Industrial Management in Aviation, Research Proposal Example

Proposed Title of the Project

The title of the project is proposed as follows: “Policy and Adoption to a System: Lessons from SES”

Introduction

Air traffic management (ATM) is a key issue for research and innovation nowadays, since air transport demand is growing much more quickly than the airport systems’ capacity does, which creates a crisis in the modern commercial aviation in Europe (Wu & Caves, 2002). Ginieis, Sanchez-Rebull, and Campa-Planas (2012) has also recently supported this opinion by stating that both the passenger traffic and air cargo volumes are continuing to increase, thus creating the potential benefit for national and international airlines, and posing tension on the airports’ capacity limits. Therefore, to tackle the changing needs of customers in the aviation industry, the research and practitioner community should be able to understand all aspects of the air traffic management systems’ functioning, and to delineate the procedure of change that can be enacted for the improvement of the overall ATM capacity in the European air space.

As Amadeo and Odoni (2013) indicated, ATM increases its role in the airport operations, since mastering the ATM fundamentals promises the decrease of traffic overloads, excessive congestion, and extra costs caused by delays in scheduling. Therefore, to fit the complex demands of modern air traffic users, the airports adopt more complex and innovative ATM systems that are capable of accommodating the growing numbers of users with various requirements and characteristics; increasing safety as understood by both the public and mass media; combining the heterogeneous staff with the intricate automated computer networks; evolving at a pace of the rapid technological change; and reducing expenditures for the functions mentioned above (Amadeo & Odoni, 2013). Hence, managing the airport’s potential appears directly dependent on the ATM system’s management, which implies that any change in the airport’s operations presupposes both a managerial and an engineering change.

The change towards liberalization of air space took place in the USA in 1977, which opened additional opportunities for low-cost carriers; a similar situation occurred in Europe in the 1990s, which has also provided the fundamental change in the European aviation (Ginieis et al., 2012). Hence, since then, as Majumdar (1994) admitted, the key concern in the European commercial aviation has been the “adequate provision and allocation of aviation infrastructure in the liberalized market” (p. 165). With the growing number of passengers and cargo to be transferred by air, and with the increasing quantity of privatized airports worldwide, the awareness of the need for tighter and more aligned regulation for airlines, the air traffic control (ATC) industry, airports, and the logistics operators becomes evident (Charlton, 2009). Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify both managerial and engineering solutions to enhance the ATM in European airports, and to facilitate their progress towards a more flexible and inclusive provision of services.

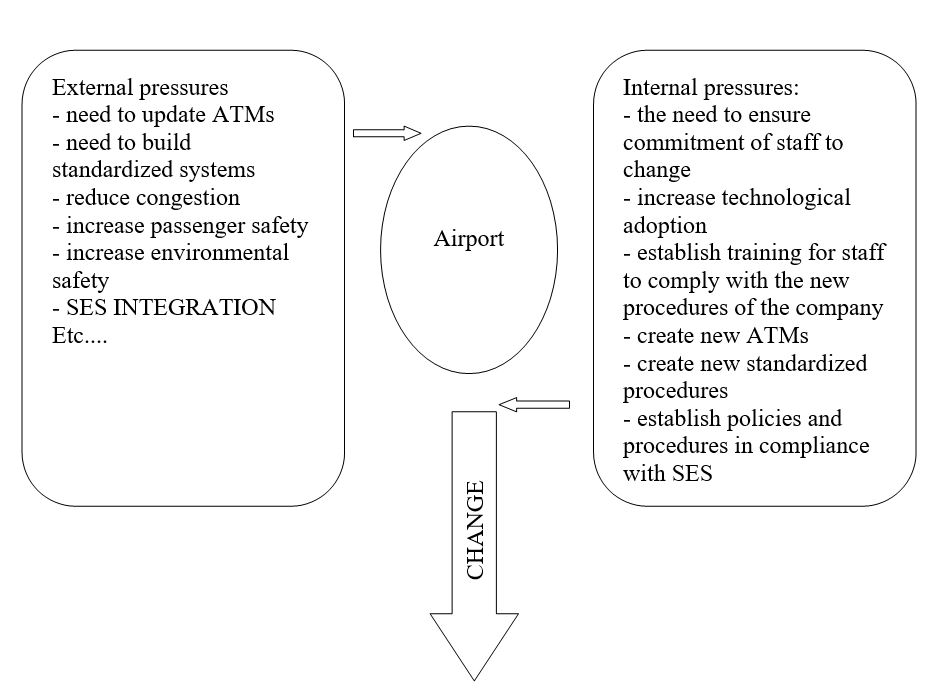

Management of innovation and change is a complex, lengthy, and demanding process that requires alignment of key objectives, the adoption of visible and measurable outcomes, and a set of milestones and deadlines according to which the change process is going to be undertaken. The project of interest in the present work is the adoption of the Single European Sky (SES) project by the European airports. The SES program emerged in response to the inability of the European airports to exploit their available capacity fully, which occurs mainly because of the non-aligned systems, lack of unified standards, and restrictive regulations precluding the national airports from moving towards cooperation.

Research Context

ATC problems started to reveal themselves since the earliest stages of the European air space liberalization, and were then confined to delays, congestion problems, non-alignment of ATM systems, outdated technology, fragmented and/or uncoordinated air flow control, etc. (Majumdar, 1994). Grushka-Cockayne and De Reyck (2009) provided evidence that not much has changed within 15 years in the European aviation, and the airport congestion is still a grave problem in many European airports. Moreover, the modern context of aviation operations is complicated by the focus on environmental concerns that preclude the promotion of capacity without the fundamental changes in the ATM systems (Grushka-Cockayne and De Reyck, 2009).

Obviously, to tackle the growing complexity and to manage the ATM problems in Europe, a comprehensive authority was appointed – the functions of reforming ATM, ATC, and other aviation-related issues lie on the EUROCONTROL institution (Van Houtte, 2000). EUROCONTROL has already achieved a certain progress in managing airports’ capacity, but there is an increasing consensus on the feasible potential of improvement only based on the intergovernmental cooperation and collaboration (Van Houtte, 2000). As a result of this awareness, a set of steps has been made to modernize and optimize the European ATM infrastructure, which is at present most exclusively targeted by the adoption of the SES program (Castelli & Pellegrini, 2011). The SES ATM Research Programme (SESAR) aims at modernizing the aviation infrastructure, and identifying the technological steps and priorities for implementing change into the key operations of the airports to achieve the workable and aligned common European air space.

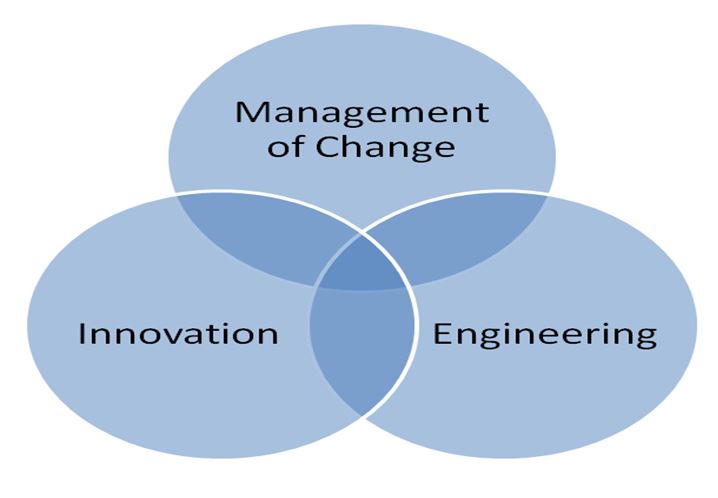

The key objective of the present project is to analyze the readiness of European airports to the adoption of SES and entering the aligned, technologically advanced, and modernized single European air space. To accomplish this objective, I will study the adoption of SES from the managerial perspective, as the management of change and innovation in an organization, and will assess the technical side of SES adoption. The practical aspect of research will accomplished by means of analyzing the potential of the Arlanda Airport (Sweden) for joining the Single European Sky (SES) project. Hence, taking into account that the research context combines the fields of management of change, innovation, and engineering issues in airports (in terms of reforming the decision support systems guiding the ATM), the major assumption underlying the present research is that SES adoption intersects the fields of management of change and innovation, and airport engineering.

Management of Innovation and Change

Change is an essential part of any organization’s development and improvement, and airports in Europe obviously need change to fit the innovative needs and demands of all stakeholders, as well as the changing context in which they have to operate. As Reiss (2012) admitted, “the essence of change management, as the totality of all the activities dealing with far-reaching changes, is to create a change-friendly context for all change processes” (p. 4). Hence, change management should be perceived as a complex of change activities and processes. The modern business environment requires a set of various aspects to be considered as vitally important in the optimal organization of change and innovation integration into the airports’ operation.

The need for a creative, non-standard approach to managing change has been understood more than two decades ago. As Wilmot (1987), Barczak, Smith, and Wileman (1987), and Michael (1982) noted, the change should be created, and not used as a response to the environmental pressures. However, change encompasses the adjustment of the organization to its environment, which is the key objective of any change and innovation – to meet the changing needs, requirements, and pressures more successfully, and to be able to meet raised organizational objectives. It is vital to take the employees’ emotions into account as well, since the organizational culture and the human factor of acceptance and non-acceptance of change often plays the key role in the change outcomes (Klarner, By, & Diefenbach, 2011).

According to Harrington (2006), organizational change management is aimed at minimizing the negative, disruptive impact of change on the organization. It is necessary to keep in mind that change is a process, and also a transitional process that implies moving the organization from one state to another one. However, in line with change, the airports adopting the SES requirements have to be aware of the need to introduce innovation as a creative process of generating ideas for practice (Lewis, 2011). There is no full-scale change without innovation, since innovation drives change due to external or internal pressures on the organization.

European Airports’ Management Challenges

All airports represent a “multi-service networked industry with significant monopoly control in the provision of many of its suite of services” (Reynolds-Feighan & Button, 1999, p. 113). Starting with the early 1990s, the levels of congestion in the European airports increased, which implied the insufficient capacity in the face of growing demand for air services. The liberalization that was undertaken in Europe through the implementation of the “Third Way” packages from 1993 to 1997 served an ever greater aggravator of decentralization and misalignment of the European airports’ coordination. Though a certain amount of control is still exercised directly and indirectly by the national governments, the majority of airports continue to experience air traffic control (ATC) problems across Europe. According to Majumdar (1994), the problems of ATC nature were related to the aviation infrastructure, which resulted in a high economic cost of inconsistencies – the peak periods rose by three times above their norm in 1986 for only two subsequent years, and only in 1988, Europe experienced 330,000 hours of the ATC-related departure delays. The average cost of those delays was roughly estimated at the level of US $970 million for airlines involved; the losses of passengers equaled about US $ 540 million; moreover, “routing network cost the airlines US $1.27 billion and the traveling public US $510 million, a combined total of US $1.8 billion in unnecessary cost in just one year alone” (Majumdar, 1994, p. 168).

Pricing policy of the European airports is at present one of the significant concerns affecting a wide range of long-term airport development indicators. According to Reynolds-Feighan and Button (1999), the pricing policy of any airport is of great significance, since it influences the economically meaningful allocations of capacity the airport possesses, and also determines the possible capacity extensions. Therefore, the pricing policy aspect is significant in determining the average size of an airport, the importance and emphasis on the long-term, short-term, and medium-term services, which directly and indirectly affects the whole EU infrastructure and traffic distribution (Reynolds-Feighan & Button, 1999). Hence, there is a need to focus on the pricing policy as an indicator worth close attention in introducing and managing change and innovation in the European air space.

Hence, as one can see, delays and extra costs, lack of collaboration in the segmented European aviation, and a lack of a comprehensive framework for managing change, innovation, and more efficient and optimized networking emerge as the key problems of the European airports faced even nowadays, despite the growing digitization, technological progress, and technology adoption in the European and worldwide aviation. Research and practice stand side by side in aviation, so it is also necessary what emerging challenges have been identified by the research community. According to the recent review of Ginieis et al. (2012), the key topics emerging and recurring in the European aviation research include airports (taxes, infrastructures, internal operations, etc.), alliances (agreements and planned coalitions for optimizing cooperation), costs (direct and indirect costs, accounting, capital costs, etc.), environment (the impact of aviation on the environment, and search for more eco-friendly technologies), finances (capital structure, productivity and profitability of airports, etc.), management (ATM, air traffic, industrial policies, crews, etc.), models (air transportation calculations and research), networks, passengers and safety, and regulation. Hence, particular attention in research and aviation management should be paid to these aspects.

Single European Sky (SES)

As it has been noted by Castelli and Pellegrini (2011), the Single European Sky ATM Research Programme (SESAR) is targeted at the modernization of ATM infrastructure, and the identification of steps and priorities for the optimization of the air space. According to Graham, Papatheodorou, and Forsyth (2010), the term “Single European Sky” is used to denote the set of measures to meet the needs for increasing capacity and air safety. The SES concept encompasses civilian and military sectors, and refers to the complex of “regulatory, economic, safety, environmental, technological, and institutional aspects of aviation” (Graham et al., 2010, p. 70). The SES paradigm targets the way of organizing the ATM procedures in Europe that has remained unchanged since the 1960s, and moving towards eliminating the intensifying congestion in the European airports.

The SES initiative is considered an effort to fundamentally transform the way air transport is organized and managed across Europe. The achievement of core principles and objectives of SES is aimed by introducing the sustainable and better functioning aviation; however, taking into account the unique network and gate-to-gate approaches, the SES project is expected to transcend the borders of the EU, and encompass a much wider aviation space in the Eurasian continent and beyond (Crespo & de Leon, 2011). Van Houtte (2000) underlined that the SES philosophy lies on the following pillars: presence of a strong regulator of aviation in Europe, consistency of regulation across Europe, perception of airspace as a common resource, management of SES in phases, access to air space for all users (commercial, general, and military aviation), active involvement of air traffic controllers in the reform, and the enhancement of the SES system by the air traffic service providers and users.

In 2004, the European Parliament and the Council adopted the Regulation 549/2004 to target the new ATM design presupposed by the SES framework. According to this Directive, the SES design was to be created by December 1, 2004. The core focus of the SES framework was thus to create the “common transport policy” that presupposes the “efficient air transport system allowing safe and regular operation of air transport services, thus facilitating the free movement of goods, persons and services, with beneficial consequences as regards air traffic delays and growth” (Graham et al., 2010, p. 70).

Key Airport Capacity Indicators for Management of Change in Aviation

To identify the key productivity indicators that will guide the analysis of airports’ readiness to integrating the SES project, one has to understand what the airport capacity concept represents. According to Reynolds-Feighan and Button (1999), airport capacity denotes “the ability of a component in the airport system to handle aircraft and is usually expressed in terms of operations per hour” (p. 116). Moreover, it is notable that the capacity of an airport to perform a certain number of operations per hour depends on the following factors: ceiling and visibility, air traffic control, aircraft mix, and nature of operations (Reynolds-Feighan & Button, 1999). Hence, one should keep in mind that the airport capacity is a measure of supply.

It is also necessary to keep in mind the effect of delays on the airport capacity. As Reynolds-Feighan and Button (1999) admitted, the delays in airports can be caused by “internal airline problems or schedule discrepancies, passenger and baggage, cargo and mail, aircraft and ramp handling, technical and aircraft equipment, damage to aircraft and EDP automated equipment failure, flight operations and crewing, weather, airport and government authorities, reactionary, and miscellaneous” factors (p. 117). Hence, the perception of air capacity in any airport has to be coupled with the detailed analysis of delays and their nature.

Taking into account the lack of capacity utilization in European airports because of the systems’ segregation and standardization, one can assume that the level of key systems’ standardization can be accepted as a key indicator of the airport’s capacity, before and after change (Grushka-Cockayne & De Reyck, 2009). Since SES targets the elimination of the aviation system’s fragmentation, the extent to which the pan-European, SES-related structures and systems are embedded in every separate airport’s functioning can be used as the key indicators of the airports’ capacity. Standardization presupposes more efficient communication, which is of key importance for SES integration.

Since the ATM system’s efficiency is stressed as the critical component affecting the capacity of both every individual airport and the overall aviation network, one has to keep in mind the number of components that should be critically assessed when evaluating the ATM systems, according to De Amadeo and Odoni (2013). These components include the ATM’s procedures and regulations, the organization of airspace, the human air traffic controllers, the automation systems, the communications, surveillance, and navigation systems according to which the quality of ATM can be assessed. It is also necessary to critically assess the advanced air traffic flow management (ATFM) systems that are used in the USA and Europe for preventing the overload of airports and ATM facilities, as well as minimizing the economic and other penalties resulting from air traffic congestion (De Amadeo & Odoni, 2013). The ATFM systems are more centralized in Europe, and perform the functions of predicting the location of potential overloads, developing strategies for overload relief, and overseeing the implementation of those strategies in real time (De Amadeo & Odoni, 2013). Judging from all aspects of airport capacity and SES requirements, one can assume that the choice of KPIs should be made in favor of KPIs that can be used to measure the quality of ATM infrastructure, the increased capacity, air safety, and reduced congestion, as well as a new liberal regulatory policy according to which the transition from the airspace monopoly to a liberal and pluralistic, democratic, but aligned SES can be provided. Upon review of the article by Hall (2009) who stated that the KPIs for a successful change should be chosen in regard to performance, culture, and fiscal issues, the following set of criteria for analysis was chosen:

Table 1. KPIs Chosen for Analysis of Airports’ Readiness for SES Integration

| KPIs for measuring performance and capacity |

|

| KPIs for measuring the fiscal aspects of airports’ efficiency |

|

| KPIs for assessing the airports’ readiness for SES adoption | · ATM systems’ efficiency and cost

· Standardization of automation, communication, surveillance, and navigation systems · Environmental impact factor · Air safety measures · Regulatory changes · Congestion reduction measures |

The choice made for the present KPIs was dictated by the need to assess the overall performance of any airport getting ready for the adoption of SES for the sake of building a sound basis for understanding its strengths and weaknesses, areas that are already ready for integrating SES, and areas needing further improvement for the SES change to succeed. As for fiscal aspects of airports’ efficiency, the financial aspect of organizational functioning is always indicative of the organization’s success. In case the financial data are strong and positive, the organization can introduce an innovative change; however, in case the organization is weak financially, one has to think of mitigating the financial problems first, and then passing on to the change introduction. Finally, the SES-related KPIs were chosen in compliance with the works of Castelli and Pellegrini (2011), Graham, Papatheodorou, and Forsyth (2010), and Van Houtte (2000) who stated that the SES aim is to modernize the ATM infrastructure, so the efficiency of ATM may be perceived as the key indicator of SES readiness. Moreover, the objectives of SES are delineated as increasing capacity and air safety, reduction of congestion, and introduction of strong regulation. Hence, these aspects have been chosen as KPIs illustrative of the extent of success with which an airport has implemented, or is ready for implementing SES requirements.

Research Objective

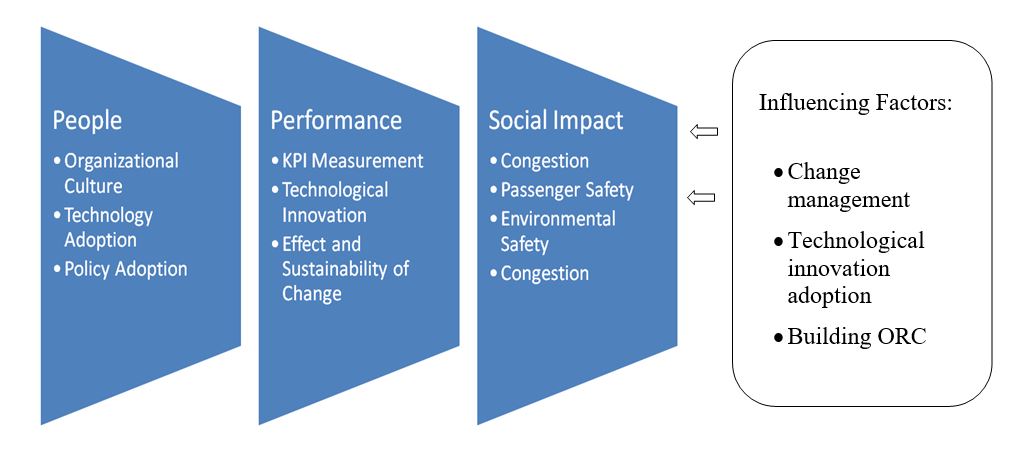

Taking into account the key fields and concepts related to the presently chosen research topic, I have decided to focus on the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) according to which the effectiveness of the airport’s integration of SES standards can be assessed. The technological complex of airport operations and their interconnected and mutual impact that create the airport operations outcomes will be researched for the sake of identifying the key operational variables that should be targeted to increase the airport capacity, thus making the European airports more ready for SES implementation. It is obvious that the adoption of SES requirements is concerned with managing change and innovation; hence, the prime research focus will be distributed among three fields of research:

The underlying assumption guiding the present research is that there are specific KPIs that have to be improved specifically for the integration of SES standards, and which improve the overall capacity of the airport. Consequently, the wide objective of the present research is to study the requirements for SES and its critical success factors, to identify the KPIs that generally affect the airports’ capacity, and to assess the extent to which SES requirements are feasible for European airports in the plain of conducting managerial change and innovation.

Research Questions

The central research question of the project is:

“How can management of innovation and change to SES in an airport be handled?”

The narrower sub-questions elicited for the purpose of the present research include:

- What are the root causes and requirements for SES?

- How successful has the Arlanda airport been so far in the adoption of SES?

- What are the key managerial challenges in the SES adoption?

- What are the limitations to interoperability of SES in airports?

The first research question will be answered by means of conducting a thorough literature research and document analysis on the regulations existing before SES, and the regulatory path that the European airspace control authorities went through to work out the SES initiative. The cornerstones of SES will be delineated in proper regard to the ways in which they can be practically incorporated in the real-life settings of European airports. After these data have been generated, the findings on research question one will be tested empirically on the real-life example of the Arlanda airport in Sweden; the airport’s readiness for incorporating SES will be tested in the form of the case study, and statistical data on elicited KPIs will be gathered and discussed to answer research question two. Naturally, it is expected that the Arlanda airport will show strengths not in all SES-related KPIs, and the third research question will be answered in the form of continuing the analysis of SES readiness and challenges that have to be overcome by the Arlanda airport for adequate integration of SES requirements and policies. These findings will be further generalized with proper reference to theory of airport management to answer research question four related to the challenges that need to be overcome by European airports in general for managing change and SES adoption successfully.

Research Methodology

The present research will utilize both the deductive and inductive types of research, mainly because the initial theoretical inquiry is based not on a clearly formulated hypothesis, but on the search for theory and hypothesis that would further on guide the study onwards. As Gratton and Jones (2010) indicated, when the researcher wants to study something under-researched, it is better to use the inductive approach to the study, since it helps to become … The major challenge in conducting the inductive research is usually seen in the lack of time and resources, but the present project is a long-term one, so I took the risk of initiating the inductive study. The focus of the inductive research is on the generation of explanation of a certain phenomenon of interest based on the data collected, in contrast to the deductive approach that aims at testing the pre-determined theory (Gratton & Jones, 2010).

Blaikie (2009) also offered the distinct classification of the inductive and deductive research, stating that the inductive type of research takes the form of generalizations and networks of propositions. It also uses the abstract models verified with the help of mathematical representation (Blaikie, 2009). The deductive research is conducted with the help of hypothesis production by deductive argument, and their testing by matching against data (Blaikie, 2009). However, taking the present approach is impossible in the present field of interest, since SES is still a project under way, and it is not completely integrated in the European aviation. Hence, there is no ability to test the hypothesis against the collected data, with the only opportunity of making propositions and testing them on the basis of the technological implications and performance progress measurement.

The first research question will be answered qualitatively by means of gathering data through literature review and document analysis; data about SES. The prime focus will be made on how evolution in adaption of regulations was handled in air transport, the pressures that made the European authorities formulate SES regulations, what research contribution has already been made by the SESAR program, and how these achievements have been put into practice by some European airports.

The second research question will be answered by means of applying the method of analyzing the key chosen KPIs for the analysis of the Arlanda airport’s progress in the adoption of SES requirements. The strategy of answering this question is to use the KPI data about the Arlanda airport for the past 8 years, starting from 2004, the time of SES strategy formulation, which is likely to show the evolution of capacity, safety, environmental impact, ATM costs, adoption of new technologies, etc. in this particular airport on the way to SES. The present findings will be highly valuable from the technical viewpoint of increasing the Arland airport’s compliance with SES, and thus ensuring its joining the SES program.

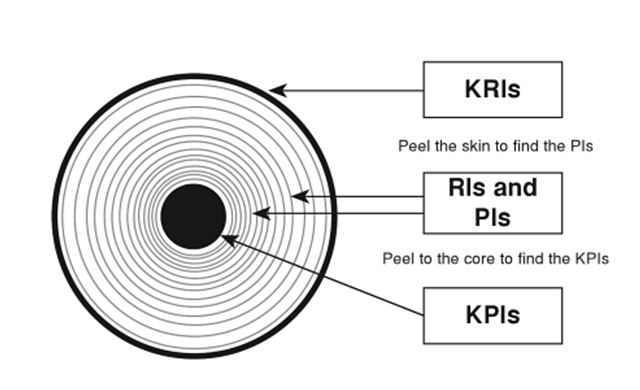

The quantitative data used for the present research will be collected from internal airport documents and reports to measure the success with which SES was implemented, and to which extent the KPIs for SES were improved. According to Parmenter (2012), the key performance indicators (KPIs) tell the organization’s management what to do to increase the performance dramatically. There is a diversity of performance measures that should be distinguished for the sake of realistic evaluation of KPIs, and understanding of the ways in which performance can be affected. Thus, as Parmenter (2012) admitted, there are key result indicators (KRIs), result indicators (RIs) and performance indicators (PIs), and the key performance indicators (KPIs) in the process of performance measurement – see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Four Types of Performance Measures

Source: from Parmenter (2012, p. 72).

Parmenter (2012) also summarized the key characteristics of KPIs: they are usually non-financial measures, are measured frequently, are controlled by the CEO and senior management, indicate what action is required from the staff, and have a significant impact on the organizational operation. They are also capable of encouraging proper action in the proper direction. Hence, the KPI methodology in the present research refers to the identification of KPIs as viewed by the SES introduction and policy documents that airports have to comply with to achieve full-scale SES adoption. Further on, the performance measurement of the Arlanda airport will be conducted according to the chosen KPIs, with the goal of identifying the goal-oriented and sensible KPI portfolio in aviation specifically for SES adoption, and to identify potential strengths and weaknesses in their adoption by European airports (Müllner, 2007).

The third research question will be answered by applying the method of case study to the Arlanda airport’s SES adoption process, and interviews with Arlanda Airport experts regarding the SES standards’ implementation. According to Yin (1994), the case study research represents “an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident” (p. 13). Woodside (2010) added that the inquiry made with the help of case study focuses on the description, understanding, prediction, and/or control of an individual, a process, an organization, etc. The core feature of a case study is the focus of the research issues on the object of the research (Woodside, 2010), which ensures the close investigation with a proper amount of feasible, detailed inferences upon the completion of the research endeavor. Hence, the case study and interviews are likely to give the managerial perspective on SES adoption.

The fourth research question will be answered by means of synthesizing the findings from research question two and three, and correlating them with the theoretical evidence found when answering research question one. The analysis of Arlanda airport’s initiatives and activities for SES adoption is likely to reveal both strengths and weaknesses of that process, which will give an opportunity to make conclusions about the challenges to interoperability that prevent many European airports from joining SES.

Significance of Research: Contribution to Theory and Practice

The significance of the present research is explained by its multi-disciplinary perspective; in viewing a European airport as a system of systems, I approached the adoption of SES as a set of managerial and technological requirements that pose a diverse range of constraints on the systems’ operation from the viewpoint of procedures, processes, and people. The change is inevitable and vitally necessary, as indicated by Grushka-Cockayne and de Reyck (2009), since not much change has been evident in the field of the European aviation within the past 15 years and even more, and the current European aviation is not able to cope with the growing volumes of passenger and cargo transferred by air, as well as with the innovative technological challenges and changes. Therefore, there is a need to ensure a smooth and effective transition towards SES in all European airports for the sake of creating a functioning, safe, and aligned aviation system in Europe.

Taking this practical need into account, I have decided to approach the adoption of SES from two problematic perspectives – managerial and technical one. To assess the extent of technological adoption of SES, I use the KPI methodology that has proven highly successful in guiding the organization towards the productivity increase, which is the prime goal of the SES project (Castelli & pellegrini, 2011; Graham et al., 2010; Hall, 2009). The choice of KPIs focused on the key objectives of SES enables to generate a concise methodology for evaluating SES compliance over time in any airport.

Moreover, there is a need to keep in mind that organizations primarily consist of people representing their key strategic assets; hence, any change should be accompanied with effective work of change agents and change teams striving to increase the willingness to change, commitment to change, establish readiness to change and technology adoption, and to promote change in the organizational culture. The change in an organization of any size and complexity can occur only in case the staff comprising it is involved in the change and accepts it. Hence, the analysis of SES adoption from both the managerial and technological perspective is likely to give an additional insight into the strengths and weaknesses of modern airports on the way to incorporating SES. The findings of the present research will possess both practical and theoretical significance; on the one hand, they will provide a workable methodology for assessing the progress of any airport in the SES adoption and challenges it has to overcome. On the other hand, the research will unite the managerial and technological perspectives on organizational change in a single theoretical framework, which is highly useful for change management theory, especially in terms of evaluating the impact of change, the outcomes of change, and the ways of mitigating barriers to change.

Theoretical Framework

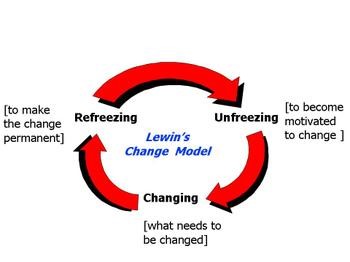

The key theories considered within the framework of the present paper stem from the key objectives thereof: assessing the readiness for change in an airport, managing change in the airport, and evaluating the barriers to change. Airports are complex structures that play a key role in the airspace infrastructure, and the contemporary European airports represent fragmentation and isolation in regard to other airports in contrast to the attempts to unify the European airspace, and to introduce the unitary regulation and system optimization. Hence, the theoretical perspective focuses on the organizational readiness for change (ORC), management of change, and mitigation of barriers to incorporate change into the organizational culture. The present concepts are compliant with the Lewin-Schein theory of change presupposing three stages: unfreezing, change, and refreezing.

Figure 2. Lewin-Schein Theory of Change

Source: from Change: So Hard to Do (2008)

Organizational Readiness for Change (ORC)

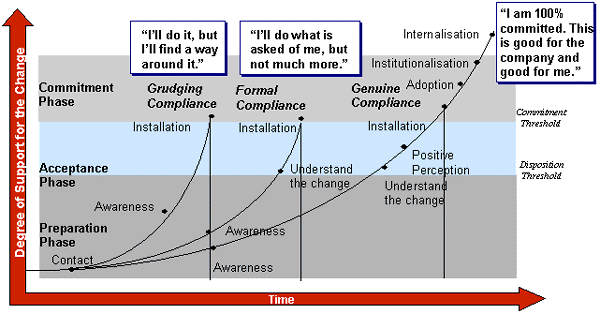

Organizational readiness for change (ORC) is a vital criterion that predetermines the success of change planned in any organization. Hence, it is necessary to keep such aspects as motivational readiness, training needs, and openness to innovation in both people and the organizational systems as the indispensible elements preceding change (Saldana, Henggeler, & Rowland, 2007). Moreover, organizational readiness for change is one of the central determinants of building commitment to change, which is also vital for the change to succeed.

Figure 3. Building Commitment to Change

Source: from Donnan (2006).

It is also necessary to keep in mind that assessing organizational readiness for change gives empirical data on the strengths and weaknesses, challenges and opportunities that the organization is likely to face during change, which is strategically important for the successful introduction of the organizational change at all levels.

Change Management and Technology Adoption

Change management and technology adoption are the key theoretical concerns of the present project, since SES requirements are centered around the key dimensions of updating the ATM systems and adopting more standardized surveillance, communications, and other systems, which all involves the adoption of the technological change. As indicated by Son and Han (2012), the technology adoption process is highly dependent on the technology readiness of the organization, which suggests that the proactive approach to training staff, communicating the need for change, and establishing workshops, discussion meetings, and consultation services for employees are vital for ensuring the successful transition of any airport towards SES adoption. Moreover, there is an indicator of technology adoption propensity (TAP) as noted by Ratchford and Barnhart (2012); the present factor depends on factors contributing to (optimism and proficiency) and hindering (dependence and vulnerability) the adoption of the technological change. Hence, the extent to which employees understand the technological change and are committed to it often predetermines the extent to which they are likely to adopt it, and use it in their daily work-related activities.

Adoption of technological change is also a change process; hence, it should be adequately managed. The SES adoption policy presupposes both a change in technology used, and in practices executed in the airports. Hence, a comprehensive change management approach and a feasible management model are necessary for guiding the change efficiently in the right direction. Since the Lewin-Schein model of change has been chosen, it is necessary to pay more attention to the intermediary, transition phase that also requires a model to bring the organization to the desired outcome of change. As Goodstein and Burke (1991) offered in their article, the model of Richard Beckhard and Reuben T. Harris is highly effective to administer the transition of the organization in that phase. The authors offered to assess the current state of the entity, and to identify the desired future state. Afterwards, the transition can be executed by means of using any method delineated below:

- Setting up a training program providing staff with skills necessary for the changed organization

- Modifying the organizational structure, redefining the jobs and work procedures

- Conducting a survey to identify the organizational culture, and to plan the organizational change at all levels

- Collecting data from staff on the desired changes, and implementing those changes in response to their feedback (Goodstein & Burke, 1991).

Hence, as one can see, the technology adoption should also be specifically guided within the framework of the organizational change, and SES adoption requires the change in both technology and procedures, which makes the change management of SES adoption a multi-dimensional task.

Conceptual Model

References

Alonso-Almeida, M. d. M., & Rodriguez-Anton, J. M. (2011). Organizational behavior and strategies in the adoption of certified management systems: an analysis of the Spanish hotel industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 19, pp. 1455-1463.

Blaikie, N. (2009). Designing Social Research. (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Polity.

Castelli, L., & Pellegrini, P. (2011). An AHP analysis of air traffic management with target windows. Journal of Air Transport Management, 17, pp. 68-73.

Charlton, A. (2009). Airport regulation: Does a mature industry have mature regulation? Journal of Air Transport Management, 15, pp. 116-120.

Crespo, D. C., & de Leon, P. M. (2011). Achieving the Single European Sky: Goals and Challenges. Frederick, MD: Kluwer Law International.

De Amadeo, R., & Odoni, R. (2013). Airport Systems Planning, Design, and Management. (**).

Donnan, S. (2006). Change Readiness. Metavolution. Retrieved from http://www.metavolution.com/rsrc/articles/change_readiness.htm

Ginieis, M., Sanchez-Rebull, M.-V., & Campa-Planas, F. (2012). The academic journal literature on air transport: Analysis using systematic literature review methodology. Journal of Air Transport Management, 19, pp. 31-35.

Goodstein, L. D., & Burke, W. W. (1991). Creating Successful Organization Change. Dynamics, 19(4), pp. 5–17.

Graham, A., Papatheodorou, A., & Forsyth, P. (2010). Aviation and Tourism: Implications for Leisure Travel. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Gratton, C., & Jones, I. (2010). Research Methods for Sports Studies. (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Grushka-Cockayne, Y., & De Reyck, B. (2009). Towards a Single European Sky. Interfaces, 39(5), pp. 400-414.

Harrington, H. J. (2006). Change Management Excellence: The Art of Excelling in Change Management. Chico, CA: Paton Professional.

Lewis, L. K. (2011). Organizational Change: Creating Change Through Strategic Communication. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Majumdar, A. (1994). Air traffic control problems in Europe: Their consequences and proposed solutions. Journal of Air Transport Management, 1(3), pp. 165-177.

Müllner, A. (2007). Calculating the Influence of Improvement Measures on Corporate KPIs. Norderstedt, Germany: GRIN Verlag.

Parmenter, D. (2012). Key Performance Indicators for Government and Non Profit Organizations: Implementing Winning KPIs. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Ratchford, M., & Barnhart, M. (2012). Development and validation of the technology adoption propensity (TAP) index. Journal of Business Research, 65, pp. 1209-1215.

Reiss, M. (2012). Change Management: A Balanced and Blended Approach. Norderstedt, Germany: Books on Demand.

Reynolds-Feighan, A. J., & Button, K. J. (1999). An assessment of the capacity and congestion levels at European airports. Journal of Air Transport Management, 5, pp. 113-134.

Son, M., & Han, K. (2011). Beyond the technology adoption: Technology readiness effects on post-adoption behavior. Journal of Business Research, 64, pp. 1178-1182.

Tanner, R. (2011). Leading Change (Step 2) – Create the Guiding Coalition. Management Is a Journey. Retrieved from http://managementisajourney.com/2011/01/leading-change-step-2-create-the-guiding-coalition/

Van Houtte, B. (2000). Towards a Single European Sky: Initiatives by the European Commission to reform Air Traffic Management. Air and Space Europe, 2(5), pp. 24-27.

Woodside, A. G. (2010). Case Study Research: Theory, Methods, Practice. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Wu, C.-L., & Caves, R. E. (2002). Research review of air traffic management. Transport Reviews, 22(1), pp. 115-132.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee