Lateral Violence in Practice Settings, Capstone Project Example

Lateral Violence in Practice Settings: Risk Analysis and Best Practices in Nursing

Abstract

The proposal advances recent trends in organizational systems solutions for risk mitigation of lateral violence in healthcare institutions. Query to the proposal is focused primarily on the reporting on lateral violence by employees in clinical workplaces. The study of lateral violence (LV) has become increasingly important within the advancement of healthcare institutions as sites of patient care. Significant to the proposed research is the prevalence of violations of ‘duty to reasonable standard of care’ in this regard, and pertains to the broader issue within clinical settings today, which points to a high prevalence of nurse-on-nurse violence in that sector.

Studies in horizontal hostility are somewhat limited due to the nascent scholarly field of inquiry on the topic, and interpretation of methodologies within the proposal are based on the Stanly/Martin (2007) pilot study Applied Model of Oppressed Group Behavior to Explain Lateral Violence in Nursing. Hypothesis to the study is dedicated to assessment of the impact of oversight and training on mitigation of LV, and negation of those forces as a conduit for increase of misconduct.

The PICO(T) format to the study indicates: Patient Population – general; Intervention Issue – LV in practice settings; Comparison Intervention – convenience sample of nursing staff; Outcome of findings disseminated in report form for peer review; and Time of study one month.

Introduction

On October 27, 1969, Prosenjit Poddar killed Tatiana Tarasoff. The Plaintiffs, Tatiana’s parents, alleged that two months earlier Poddar confided his intention to kill Tatiana to Dr. Lawrence Moore, a psychologist employed by the Cowell Memorial Hospital at the University of California at Berkeley. They allege that on Moore’s request, the campus police briefly detained Poddar, but released him when he appeared rational. They further claim that Dr. Harvey Powelson, Moore’s superior, then directed that no further action be taken to detain Poddar. No one warned plaintiffs of Tatiana’s peril.

In Tarasoff v. The Regents of the University of California [S.F. No. 23042, Supreme Court of California, July 1, 1976], in a wrongful death action against the Regents of the University of California, psychotherapists at a university hospital, and campus policemen, by the Plaintiff, the victim’s parents whom attested that the Hospital staff had been informed in of the patient’s intention to kill their daughter. The trial court sustained defendants’ demurrers to the complaint without leave to amend and entered judgment in favor of defendants. The Supreme Court affirmed the judgment in favor of the police officers and reversed the judgment in favor of the therapists and the regents. The court held that plaintiffs could amend their complaints to state a cause of action against defendant therapists by asserting that they had in fact determined that the daughter’s killer presented a serious danger of violence to her, or pursuant to the standards of their profession should have so determined, but nevertheless failed to exercise reasonable care to protect her from that danger.

The court held that when a therapist determines, or pursuant to the standards of his profession should determine, that his patient presents a serious danger of violence to another, he incurs an obligation to use reasonable care to protect the intended victim against such danger. The court furthered that the decision whether to warn was not a discretionary act within the immunity provisions of Gov. Code, § 820.2, as judicially interpreted. As to plaintiffs’ claim of a breach of the therapists’ duty by reason of their failure to procure the killer’s confinement, however, the court held that they were insulated from liability by the provision of Gov. Code, § 856. Concerns in favor of nondisclosure (§ 5328), thereby promoting effective treatment, reducing temptation for overcommitment, and ensuring greater safety of society were central to judicial articulation in decision of the landmark case which indicates that healthcare organizations as defined in Healing Arts and Institutions § 30, ‘Medical Practitioners and Duty of Therapist to Dangerous Patient’s Intended Victim,’ determines that pursuant to the standards of the profession, that disclosure of serious danger of violence to another is an obligation to use reasonable care.

The foregoing proposal advances recent trends in best practices directed at risk mitigation of lateral violence in healthcare settings. Query to the proposal is focused primarily on the reporting on lateral violence by employees in clinical workplaces. Tarasoff v. The Regents of the University of California furthers this discussion in that the complexity of ethics in practice settings, and urgent care environments in particular, are subject to layers of ‘duty to reasonable standard of care’ within the law, as dangers presented by intentional non-disclosure or transmission of inaccurate information is interpreted as a form of ‘violence’ that may affect both patients and staff.

Problem statement

According to the Center for American Nurses (2008), the presence of lateral violence in healthcare organizations is extensive. The U.S. Federal Bureau of Labor and Statistics reports that nearly half of all nonfatal injuries in the workplace result from violent acts against co-workers in the healthcare sector, and in many if not most states, the healthcare sector ranks amongst the top five locations for incidents of workplace violence. Of those reporting, nurses, nurse’s aides and orderlies are predominantly the victims of those injuries (OSHA, 2004). Extensive documentation on the internal front reveals that incidence of disruptive and other anti-social behaviors by staff and superiors within the high demand context of clinical care institutions reveals exceptionally high levels of serious negative behavior, and attendant outcomes to misconduct issues.

At present, much attention to the range of misconduct problems experienced by clinical care staff, from malpractice litigation to bullying and sexual harassment, is allocated to directive interventions within policy legislation and attendant ethical recommendations. Dedicated to the development and dissemination of best practices for healthcare administration, policy institutions are instrumental in combating the seemingly epidemic level of abuse in the healthcare workplace. From the perspective of healthcare organizations, the standards of compliance and legal rule provisions for the management and conflict resolution of clinical care settings is particular in that employees are especially inclined to be under duress from a number of factors, and patient care is of preeminent importance whilst institutions face serious nursing shortages.

Legal matters responsive to rather high profile cases of complaint related to violent acts in the healthcare workplace, prompted widespread investigation toward mandate consideration of new regulatory restrictions by the Joint Commission, OSHA and NIOSH in 2001. By 2002, the Joint Commission had extended the direction of the recommendation to ratification of articles to address a range of violent perpetrations, and including mitigation against threats of physical assaults as terrorism as defined within U.S. Federal MPC (Modern Penal Code) statute. The American Association of Occupational Health Nurses (AAOHN) reinforced this statement in 2003, with public support of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) definition of workplace violence “any action that may threaten the safety of an employee, impact the employee’s physical or psychological well-being, or cause damage to company property.”

Due to structural position and intense levels of responsibility to patients in urgent or clinical care in practice settings, nurses are faced with multiple hazards that put them at risk for harm. An occupational problem for this segment of the medical workforce, nursing is targeted for multidimensional analysis that begins with individuals, but ultimately impacts the sustainability of a safe and ethical environment. Solutions to violence in healthcare organizations must come from a range of considerations that include both patient related risk and intentional negligence by colleagues. Change management practices in healthcare settings typically acknowledge the transitional nature of the nursing profession, as the job requires long endurance shifts, and the shortage of skilled practioneers promotes relocation frequently. Organizational capacity is reduced in response to the flexible demands of staffing; presenting a significant challenge to administrative oversight as the transitional engagement of nurses promotes prioritization of environmental control according to compliance and internal policy and little in regard to provision for protection of labor rights.

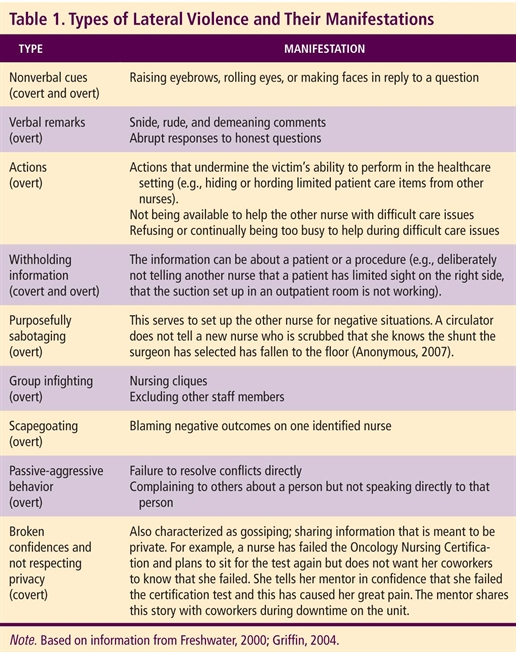

Exhaustion by nurses on the job is a standard complaint, and it is not surprising that reports on lateral violence, and especially horizontal grievance against other nurses contains violations pertaining to the intent to humiliate, infighting, make vulnerable, non-verbal innuendo, risk to safety, verbal affront, undermining activities, withholding job pertinent information, sabotage, and scapegoating (Griffith, 2004). Generally, and without exception, breach of privacy or failure to respect privacy of individuals is situated here, and is certainly the primary most detrimental misconduct problem often leading to a range of subsequent abuses. Figure 1 illustrates the variance in the current definition of ‘lateral violence’ as a formative issue in nursing practice (Griffin, 2004).

Figure 1

Figure 1: Types of Lateral Violence and their Manifestation

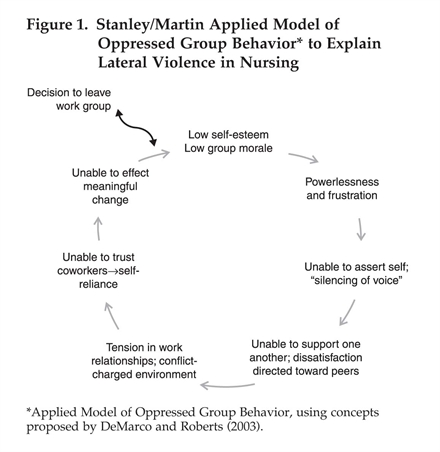

The proposed study supports organizational theories on clinical settings, and looks at the myriad of ethical implications in risk management decision on lateral violence, and is based on recommendations for investigation of those contexts. The research employs the Stanley/Martin Applied Model of Oppressed Group Behavior to Explain Lateral Violence in Nursing (2007). Figure 2 illustrates the psychological approach to morale building and leadership within horizontal nursing teams. Interpretation of the practice setting in the study encompasses, physical, psychological and property impacts in reported cases of lateral violence through utilization of diagnostic assessments, and includes an organizational survey, and SWOT analysis of the chosen case study environment. Review of best practices recommendations in application to transformation of practice organizations offers advancement of theoretical perspectives on lateral violence mitigation in healthcare organizations, and stands to contribute to scholarly discussion on the topic through of application of replicable measures and evidentiary conclusions to the study’s evaluation (Ramos, 2006).

Purpose

The purpose of the research investigation on lateral violence in a practice setting is to contribute to the professional dialogue on risk mitigation in the healthcare workplace. Outcomes to the study will provide valuable insights into the practical and policy spheres of the nursing profession as an incumbent to the development of hospital based safety programs, and national and international protocol standards. The investigation also proposes to promote furtherance of queries into the ‘duty to standard of care’ as acknowledged within U.S. Federal law, and with organizational sustainability and mitigation against risk of litigation and related employee complaints in mind. Protection of individual nurses as workers is of core interest to the examination, and the development of training programs, and real impact experienced in response to risk management interventions directed at lateral violence offers a burgeoning field, as risk is correlated to all aspects of the institutional environment as it systemically addresses complaints, and not merely financial or safety concerns.

Finally, patient care constitutes the primary landscape where much of the growing discourse on the topic is focused. Disruptive tendencies in lateral violence inevitably affect patients, and often put them in grave danger as nurses find themselves compromised. As indicated in the opening of the proposal, the most critical aspect of the interpersonal relationships between nurses and patients beyond hands on patient care is adequate knowledge sharing or non-disclosure. The study attempts to address this rather contentious, and rather unwieldy systemic factor, by way of instrumental application in the study’s implementation, and evaluation of those findings promises to ground the hypothesis through iterative analysis of incidence of imminent danger as indexed within hospital and legal record. Data generated from the latter will serve to inform the information gathered from the convenience sample survey and the SWOT analysis. Recommendations resulting from the study may be referenced in replicable investigations on the topic, and applied to the development of best practices ‘culture of safety’ educational curricula design, implementation and policy on lateral violence in healthcare organizations.

Research question

The research hypothesis is informed by Stanley/Martin Applied Model of Oppressed Group Behavior to Explain Lateral Violence in Nursing (2007) as illustrated in PICO(T) Format:

| P = | Patient Population is general |

| I = | Intervention/Issue of Interest is risk management of lateral violence in the practice setting |

| C = | Comparison Intervention is drawn from a Convenience Sample of Nursing Staff |

| O = | Outcome of findings will be disseminated in report form for peer review and potential publication |

| (T) = | Time of the study is one month |

Karen M. Stanley and Mary M. Martin’s (2007) research on nurse-on-nurse violence is a pilot test of an instrument to measure the presence of LV in practice settings toward intervention by nursing oversight. The proposed project will replicate the pilot with a micro measure that includes a parallel survey instrument. The Stanley/Martin test reveals that much horizontal hostility between nurses is fostered through internalized divisiveness, and reported low self-esteem which are typically indicators of anger in most research on female subjects in the United States. According to the study, the high incidence of susceptibility to LV is correlated to gender as 94% of the professional demographic segment is women. Disempowerment on the job is the number one cited cause for cycles of violence within female LV misconduct cases. To test this, the study employed a Silencing the Self Scale–Work (STSS) which provided indicators of oppressed group beliefs and behaviors, with subscales indicating compliance and care as ‘self-sacrifice.’ The data was supplemented by a Behaviours Scale (SNWBS) for factoring a subscales indicator of internalized sexism and minimization of self. The proposed research follows the Stanley/Martin model, and its findings which indicate minimized LV in staff exposed to applied cognitive behavioral techniques post investigation.

Background

Background to the aforementioned Stanley/Martin study sets the format for the current research, and strives to advance findings to the pilot with new information related to the revelations recorded on contribution of LV to intensified stress and tension in the workplace. Whether intentional or unintentional the presence of LV with critical care settings exceeds normative expectation. The paradoxical ‘duty to standard of care’ as clinical professionals with a high degree of responsibility to patients and to colleagues, represents a crucial area of organizational and leadership analysis, as systemic apprehension of widespread horizontal violence seems to elude adequate mitigation in the name of safety and professional dignity on the job.

Patriarchal hierarchies within the medical environment are fairly pervasive, and the balance of power may affect the patient, the hospital unit, and a nurse’s career satisfaction. In keeping with the impetus of the pilot study, which sought to apply sufficient methodologies to the incidence of LV in hospitals, the “concept resonated strongly with many participants who suggested further exploration [and] the Chief Nurse Executive (CNE) and division directors agreed with the staff” as the survey was designed to “measure the perceived incidence and severity of LV in nursing” (Stanley & Martin, 2007, p. 1261).

Literature Review

Gerardi, D. (2004). Using mediation techniques to manage conflict and create healthy work environments. AACN Clinical Issues: Advanced Practice in Acute & Critical Care, 15(2), 182-195.

The author outlines recommendation to practice of conflict resolution mediation in the nursing sector. Consultancy applications are discussed as ‘cognitive rehearsal strategies’ intended to empower nurses to delay automatic thoughts, and respond differently to lateral violence. The article is beneficial to the research toward recommendation of findings within training protocol.

Griffin, D. (2004). Teaching cognitive rehearsal as a shield for lateral violence: an intervention for newly licensed nurses. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 35(6), 257-263.

The article looks at ten (10) common definitions of lateral violence amongst nurses, and examines cognitive rehearsal as a method of mitigation within situations of lateral violence. Useful for thinking about variation in lateral violence determinants.

Martin, M. et al. (2008). Perspectives in Psychiatric Consultation Liaison Nursing The Role of the Psychiatric Consultation Liaison Nurse in Evidence-Based Approaches to Lateral Violence in Nursing. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 44 (1), 58-60. DOI: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2008.00149.x

Based on a psychodynamic model of consultancy liaison to the nursing community, the article provides post-pilot theoretical application for new models of lateral violence intervention in nursing teams. The authors propose that incorporation of psychiatric expertise offers built in assessment mechanisms for interpretation of ‘breaking points’ prior to action. The implementation of systemic solutions by consultant liaisons offers a new perspective on employee relations and conflict management.

Ramos, M. C. (2006). Eliminate destructive behaviors through example and evidence. Nursing Management, 37(9), 34, 37-38, 40-41.

Oversight practices within nursing have long adhered to traditional hierarchical assumptions within patient care units. Evidence based recommendations posit alternative approaches to mitigation of risky behaviors and their consequences which might affect patient care.

Stanley, K. M., Martin, M. M., Michel, Y., Welton, J. M., & Nemeth, L. S. (2007). Examining lateral violence in the nursing workforce. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 28, 1247-1265.

The pilot study on nurse-to-nurse lateral violence implements an assessment measure for examination of a convenience sample and offers open ended responds by participants resulting in a range of topics related to bullying and horizon of acceleration of hostility in an increasingly tense and understaffed sector of the workforce. Correlation of gender to level of responsibility reveals the prevalence of female LV in healthcare settings, and sabotage equivalent to the ‘glass ceiling’ in traditional corporate organizations upon longitudinal extension of the findings.

Theory

Theoretical consideration to the study has evolved from review of scholarly literature on lateral violence within the nursing profession, and the administrative, cognitive, and policy approaches for mitigation of risk in healthcare practice settings. Figure 2 illustrates the analytical framework applied to the cyclical confluences within LV as an environmental factor.

Figure 2

Figure 2: Stanley/Martin Applied Model of Oppressed Group Behavior to Explain Lateral Violence in Nursing

Application in the study reflects application of the Stanley/Martin oppressed group theory and the HBM approach to theoretical developments in the area, and positions interpretative strategies in keeping with their Perspective on Psychiatric Consultation Liaison Nursing (PCLN) (Stanley & Martin, 2008). Resolution of LV is shown to be best addressed by PCLNs, as they offer the necessary clinical preparation and objective expertise. PCLN strategies are usually followed-up by training. The dual PCLN and Training strategy is part of a holistic approach to intervention.

Proposed solution

Systemic solutions afforded through contract with PCLN can offer immediacy where organizational structure might otherwise impinge upon intervention with perpetrating nurses. They can also provide systemwide inputs in strategic planning and task force operations planning, which enhances the capacity of hospitals to ‘think’ better and ultimately respond adequately in the form of personnel policies, management processes, and employee benefits. The importance of the Stanley/Martin (2007) pilot test on LV provided the foundation for appropriation of the psychiatric consultation liaison recommendation into best practices protocol.

The activation of consultancy based strategies in advisement of both retribution and restorative justice in the work environment acknowledges employee complaints with appropriate mediation that might otherwise only be sought in the last resort through external legal services. The use of mediation in healthcare settings has increased in the past decade, and designated administrative staff’ seek new training options in conflict resolution that might lead to consensus building strategies and resolution of identified concerns (Gerardi, 2004). Organizational leaders within clinical institutions might benefit greatly from the training of a critical mass of diverse healthcare professionals in conflict management, lateral violence, and related error disclosure issues and process reviews.

Implementation plan

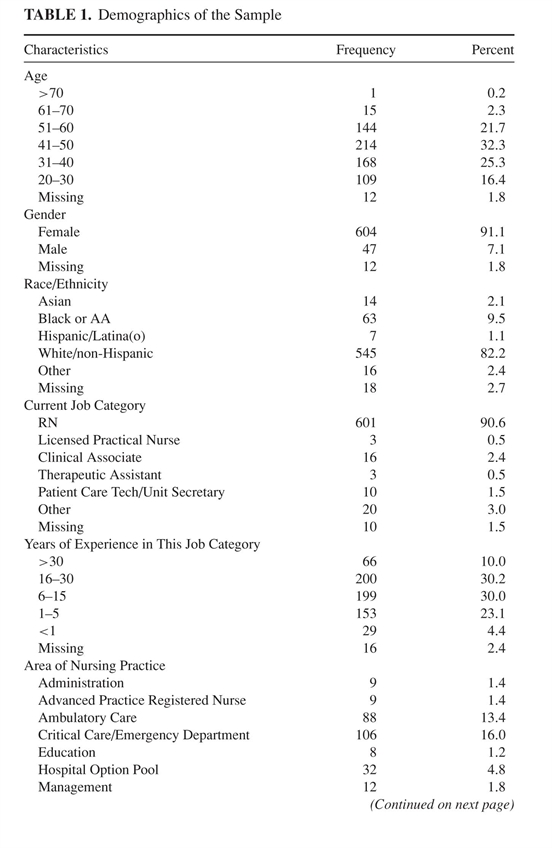

Methodological consideration in the study replicates the implementation of the Stanley/Martin pilot study research design, and incorporates both qualitative and quantitative analyses utilizing three constructs that reflect oppressed group theory and the HBM. To this end, the research design employs a tri-partite test application: Phase I: Testing; Phase II: Data Analysis; Phase III: Dissemination of Findings. Figure 3 illustrates an example of the survey population.

Figure 3

Figure 3: Survey Population Sample

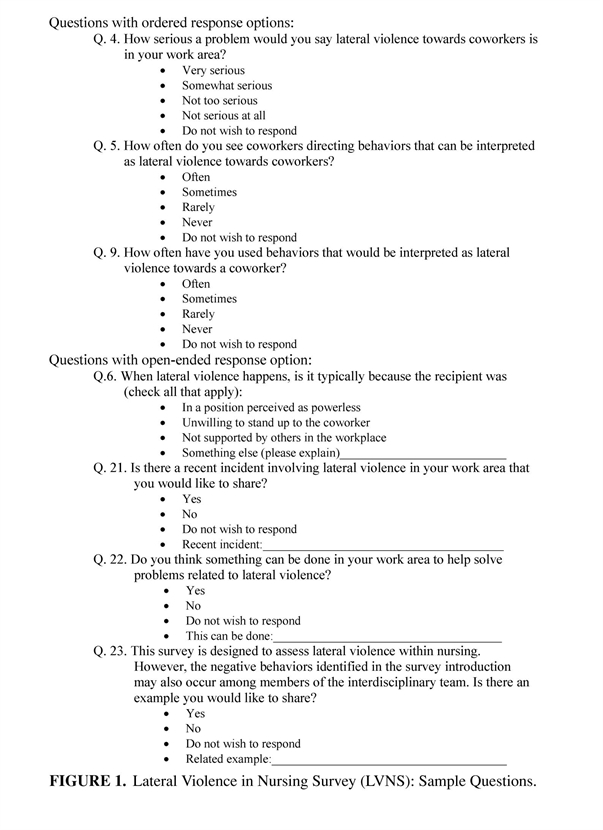

Sampling on the project will be drawn from a convenience study of a single tertiary care medical center adjacent to the University community. LVN survey respondents will be contacted by email, and requested to respond to the anonymous survey. Alternative access may be found through nursing alumni institutions which serve the institution locally. The survey will be administered through an online digital response panel. Figure 4 illustrates the format to the survey.

Figure 4

Figure 4: Lateral Violence in Nursing Survey

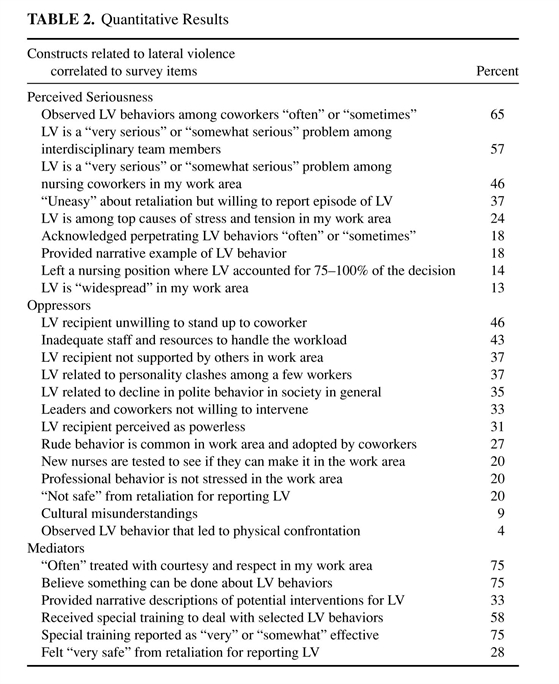

To measure the three constructs: 1) perceived seriousness; 2) oppressors; and 3) mediators an semi-structured survey with ordered or dichotomous items will be written as descriptions of potential occurrences or causes of LV. Demographic variables accounted for are age, gender, race, current job category, years of experience in this job category, and general area of nursing practice (Stanley et al., 2007). Informant agency is critical to the survey response panel. In most cases, negative influencers form bias to the objective of the study. The Survey interfaces with a Silencing the Self Scale–Work (STSS) which provided indicators of oppressed group beliefs and behaviors, with subscales indicating compliance and care as ‘self-sacrifice;’ and Behaviours Scale (SNWBS) for factoring a subscales indicator of internalized sexism and minimization of self.

Evaluation plan

Both qualitative and quantitative data collected in analysis on the survey will be analyzed using SPSSTM (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). Descriptive statistics will summarize the demographic characteristics and item responses of participants. Inferential statistical methods may be found if questions pertaining to causation of observed LV are applied. Qualitative analysis of the coded data will be useful for determining outcomes to query on the three constructs, and revealed by quantitative data analysis. Extensive narratives reported by respondents will be coded under the classificatory constructs for comparative analysis. Of particular interest is response to questions on education and effective leadership in relation to mediation of oppressive and negative behaviors, and potential exacerbation of lateral violence if not sufficient in the environment. Figure 5 illustrates potential quantitative results.

Figure 5

Figure 5: Results to the Lateral Violence Web Survey

Comprehensive survey outcomes, based on assessment of a particular group’s integrated complex of individual LV histories will offer much in the way of organizational analysis theory, as confidential self-reporting of incidence is otherwise prohibitive. There is strong evidence from recent data generated from web based survey tools that indicates that segmentation research benefits from direct informant insights. The potential of the data to further praxis in the area of advocacy on behalf of nurses and their grievances makes the survey of import beyond mere statistical accountability.

In addition to the methodological implementation strategy contained within the pilot replication research design, the Evaluation Plan a back end SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) Analysis will accompany the articulation of the evaluation for further integration of the findings in relation to the organizational analysis. Inclusion of the SWOT is intended as an instrument for recommendation of systemic solutions to the institution’s risk management strategy. The instrument also promotes participatory communication on the evaluation and prompts open ended discussion on potential conflicts arising due to operational or structural issues in the environment and promotes new service delivery models (Camden, 2009).

Dissemination of evidence

Conclusive to analysis of the survey data, the dissemination of the findings will contribute to scholarly dialogue on the topic at professional organizations, conferences, and journal publications. Include one professional publication or conference in your dissemination plan and explain why you chose this professional venue over another. Recommendations resulting from the study may be referenced in replicable investigations on the topic, and applied to the development of best practices ‘culture of safety’ educational curricula design, implementation and policy on lateral violence in healthcare organizations. Professional consideration on the study will also be applied to knowledge sharing servers for information transmission of the findings in the healthcare network.

Conclusion and Summary

The element of surprise in Tarasoff v. The Regents of the University of California transformed institutional obligations to legally binding protocols on ‘duty of standard of care’ and the dangers of intentional non-disclosure of information related to potential harm of another. The nebulous world of information sharing, and attendant patient right to privacy in the clinical and hospital setting are of keen import, as medical staff attempt to negotiate the rights of patients in the face of the requirement to protect colleagues from imminent danger.

The complications interjected into a work environment intensified by urgent care situations and tensions beyond the scope of normal risk to safety are of course the more serious aspects of lateral violence to nursing professionals, yet the broadening of rules regarding horizontal hostility have certainly expanded in the past decade. In interest of the advancement of evidence based practice as an innovative approach to change organization strategy, the proposed research is meant to foster the facilitation of internal evidence with external evidence, toward recommended best practices across multiple settings to improve patient, provider, community, and system outcomes.

References

The Workplace Bullying Institute. Center for American Nurses Lateral Violence and Bullying in the Workplace Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). www.osha.org

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). www.cdc.gov/niosh

American Nurses Association. (2001). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. Silver Spring, MD.: American Nurses Association.

Bartholomew, K. (2006). Ending nurse-to nurse hostility. Marblehead, MA 01945: HCPRO, Inc.

Camden, C. et al. (2009). SWOT analysis of a pediatric rehabilitation programme: A participatory evaluation fostering quality improvement. Center of Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation Research and the Estrie Rehabilitation Center. Quebec: Université de Montréal.

Center for American Nurses. (2007). Bullying in the workplace: Reversing a culture. Silver Spring, MD: Center for American Nurses.

Cook, J. K., Green, M., & Topp, R. V. (2001). Exploring the impact of physician verbal abuse on perioperative nurses. AORN Journal, 74(3), 317-318, 320, 322-327, 329-330.

Cox, H. (1991a). Verbal abuse nationwide: oppressed group behavior. Part 1. Nursing Management, 22(2), 32-35.

Cox, H. (1991b). Verbal abuse nationwide: impact and modifications. Part 2. Nursing Management, 22(3), 66-69.

Dunn, H. (2003). Horizontal violence among nurses in the operating room. AORN Journal, 78(6), 977-980, 982, 984-988.

Farrell, G. A. (1997). Aggression in clinical settings: nurses’ views. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25(3), 501-508.

Gerardi, D. (2004). Using mediation techniques to manage conflict and create healthy work environments. AACN Clinical Issues: Advanced Practice in Acute & Critical Care, 15(2), 182-195.

Griffin, D. (2004). Teaching cognitive rehearsal as a shield for lateral violence: an intervention for newly licensed nurses. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 35(6), 257-263.

Johnson, S.L. (2009). International perspectives on workplace bullying among nurses: a review. International Nursing Review, Mar2009, 56 (1), 34-40. DOI: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00679

Kelly, J. (2006). An overview of conflict. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 25(1), 22-28.

Kramer, M. (1974). Reality Shock: Why nurses leave nursing (1st Ed.). St. Louis, MO: The C.V Mosby Company.

Longo, J., & Sherman, R. O. (2007). Leveling horizontal violence. Nursing Management, 38(3), 34- 37, 50,51.

Martin, M. et al. (2008). Perspectives in Psychiatric Consultation Liaison Nursing The Role of the Psychiatric Consultation Liaison Nurse in Evidence-Based Approaches to Lateral Violence in Nursing. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 44 (1), 58-60. DOI: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2008.00149.x

Ramos, M. C. (2006). Eliminate destructive behaviors through example and evidence. Nursing Management, 37(9), 34, 37-38, 40-41.

Rosenstein, A. H. (2002). Nurse-physician relationships: impact on nurse satisfaction and retention. American Journal of Nursing, 102(6), 26-34.

Sheridan – Leos, N. (2008). Understanding Lateral Violence in Nursing. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 12 (3), 399-403. DOI: 10.1188/08.CJON.399-403

Rowe, M. M., & Sherlock, H. (2005). Stress and verbal abuse in nursing: do burned out nurses eat their young? Journal of Nursing Management, 13(3), 242-248.

Sofield, L., & Salmond, S. W. (2003). Workplace violence: a focus on verbal abuse and intent to leave the organization. Orthopaedic Nursing, 22(4), 274-283.

Stanley, K. M., Martin, M. M., Michel, Y., Welton, J. M., & Nemeth, L. S. (2007). Examining lateral violence in the nursing workforce. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 28, 1247-1265.

Tabone, S. (2001). TNA takes zero tolerance positions on physician abuse of RNs. Texas Nursing, 8-9, 11.

Task Force on the Prevention of Workplace Bullying. (2001). Report of the task force on the prevention of workplace bullying: Dignity at work-the challenge of workplace bullying. Dublin: Health and Safety Authority.

Violence in the Workplace: Position Paper (2008). Washington State Nurses Association, march 21, 2008.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee