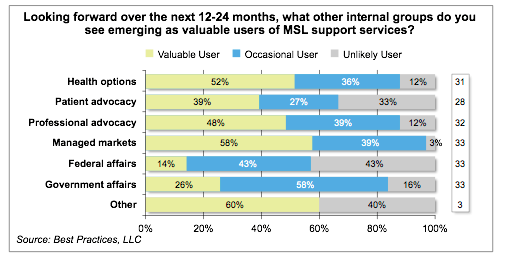

This innovative role of the MSL is reflected in a benchmarking study executed by Best Practices, LLC, which demonstrates (Table 1) the departments within a company that expect to utilize MSLs over the next few years. The study, including 33 executives from 30 biopharma companies in the US, conclude that MSLs provide a valuable service to health outcomes, managed markets, patient and professional advocacy and, to a lesser extent, government and federal affairs. Particularly, about 60 percent of responders believe managed care groups will be valuable users of MSL assistance over the next two years. Currently, 30 percent of companies constantly support internal payer groups. Evidence also propose one-third of companies are using emerging MSL trainer groups, such as patient/HCP trainers, scientific educators, health outcomes liaisons, or field-based physicians.

Table 1. Expected internal use of MSLs over the next 12 months (FirstWord Dossier (December 2011)

The question is how should a company look to extend the MSL function for being more supportive to KAM? Increasing the headcounts for MSLs may be a easy solution but without careful planning this may not ensure success.

Companies have answered this question in multiple ways.

- Some of the companies have developed an additional MSL team focused on specific key accounts, such as Managed Care. (10%)

- Some of them just added responsibilities and KPIs specific to key accounts to their conventional MSL team. (25%)

MSL executives will need to track the processes of understanding; detecting, planning, executing and finally evaluating in order to successfully integrate MSLs into KAM.

Understand

While an MSL executive decides to extend MSL role to more involve KAM support he/she must understand the firm’s position to KAM.

- Is it still traditionally sales minded or is it really a KAM positioning?

- What is the percentage of real KAMs in your customers?

- Are you choosing the right accounts?

- Do you have distinct knowledge assets?

- Are your KPIs right for measuring success?

- Are you designing new ways of and be open to double-loop learning?

If an organization does not understand these, and it is just reclassified sales management, then the concentration of the MSLs may be more adjusted to individual KOLs. There may be also opportunities for MSLs to find Key Accounts of their own, those that are critical for the success of the company, but that may not appear on the radar of their sales team. These could be professional medical organizations, guideline-developing groups or research cooperative teams.

Identify

After a director conceives what KAM means to their organization, and to their MSL team, they then need to determine what resources are available to support it. It is crucial to evaluate the team, both from a workload aspect as well as their skill sets. Generally, MSL teams are much smaller than the sales teams, and individuals take charge of large geographic regions. They may not have the room to add any other responsibility to their tasks. In addition to evaluating the capacity of the MSLs, do the existing team members have the skills needed to support key accounts? In most occasions, the scientific/clinical background of an MSL is the first characteristic looked at in hiring. In key accounts case, not only will an MSL need to be technically, clinically and scientifically capable, they will need marked business intelligence as well. MSLs ought to understand the key account’s business model, including all aspects, from financial to clinical, in the decision-making process.

Once the business requirement is understood, and MSL resources have been evaluated, the next step is to determine which method is most appropriate for the team. If key accounts have a relatively small percentage of the organization’s business, then an independent MSL team for KAM is probably not justified. If, however, key accounts are a main focus for the organization, and plenty of decisions are made by groups, then looking to establish a separate team may be appropriate. MSL Directors may also think through the development of dedicated teams that are not centralized around the customer, but rather the occupation of the group, like one team focused on clinical research, another focused on relationship development and a third focused on health outcomes. While this permits specialization of the individual MSL, it may bare some difficulties, as too many points of contact can be awkward to the customer, and it will add degrees of complexity to the internal communication.

Plan

The most crucial step in the expansion of MSL support to involve in key accounts is the development of a strategic plan that determines which accounts will be supported, what the total goals for the team will be, what objectives/metrics will be used to demonstrate success and what procedures need to be conducted for compliance. Working with the account management team is important as they will have business plans for single accounts, including background information on the decision-making process for each of them. MSLs can work with the account manager to conceive the individual accounts, assist with making charts of the key decision makers and then begin to establish specific activities for each account as well as which metrics will be used for measurement of MSL performances. Many of the activities that are generally done by MSLs are related to the key account audience as well. These include relationship development and liaising, presenting and discussing clinical data, supporting training program development, and including customers in clinical research. In parallel to the planning of activities and metrics for MSLs involved with KAM, MSL Directors will need to guarantee that they have developed operating procedures that describe the responsibilities of their teams and incorporate related regulatory guidance.

Relationship development and liaising: Relationship building with key accounts is a complicated process, and requires an extensive understanding of the organization, not only an individual. MSLs can support the account manager with mapping of the account’s key players, and developing and strengthening relationships. MSLs can also retrieve valuable information to their organization through discussions during calls, or more formal programs like ‘round table’ or ‘advisory board’ meetings with the key accounts. These discussions can take place even before the launch of a product, and are beneficial in determining reimbursement status, and identifying potential blockade and restrictions to use of the product.

Data-driven presentations: MSLs are familiar with giving data-driven presentations to their customers. In the conventional model, the information being shared has focused on therapeutic background and also clinical trial results. In the key account model, MSLs need to understand and be able to share additional information like health and pharmacoeconomic outcomes. Key accounts, such as Managed Care Organizations (MCO), utilize this information to change the choice for cost-efficient therapeutic alternatives. For that reason, pharmacoeconomic and outcomes data are becoming progressively important to MCO decision makers.

Trainin program development: While the involvement of pharmaceutical companies in the support of Continuing Medical Education (CME) programs is under inspection, there is still an opportunity to support the non-CME educational needs of customers. Actually, some MCOs have built partnerships with manufacturers to permit the company to access scientific support for programs and some manufacturers are providing inventive services including medication compliance programs and patient training programs.

Clinical research involvement: In generality of companies, a spesific part of the MSL role is to involve physicians in the development and conduct of clinical trials. These clinical trials, even larger, company or group sponsored trials, or smaller investigator sponsored trials, are designed to achieve additional clinical data and support for a product. Involvement in clinical trials should not be limited to specified physicians, but should include other physicians, like customers in the key accounts.

Actually, key accounts like MCOs have stated a desire to be involved earlier on and have their feedback anonymously into clinical development.

Regulatory considerations: However there are no peculiar regulatory references focused on the MSL role, there is guidance from the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that should be consolidated into the operating procedures MSLs involve. In 2003, the OIG issued a ‘Compliance Program Guidance for Pharmaceutical Manufacturers’, regarding peculiar risk areas that companies need to analyze, and the development of a code of conduct. Additionally, the FDA published updated guideline in January of 2009 regarding the distribution of journal articles and publications on not approved uses of drugs or medical devices. This document should be taken into consideration when developing procedures related to customer information requests and the use of scientific presentations. Given in the governmental guidance of the OIG and the FDA, other organizations like the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association (PhRMA) and Advanced Medical Technology Association (AdvaMed) have formed suggested guidelines for communications made with health-care professionals. While PhRMA and AdvaMed concentrate their recommendations on the commercial departments from a manufacturer, there are some areas that should be considered related to MSLs. Peculiar examples including working with consultants, speaker educating meetings, providing support for CME programs and working with health-care providers who are involved with formulary and decision-making groups. MSL Directors should develop guidelines for MSL function that follow the regulatory requirements of both the government and their own organizations and deliver training to their teams to ensure compliance.

Figure 3 below shows the complexity of today’s MSL and summarizes the principles described above. Circular movement is shown to highlight the interaction and flow between the MSL and different components between the sponsor and the medical healthcare society. In the model as you can see below, the MSL is in the innermost part creating dimensionality and depth which results in the dynamics and strength of the surrounding components. The core provides stability and the ability for movement and elasticity within the model as a continuum of the MSLs adaptability.

Ultimately, by scientific knowledge exchange, product market intelligence, and alliance with the healthcare community, research and development efforts are enhanced by the communication and MSL relationships which provide further tools and knowledge to the physician and enhanced patient care.

Implement

Once the planning phase is complete, and MSL resources are defined, it is time to implement the expanded focus. Not like some conventional MSL teams where communication with commercial peers is frowned upon, the sharing of related and important information in the key account procedure is crucial for success. With multiple relationships to manage, and complicated decision-making processes, cross-functional teams existed in an organization must focus on sharing information. Comprehensive communication plans should be established, and can include things such as monthly conference calls, quarterly meetings, located centrally business plans having access for everyone and face to face conversations. Additionally, organizations may assess the need for a tracking tool, such as Customer Relationship Management (CRM) software, which provide up-to-date customer information for all involved parties, and can streamline the communication process. While many companies may have tools already in use for their sales team, trying to adapt it to be used for KAM as well may put some legal/regulatory issues that should be discussed internally. There are some companies who are developing and advertising versions of their software designed specifically for KAM.

Evaluate

As is the case in any plan, it is crucial to track progress on goals and objectives and be able to assess the process as a whole. With a tool in use to track activities and relationships, MSL Directors should be able to deliver regular updates to senior management on their team’s role in supporting KAM. It is also important to look at the MSLs that are supporting the key account process, and assess whether you have sufficient support in both numbers and skill sets. If things are proceeding well, it may be used to support the proposition to increase the size of the team. If things are not going well, it enables the Director, and others involved with KAM to reevaluate their understanding, and make any necessary arrangements.

Metrics Demonstrating Success

Developing metrics that are proper and measurable for any MSL team can be a challenge. Most companies use a combination of qualitative and quantitative measurements so as to demonstrate the value of their team. Some quantitative examples seen in recent documents include the number of training programs developed, the number of presentations performed and the number of visits per customer within a certain time period. Qualitative examples are developed relationships with account/ customer, clinical trial involvement, advisory board involvement, cross-functional communication and information collected.

However many of these examples can be translated to the MSLs supporting the KAM role, there are some further metrics that should be analyzed. Evaluating how reactive an MSL is to the needs of the account, covering how many information requests have been received, and how quickly the MSL has been able to answer to these inquiries are quantitative metrics. Qualitative evaluations could also include taking feedback directly from customers, if possible, to show whether an MSL is adding value to the account, and how strong the relationship is between the MSL and various people within the account. In consequence of the goals and objectives of the MSLs who are involved with the KAM process, MSL Directors will need to assess which metrics are most suitable, and define a mechanism for obtaining and reporting on the results.

Looking at the process – Real life

Counting numbers

The numbers that everybody captures interest those things that MSLs generally execute: calls to KOLs, presentations, clinical trial support, medical marketing support, individuals on advisory boards, papers in medical journals, anything that raises the profile of their products.

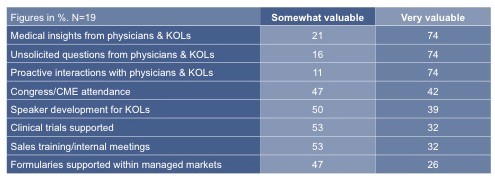

They do this by quantitative and qualitative measurement along the extensive lines used in the Best Practices study, Roles Resourcing and Management of MSLs. The results in Table 2 designate the kind of information that is typically captured as companies try to secure as full a picture as possible of what is their MSLs contribution to the company.

Table 2. Quantitative metrics rated by value (FirstWord Dossier (December 2011)

Qualitative metrics

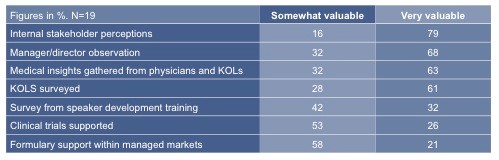

Numbers have limited value if they are not empowered with some kind of meaning. An MSL may have reach the frequency target but how can we assess did he or she perform well? Qualitative metrics are in this regard widespread. Table 3, using the same Best Practices data, demonstrates how the same pharmaceutical executives perceived the value of various commonly used qualitative metrics.

Table 3. Qualitative metrics rated by value (FirstWord Dossier (December 2011)

Qualitative measures are generally reported by MSL’s own, supported by feedback from managers and additionally internal and external customers.

How MSLs are deployed

As mentioned above companies are utilizing MSLs for many reasons. Their deployment is the subject of two US benchmarking studies carried out in 2010 by Best Practices. One of them includes interviews and benchmark performance data from 24 leading companies; the other from 33 companies. Taken into consideration together, they give some signs of the main trends in MSL placement in the US, which is typically ahead of Europe in terms of MSL practices.

The results verify that MSL workloads are increasing and, at the same time, diversifying:

- MSLs are getting more involved in IIT (Investigator Initiated Trial). Study shows a 10 % increase in MSL involvement in defining clinical trial sites in 2011 over 2009

- MSLs are increasingly identifying and communicating with patient societies. In 2011, 89 % of MSLs were involved in pre-lunch activities and 92 % post-launch activities. This is comparable with ratios of 58 % and 69 % respectively in 2009.

- MSLs are supposed to work more regularly with internal customers. Sales team and professional relations/ advocacy are the two groups served most frequently by MSLs: in 56 % and 44% of interviewed companies respectively.

- MSL involvement in defining and developing relationships with KOLs has increased by more than 20 % since 2009, in spite of a decrease in calls to develop relationships with KOLs. In 2009, there were approximately 14 calls per KOL and less than ten calls per KOL in 2011.

Current Situation in Turkey

At $11 billion, the drug market of Turkey is presently the 12th largest in the world, and in the last ten years it has doubled the volume. There are more than 300 drug firms in the market, of which 22.6% international and 77.4% are national companies. Drug expense per capita is low— $133 in 2010— when compared with $165 in Poland, $560 in Greece, and $956 in the USA. However, drug expenses represent 30% of all health expenses in Turkey compared with 10–15% in developed countries.

MSLs are sited under the organization of Medical Affairs Department and this model is quite recent in Turkey pharmaceutical practice. Medical affairs has the authority for all medical activities related to marketed products and also provides input to both clinical development and to commercialization. Within the medical affairs, the MSLs are the medical partners in the field for physicians and other healthcare stakeholders.

First MSL team was established by Novartis at 2005 in Turkey. In recent years the number of companies establishing MSL function are increasing in Turkey due to the additive value they brought to the business. Particularly small companies, who don’t have licensed products yet and can’t promote their products via sales force, inclined to establish MSL teams.

MSL is serving as the link between the physician and the sponsor in Turkey as well. MSL typically functions as the intermediary between the pharmaceutical company and the physician, serving roles in both the transmission of beneficial product information and the gathering of in-field medical information.

While rising numbers of MSLs are being hired to train researchers and clinicians about a company’s products they often find themselves walking a thin and contentious line when those products are known to be used off-label. Physicians want to talk about these uses and companies have an interest in sharing the recent scientific information, which can leave MSLs with the difficult question of how to apply the wide policy that don’t permit off-label promotion in almost every market in the world.

While there are strict codes of conduct for the company activities, there isn’t really specific guidance for MSLs or the MSL-type role. Because it is a relatively new position within the pharmaceutical industry, there is still lack of certainty on the proper non-promotional activities of MSLs. Companies in Turkey have to individually create their own guidelines on MSL activities, since there is great risk regarding compliance issues.

Although MSLs are allowed to talk to physicians about numerous disease indications, they are at increased risk in the following situations:

- The disease state or drug usage the MSL talks about is off-label for their company’s drug and a sales team goes into the office the same day.

- The MSL visits a physician to proactively talk about a drug that does not have indication for that area of medicine.

- The MSL goes to determined offices based on suggestions by the sales force.

At this point, companies need to determine what information can be exchanged, how it is reported and how the two separate faces of the company should communicate. Standard Operational Procedures (SOPs) can define how sales forces can induce an MSL visit to a doctor via a formal, fully recorded request system to medical affairs.

SOPs can also define how MSLs should return to requests for information or a visit, whether these come from sales force or medical affairs. It is not enough to just say off-label promotion is not allowed. The line between training and promotion can depend on the condition within which information is circulated.

Being clear is also needed when interacting with sales forces. Interaction with sales force would be totally legal if it were concerned only with training them about a drug or therapeutic area. If it also involved MSLs joining sales force on visits to doctors, organizing sales force visits on the same day an MSL has responded to a doctor’s questions on off-label usages, or MSLs visiting offices selected by the sales force, then the compliance factor for a company is clearly at risk.

SOPs for MSLs should reflect company procedure and its position on the following issues:

- How to interact with physicians, from both a medical affairs and a sales force perspective

- When an MSL can proactively contact a physician, and when contact should be reactive

- How to answer the requests for information on not approved drugs, including full recorded requests for information on not approved drugs

- Approval processes for materials to be shared by MSLs

- Proper interactions between medical affairs and sales and marketing teams

- How to handle the requests for research grants

- Reporting adverse events

- Speech for public

Conclusion

Key account management is a development of customer centricity and relationship marketing in business-to-business markets. It offers important advantages and opportunities for profit enhancement to both seller and buyer.

It is an important concept to the development and maintenance of large accounts, particularly in the mature market conditions found in many businesses. It seems that the dynamic conditions of the pharmaceutical industry – maturing life cycles, connected customers, intense price pressures – should search for new approaches to managing customers. Key account management, based on industrial marketing but linked with relationship and portfolio management ideas, is an approach that, for all its roots in very different sectors, has much to offer pharmaceutical marketers.

Medical Science Liaisons (MSLs) are a well-known function within the pharmaceutical industry. While in most organizations, MSLs have focused on the establishment of relationships with individual Key Opinion Leaders, growing companies have realized the value that MSLs can also bring to Key Account Management. MSLs are progressing into highly strategic function. Advancing organizations that can realign their MSL’s responsibilities and improve their scientific expertise with key accounts can expand on the success that has been demonstrated with individual physicians. Based on a needs evaluation of the company, MSL Directors can form a strategy for incorporating MSL support into the KAM process. In order to do this successfully, MSL Directors need to develop crystal clear activities and metrics for MSLs support for the needs of their organization, make sure that they have adequate resources attainable and are using qualified team members.

While rising numbers of MSLs are being hired in Turkey, companies should be aware of the potential risks of MSL role while interacting with physician and create related SOPs in order to avoid compliance issues they may face.

References

McDonald, M., Millman, T. and Rogers, B. (1997) Key account management: Theory, practice and challenges. Journal of Marketing Management 13(8): 737–757.

Christian Homburg, John P. Workman Jr., & Ove Jensen (2002), A Configurational Perspective on Key Account Management, Journal of Marketing Vol. 66 (April 2002), 38-60

Gagan Bhalla, Theodoros Evgeniou, Leonard Lerer (2004), Customer relationship management and networked healthcare in the pharmaceutical industry, International Journal of Medical Marketing Vol. 4, 4 370–379

Smith, B. (2009) Myth, reality and requirements in pharmaceutical key account management. Journal of Medical Marketing 9(2): 89–95.

Smith, B. (2009) Key account management: Always read the label. PharmExec, 17 August, http:// pharmexec.findpharma.com/pharmexec/Europe/ Key-Account-Management-always-read-the-label/ ArticleStandard/Article/detail/619399, accessed 25 August 2009.

David M. Shearer (2009), Medical Science Liaison: Emerging Roles, MD and Integrated Clinical Trial Services, LLC

Kientop (2009), Integrating Medical Science Liaisons into Key Account Management, Journal of Medical Marketing (2010) 10, 45–51

FirstWord Dossier (June 2011), MSL-KOL Engagement: Ensuring Compliance, A FirstWord ExpertViews Report

FirstWord Dossier (December 2011), MSL Metrics: Measuring Success, A FirstWord ExpertViews Report

Civaner M (2012), Sale strategies of pharmaceutical companies in a “pharmerging” country: The problems will not improve if the gaps remain, Health Policy Volume 106, Issue 3, August 2012, Pages 225–232

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee