The Care of Post-Gastric Bypass Patients, Capstone Project Example

Abstract

The objective of this work in writing is to examine how nurse practitioners need to care for patients that have had gastric bypass in the past. Specifically examined will be what to look for, labs to test and how to analyze the results, follow-up testing, psychological and nutrient support needed and medications to prescribe to these patients. Examined as well will be the effect of trace mineral and vitamin deficiencies, and how to identify these by the signs and symptoms presenting in the patient.

Objective

The objective of this paper is to examine how nurse practitioners need to care for patients that have had gastric bypass in the past. Specifically examined will be what to look for, labs to test and how to analyze the results, follow-up testing, psychological and nutrient support needed and medications to prescribe to these patients. Examined as well will be the effects of trace mineral and vitamin deficiencies and how to find them in terms of signs and symptoms.

Introduction

There is a reported increase in the number of patients having bariatric surgeries each year and the increase in knowledge and skills needed by the nurse practitioner in providing care to morbidly obese patients following surgery. The number of bariatric surgeries performed in the U.S. “has recently increased 10-fold, from 14,000 in 1993 to an estimated 140,000 in 2004.” Nurses who provide care to bariatric-surgery patients “must demonstrated clinical skills for safe, efficient, and quality care during the post-operative period. ” (Drake, et al, 2009) The malabsorptive procedure is one in which decreased absorption of nutrients is induced through “shortening the functional length of the small intestine, so that the body absorbs fewer calories.” (Indian Women’s Health, 2011) The Restrictive procedure has as its objective the reduction of the stomach size through surgery, which thereby results in a limitation on the intake of food, and reduction on the feeling of hunger felt by the individual. (Indian Women’s Health, 2011, paraphrased) The combined restrictive/malabsorptive procedure is a combined operation using both restriction and malabsorption. (Indian Women’s Health, 2011, paraphrased) There are reported to be three types of gastric bypass treatment including those as follows:

- Gastric Restrictive Procedure;

- Malabsorptive Procedure; and

- Combined Restrictive and Malabsorptive Procedure. (Wittgrove, 2011)

The benefits of the Gastric Restrictive Procedure are the reduction in the amount of well-chewed food entering and passing through the digestive tract in the usual order. This enables the vitamins and nutrients along with the caloric content to become absorbed completely into the body. (Wittgrove, 2011)

Wittgrove (2011) reports that the Malabsorptive Procedure are operations that result in patient satisfaction at a high percentage and that serve to result in the greatest amount of weight loss stated at 74% at one year, 78% at two years and 81% at three years. Four years is stated at 84% with five years stated at 91%.

The Combined Restrictive and Malabsorptive Procedure is stated to result in more weight loss than the restrictive procedures.

Included in the risks associated with bariatric weight loss procedures are the following stated in the work of Wittgrove (2011):

- death;

- injury to intestines, stomach which may need repair;

- Rupture of stomach pouch;

- Injury to spleen resulting in possible removal;

- Blood clots, pulmonary emboli;

- Stroke;

- Anemia;

- Hemorrhage;

- Disruption of the incision;

- Pneumonia;

- Abscess (external and intra-abdominal) and wound infections;

- Heart attack;

- Bowel obstruction

- Hypoproteinemia;

- Vitamin requirements;

- Edema

- Incisional hernia;

- Leakage from anastomosis;

- Hair loss;

- Peptic ulcer;

- Kidney stones;

- Incision hernia;

- Leakage from anastomosis;

- Kidney stones

- Blood transfusion with possible reaction;

- Complications from anesthesia;

- Strictures or stenosis

- Possible emotional disorders, including depression; and

- Novel complications. (Wittgrove, 2011)

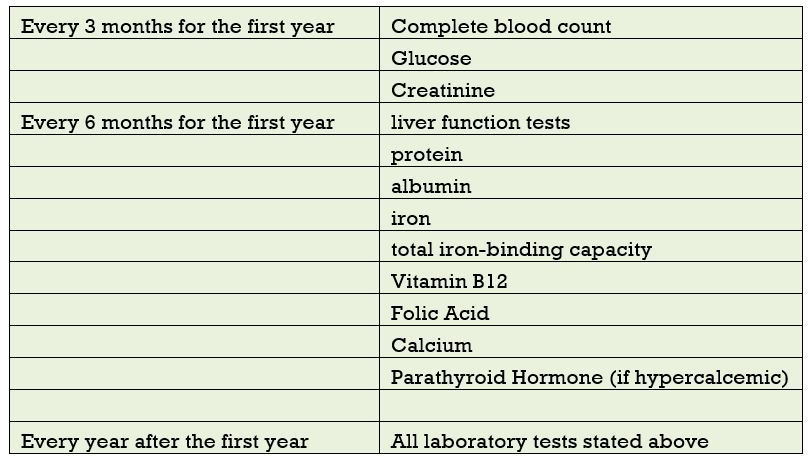

The work of Kashyap, et al (2010) states that obesity is a risk factor in the development and progression of type 2 diabetes and a primary component of this management is that of weight loss.“ After surgery, glycemic control is restored by a combination of enforced caloric restriction, enhanced insulin sensitivity, and increased insulin secretion.” (Kashyap, et al, 2010) The most commonly performed gastric bypass is the ‘Roux-en-Y’ gastric bypass as it is held to be the gold standard bariatric surgical procedure. The procedure is a common procedure although there are various long-term risks associated with this procedure. (Bal, et al, 2010) Due to the complex nature of this surgery there may be resulting “preventable perioperative complications” since the “normal anatomy and physiology of the upper gut” is altered during this procedure and this is stated to have adverse effects and potential complications which are of a predictable nature. (Bal, et al, 2010) The success of gastric bypass surgery is dependent upon such as lifestyle changes in diet and exercise.” (Indian Women’s Health, 2011) Furthermore, it is stated to be critically important for success that the patient makes an effective adaptation to a new manner of eating. (Indian Women’s Health, 2011) There are complications reported as linked to this type of surgery, which includes such as “bleeding…leaks from staple line, breakdown, infections, complications due to anesthesia and medication….” (Indian Women’s Health, 2011; Hamdam, Somers and Chang, 1998 in Drake, et al, 2009 and Dixon, et al, 2011) Bariatric surgery is reported to involve unique skin care needs for obese patients since they are “at higher risk of skin pressure ulcers and have skin folds that may present sites of breakdown, chronic dermatitis and fungal infection.” (Drake, et al, 2009) Bariatric surgery creates a lifelong change in patients’ anatomy, physiology, and overall health status. Postoperatively, patients commit to lifestyle changes that include physician follow-up and study.” (Drake, et al, 2009) The hospital-based perioperative phase of patient care is reported as the “shortest of all” stages, however, this makes provision for the change for early educational interventions that are effective in nature and that emphasize the importance of compliance to the follow-up orders of physicians and follow-up care. (Drake, et al, 2009, paraphrased) The primary difference between the types of bypass surgery two is stated to be the “method of gaining access to the abdomen.” (Drake, et al, 2009). The risks of bariatric surgery include factors relating to “preexisting comorbidities, experience of the surgeon and hospital volume of procedures act as independent predictors of complications.” (Virjl and Murr, 2006) Virjl and Murr (2006) report that the International Bariatric Surgery Registry, founded in 1986, reveals that the primary cause of death follow bariatric surgery is pulmonary embolism. (paraphrased) Risk factors for pulmonary embolism include “a BMI of 60 k per m2 or higher, chronic lower extremity edema, obstructive sleep apnea and previous pulmonary embolism.” (Virjl and Murr, 2006) Signs of anastomotic leak are “sustained tachycardia, severe abdominal pain, fever, rigors, and hypotension.” (Virjl and Murr, 2006) Work-up is stated to be inclusive of “an upper gastrointestinal series or computed tomography scan with contrasts and a prompt surgical consultation.” (Virjl and Murr, 2006) Determination of an anastomotic leak in patients often requires exploratory surgery in combination with “equivocal symptoms or diagnostic imaging studies.” (Virjl and Murr, 2006) Short-term complications of bariatric surgery are stated to be inclusive of “wound infection, stomal stenosis, marginal ulceration, and constipation.” (Virjl and Murr, 2006) Signs of wound infection include “fever, pain, erythema and purulence around the surgical site.” (Virjl and Murr, 2006) Wound infection may occur up to three weeks following surgery in obese patients. Treatment involves aggressive management? with “drainage and broad-spectrum antibiotics to optimize wound healing. Early wound infections also are associated with a higher risk of subsequent incisional hernias.” (Virjl and Murr, 2006) Virjl and Murr (2006) report that vomiting and intolerance to liquid meals are not normal following bariatric surgery and may indicate an organic cause other than overeating. (Virjl and Murr, 2006, paraphrased) Stomal stenosis occurs in 9 to 20 percent of patients following bariatric surgery and persistent vomiting occurs. Diagnosis of stomal stenosis is with an “upper gastrointestinal series and often is correctable by endoscopic dilation.” (Virjl and Murr, 2006) Additionally reported is “marginal ulceration along the surgical anastomotic site occurs in 1 to 16 percent of patients.” (Virjl and Murr, 2006) Early signs of a bleeding ulcer include “hamatemesis, melena, and orthostatic hypotension.” (Virjl and Murr, 2006) It is difficult to access the excluded stomach” in bariatric surgery patients therefore treatment requires “an endoscopic examination of the gastric pouch”. (Virjl and Murr, 2006) The nurse practitioner should teach the patient to avoid of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in order to bring about a reduction in “the incidence of recurrent marginal ulcer formation” in bariatric surgery patients.” (Virjl and Murr, 2006) Another short-term complication of bariatric surgery is that of constipation, often the result of “pain medicine or dehydration from poor fluid intake and malabsorption”. (Virjl and Murr, 2006) Patients who have bariatric surgery “often have significantly altered physiologic and anatomical pulmonary characteristics, when compared to non-obese patients” including “decreased lung expansion…” which often results in “hypoventilation and harder work for breathing.” (Drake, et al, 2006) Drake et al (2006) additionally state that the “reduced functional residual capacity (FRC) predisposes obese patients to the development of hypoxia, closure of small airways (atelectasis), and V/Q mismatch during normal breathing. Coexisting bronchitis, asthma, and other respiratory problems contribute to decreased lung compliance. Respiratory difficulties are often worsened in the supine and Trendelenburg position (which patients are in perioperatively), as both of these positions cause further decreases in FRC. Obese patients often have prolonged and difficult respiratory management requiring mechanical ventilation, which may be more difficult and often requires very high peak pressures, which can lead to barotraumas (pneumothorax).” (Drake, et al, 2006) In addition patients who have had bariatric surgery often have a history of sleep apnea and they are reliant on “continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)machines at home to adequately ventilate, especially at night while sleeping.” (Drake, et al, 2006) The nurse should be alert for “potential undiagnosed sleep apnea in all patients undergoing bariatric surgery.” (Drake, et al, 2006) Common monitoring parameters for bariatric surgery patients are the ‘follow-up periods’ with associated laboratory tests that are generally required.

Figure 1

Follow-Up Periods

(Virjl and Murr, 2006)

Successful gastric bypass surgery results in a reduction of body weight and an improvement in conditions including such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, improvement in diabetes, asthma and respiratory insufficiency as well as improvement in gastro-esophageal reflux disease, degenerative disk and joint disease as well as improvements in other conditions. (Indian Women’s Health, 2011, paraphrased) Another complication from the weight loss following bariatric surgery is that of the development of gallstones. (Anaise, nd)In addition, a danger following gastric bypass surgery is the development of an ulcer where the small intestine is attached to the upper part of the stomach. (Mayo Clinic, 2011)

Nutrients and Vitamins

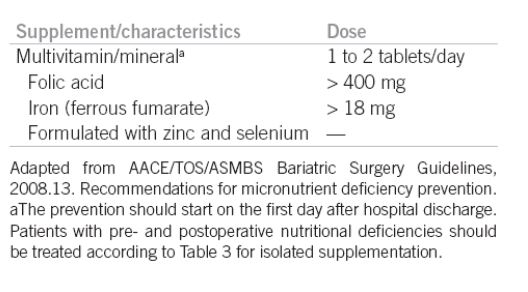

A common occurrence following gastric surgery is deficiency of Vitamin B12 as Vitamin B12 fails to separate from protein foodstuffs and fails in absorption of crystalline form of Vitamin B12. The use of 350 ug/day is reported to “generally correct a low level” of vitamin B12. (Rhode, Tamin, and Gilfix, 1995; Kushner, 2000; and Elliott, 2003 in Drake et al, 2009) The prevalence of B12 deficiency is “12-33%.” Clinical symptoms are stated to be “less common.” Only a very small percentage of patients will require “parenteral administration of B12 (2000 ug/month).” Reported as well is that thiamine deficiency “occurs through the combination of a reduction in acid production by the gastric pouch, restriction of food intake and frequent episodes of vomiting.” (Watson and Verma, 2004; Coskun, Bozbora, Ogunc, and Peker, 2004; Salas-Salvado, Garcia-Lorda, and Cuatrecasas, et al., 2000; Houdent, Verger, and Courtois, 2003; Christodoulakis,, Plaitakis, and Melissas, 1997; Koike, Misu, and Hattori, 2001; Seehra, MacDermott, Lascelles, and Taylor, 1996 in: Alvarez-Leite, 2004 in Drake et al, 2009) Thiamine deficiency “…is known to lead to certain neurological sequelae including Wernicke- Korsakoff encephalopathy. Signs attributable to this condition include ataxia, ophthalmoplegia, nystagmus, and mental confusion. Recognized predisposing conditions include alcoholism gastric carcinoma, pyloric obstruction, hyperemesis gravidarum, and prolonged intravenous feeding. We have recently encountered two cases of Wernicke’s encephalopathy after vertical banded gastroplasty for morbid obesity. Other neurological sequelae are recognized after vertical banded gastroplasty, including Guillain-Barre syndrome, psychosis, and pseudoathetosis, but the causes are multifactorial.” (Seehra, et al, 1996) The work of Fleischer, et al (2008) relates a study that reports findings that following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass “…there was evidence of calcium and vitamin D malabsorption. Bone turnover increased, and hipbone density rapidly declined. The decline in hip BMD was strongly associated with weight loss itself. Vigilance for nutritional deficiencies and bone loss in patients both before and after bariatric surgery is crucial.” Xanthakos (2009) reports that the causes of nutritional deficiencies in overweight and obesity are “multi-factorial and include decreased consumption of fruits and vegetables, increased intake of high calories, but nutritionally poor quality foods, as well as increased adiposity which may influence the storage and availability of some nutrients.” Xanthakos importantly notes that it is critical that practitioners “be aware of pre-existing nutritional deficiencies in overweight and obese patients and appropriately recognize and treat both common and rare nutritional deficiencies that may arise or worsen following bariatric surgery.” (2009) Follow-up of bariatric patients is stated in the work of Richardson, et al (2009) requires a lifetime of follow-up care “as care is complicated and lifetime follow-up is the key to long-term success.” The work of Bordalo, Teixeira, Bressan and Mourao (2011) report that following bariatric surgery that the “concern with micronutrient bioavailability influences on the supplementation efficacy. Accordingly, it is important to consider the quantitative and qualitative composition of marketed supplements.” Consideration of a supplements should be based on the following considerations:

- pH (acid or alkaline): required gastrointestinal pH to solubilize the nutrient;

- qualitative composition of the supplement: aqueous solution, capsule, powder;

- dependence of gastrointestinal enzymes assisting in some micronutrient absorption;

- bowel integrity and absorption surface;

- administration route: oral, intramuscular or intravenous, according to degree of nutritional deficiency;

- quantity and micronutrient type present in the composition. (Bordalo, Teixeira, Bressan and Mourao, 2011)

Figure 1 shows guidelines for the choice of preventive nutritional supplementation following bariatric surgery.

Figure 2

Guidelines for Choosing Preventive Nutritional Supplementation following bariatric surgery

Source: Bordalo, Teixeira, Bressan and Mourao (2011)

In a study reported by Hell, Miller, Moorehead, and Samuels (2006) it is reported that a comparison trial was conducted on the effects and outcomes of three bariatric procedures that were different and performed in two different center locations. It is stated that the “Standard Roux-en-Y gastric bypass was performed by Dr. Norman Samuels in Fort Lauderdale (Florida); vertical banded gastroplasty and laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding were done in Hallein (Salzburg) by Dr. Emanuel Hell and Dr. Karl Miller.” (Hell, Miller, Moorehead, and Samuels, 2006) The study matched 30 patients from each group and then followed them to post-operative assessment of improvement in health status and specifically in terms of patient’s “quality of life”. (Hell, Miller, Moorehead, and Samuels, 2006) The instrument used for measurement is the Bariatric Analysis and Reporting Outcome System (BAROS) “as described by Oria and Moorehead has been used for evaluation.” (Hell, Miller, Moorehead, and Samuels, 2006 ) The study reports that during the 3 year observation time of “at least 3 years (3 to 8 years) in each individual case. A significant increase in quality of life and health status in 75% of the surgically-treated patients was observed when compared with a non-operated control group of morbidly obese patients.” (Hell, Miller, Moorehead, and Samuels, 2006 ) The study concludes by stating that the utilization of BAROS made it possible for the results of different techniques in different procedures and using patients that came from various cultures and speaking different languages. The study reports favoring the standard gastric bypass for the treatment of morbid obesity. This operation is superior to purely gastric restrictive procedures in weight loss and improvement of quality of life.” (Hell, Miller, Moorehead, and Samuels, 2006)

Summary

This work has reviewed the literature on post-operative care of patients undergoing bariatric gastric bypass surgery and has noted that there are myriad potential complications that may arise from this procedure. Medical practitioners should necessarily be capable of predicting and managing such complications when they do arise. Complications include such as respiratory, wound healing as well as other problems such as those cited in the work of Kashyap, et al (2010) resulting from significant loss of weight and diabetes remission which involves the restoration of glycemic control through caloric restrictions being enforced and involving increased secretion. Pre-existing comorbidities are stated to be independent predictors of complications which include such as stomal stenosis, incisional hernia, small bowel obstruction, marginal ulcer, wound infection and bleeding in addition to Anastomotic leak, deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolus and finally operative mortality. Common parameters for monitoring bariatric surgery patients have also been reviewed and as noted include requirements specifically stated for each follow-up period following bariatric surgery including every three month follow-up, every six-month follow-up and every year follow-up which involves a lifelong process of care. Included in the testing are such as complete blood count, glucose, creatinine, liver function tests, protein and albumin, iron, total iron-binding capacity, ferritin, Vitamin B12, folic acid, calcium, parathyroid hormone and hypercalcemic. With the increase of bariatric surgery, the nurse practitioner and other medical practitioners will be required to be knowledgeable and skilled in this area of health care provision.

References

Alvarez-Leite, JI (nd) Nutrient Deficiencies Secondary to Bariatric Surgery. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 7:569–575. # 2004 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Retrieved from: http://nutritioncenter.wustl.edu/NutritionSupport/training%20files/NutrDef2ary_bariatric_surgery.pdf

Anaise, David (nd) Bariatric Surgery: A Review. Retrieved from: http://www.danaise.com/bariatric.htm

Baol, B. et al (2007) Managing Medical, and Surgical Disorders After Divided Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery. Obes Surg. 2007 May;17(5):617-21.

Bariatric Surgery (2011) Mayo Clinic. Possible Complications. Retrieved from: http://www.mayoclinic.org/bariatric-surgery/complications.html

Bozbora A, Coskun H, Ozarmagan S, et al. A rare complication of adjustable gastric banding: Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Obes Surg 2000; 10:274–275.

Chang CG, Adams-Huet B, Provost DA. Acute post-gastric reduction surgery (APGARS) neuropathy. Obes Surg 2004; 14:182–189.

Chaves LC, Faintuch J, Kahwage S, Alencar Fde A. A cluster of polyneuropathy and Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome in a bariatric unit. Obes Surg 2002; 12:328–334.

Christodoulakis M, Maris T, Plaitakis A, Melissas J. Wernicke’s encephalopathy after vertical banded gastroplasty for morbid obesity. Eur J Surg 1997; 163:473–474.

Cirignotta F, Manconi M, Mondini S, et al. Wernicke-korsakoff encephalopathy and polyneuropathy after gastroplasty for morbid obesity: report of a case. Arch Neurol 2000; 57:1356–1359.

Coskun H, Bozbora A, Ogunc G, Peker Y. Adjustable gastric banding in a multicenter study in Turkey. Obes Surg 2003; 13:294–296.

Dixon, JB, et al (2011) Surgical Approaches to the Treatment of Obesity. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011 Jul5;8(8) 429-37.

Drake, D.J. (2009) Post Operative Nursing Care of Patients After Bariatric Surgery. Perspectives. Vo. 6 Nol 4. Retrieved from: http://www.perspectivesinnursing.org/pdfs/Perspectives24.pdf

Fleischer, J. et al (2008)The Decline in Hip Bone Density after Gastric Bypass Surgery Is Associated with Extent of Weight Loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 October; 93(10): 3735–3740. Published online 2008 July 22. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0481

Hamdam, K., Somers, S., and Chang, M. (2011) Management of Late Postoperative Complications of Bariatric Surgery. Br J Surg 2011 Oct;98(10):1345-55.

Hell, E., Miller, KA, Moorehead, MK and Samuels, N. (2006) Evaluation of Health Status and Quality of Life after Bariatric Surgery: Comparison of Standard Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass, Vertical Banded Gastroplasty and Laparoscopic Adjustable Silicone Gastric Banding. Obesity Surgery, Volume 10, Number 3, 214-210.

Houdent C, Verger N, Courtois H, et al. Wernicke’s encephalopathy after vertical banded gastroplasty for morbid obesity. Rev Med Interne 2003; 24:476–477 in: Drake, D.J. (2009) Post Operative Nursing Care of Patients After Bariatric Surgery. Perspectives. Vo. 6 Nol 4. Retrieved from: http://www.perspectivesinnursing.org/pdfs/Perspectives24.pdf

Kashyap, et al (2010) Bariatric surgery for type 2 diabetes: Weighing the impact for obese patients. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010 July; 77(7): 468–476.

Koike H, Misu K, Hattori N, et al. Postgastrectomy polyneuropathy with thiamine deficiency. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 71:357–362 in: Drake, D.J. (2009) Post Operative Nursing Care of Patients After Bariatric Surgery. Perspectives. Vo. 6 Nol 4. Retrieved from: http://www.perspectivesinnursing.org/pdfs/Perspectives24.pdf

Kushner R. Managing the obese patient after bariatric surgery: a case report of severe malnutrition and review of the literature. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2000; 24:126–132 in: Drake, D.J. (2009) Post Operative Nursing Care of Patients After Bariatric Surgery. Perspectives. Vo. 6 Nol 4. Retrieved from: http://www.perspectivesinnursing.org/pdfs/Perspectives24.pdf

Rhode BM, Tamin H, Gilfix BM, et al. Treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency after gastric surgery for severe obesity. Obes Surg 1995; 5:154–158.

Salas-Salvado J, Garcia-Lorda P, Cuatrecasas G, et al. Wernicke’s syndrome after bariatric surgery. Clin Nutr 2000; 19:371–373 in: Drake, D.J. (2009) Post Operative Nursing Care of Patients After Bariatric Surgery. Perspectives. Vo. 6 Nol 4. Retrieved from: http://www.perspectivesinnursing.org/pdfs/Perspectives24.pdf

Seehra H, MacDermott N, Lascelles RG, Taylor TV. Wernicke’s encephalopathy after vertical banded gastroplasty for morbid obesity. BMJ 1996; 312:434 in: Drake, D.J. (2009) Post Operative Nursing Care of Patients After Bariatric Surgery. Perspectives. Vo. 6 Nol 4. Retrieved from: http://www.perspectivesinnursing.org/pdfs/Perspectives24.pdf

Seehra, H. (1996) Wernicke’s encephalopathy after vertical banded gastroplasty for morbid obesity. BMJ. 1996 February 17; 312(7028): 434 in: Drake, D.J. (2009) Post Operative Nursing Care of Patients After Bariatric Surgery. Perspectives. Vo. 6 Nol 4. Retrieved from: http://www.perspectivesinnursing.org/pdfs/Perspectives24.pdf

Sola E, Morillas C, Garzon S, et al. Rapid onset of Wernicke’s encephalopathy following gastric restrictive surgery. Obes Surg 2003; 13:661–662 in: Drake, D.J. (2009) Post Operative Nursing Care of Patients After Bariatric Surgery. Perspectives. Vo. 6 Nol 4. Retrieved from: http://www.perspectivesinnursing.org/pdfs/Perspectives24.pdf

Wittgrove, A. (2011) Treatments the Risks and Benefits. Wittgrove Bariatric Center. Retrieved from: http://www.lapbypass.com/risks-and-benefits/

Weight Loss Surgery (2011) India Women’s Health. Retrieved from: http://www.indianwomenshealth.com/Weight-Loss-Surgery-274.aspx

Xanthakos, S.A. (2009) Nutritional Deficiencies in Obesity and After Bariatric Surgery. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009 October; 56(5): 1105–1121.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee