The Future of Communication Media, Essay Example

Abstract

In this paper I discuss four points regarding the future of communication media. I begin with a short discussion of predictions of our cultural and technical future in general; why they fail; and why they are likely to continue failing. I then discuss two past failed predictions: the future of commercial pornography as a part of mainstsream filmmaking; and the future success of mainstream interactive movies. Discussion of the two includes the role of technology in the hoped-for success of these two predictions, and the role of technology in their failure. I then make a prediction of my own regarding the future of media and its technology.

The Future of Communication Media

Predictions of the future are not really predictions for long, because they so quickly become out of date. Instead they rapidly decay into unintended time-capsules, showing the future what the past was thinking when it thought about its future. This has happened over the years with such persistence that a kind of literary cottage-industry has arisen around past predictions of the future. Books like Where’s My Jetpack?: A Guide to the Amazing Science Fiction Future that Never Arrived have brought the history of failed utopian-styled futures to an amused mass audience (Wilson).

Among that audience are those who may remember seeing artifacts of pop-culture heritage dating back to the first sci-fi pulp magazines of the 1920s, with a detour at the New York World’s Fair of 1939 with its then-futuristic exhibits that included freeways winding between skyscrapers in kind of streamlined dream of efficiency and ease. This paper will turn out the same way, fated to be either ignored, chuckled over, Laughed Out Loud at, or — this the least likely — cause a few eyebrows to be raised in quiet acknowledgment of my amazing foresightedness and clear thinking. But the above retrospectives involve decades. Will this paper even be safe for the next ten years? A decade is not really a very long time, but that a difference a decade can make.

We can get an idea of predicting within a decade’s horizon. Rather conveniently, Wired magazine did a story in 2003 entitled Living in 2013 (Zjawinski). The results are rather what you would expect. Some of the predictions nearly turned out nearly right — there is a predicted sort of Google Glass for athletes — but others, such as the mobile food-analyzer and super-smart earplugs are at best a few years away from realization and seem a bit questionable. But the positive suggestions about what the future of 2013 held is only one side of the coin. The other side is what the article didn’t contain: on the day the Wired article was published in April of 2003, Apple’s iPhone was four years away. Facebook was launched as a campus-only website in 2004, as was Flickr. The now-ubiquitous Facebook Like button arrived in 2010. Twitter was three years in the future, and Instagram was seven. Tumbl debuted in 2007.

Nothing of such services is hinted at in the Wired article. That’s because these services are disruptive uses of technology, not evolutionary ones. The late urbanologist Jane Jacobs referred to such changes as bifurcations or discontinuities (Jacobs). Whatever you call them, they are probably impossible to predict, either as to what specifically will spring forth as from a dragon’s tooth, or when — until some individual thinks up the one idea that will constitute such a change, which then leads to a cascade of other changes.

The author of the Wired article, Sonia Zjawinsky, was evidently no visionary, but instead a freelance writer on an assignment. Writing skills aside, anyone could have done it, and I will try my hand at it myself in this paper. Her ideas were from the grab-bag of the public domain, as it were, as will be mine. Having an idea is one thing, while getting the technology and money to make the idea work is another. Zjawinsky had no intention of becoming an entrepreneur (and has not done so). The ideas she submitted were not terribly imaginative. I have no immediate plans to make my own idea work either. And this may be true of all authors of articles and books that try to predict the future. We have no skin in the game. We are futurist kibitzers. It may be that all “futurists” are kibitzers in practice.

Marketing Basics

The arc of media marketing is acceptance, monetization, and confluence. I will begin with some quick definitions, although these terms are fairly self-explanatory even to non-students of online marketing. But first it should be noted that these are not necessarily in chronological order. Mass acceptance of a platform, program, or whatever might first require its confluence with other platforms and programs. This can lead to monetization. If anything, monetization tends to come last as start-ups burn through their money and seek additional financing even as their product is becoming more and more popular without making money. The leading example of that is Google, which did not make money until it learned how to measure the readership of its ads — and at first no one knew how to make ads work. And so at first Google did not make money. When it did, the confluence of Google with growing mobile technology was well on the way. Monetization assured Google’s viability as both a search engine and the world-changing multipurpose site it has become. Competitors, like Microsoft’s Bing, are far behind.

Acceptance is understood by everyone and so I won’t bother to formally define it here. But degree of acceptance is another matter. On the Web “acceptance” is not what it means for candy bars, a new car, or a new kind of coffee at Starbucks. There is a whole order of magnitude of difference between buying something physical in person in real time and ordering something online, or posting something on a merchant’s social-shopping site, or your Facebook page, or sending an Instagram. These are working examples of confluence — the coming together of two or more different streams of platforms, thought, commerce, communication, and, of course, money-making, aka monetization. This five-syllable marketing word means different things in different contexts, but in the context of Web media, it essentially means to turn banner and Google side-bar ads into money based on the number of people who click them.

Media Content, Production, and Technology: Past, Future

Now we come to the nub of the matter: how will communication media of the future work and what will it be saying and selling? The answer will determine what our world will look like and sound like, and where it will be found (or perhaps where it won’t be found, if anywhere). We can look around our own homes and offices as a starting point in a more or less haphazard way, guessing our way around and making various futuristic predictions about the future of TV, microwaves, stoves, phones, computers, cars, and the house or condo itself. But how valuable would that exercise really be? We know how past predictions of the technical future have turned out, predictions of disruptive uses of even present technology being impossible to make successfully with anything beyond random luck. But we’ve also got to consider the disruptions caused by technology that has not been invented yet. That is also where so many predictions of the future go wrong. Successfully predicting both kinds of changes is out of the question.

The future of media overall is a subject far too wide to cover here, so I will narrow it down by discussing two past predictions about media content, production, and technology that failed, and from those two make a prediction of my own. This will involve a lot of history, which I take to be acceptable from our class rubric, which says to make “. . . multiple and detailed comparisons between the prediction and history of media products.”

Mainstream Pornography

There was a time back in the mid-1970s and early to mid-1980s when people thought that hard-core pornography, once shot with Super 8 film and relegated to store-front theaters in downscale and/or declining downtown neighborhoods, would converge with mainstream media. This change in mindset about pornography came about when the 1972 pornographic film Deep Throat reached a mainstream audience, making millions of dollars. Even Jackie Kennedy Onassis publically showed up to watch it one night in New York — as did the mayor (Bailey). Looking ahead, it was thought that this could be the start of a trend. And for awhile, it looked like that might be the case. Technology helped. After Deep Throat, porn-audiences boomed and Super 8 could be dropped in favor of better cameras and film. Porn-production values soared. Porn-films were shown in large-sized theaters as well as grindhouses. Porn seemed to be on the cusp on mainstream acceptance by polite society.

That did not happen. The failure of what we might call the convergence theory of porn and mainstream media can be seen in the 1997 movie Boogie Nights. Although it originally contained explicit scenes, they were cut to reduce the movie’s ratings from NC-17 to R. As a result, a movie about the porn industry and co-starring the former porn actress Nina Hartley has no actual pornographic scenes in it. In other words, years after porn almost went mainstream, it had not been able to achieve the confluence of mainstream audiences with the rather sizable porn-movie audiences to overcome the political powers that maintained ratings system. Although porn is something that can be monetized on the Web and off, it cannot go beyond a certain point. Today a barrier exists separating mainstream Websites and pornographic ones: you will not see links to porn on the sidebar of a Time.com webpage that aren’t relevant to a story. But there is another reason porn failed to achieve confluence.

Explicit and graphic depictions of just about anything tend to destroy the artistic sense of any serious, dramatic picture. To see what I mean, try imagining a big-budget drama today featuring an explicit depiction of brain surgery. It would shock too many sensibilities, completely destroying the artistic world the movie was trying to create — it would take viewers out of the story, which is something that can never be done. Even today, explicit sex does exactly the same thing. You can give people quality drama or comedy, but you cannot shock audiences out of their critical suspension of disbelief required for any artistic production.

Finally, technology, which has often brought new values to a mass audience,[1] ended the so-called “golden age of porn” of the 1970s and 1980s. The VCR and videocassette took porn indoors (it never having achieved full public-viewing respectability) and porn in turn made the VCR profitable, which then led to its confluence with mainstream media as more and more theater-quality releases were re-released on cassette. Porn was largely private again, allowing the lid to be put back on publicly available depictions of sex until the arrival of smartphones and their photo- and movie-making apps, instantly sent to anyone. Facebook postings and visual sexting and the Web in general have changed many people’s attitudes about what can be done about porn and what cannot.

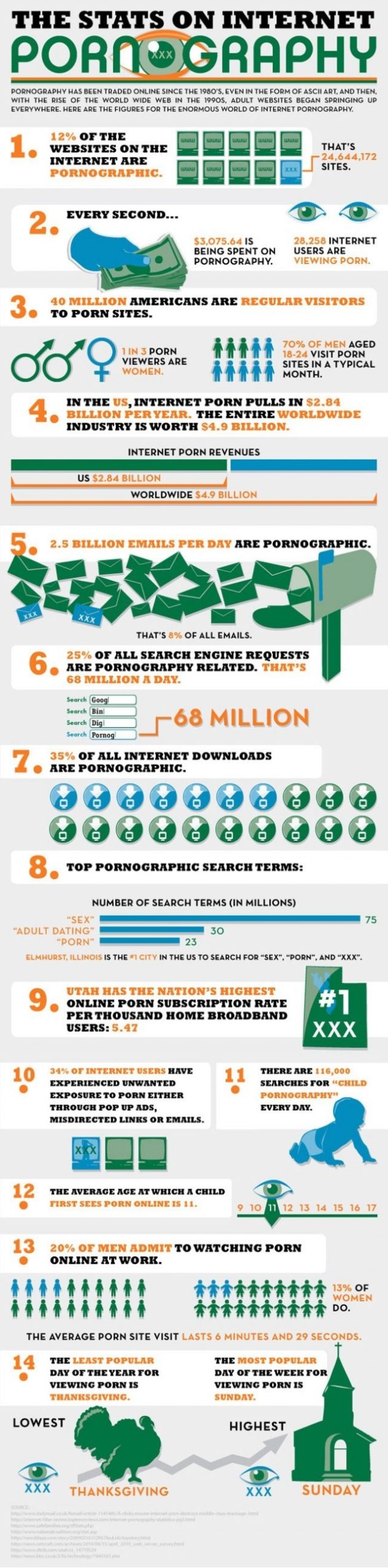

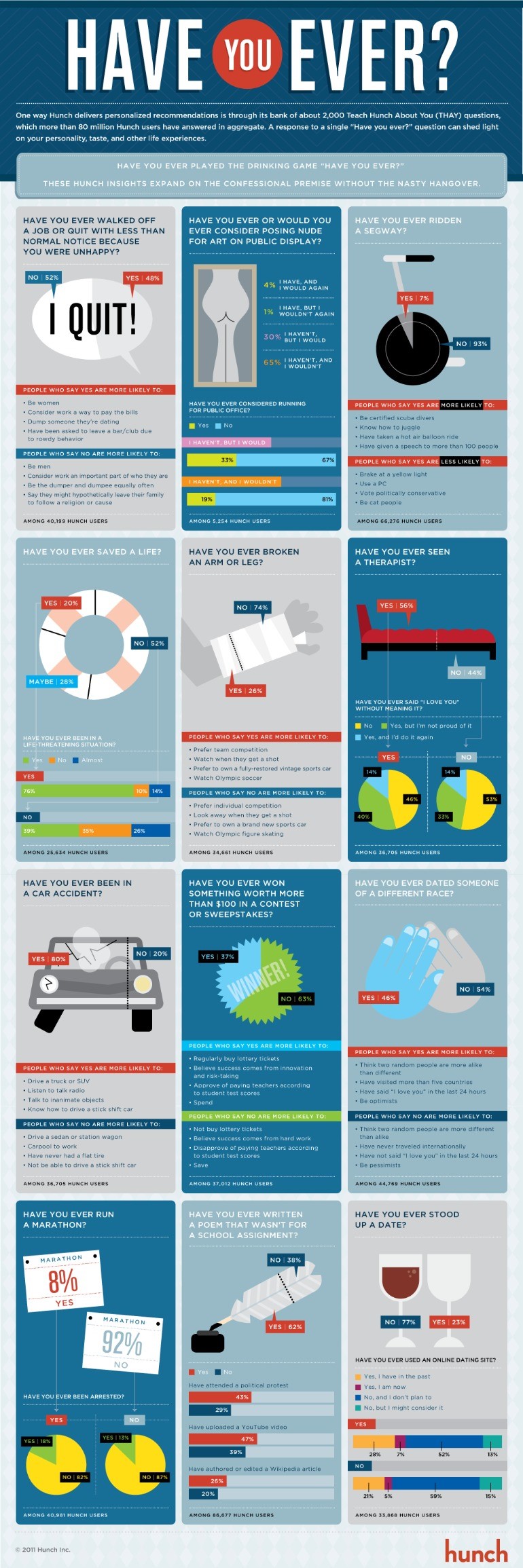

Porn has exploded in popularity far beyond anything known before.[2] But for all its ubiquity porn remains segregated in a parallel universe. (It was Hugh Hefner’s genius to be able to nearly straddle both worlds: Playboy was never X-rated.) At least in its movies and certainly on the Web, porn is porn, not publicly acceptable art. Sex remains an ambiguous public activity[3] — Anthony Weiner’s photo-sexting case seems to have pretty much ended his political career, indicating that for all our acceptance of the inevitability of porn in the age of the Internet, the moral standard of our parents and grandparents become our own.

Interactive Movies

With the arrival of PCs and Macs came games and interactive media. One of the early hits of interactive media was Sim City. The technical term for this kind of game is nonlinear gameplay. What that means is that the ending is not set in advance but is dependent on input from the players. Games are the ultimate expression of interactive media and have definitely achieved Web monetization and confluence with users of desktop, laptop, and mobile platforms like tablets and phones. The growth and popularity of nonlinear games once led some people to speculate whether the same principle would work with mainstream movies — audience participation movies. And this applied to gaming as well when graphics improved to the point of allowing near movie-quality graphics. Lots of those games sold by the millions, which basically made them into movies.

But interactive mainstream movies were not all that new an idea. The first (and almost only) interactive movie was Kinoautomat, a Czech movie shown at the Expo 67 in Montreal. The film stopped at one critical point and the host asked the audience to choose between two possible outcomes — a technique that required two projectors. This was the first indicator of a problem: the expense of added equipment in theaters that would not be showing interactive movies all the time. This proved fatal. In 1992, the Lowes theater chain installed special equipment for the audiences of I’m Your Man. The experiment was a commercial failure, but was tried later in an last-ditch attempt at interactive home-video. But the problem was the same — expensive special equipment with an insufficient customer-base (unlike, say, the Xbox platform) and decision-making that destroys the artistic moment of watching a performance. The only way to avoid that is to make the interaction continuous, and that can only be done during a game. Interactive media is for computer games, whether mobile, desktop, or in video parlors. Which means it is for users who like games, and that generally means users well under the age of forty.

My Prediction

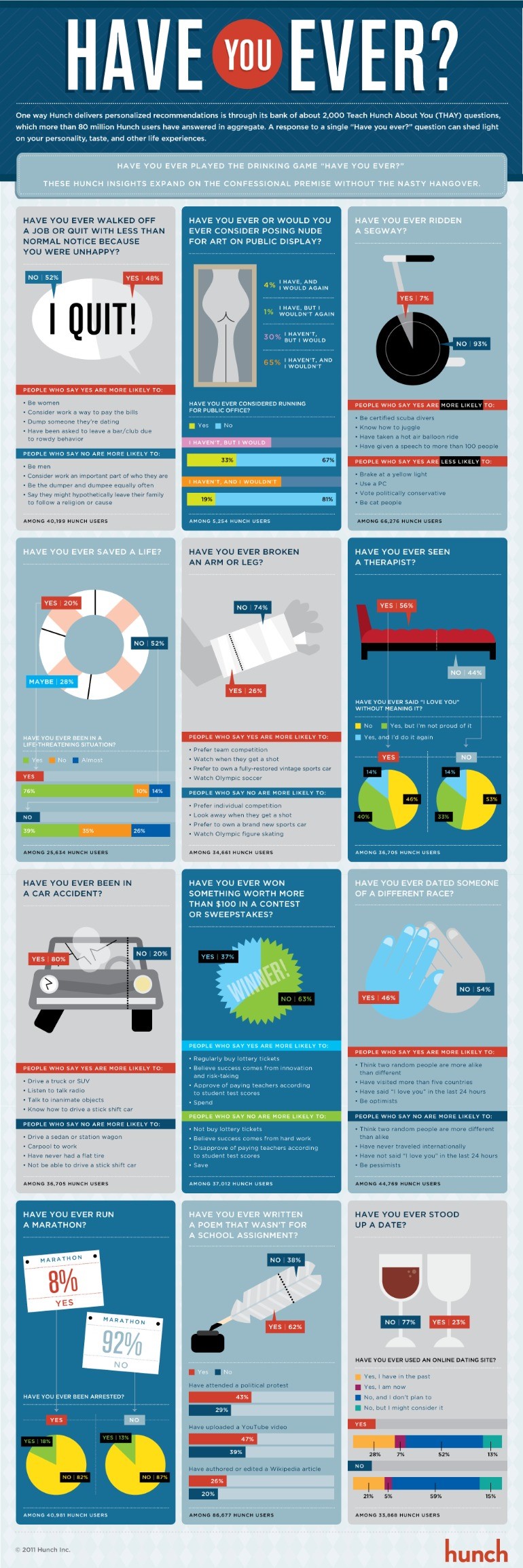

Now it is my turn to make a prediction ten years into the future about some aspect of media content and its production, and whether it will achieve acceptance, confluence, and monetization. It involves Google Glass. My prediction is that its technology will have permeated society by 2013 like the smartphone has since 2007. But for Google Glass itself, my prediction is that as a unique patented device it will have gone the way of the Segway. Prior to that product’s release in 2001, it was the subject of intense media hype. It was predicted that it was going to be as important as computers and the Internet. But the Segway has not gained mass acceptance,[4] and beyond its sales, has no monitizable mass-confluence with other activities and therefore no large media presence, although it is far from a failure.

What I see instead is the use of eyeglasses (not contact lenses) that can receive and send information like Google Glass can do, but that its technology will, like smartphone technology, have moved on from its inventor to open source and open tech. But that is only half of the equation of the future. The other half is what I’ll call generic Google Glass Tech (“GGT”) — which will include a microphone and earpiece — and what I’ll call Display Technology (“DT”).

It is now 2023. You are riding in a car or on a train or bus (they’ll still be around). You are wearing a GGT set. But now any random blank brick or stucco wall may be covered with a coating of DT to make a Display-Tech Space (“DTS”). This is not a fantasy. Funded research began in 2005 (Case Western Reserve University). So physical spaces have replaced the Google Glass projection gizmo now used. Such DTSs are now installed inside buses where static ads were, and anywhere else display-ads were. That’s where you now receive your encrypted Snapchat-brief text messages, news — and ads. But now you see them only when the DTS is in view — your GPS and GGT know where you are and where you are looking. (To limit encryption requirements, certain DTS are like mass-broadcasting channels that you used to tune to.) The DT processes as many GGTs as are looking at it. You safely drive and receive messages because they are no more distracting than looking at an old fashioned billboard used to be. You pass one DTS and continue reading the same message on the next one down. Many of yesterday’s billboards are now DTS’s, as are apartment-house walls. Owners of such walls and billboards receive fees based on how many eyeballs they attract. As you make your way through your day, glancing at certain walls and spaces has long become second nature.

Currently Google Glasses cannot be fitted for prescription lenses. GGT will by 2023. The key point of convergence may be whether GGT, DT, and DTS’s get enough people to forgo Lasik surgery and contact lenses. After all, if they are wearing GGT and reading DTS’s all the time anyway, why not just use the lenses for visual correction as well? This may be the deciding factor in getting the widespread acceptance of GGT — whatever the manufacturer — to earn its confluence with other technologies and so lead to monetization of media that is broadcast to and from the GGT and DTS. That final stream of confluence may just be the killer app to guarantee profitability of GGT and DT technology.

We have seen how two past media predictions failed. In retrospect, it seems obvious that they would, yet at the time people spent money thinking they would succeed. But GGT and DT will not be dependent on developing a new artistic sensibility. They will instead be an evolutionary refinement of present technology. That leaves open disruptive technologies to come. Evolutionary or disruptive, cost alone will determine success.

Time will tell.

For reasons of space, the images below are clips. Sources are given for each complete version.

Infographic 1

http://dailyinfographic.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/internet_porn-640×2590.jpg

Infographic 2

Infographic 3

http://dailyinfographic.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Hunch-Have-you-Ever.jpg

Infographic 4

Works Cited

Case Western Reserve University. Paint On The Wall TV Screens? Case Chemist To Design Chemical Building Blocks For Such Potential Use. 31 March 2005. 5 December 2013. <http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2005/03/050329140351.htm>.

Honan, Mat. The Future Is Now: What We Imagined for 2013 — 10 Years Ago. January 2013. 2 December 2013. <http://www.wired.com/gadgetlab/2013/01/2013-the-way-we-were/>.

Inside Deep Throat. Dir. Fenton Bailey. 2005. Film.

Jacobs, Jane. Cities and the Wealth of Nations. New York : Vintage Books, 1984. Paperback.

Wilson, Daniel H. Where’s My Jetpack?: A Guide to the Amazing Science Fiction Future that Never Arrived. New York: Bloomsbury USA, 2007. Paperback.

[1] The cellphone has socially legitimized distracted driving, making it fashionable in the process.

[2] See page 10, infographic #1

[3] See page 10, infographic #2

[4] See page 10, infographic #3.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee