In-Class Double-Student Peer Review, Article Writing Example

Abstract

In-Class Double-Student Peer Review Prior To Submission: The Pros & Cons

Whether the course instructs EFL/ESL (English as a Foreign Language/ English as a Second Language) students or is a Composition 1, Composition 2, or Business Writing course, the ultimate goal is to improve the writing and communicative abilities of those receiving instruction (Goldenberg, 2008). However, many studies have demonstrated that even professionals have insufficient writing aptitudes (Quible & Griffin, 2007). The purpose of this study is to measure the pros and cons of the peer review learning strategy when implemented as an in-class double-student strategy prior to student submission of their work in order to demonstrate the significant benefit potential that can be realized from consistent use. There are a multitude of beneficial attributes associated with peer review that are overlooked since peer review is often underused in professional and educational settings. Through mixed qualitative and quantitative research methods, this study will demonstrate the improvement achieved using in-class double-student peer review as a learning strategy to improve student writing. Over the course of three years, this study encompasses 480 students that attended a total of 24 Freshman Composition 1, Freshman Composition 2, or Business Writing classes that I have taught. The overall results of the study support the position of this author, which is that the majority of the students that were participants of the in-class double-student peer reviews indicated that they felt stronger in their English abilities and were able to write clearer, had better comprehension when reading, and it became easier to identify their peer’s writing errors as the course progressed.

Keywords: Peer Review, Folder Method, Peer Assessment, Student Review, Student Writing, Elf/Esl, Learning Strategy, Peer Feedback

Introduction

The intention of this study is to examine factors that affect student achievement and provide information to the field of education about the benefits of including peer review as part of the tools included with successful implementation of change initiatives to improve student writing (Moore & Teather, 2013). Throughout this literature, the term “peer review” will be defined a structured process in which peers review the products of each other’s professional or educational processes with the intent of helping to improve such products (Brill & Hodges, 2011). The percentage of students struggling with their writing or linguistic skills in elementary school contributes to the number of future “at-risk” students that will potentially drop out of high school (Ball, 2010).

As educators, it is the responsibility of the teacher to implement an educational change initiative that will close the learning gap for underperforming students. Increased student achievement requires teachers with meticulous pedagogical skills and high self-efficacy to influence the learning environment (Goldenberg, 2008). Since children often learn and develop social habits in accordance with the actions and norms of their peers, a great method to help children learn is by allowing scaffolding to occur through the process of peer review (Campbell, Combs, Kovar, Napper-Owen, & Worrell, 2009). Although previously considered as a negative by educators, this examination of the in-class double-student peer review process intends to demonstrate the numerous benefits to students and teachers that can be realized through the consistent, integrative use of peer-review methods.

Research Question

As an educator, I work diligently in my writing classes to help my students gain confidence in their use of English throughout the semesters by having students provide feedback on their peers’ papers using two response methods. The student reviewing the paper is instructed to provide comments using annotations on their peers’ papers, as well as oral feedback through discussion. Since integrating this two-fold peer review method, I have noticed that students are able to better edit their own papers much more carefully and correctly. This observation has inspired the development of the primary research question for this study, which is: Should students conduct in class peer-reviews twice before submitting their final essay? It is the contention of this author that peer review provides numerous benefits for students, with the most positive element being the development of self-efficacy and confidence in their writing or communicative abilities. The confidence is gained through the development of beliefs in their own abilities

This research will examine the pros and cons of using peer review methods, such as the in-class double-student peer review process and the Folder method, to assist students in improving their literacy skills. Since literacy includes reading, writing, and comprehension, these three elements will be discussed in the Literature Review to provide the supportive detail regarding improvement of written communication. This section will also discuss the impact of the teacher and the learning environment on the educational outcomes of the student. The next section will detail the Research Methods used to accumulate the data presented in the Results and Discussion section of this paper. The Results and Discussion will review and analyze the findings gathered from the implementation of the in-class double-student peer review method and the Conclusions will summarize the research and detail observed Limitations.

Literature Review

The pressure to perform academically has always been a significant source of stress for students. Parental pressure to excel and gain admission into the best schools can be extreme. Additional research has determined that the academic test scores of some students can be used as predictors of their overall degree of life satisfaction (Wei, Brok, & Zhou, 2009). The scholastic environment is intended to act as a cushion and protect the students’ psychological well-being as they develop. Research has indicated that a teacher’s effect on their students is often the result of the students’ psychological responses to the teacher’s behavior (Sadker & Zittleman, 2009; Samson & Collins, 2012).

This makes the use of student perceptions both valuable and necessary when evaluating the learning environment and in scrutinizing its effect on learning outcomes. The scholastic or learning environment includes factors, such as the level of supportive services available through school forums and the classroom context, which includes any language barriers that may exist, as these elements are also directly related to scholastic achievement in writing, as well as other learning areas (Sadker & Zittleman, 2009). The numerous studies conducted on the effect of the classroom environment, support of the educator, the student’s sense of belonging within their academic surroundings, academic achievement, and peer interactions on the self-perception and moods of the students has revealed that these factors have a direct influence on learning and classroom behavior (Hertzog, 2011; Nassaji & Fotos, 2011; Samson & Collins, 2012; Wei, Brok, & Zhou, 2009). This enables the use of peer review to significantly contribute to the educational experience of students by providing a unique instructional method that will enhance retention of the material (Boase-Jelinek, Parker, & Herrington, 2013).

Impressions of the Pros & Cons of Peer Review

As previously iterated, it is the contention of this researcher that peer review provides a multitude of benefits to both the student and the teacher. Although the purpose of this research is to demonstrate the truth of this position, the purpose of this portion of the Literature Review is to effectively represent both sides of the argument so that inaccurate beliefs represented in popular literature can successfully be debunked. The most commonly stated cons will be discussed first followed by the justifications supporting the pros associated with peer review.

Cons of Peer Review

Researchers and critics perceive peer review as a process of the “blind leading the blind” since it involves inexperienced editors coaching novice writers (Liu & Chai, 2009). Furthermore, research has illuminated the tendency of some students to avoid providing any direct negative feedback due disparities in cultural norms and as an alternative offer positive or mitigated remarks for their peers (Wang, 2009). An additional tendency noted by some researchers is for the power structures created through these writing groups to encourage communal inaccuracies in groupthink situations that reinforce conformity rather than negotiate new meaning (Brammer & Rees, 2007). Although students value peer review, they often give poor advice to peers they wish to please or impress and, in classrooms that have a mixture of EFL/ESL and native speaking students, peer review is typically most useful to those most proficient in the target language (Kao, 2013; Lan, 2009). In such circumstances, the students that are inexperienced or non-native speakers tended to make minimal or surfactant suggestions, while experienced writers make meaningful revisions suggestions to improve others’ essay quality (Wang, 2009). In these instances, students have expressed displeasure with peer review because their peers do not catch all their mistakes and they interpret the process as a waste of time (Brammer & Rees, 2007).

Educators have expressed displeasure with the peer review process because they state that students’ papers remain of poor quality because the writer did not stay on task and the reviewer did not correct the error during the peer review process (Brammer & Rees, 2007). Initially, the peer review method was exclusively used in educational settings that emphasized decentralizing the role of educator, which placed the technique as a cutting edge, progressive methodology (Brammer & Rees, 2007). However, instructors often indicate a conflict in aims that tends to emerge when forming peer review collaborative groups, such that socializing becomes the focus of the interaction above academic improvement (Brammer & Rees, 2007). Furthermore, many educators are concerned with how much their students can actually learn through the peer review process (Timmerman & Strickland, 2008). Finally, even when students developed high levels of confidence in the peer review process over time, they remained skeptical regarding the fairness and consistency of the peer review process (Kaufman & Schunn, 2011).

Pros of Peer Review

Peer review is not a new pedagogical technique and theorists endorse the use of instructional methods that encourage active participation in the learning process, use of complex problem solving skills, engaging experiential approaches, the inclusion of group activities, and innovative inclusion of current technology (Barst, Brooks, Cempellin, & Kleinjan, 2011). Research has determined that such use promotes student communication and collaboration, active problem solving, critical thinking, decision-making, and a concept called digital citizenship, which describes a positive attitude toward using technologies that strengthens collaboration (Brill & Hodges, 2011). Using peer review benefits both teachers and students because it allows instructors to integrate more writing assignments without increasing their personal workload, which provides students with more opportunities to practice their writing skills (Poschl, 2012). In this manner, peer review helps improve student content knowledge through writing and strengthens their reasoning skills (Timmerman & Strickland, 2008). Furthermore, research asserts that effective peer review frameworks use a strong collaboration component as a strategy for determining timely tiers of supports to help students gain academic proficiency (Brill & Hodges, 2011). Among other benefits, students reported that peer review improved their general content knowledge, their scientific writing skills, as well as directly impacting the assignment at hand, and their critical thinking skills (Timmerman & Strickland, 2008).

Theoretical Framework Supporting Peer Review

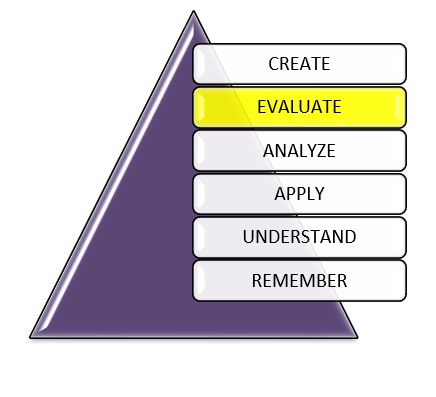

The peer review learning strategy is considered as an educational method among the highest cognitive areas of Bloom et al.’s taxonomy of the cognitive domains (Brill & Hodges, 2011), as illustrated in Figure 1: Revised Hierarchical Structure of Bloom et al.’s Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain, as cited by Huitt (2011) and adapted from Wilson (2006), where the highlighted level of ‘Evaluate’ represents the cognitive level required to perform peer review.

Figure 1: Revised Hierarchical Structure of Bloom et al.’s Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain

This hierarchical structure is better conceptualized in the definitive explanation detailed in Table 1: Revision of Bloom et al.’s Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain with Knowledge Dimensions below, as cited by Huitt (2011) and adapted from Anderson et al. (2001), where the highlighted cells under the ‘Evaluate’ heading represents the degree of cognitive skills necessary for students to perform peer reviews.

Table 1: Revision of Bloom et al.’s Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain with Knowledge Dimensions

| Cognitive Process Dimension | |||||||

| Knowledge Dimension | Remember | Understand | Apply | Analyze | Evaluate | Create | |

| Factual Knowledge | Terminology Elements & Components |

Label map List names |

Interpret paragraph Summarize book |

Use math algorithm | Categorize words | Critique article | Create short story |

| Conceptual Knowledge | Categories Principles Theories |

Define levels of cognitive taxonomy | Describe taxonomy in own words | Write objectives using taxonomy | Differentiate levels of cognitive taxonomy | Critique written objectives | Create new classification system |

| Procedural Knowledge | Specific Skills & Techniques Criteria for Use |

List steps in problem solving | Paraphrase problem solving process in own words | Use problem solving process for assigned task | Compare convergent and divergent techniques | Critique appropriateness of techniques used in case analysis | Develop original approach to problem solving |

| Meta-Cognitive Knowledge | General Knowledge Self Knowledge |

List elements of personal learning style | Describe implications of learning style | Develop study skills appropriate to learning style | Compare elements of dimensions in learning style | Critique appropriateness of particular learning style theory to own learning | Create an original learning style theory |

As the table illustrates, critical thinking skills are essential to any student’s ability to review their peers’ work (Huitt, 2011; Wilson, 2006).

The strong impact of the preliminary use of peer review learning strategies has entrenched these methods into educational routines as deeply as the traditional lecture, write, and correct routines (Brammer & Rees, 2007). To stay current with the syllabus, many teachers employ lecture-type methods of instruction that can account for an average of 50% of lesson time and causes disinterest among students (Goldenberg, 2008). Research has demonstrated that approximately 53% of junior secondary EFL/ESL students indicated that they find it difficult to understand subjects taught in English (Liu & Chai, 2009) and more than 40% of EFL/ESL students indicated that they are only able to comprehend less than 60% of the lessons taught in English (Nassaji & Fotos, 2011). The lack of available educators that are proficient bilingual speakers of the native and/or target language and can successfully engage students to help them maintain their native tongue while learning the additional language impedes the ability of the student to progress at the same pace as their native-speaking peers (Ball, 2010). In such settings, students that are slower learners typically loose motivation and resort to disruptive classroom behavior.

Impact of the Instructor on Peer Review Outcomes

The application of the social cognitive theory revealed that student achievement is influenced by the perceived self-efficacy of the teacher (Hertzog, 2011). Social cognitive theory was developed by Albert Bandura and posits that the social environment influences the development of behavior, as well as learning and this theory was extended to emphasize the role of self-efficacy as a key structure for examining psychological procedures, which directly impacts the strength of individual self-efficacy (Decker, Decker, Freeman, & Knopf, 2009). The teachers’ perceptions of self-efficacy create classroom environments that can strengthen or weaken the students’ own sense of efficacy (Sadker & Zittleman, 2009). Perceived self-efficacy is rooted in social cognitive theory because the level of belief in one’s own abilities empowers the individual to produce the desired effects, making it both the incentive and inhibitor.

The phonological competence of the instructor is also a key contributing factor in literacy acquisition (Crim, et al., 2008). Successful literacy acquisition is contingent on the educator’s ability to adequately instill phonological awareness skills in addition to a strong understanding of language structure (Crim, et al., 2008). Pragmatic linguistic knowledge means that the individual is aware of the overall intent of communication and how language can be used to accomplish that objective (Brill & Hodges, 2011). Peer review can help reinforce this pragmatic understanding by representing how written language can be used to articulate purpose (Trautmann, 2009). The elocution and linguistic variations assumed are also substantiation of the improvement of the development of registers and pragmatic linguistic knowledge (Otto, 2010).

How Peer Review Helps Language Development

The social setting also plays a significant role in student development of linguistic diversity, especially for EFL/ESL (English as a Foreign Language/English as a Second Language) students. The presence of concrete referents that contribute to symbol formation and conceptual development also has a primary role in the acquisition of linguistic knowledge of the target language (Ma, 2012). The primary determinant is based on the individual that is modeling the target language and their linguistic development (Hertzog, 2011). Despite the continual support for a standard lexical definition of the English language, the consistently shifting dynamics of modern society makes demand that such an establishment would, by default, also have to constantly be changing to remain accurate.

Mastery of proper grammar and diction is vital in any method of communication, particularly in written messages. The purpose of proper grammar is to assist in precise communication absent the physical presence of the sender, so written documents must be precise in order to assist in conveying an accurate version of the author’s perceptions, thoughts, and position regarding the topic of the document (Crim, et al., 2008). Although the subject of English is consistently taught throughout the average student’s academic career, the importance of it is never adequately stressed as a lifelong tool for communication. Additionally, some teachers have worse grammar than the students they are supposed to be teaching, resulting in a conundrum of confusion for the student that they carry with them throughout their academic career.

Effectual Methods of Peer Review

Like any learning strategy, the efficacy of the peer review method is contingent upon the manner and consistency in which the instructor implements the activities. As a prelude to each engagement, the instructor should be precise in discussing with students the benefits to the person in the role of peer reviewer and the individual whose work is being reviewed (Lawson, 2011). Further research identifies the importance of helping students recognize their peers as effective reviewers capable of providing useful feedback that can help the author improve the quality of the paper if incorporated (Hartberg, Gunersel, Simspon, & Balester, 2008). This emphasizes the importance of clearly delineating the parameters that distinguish what constitutes as ‘useful feedback’ and implement accountability guidelines that reward students that genuinely attempt to provide relevant feedback (Timmerman & Strickland, 2008).

In situations where web-based peer review tools are used, it must be understood by the facilitator that such methods differ from traditional face-to-face writing instructional contexts, but they also allow students to envisage their thoughts to assist in the problem solving aspect of writing, which can be complicated (Yang, 2011). Interactively designed assignments embolden students to provide high quality written feedback, which increases their motivation and responsibility for learning (Trautmann, 2009). When students are supported as they construct texts via web-based reciprocal peer review, they are able to experience the processes of scaffolding, modelling, reflection, articulation, coaching, and exploration (Likkel, 2012). These six processes help students externalize and visualize their inner writing progressions so that they are able to observe and learn from as well as support peers in writing and making text revisions (Yang, 2011).

Design assignments to align assignment criteria, peer review criteria, and instructional goals. Ideally, instructional goals span multiple courses and expectations for student performance are consistently aligned and developed throughout those educational experiences (Boase-Jelinek, Parker, & Herrington, 2013). Make your expectations explicit and explain the criteria for a writing assignment to students by using rubrics as a means of defining assignment criteria to students. Descriptions of what constitutes different levels of performance deepens student understanding of the intent of criteria and helps them to provide better feedback to peers while they gain a better understanding of the learning goals (Timmerman & Strickland, 2008).

‘Folder’ Method of Peer Review

As demonstrated in previous research, the use of a manila or other type of folder will allow each student to take ownership of his/her prior and recent writing mistakes, serve as a portfolio, and provide some relief for the writing teacher in a real scholastic setting over a period of time (Goodwin, 2012). In this peer review method, the flaps of the folder contain lists that are used to track the student’s assignments, strengths, weaknesses, and writing ideas. This methodology assesses the reactions and progress of the student in order to determine the efficacy of the ‘Folder’ methodology as a means of improving the writing of both English-speaking and ESL/EFL students taking collegiate writing courses (Goodwin, 2012). This method is similar to the in-class double-student peer review method employed in this study in that both amalgamate the results of multiple peer reviews has acquired the necessary linguistic and academic skills for post-secondary education. The primary goal of this ‘Folder’ methodology is to help to track progress.

Research Methods

The research design elucidates the strategy used to integrate the various facets of the research project in a coherent and cohesive manner (Flick, 2011). For this research, the mixed method design was selected to help determine the efficacy and impressions held regarding the use of peer review to improve student writing. In this research, there are elements that quantitative or qualitative methods alone cannot provide answers to, which is why a collaboration of these methods was applied to the study conducted. Mixed method research is one of the three paradigms where quantitative and qualitative research approaches, techniques, and analysis are amalgamated in one study (Graziano & Raulin, 2009). According to Creswell (2009), the mixed method approach provides a better understanding of the research problem. Furthermore, the mixed method approach is used because it enables the researcher to examine the opinions, attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs of the research subjects through statistical quantification of the collected data.

Qualitative Research Strategy

Qualitative research consists of several procedures based on of various systemic questions relative to the selected topic designed to assist the researcher in gaining an in-depth understanding about the particular issue (Graziano & Raulin, 2009). According to theorists, qualitative research is not bound by adherence to pre-specified methods or a static hypothesis (Willis, 2008). Examining the use of qualitative research designs such as interviews, case studies, ethnographies, and historical research has shown that these methods explore essential interactions and are typified by a research paradigm that develops as the researchers understanding of the material progresses (Patton, 2008).

The benefits of the qualitative research process has encouraged the implementation of this method in the context of this study to enlist engaging data objectively while depicting detailed participant perspectives so that this research introduces a comprehensive understanding of their impressions (Babbie, 2007). Adapting the qualitative methodology present the greatest measure of clarity for the statistical analyses representing the data collected. This qualitative approach will examine existing research and literature to formulate a conceptual theoretical framework in which the research will be formatted.

Quantitative Research Strategy

A correlational non-experimental observational design is appropriate for this study because variables occur naturally and relationships among two or more phenomena can be explored. Quantitative research methodology is a systematic process using techniques to gather measurable data to develop new information about phenomena and investigate possible relationships. Quantitative research methodology uses deductive approaches following a linear path, which emphasizes explicit standardized procedures to measure variables and test hypotheses to form plausible relationships. The quantitative methodology was more suited for this study because correlational research examines and quantifies the relationship between variables using a numerical index. According to Creswell (2012) reviewing existing instruments for data collection allows researchers to select a current version that meets good validity and reliability scores. Descriptive statistical analysis will be calculated from the demographic information to describe trends and or make comparisons among the respondents.

Research Design

The use of the in-class double-student peer review process is a methodology constructed as an extension of the ‘Folder’ Method previously pioneered in classroom settings (Goodwin, 2012). I applied this methodology in the Freshman Composition 1 and Freshman Composition 2, as well as with Business Writing classes I have taught over a three year period. I had approximately 20 students per class teaching four classes per semester, which amounts to 24 classes, and 480 students. This constituted my sample population.

In this variation of the peer review stratagem, each student gave me their assignment at the beginning of the class. I randomly distributed the assignment to the class so that no student got their own paper. Each student was instructed to write his/her name in the top left-hand corner of their peer’s paper so I would know who reviewed the paper. The class was then allowed to spend time reading and writing comments/annotations on their peer’s paper with the directive to point out errors, suggest better ways of writing a sentence, give suggestions for flow enhancements, and propose corrections according to any current material discussed in class, (such as syntax, alliteration, tenses, topic clarity, or other relevant suggestions).

When the peer-reviewing session was complete, the peer reviewer returned the paper to its author so the student could review the remarks on the paper and discuss any comments with the peer reviewer that lacked clarity. If further elucidation is necessary, the teacher is called into the discussion so both the peer reviewer and author learn from the experience. During the peer-review sessions, I walked around the classroom facilitating the exercise and reading over shoulders to place my comments on the author’s paper during the peer-review session when I saw errors. The conference that the students have following the review process lasts about ten minutes to confirm the errors, see if the author agrees or disagrees with the peer-reviewers comments, and ensure comprehension of the results of the review. If the students do not agree, then, I am called to listen, to review and to teach.

Student Survey

At the end of each course every semester, I asked my students to complete and return a simple three question survey designed to gauge their impressions to determine the students’ perception of the benefits they have realized from the peer review methods used. The questions asked are organized in Table 2: Survey Questions, presented below.

Table 2: Survey Questions

| Survey Questions |

| Do you like peer reviewing? Why or why not? |

| Did peer reviewing improve your English ability in writing?

If yes, why; if no, why not? |

| Do you feel stronger in your writing abilities?

If yes, why; if no, why not? |

In total, 480 surveys were returned, although all three questions were not always fully answered. Negative and biased terminologies are excluded from the questionnaire to avoid misinterpretations or biased results (Babbie, 2007). The compiled results are recorded in Table 3: Results of Survey located in the Research Methods section.

Ethical Considerations

Research ethics necessitate respect for those indirectly or directly involved in the research. The current research has complied with all relevant codes of ethics during the course of the secondary and primary investigation (Graziano & Raulin, 2009). The respondents in the primary investigation were truthfully acquainted with the purpose, nature, and mode of execution of the study, as well as how the findings would be processed and reported. Informed consent of the participants was granted. The welfare and interest of all the directly or implicitly associated respondents and the establishment were taken into consideration. Furthermore, participant privacy was respected and subjective data interpretations were avoided to maintain the integrity of the participant/researcher relationship (Flick, 2011). The collection, treatment and disclosure of the accumulated data or information was performed according to all relevant statutes, with careful consideration given to research ethical implications with regard to the economic, political, communal, and psychological consequences of this work.

Results and Discussion

This section will first present the results of the surveyed students regarding their impressions of their learning experience using the in-class double-student peer review process in my Freshman Composition 1, Freshman Composition 2, and Business Writing classes. The results will be presented in the form of tables and graphs to illustrate the research findings. Following the presentation of the results, a discussion of the determinations that can be drawn from these results will ensue. The discussion will also categorically debunk each con associated with peer review that was presented in the Cons of Peer Review section of the Literature Review using accepted parallel research to support the validity of the findings.

Results of In-Class Double-Student Peer Review

The summative results of the student surveys collected are presented in Table 3: Results of Survey, which illustrates the aggregate responses for each question asked in the questionnaire and a compilation of the most common responses received from the students.

Table 3: Results of Survey

| Question | # of Students | Responses |

| Do you like peer reviewing? Why or why not? | 360 | Stated yes, as they could show the author of the paper their mistakes and most of the time, they knew why the mistakes were made. |

| 100 | Stated no, as they did not believe that it helped them in any way | |

| 20 | Did not answer the question completely. | |

| Did peer reviewing improve your English ability in writing? If yes, why; if no, why not? | 377 | Stated that they knew that it improved their English ability, as their papers received fewer error marks from the professor and they made high grades. |

| 89 | Stated that they did not believe that it improved their English writing abilities as they continued to make low grades and some stated they did not write much on their peer’s papers. | |

| 14 | Did not answer the question completely. | |

| Do you feel stronger in your writing abilities? If yes, why; if no, why not? | 386 | Stated they felt stronger in their English abilities as they were able to write better, had improved comprehension, and their peer’s writing errors much easier to identify than in the past. |

| 83 | Stated that they were weak and maybe improved in some areas but still did not feel stronger in writing. | |

| 11 | Did not answer the question completely. |

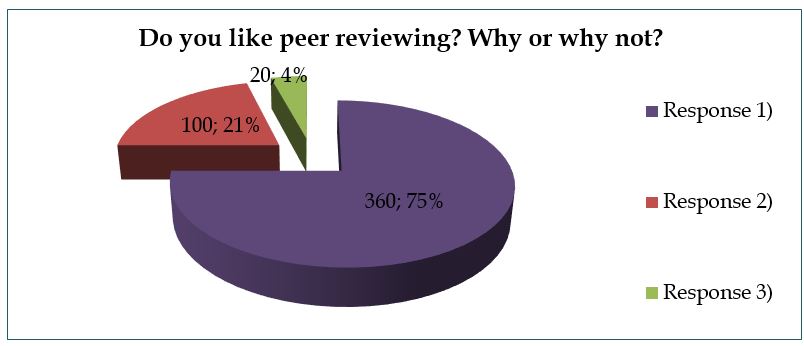

The individual results for each question in the survey are illustrated in Figures 2-4 and each response is represented according to the number for the respective question. The graphical illustration for the first question is presented in Figure 2: Results for Survey Question 1 presented below, where the section marked ‘Response 1’ correlates to the appropriate response in Table 3: Results of Survey for the answer to each question on every graph.

Figure 2: Results for Survey Question 1

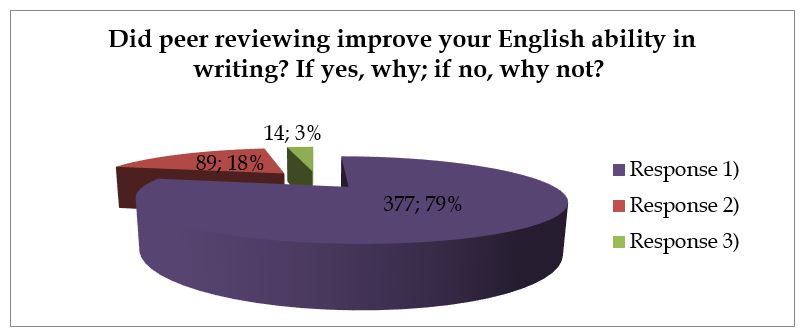

The graphical illustration for the second question is presented in Figure 3: Results for Survey Question 2 presented below.

Figure 3: Results for Survey Question 2

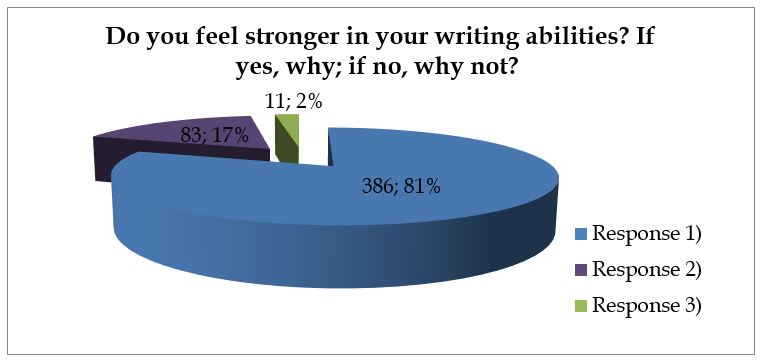

The graphical illustration for the third question is presented in Figure 4: Results for Survey Question 3 presented below.

Figure 4: Results for Survey Question 3

These aggregate results are analyzed in detail below in the Discussion of Results.

Discussion of Results

In direct response to the several cons illuminated in the part of the Literature Review hat discusses the Cons of Peer Review, this section will directly relate how the research, supported by current literature, debunks each negative claim regarding the efficacy of peer review as a learning strategy. The first perception mentioned stated that the inexperience of the students detracted from the ability of students to learn from the activity, but the student observations presented from the first research question showed that 75% of students stated that they felt they had learned from the experience. Although 21% were in agreement with the common rebuff that peer review was a waste of time and they did not benefit from the exercise, the majority of respondents related that they realized strong improvements in comprehension of the types of errors they were encountering and indicated that they were often able to locate errors and suggest corrections (Lundstrom & Baker, 2008).

The second question helps debunk the contention that students did not provide relevant feedback since 79% of the respondents indicated that they felt their writing abilities had grown stronger. However, 18% of the students answering this second question supported the critique that students did not comment sufficiently on their peers’ papers, even though the overwhelming majority responded in support of the author’s position and stated that their papers were evidently improved in that there were fewer errors, which resulted in better grades. This minority of 18% also stated that they continued to receive low grades on their writing assignments, but they also indicated that they did not typically make many corrections on their peers’ papers, suggesting poor outcomes due to lack of participation (Poschl, 2012).

The final research question presents evidence to debunk the contentions regarding that peer review does not improve the abilities of EFL/ESL students completely since 81% of the respondents indicated that they felt stronger in their English abilities, were able to write better, had improved comprehension, and their peer’s writing errors much easier to identify than in the past while an additional 17% stated that, although they were weak, they had improved in some areas, but still did not feel stronger in writing.

It is the belief of this author that these results do challenge the negative theories surrounding the merits of peer review. The results have shown that, while not all students know the answers and do miss errors; peer-reviewing is still beneficial even in these instances. In all instances where the students fully participate by providing relevant comments, everybody learns from the exercise, even the students that write very well. This methodology shows students exactly what is correct and not correct in writing genres, grammar, sentence structure, and flow of ideas even though the peer reviewer is not required to correct the errors, but point them out and the teacher can support the learning with feedback as well.

Realized Benefits of Peer Review

Several immediate benefits of peer review are that students are able to identify their peers’ errors prior to grading; they are able to recognize these same mistakes when they make them and improve their own writing; and it reinforces the rules associated with the mistakes their peers make (Bowman-Perrott, et al., 2013; Odom, Glenn, Sanner, & Cannella, 2009). However, one commonly stressed drawback of the peer review method is that students often indicate their peer reviewer did a poor job, which typically occurs when the reviewer is less advanced than their peer or is at the bottom of the grading scale due to lack of initiative (Lavy & Yadin, 2010). Despite the benefits mentioned, some possible problems encountered include:

- The student who reviewed the paper is weak or

- The student who reviewed the paper did not read the paper carefully.

Noting these two possible problems is why I have the peer-reviewers write their names in the top left-hand corner of the paper so that, if the paper is lacking good review, I can confront the peer reviewer privately to learn why. Additionally, two peer reviewers are used in this method because it is unlikely that the student will get two reviewers that do not review the paper well.

Linguistic, social, emotional, and cognitive development have been established as complimentary processes that work in concert Semantic development describes the technical aspect of knowledge acquisition and comprehension (Otto, 2010). Semantic knowledge deals with the relationships between words, objects, and the conceptual connection between the two, including how interrelated objects can be grouped together according to their similarities (Otto, 2010). Development of these aspects allows each person to form syntactic and morphemic understandings of word construction (Otto, 2010). Construction of these language dimensions facilitates the ability to analyze, gauge, and create new words while progressing to further stages of literacy and spelling while they develop the knowledge that even when pronunciation changes, the spelling often stays constant (Anderson, et al., 2001; Crim, et al., 2008).

It has been established that language learning is especially successful when the objective language is used to facilitate an understanding of the language overall and for the purpose of enhancing their reading or listening skills. To achieve this end, EFL/ESL educators encourage their students to participate vocally in language classrooms and produce intelligible feedback. Such involvement can help students establish a foundation that will enable them to accurately communicate what they want to say and can be the determining factor in whether they are able to say it. Furthermore, student “participation in verbal interaction offers language learners the opportunity to follow up on new words and structures to which they have been ex-posed during language lessons and to practice them in context” (Tong, 2010, p. 240). These factors can provide students with the motivation to learn and improve their conversational skills and behavioral patterns.

Reviews concerning the efficacy of pairing EFL students in groups to encourage oral participation found that when second language learners worked in groups, their motivation increased, they took more initiative, and experienced lower levels of anxiety regarding their learning (Lan, 2009; Wei, Brok, & Zhou, 2009). Overall, production can encourage learners to analyze input grammatically, with accuracy also increased by the negative feedback that verbal hypothesis testing elicits. When comments are available from every round of revision, as with the mentioned Folder Method; it significantly improves the outcomes of the peer review process because the author can review their work at each stage of the process to note deficiencies that can be improved or avoided in future writing (Goodwin, 2012; Pulverer, 2010).

Conclusion

Peer assessment is an integral and important component of the teaching and learning process for both educators and students. The powerful motivating effect of assessment on students is understood and tasks are designed to encourage valued study habits. There is a clear connection between expected learning outcomes, what is taught and learned, and the knowledge and skills assessed. Assessment tasks evaluate student’s abilities to analyze and synthesize new information as well as concepts rather than rote memorization abilities. The perpetual deficiencies in primary educational forums have nullified the conviction that a student’s ability to meet basic English entry requirements ensures that the individual has the fundamental writing skills for post-secondary education (Boase-Jelinek, Parker, & Herrington, 2013). The primary goal of this ‘folder’ methodology is to help to stimulate my students’ intrinsic motivation by allowing them to track and take responsibility for their own progress by increasing student autonomy, goal setting, and student reinforcement.

To be effective with increasing student achievement, district leaders and school personnel must collaborate to foster learning environments that encourage the development of high levels of self-efficacy for all participants (Anderson, et al., 2001). Higher efficacy beliefs correlate to increased student performance and the teacher must accept responsibility for implementing proven instructional strategies (Dai, 2010). The relationship between educator and student self-efficacy is vital to academic progress, instructional performance, and the development of a positive learning environments (Decker, Decker, Freeman, & Knopf, 2009). The use of in-class peer review encourages students to be enthusiastic about learning and writing, which is displayed through improved curricular demonstration (Barst, Brooks, Cempellin, & Kleinjan, 2011).

Limitations

Limitations provide clarity about potential weaknesses that may affect the study and usability of the results for future researchers to advance the findings into other situations (Cresswell, 2012). This study is limited in several manners. The first limitation is that the research was conducted on a small sample of students. This limited sample size may decrease the generalizability to a larger population because all areas of K-12 public education were not included, such as middle school and high school (Creswell, 2009). The next limitation is that a purposive sampling to collect data may not yield the desired participants from each category to measure appropriately and compare the results. Third, the study is dependent upon the survey respondents’ willingness to participant and answer honestly, which some did not. Furthermore, the disadvantage of using surveys is that researchers cannot manipulate the conditions under which the respondent completes the instrument, ensure completion, or expedite return times. It is also posited that social desirability bias affects the ability of researchers to obtain accurate answers because respondents may overstate an attitude or behavior to conform to social norms (Draugalis, Coons, & Plaza, 2008).

References

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P. W., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E., Pintrich, P. R., . . . Wittrock, M. C. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

Babbie, E. (2007). The Practice of Social Research (11th ed.). California: The Thomas Wadsworth Corporation.

Ball, J. (2010). Educational equity for children from diverse language backgrounds: Mother tongue-based bilingual or multilingual education in the early years. Canada: University of Victoria.

Barst, J., Brooks, A., Cempellin, L., & Kleinjan, B. (2011). Peer review across disciplines: Improving student performance in the honors humanities classroom. Honors in Practice, 7, 127-136.

Boase-Jelinek, D., Parker, J., & Herrington, J. (2013). Student reflection and learning through peer reviews. Issues in Educational Research, 23(2), 119-131.

Bowman-Perrott, L., Davis, H., Vannest, K., Williams, L., Greenwood, C., & Parker, R. (2013). Academic benefits of peer tutoring: A meta-analytic review of single-case research. School Psychology Review, 42(1), 39-55.

Brammer, C., & Rees, M. (2007). Peer review from the students’ perspective: Invaluable or invalid? Composition Studies, 35(2), 71-85.

Brill, J. M., & Hodges, C. B. (2011). Investigating peer review as an intentional learning strategy to foster collaborative knowledge-building in students of instructional design. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 23(1), 114-118.

Campbell, K., Combs, C., Kovar, S., Napper-Owen, G., & Worrell, V. (2009). Elementary teachers as movement educators (3rd ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Cresswell, J. (2012). Educational research: Planning, Conducting, and evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Crim, C., Hawkins, J., Thornton, J., Rosof, H., Copley, J., & Thomas, E. (2008). Early childhood educators’ knowledge of early literacy development. Issues in Teacher Education, 17(1), 17-30.

Dai, W. T. (2010). Examine the relations of perceived classroom environment to effectively and emotion regulation of students in Hong Kong.

Decker, C., Decker, J., Freeman, N., & Knopf, H. (2009). Planning and administering early childhood programs (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

Draugalis, J., Coons, S., & Plaza, C. (2008). Best practices for survey research reports: A synopsis for authors and reviewers. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72(1), 1-6.

Flick, U. (2011). Introducing research methodology: A beginner’s guide to doing a project. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Goldenberg, C. (2008, Summer). Teaching English Language Learners: What the research does-and does not-say. American Educator, 8-23, 42-44.

Goodwin, R. (2012). The ‘Folder’ methodology of improving writing. Arab World English Journal, 3(2), 148-167.

Graziano, A., & Raulin, M. (2009). Research methods: A process of inquiry (7th ed.). Boston, MS: Allyn & Bacon.

Hartberg, Y., Gunersel, A. B., Simspon, N. J., & Balester, V. (2008, February). Development of student writing in biochemistry using calibrated peer review. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 2(1), 29-44.

Hertzog, L. (2011). Can a successful ESL teacher hold deficit beliefs of her students’ home languages and cultures? Multicultural Perspectives, 13(4), 197-204. doi:10.1080/15210960.2011.616829

Huitt, W. (2011). Bloom et al.’s taxonomy of the cognitive domain. In Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Retrieved from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/cognition/bloom.html

Kao, G. (2013). Enhancing the quality of peer review by reducing student ‘free riding’: Peer assessment with positive interdependence. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(1), 112-124.

Kaufman, J., & Schunn, C. (2011). Students’ perceptions about peer assessment for writing: Their origin and impact on revision work. Instructional Science, 39(3), 387-406.

Lan, W. (2009). Chinese students’ perceptions of the practice of peer review in an integrated class at the university level. TESL Reporter, 42(2), 35-56.

Lavy, I., & Yadin, A. (2010). Team-based peer review as a form of formative assessment: The case of a systems analysis and design workshop. Journal of Information Systems Education, 21(1), 85-98.

Lawson, G. W. (2011). Students grading students: A peer review system for entrepreneurship, business and marketing presentations. Global Education Journal(1), 16-22.

Likkel, L. (2012). Calibrated peer review essays increase student confidence in assessing their own writing. Journal Of College Science Teaching, 41(3), 42-47.

Liu, M., & Chai, Y. (2009). Attitudes towards peer review and reaction to peer feedback in Chinese EFL writing classrooms. TESL Reporter, 42(1), 33-51.

Lundstrom, K., & Baker, W. (2008). To give is better than to receive: The benefits of peer review to the reviewer’s own writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 18(2009), 30-43.

Ma, J. (2012). EFL students’ decision-making and criteria use in peer review: Influence of teacher writing beliefs. English Teaching & Learning, 36(3), 87-131. doi:10.6330/ETL.2012.36.3.03

Moore, C., & Teather, S. (2013). Engaging students in peer review: Feedback as learning. Issues in Educational Research, 23(2), 196-211.

Nassaji, H., & Fotos, S. (2011). Teaching Grammar in Second Language Classrooms Integrating Form-Focused Instruction in Communicative Context. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis.

Odom, S., Glenn, B., Sanner, S., & Cannella, K. S. (2009). Group peer review as an active learning strategy in a research course. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 21(1), 108-117.

Otto, B. (2010). Language development in early childhood (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

Patton, Q. M. (2008). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publication, Inc.

Poschl, U. (2012, July 6). Multi-stage open peer review: Scientific evaluation integrating the strengths of traditional peer review with the virtues of transparency and self-regulation. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience, 6(Article 33), 1-16.

Pulverer, B. (2010). Transparency showcases strength of peer review. Nature, 468(7320), 29-31. doi:10.1038/468029a

Quible, Z. K., & Griffin, F. (2007, September/October). Are Writing Deficiencies Creating a Lost Generation of Business Writers? Journal of Education for Business, 32-36.

Sadker, D. M., & Zittleman, K. R. (2009). Teachers, schools, and society: A brief introduction to education [with CD and Reader] (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Samson, J. F., & Collins, B. A. (2012). Preparing all teachers to meet the needs of English language learners: Applying research to policy and practice for teacher effectiveness. New York: Center for American Progress.

Timmerman, B., & Strickland, D. (2008). Faculty should consider peer review as a means of improving students’ scientific reasoning skills. Journal Of The South Carolina Academy Of Science, 6(2), 1-7.

Tong, J. (2010). Some Observations of Students’ Reticent and Participatory Behavior in Hong Kong English Classrooms. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 7(2), 239–254.

Trautmann, N. M. (2009). Designing Peer Review for Pedagogical Success. Journal of College Science Teaching, 38(4), 14-19.

Wang, L. (2009). Chinese students’ perceptions of the practice of peer review in an integrated class at the university level. TESL Reporter, 42(2), 35-56.

Wei, M., Brok, P., & Zhou, Y. (2009). Teacher interpersonal behavior and student achievement in English as a Foreign Language classrooms in China. Learning Environmental Resources, 12, 157–174.

Willis, J. W. (2008). Qualitative research methods in education and educational technology. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Wilson, L. O. (2006). Beyond Bloom-A new Version of the Cognitive Taxonomy. Retrieved from Dr. Leslie Owen Wilson’s Curriculum Pages: http://www4.uwsp.edu/education/lwilson/curric/newtaxonomy.htm

Yang, Y.-F. (2011, July). A reciprocal peer review system to support college students’ writing. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(4), 687-700.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee