Writing Apprehensions of ELL Students, Article Writing Example

Getting ELL Students Out of Their Shells: Enhancing Student Engagement through Writing

Abstract

When teaching students that speak a foreign language how to speak English or any other second language, engaging the students in the lesson is integral to the students’ achievement of maximum retention of the lesson. However, engaging English language learners (ELL) students tends to be difficult due to the multitude of multicultural differences that may exist between the teacher and the many different nationalities that comprise ELL students. Further compounding the problem of engagement are language anxiety (LA) or foreign language anxiety (FLA), which are interchangeable phrases used to conceptualize the same circumstance ELL students experiences when they are asked to complete any assignment involving explicit use of the second language (L2) and become overwhelmingly nervous. Writing and group activities have both been identified as effective tools for engaging students of all paradigms in the material being taught and reducing the occurrences of LA or FLA amongst ELL students. This research explores the occurrence of LA or FLA amongst several classes of ELL students to determine how effective writing and group are at alleviating the occurrence of student anxiety in conjunction with L2 assignments and whether these tools help get ELL students out of their shells to help facilitate learning and retention of the L2 for students learning another language. The determinations extrapolated from the surveys administered to ELL students indicated that the participants were less likely to experience LA or FLA when L2 writing involved group exercises as opposed to individual exercises.

Keywords: Ell, La, Fla, Anxiety, Language Anxiety

Introduction to the Problem

The physical condition known as anxiety has been categorically defined as three specific forms, identified as trait anxiety, which denotes this condition as a personality trait; state anxiety that occurs when an individual experiences apprehension at a precise moment in time; and situational anxiety that occurs within the context of a well-defined situation (Awan, Azher, Anwar, & Naz, 2010). The feeling of nervousness associated with language learning termed as language anxiety (LA) is a form of situational anxiety (Awan, Azher, Anwar, & Naz, 2010). The term ‘foreign language anxiety’(FLA) is typically used to describe a generally vague impression of apprehension or fear that can arise when English language learner (ELL) students are engaged in different kinds of activities performed both in and out of the classroom designed to facilitate the acquisition of the second language (L2) (Chen, Kyle, & McIntyre, 2008; King, 2013). Foreign language anxiety is determined to stem from a multifaceted collective of behaviors, self-perceptions, feelings, and beliefs associated with classroom language learning derived from the distinctiveness of the language learning process (Chen & Chang, 2009). In the context of this definitive explanation, three overall constituents of language anxiety have been proposed, which are test anxiety, fear of negative evaluation, and communication apprehension (Young, 1991). Although language anxiety is sometimes viewed as a helpful facilitator of successful completion of the complex tasks required of L2 learning, it can also evolve into a debilitating anxiety, or writing apprehension, which cannot be easily dismissed (Awan, Azher, Anwar, & Naz, 2010). The potentially harmful effects of anxiety can occur frequently in the context of L2 teaching and learning (Trang, 2012).

It has been theorized that scaffolding for ELL learners through group activities can reduce the severity of language anxiety as well as writing apprehension and help improve the outcomes for the completion of the L2 activity (Foss & Reitzel, 1988). Research concerning the efficacy of pairing ELL students in groups using associative learning techniques indicates that these situations encourage oral participation when L2 students collaborated through group learning, their motivation increased, they took more initiative, and experienced lower levels of anxiety regarding their learning (Tong, 2010; Trang, 2012). This study will explore whether writing assignments that include scaffolding are more effective at enhancing student engagement through writing by encouraging and engaging ELL students in the L2 activity as opposed to writing assignments that require individual completion.

Research Aim & Objectives

The aim of this research is to examine the impact of writing apprehension on ELL learners and their ability to retain the lesson with the intention of providing an overview of the most prominent problems as well as solutions. Second language learning should be instituted within the context of the micro-social structures of the educational setting (Campbell, Combs, Kovar, Napper-Owen, & Worrell, 2009). Integrating a socio-cultural approach addresses the need to expound on situations involving instruction in linguistic knowledge that can be improved by social and cultural institutional structures as well as the understanding of how teaching relates to the pedagogical practices and the social background of the learners (Ajayi, 2008b). In examining the paradigms involving the occurrence of language anxiety, the specific objectives of this research are to:

Specify the attributes and characteristics of language anxiety;

Identify the frequency or prevalence in which ELL students experience language anxiety; and

Specify the contexts of associative learning through group scaffolding and how this supports improved learning experiences for ELL students

Learning strategies are very susceptible to the learning context as well as the students’ cognitive capabilities. Different tasks require different learning strategies that will help the learner achieve predetermined learning goals (Griffiths & Parr, 2001).

Research Question & Hypothesis

In achieving these aims and objectives, this research will be guided by the flowing research questions:

Do ELL students experience language anxiety more frequently when they engage in L2 exercises that necessitate individual work as opposed to activities that include associative learning/scaffolding through group work?

Do L2 activities that integrate associative learning through group scaffolding improve ELL students’ writing apprehension and enhance student engagement?

In seeking the answer to these research questions, it is hypothesized that:

ELL students frequently experience language anxiety but this is greatly reduced through associative learning exercises that provide opportunities for scaffolding to assist learning.

L2 activities that integrate associative learning strategies enhance student engagement in the writing activities and facilitate learning as well as retention of the lesson better than activities requiring individual efforts.

The overall influence of teachers on student learning must be analyzed against the findings that have established certain practices as counter-intuitive in the acquisition of a second language (Katyal, 2005). These same counter-intuitive practices have been examined to assess the relevant factors specify that teacher leadership has a pronounced effect on the degree of each student’s scholastic engagement (Katyal, 2005). However, teacher leadership, student engagement and home/school interaction are three areas of import that require additional clarification. The student’s desire to become engaged in scholastic activities must be voluntary in order to facilitate an environment conducive to learning and ensure the student will adhere to proper classroom etiquette and protocol.

Review of Literature

…written language functions as both statements and linguistic artifact, demanding of the reader an “awareness of language as language.”

ELL Development

For ELL students, the foundation they base all future knowledge regarding language acquisition is derived from the linguistic paradigms of their mother tongue (Hussein, 2013). The increasing number of ethnically diverse students exponentially increases the likelihood that there will be numerous individuals that do not speak English as their first language and are therefore vulnerable to experiencing FLA when asked to engage in L2 activities (Gholson & Stumpf, 2005). All of the attributes of the student’s daily environment can have a drastic impact on the student’s ability to become literate in the target language (Feeney, Moravcik, Nolte, & Chritensen, 2010). Teachers that are properly educated in the implementation of pedagogical formats tend to be conscientious of the student’s needs, so they are more successful in helping their diverse students have a positive learning experience while becoming fluent in their new language (Casteel & Ballantyne, 2010).

How students interpret and comprehend spoken words determines whether they are able to develop the phonetic skills to become literate and understand written words (Giorgis & Glazer, 2008). When students develop oral competencies, they learn how to mimic the sounds as they gain an understanding of the implications of the words being spoken to them, which increases their ability to articulate thoughts, ask questions, and be better learners. Oral competency enables students to demonstrate superior literacy aptitudes in phonemic awareness, vocabulary development, syntactic comprehension and production, as well as narrative awareness and production. Facilitation of literacy development in oral language competencies includes growth in areas that will help the student acquire the skills to become literate.

Impact of FLA & LA on Learning

Experiencing FLA or LA has been determined to have ensuing effects on L2 learning and lesson retention, which can present a significant challenge to educators as well as the student since it has substantial potential to hinder the optimal learning achievement (Awan, Azher, Anwar, & Naz, 2010). The L2 teaching context may also be considered as a source of anxiety if it does not support multicultural learning and this can be challenging for educators create such an open environment within the classroom (Eberly, Joshi, Konzal, & Galen, 2010). Existing research on FLA and language learning anxiety has offered insights into the nature of LA experienced by L2 learners in their learning processes (Chen, Kyle, & McIntyre, 2008).

Strategies that include relaxation techniques have been noted to help teachers create a non-threatening and relaxing atmosphere in the ELL classroom, but the research does not indicate whether the strategy actually facilitates a reduction of anxiety on the part of each individual student in class (Ajayi, 2008a). The primary concern of such anxiety-reduction techniques has previously concentrated on the teachers’ ability to help students cope with their anxiety, particularly in the language classrooms (Ajayi, 2008a). In L2 learning, one blanket solution will not adequately support the L2 development of all ELL students since the acquisition of language is a complex phenomenon, which makes FLA equally complex (Helfrich & Bosh, 2011). Additionally, the actual manifestations of LA can vary from one student to another, reflecting each student’s individual differences (Nassaji & Fotos, 2011). In this capacity, it is appropriate to emphasize that each student has his/her own manner of dealing with their anxiety, which corresponds to their individual characteristics.

While assumptions typically favor the notion that teachers have the responsibility to help students overcome their LA by providing a relaxing multicultural learning environment, the complex and multidimensional facets of anxiety place undue pressures on the skills of the teacher (Casteel & Ballantyne, 2010). However, providing writing assignments to ELL students has been noted as an effective tool for facilitating engagement as well as affective self-management in students (Payán & Nettles, n.d.). This suggestion does not imply that the teachers then become exempt from their responsibility to engage students despite their anxiety, but that both teachers and students can share the responsibility so that both sides can benefit from each other in their attempts to manage language anxiety in a collaborative manner (Casteel & Ballantyne, 2010). The potential benefits of writing, which are often neglected in ELL learning contexts because of the emphasis placed on other language skills, such as listening, speaking, and reading, is worth examining based on its relevance to the development of those other skills in addition to its utility as an affective FLA managing tool (Goldenberg, 2008).

Benefits of Writing

There are several established benefits associated with the act of writing that have been cited in literature although it has also been noted that such benefits vary from one person to another, depending upon the personal level of affinity toward writing. Prewriting exercises such as brainstorming is one example of how the potential of writing can be used regardless of the different levels of ELL mastery the student has (Katyal, 2005). Additional practical benefits gained from writing can be quite different based on the individual differences in the manner in which each student approaches the various writing activities, but this does not detract from the comprehensive value that writing has for ELL learners (Samson & Collins, 2012). Basically, the true value of writing is derived from the innate qualities that permit multiple variations of the same technique to be applied in response to each student’s individual needs and purposes (Wei, Brok, & Zhou, 2009).

Writing is an irreplaceable utility with notable benefits that other language or non-language alternatives cannot offer. Several specific benefits of writing include the ability to formulate tangible constructs, establish self-revealing attributes, and facilitation of deeper thought. Writing helps formulate tangible constructs because it provides opportunities for the writer to examine his/her ideas with objectivity and have the ability to scrutinize the language they produce in a way that native speakers cannot (Trang, 2012). It is through the tangible nature of writing that ELL students are able to perceive the connection between the writer and what is being written, which naturally involves negotiation of meaning through interaction between the two. Furthermore, writing enables language to be regarded as an object, or language data to be examined and discussed through the use of meta-language (Goldenberg, 2008).

Writing can be self-revealing because, unlike spoken language, writing does not require an audience other than the writer unless it is intended for either informal or formal publication and will be read by others. The personal possibility of writing provides a sense of security and comfort that enables the writers to freely explore their ideas or thoughts during as well as after the writing process, which can also contribute to the facilitation of the self-searching or self-analysis processes through deconstruction and reconstruction (Helfrich & Bosh, 2011). In such processes, beliefs or assumptions can be challenged in a retrospective manner before they are reconstructed based on self-discovery and analysis. In this respect, writing allows students to view the reality from a different perspective as it draws them into a search for a connection between cognitive and intuitive understanding of the world (Ajayi, 2008b).

The tangible nature of writing can facilitate deeper thought by providing opportunities for the critical examination of the student’s ideas as well as their revision. This demonstrates that the relationship between thought and writing is not unidirectional one, but instead can be influenced either way, constructing an inter-directional or interactive relationship that facilitates the development of both thought and writing (Ajayi, ESL, 2008a). Although some theorists claim that writing has enabled abstract thought and explicit manner, the same kind of abstract thinking can also be accomplished in some forms of speech, such as lectures, since ideas in these contexts are often highly elaborated or explicit in comparison to the succinctness of some forms of writing, such as personal notes or memos (Ajayi, ESL, 2008a). This demonstrates that the relationship between thought and writing is actually interdependent, whereas improvement brings benefits to the growth and refinement of both entities. It is also suggested that the reciprocity between writing and thought is such that writing empowers specific types of, but the potential of thought is what makes writing possible even though writing can facilitate thought.

Theoretical Frameworks for Understanding Language Development

Linguistic and ethnic diversity impacts the ELL student’s ability to learn, particularly if the teacher has not received pedagogical training educating them on how to integrate multicultural instructional methods into their educational environment (Otto, 2010). Furthermore, a multitude of aspects within the student’s environment also affect their ability to develop literacy skills that the educator must consider, such as the individual traits of the student, the learning environment, and the quality and quantity of the linguistic input the student receives within the home (Ball, 2010; Crim, et al., 2008). The nativist perspective on language development emphasizes innate linguistic capabilities as the primary contributory factor to language development in students (Morrison, 2009). This perspective of linguistic acquisition encourages educators to employ a curriculum that will allow numerous opportunities for students to explore language and explore various aspects of their growing knowledge and keep their language acquisition device (LAD) active (Morrison, 2009).

The cognitive development perspective speculates that linguistic acquisition comes with maturation and cognitive development, which is the foundation for teaching language (Ball, 2010). This perspective encourages educators to pay close attention to the cognitive developmental stages of young students to encourage stimulatory activities as precursors to the onset of linguistic development (Hill, 2007). The behaviorist perspective highlights the role of “nature” and the stimuli, responses, and reinforcements that occur in the student’s environment based on ‘operant conditioning’ along with the notion that students are “blank slates” before they are taught through various situations and learn language through imitative speech (Decker, Decker, Freeman, & Knopf, 2009). This perspective encourages teachers to focus on the types of stimuli and reinforcements regarding language that students encounter and would encourage them to communicate verbally.

Research Method

For this research paper, the qualitative empirical research method was followed with an aim to examine the relationship between language anxiety and group learning. The research design elucidates the strategy used to integrate the various facets of the research project in a coherent and cohesive manner (Flick, 2011). The study involves non-numerical data, which imparts empirical attributes to the research since the information is retrieved from textual analysis of the questionnaires. As such, this enquiry will be predominantly empirical although the established framework is derived from extensive literature in this area (Creswell, 2009). Since the research will be primarily empirical, much data will be collected through observations, self-administered questionnaires with explicit instructions and discussions with willing participants (Creswell, 2009).

Research Design

A case study approach has been employed to investigate the language development in the writing and reading processes of the ELL learner. The reason for adopting the approach is that it is inductive, heuristic, and descriptive (Graziano & Raulin, 2009). Based on research that has been conducted, the case study is a careful and holistic view of the relative context of the study. With this view, the researcher chose to examine the writing, and reading experiences of the ELL learners that have attended courses taught by the researcher for easy accessibility to willing participants.

Participants

The participants are ELL learners who are studying English formally whose English proficiency ranges from beginner to upper/intermediate levels. It is very crucial to any teacher to know, and identify the learners’ present strategies, strengths, and weaknesses to determine his/her baseline achievement so that any subsequent progress can be adequately measured. This will assist the teacher in implementing the new strategies so that the performance of the learners is improved. The participating students encompass 480 ELL learners that have completed the surveys completely and accurately.

Data Collection Method

The study was conducted over a course of three years using students already enrolled in a total of 24 Freshman Composition 1, Freshman Composition 2, or Business Writing classes taught by the researcher. The learner was given writing and reading exercises both individually and assigned to a group for cooperative completion. The task was to produce writing described as creative, and the participants were also requested to read their individual writing and group writing in front of the class in order to assess their reading skills. The participants were instructed to be imaginative and produce writing that depicts their childhood experiences for both assignments.

The respondents were made to be at ease by informing them that this was not a test, and there was no need to panic or become tense when giving answers, and that any answer given was neither wrong nor right. The participants were also instructed to ask for any clarification if needed. During the whole exercise, the researcher remained in order to observe and collect data. The respondents were given all the necessary items. A duration of thirty minutes was given to the respondents for each assignment, with an additional three minutes to read the writing out loud, and the researcher ensured that time was adhered to. Once the writing task was over, the respondent was interviewed using the survey presented in Appendix A: Aggregate Survey Results, which asked specific Likert-scaled, yes/no, or multiple choice questions that were designed to determine whether the participant experienced LA, the perceived causes, and the degree in which respondents experienced LA during individual assignments versus when they were paired with peers in group assignments.

Ethical Issues

In order not violate the ethical considerations of the respondent, all participants were fully informed by verbal, and written forms, in a language that they best understand regarding all their respective rights. Each participant was well informed of what was required from him/her, how the information collected was to be used, and that all the information given was anonymous to protect privacy. The respondents were also asked sign a form of consent showing that he/she agreed and was providing information of their own free will.

Results

This section will detail the results of the survey questionnaire interspersed with observational notes collected by the researcher during the course of the study. The survey contained various multiple choice Likert-based questions with five or seven options, such as ‘not anxious at all, slightly anxious, moderately anxious, very anxious, and extremely anxious’ for the five option questions; and ‘strongly disagree, disagree, slightly disagree, neither disagree nor agree, slightly agree, agree, and strongly agree for the seven option questions, as well as the analysis of the results for each individual survey question will first be presented followed by demographic details of the participants. The results will be presented in the form of graphical illustrations to represent the research findings. Following the presentation of the results, a discussion of the determinations that can be drawn from these results will present a comparative examination of how these results represent norms in ELL education.

Survey Results

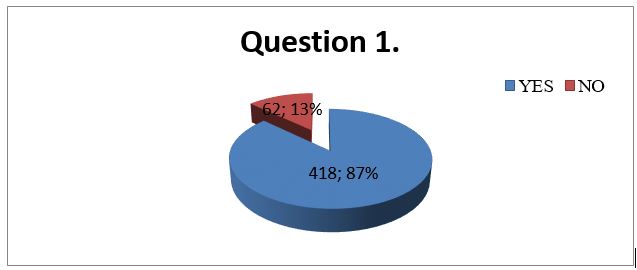

The survey questions are preluded by instructions that state: ‘This survey is intended to examine your experience with language anxiety. Language anxiety is used to describe feelings of apprehension experienced in association with completing a written L2 assignment. Please answer each question completely. Your participation is appreciated.’ The survey was presented to each student written in their native tongue to avoid complications due to linguistic misinterpretation. With the understanding of LA established, the first question asked: Have you ever experienced language anxiety? The results are shown in Figure 1: Results of Survey Question One below which illustrates that 87% or 418 students reported having experienced LA while 13% or 62 students stated they had not experienced it.

Figure 1: Results of Survey Question One

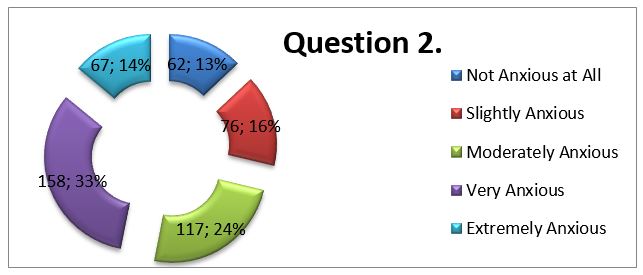

The next survey question asks: To what extent was your level of anxiety? The responses are designated based on a five-point Likert scaled selection, where the respondents could answer Not Anxious at All; Slightly Anxious; Moderately Anxious; Very Anxious; or Extremely Anxious. The respondent answers for this question are shown in Figure 2: Results of Survey Question Two, shown below.

Figure 2: Results of Survey Question Two

The majority of student respondents, 33% or 158, selected ‘very anxious’ while the next largest cohort, 24% or 117, selected ‘moderately anxious’. The response, ‘slightly anxious’ was the next largest cohort at 16% or 76 students, while 14% or 67 students selected ‘extremely anxious’ and only 13% or 62 students stated they were ‘not anxious at all.’

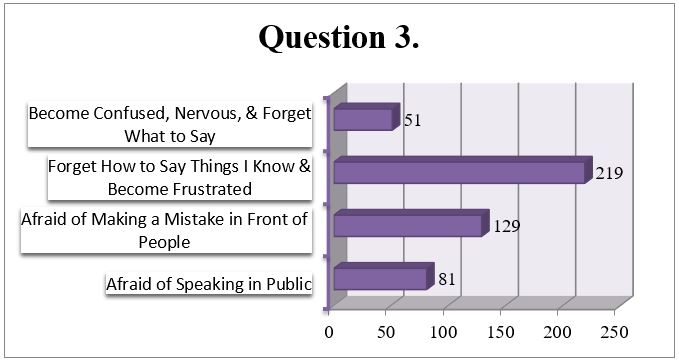

The third survey question asked: Could you tell me the reasons why you experienced language anxiety? The respondent results for this question are shown in Figure 3: Results of Survey Question Three below, which shows that the vast majority of students, 45% or 219, stated that the reason why they experience LA is because they ‘become frustrated’ because they forget how to express their thoughts.

Figure 3: Results of Survey Question Three

The next larges response group at 27% or 129 students stated that they are ‘afraid of making a mistake’ in front of their peers and 17% or 81 student said they were ‘afraid of speaking in public’ while 11% or 51 students said they ‘become confused, nervous, and forget what to say’ when asked to complete a L2 assignment.

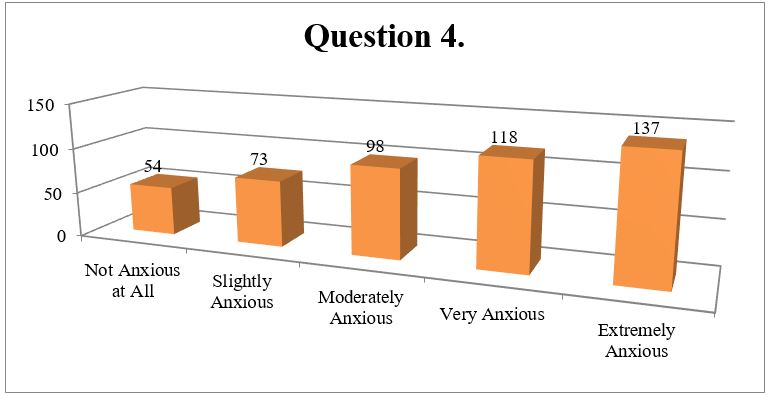

The fourth survey question asked about the participants’ level of anxiety in an independent L2 assignment, shown in Figure 4: Results of Survey Question Four using the same Likert scale previously mentioned, and 29% or 137 stated such assignments made them ‘extremely anxious.’

Figure 4: Results of Survey Question Four

The next largest cohorts were 25% or 118 students that stated they were ‘very anxious’, 20% or 98 students that were ‘moderately anxious, 15% or 73 students that were ‘slightly anxious’, and 11% or 54 students that said they were ‘not anxious at all’ when given independent L2 writing assignments.

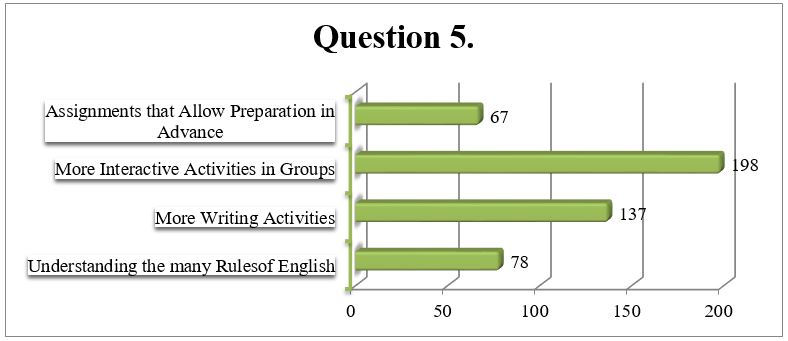

The fifth survey question asked what would encourage participation in a writing activity without anxiety, shown in Figure 5: Results of Survey Question Five below.

Figure 5: Results of Survey Question Five

The majority of students, 41% or 198, indicated that ‘more interactive group activities’ would facilitate greater participation while 29% or 137 students stated ‘more writing activities’ would engender their engagement, and 16% or 78 and 14% or 67 students stated ‘understanding the rules of English’ and being able to prepare in advance for the assignments, respectively, would spark greater engagement.

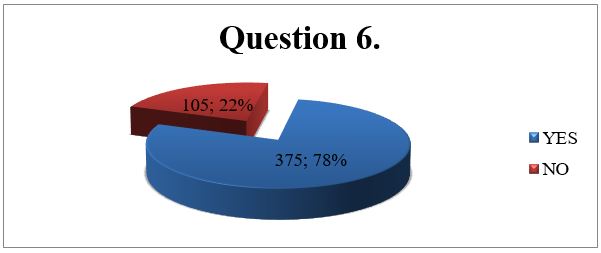

The sixth survey question, shown in Figure 6: Results of Survey Question Six below asks whether participants experienced LA during group writing exercises and the results show 78% or 375 students said they do while 22% or 105 students said they do not.

Figure 6: Results of Survey Question Six

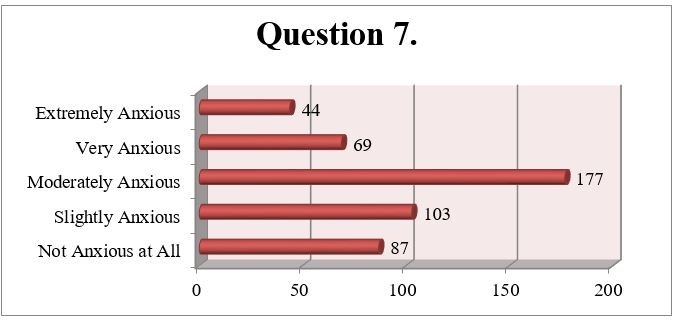

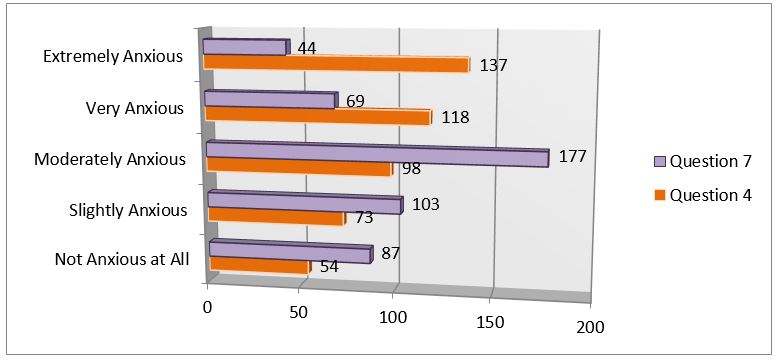

The next question, shown in Figure 7: Results of Survey Question Seven below asks about the level of the students’ anxiety when participating in a group writing activity.

Figure 7: Results of Survey Question Seven

The majority of participants, 37% or 177 students, indicated that they were ‘moderately anxious’ about completing a L2 assignment in a group while the next largest cohort, 22% or 103 students, stated that they were only ‘slightly anxious,’ and of the remaining participants, 18% or 87 stated they were ‘not anxious at all,’ while 14% or 69 stated that they were ‘very anxious,’ and 9% or 44 students said that they were ‘extremely anxious.’

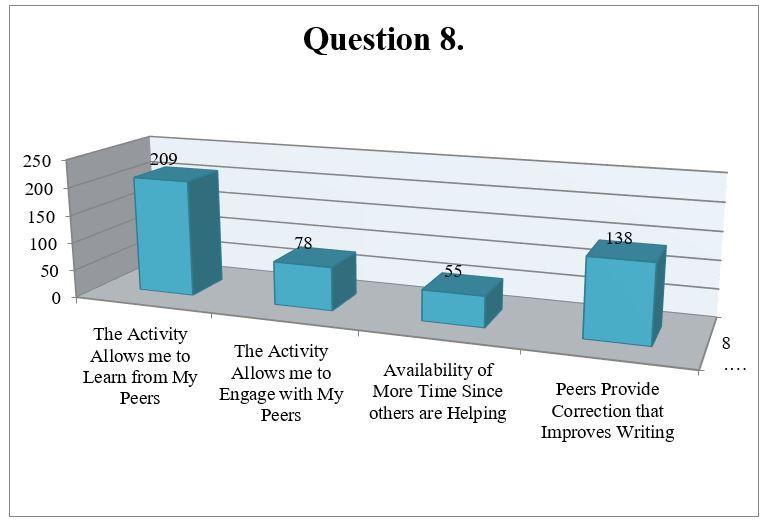

The results of the eighth survey question show in Figure 8: Results of Survey Question Eight below asked about the perceived factors students thought contributed to the group writing activity being less likely to cause anxiety than an independent writing exercise.

Figure 8: Results of Survey Question Eight

The majority of the respondents, 44% or 209 students, indicated that their reason was because the activity allowed the opportunity for them to learn from their peers, 29%or 138 students said that peers corrected errors in their writing, 16% or 78 participants indicated that group activity enabled them to engage with their peers, and 11% or 55 individuals indicated that the assistance of group members made the activity less time consuming.

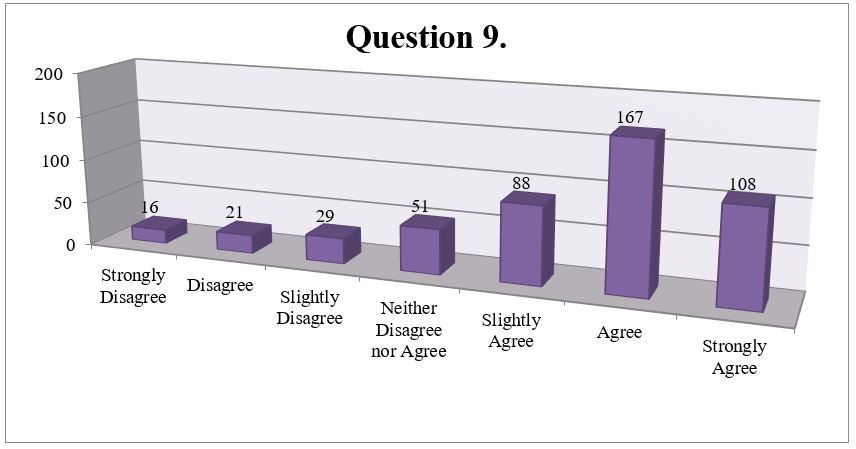

Question nine of the survey asked participants whether they experienced less anxiety when engaged in L2 group activities and the response selection was based on a seven point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree.’ The participant results for question nine are shown in Figure 9: Results of Survey Question Nine below.

Figure 9: Results of Survey Question Nine

The largest cohort of 35% or 167 students agreed with the statement while the next largest cohort of 23% or 108 said they strongly agreed and 18% or 88 participants indicated that they slightly agreed, placing a total of 76% of participants in agreement with this statement. Of the remaining participants, 11% or 51 students stated they neither agreed or disagreed with the statement, 6% or 29 students said they slightly disagreed, 4% or 21 students said they disagreed, and 3% or 16 participants said that they strongly disagreed with the statement.

The results from survey questions one through nine enabled the researcher to determine an answer to the first research question, which asked about the frequency of LA in regards to group work as opposed to individual L2 assignments. The fourth and seventh survey questions are compared in Figure 10: LA Experience in Group vs. Individual L2 Writing Exercises, which shows that a total of 45% or 255 students indicated they were extremely or very anxious and only 20% were ‘moderately anxious’ in response to question four whereas responses for question seven, only 25% or 113 students indicated that they were extremely or very anxious.

Figure 10: LA Experience in Group vs. Individual L2 Writing Exercises

This supports the first hypothesis that ELL students frequently experience language anxiety but this is greatly reduced through associative learning exercises that provide opportunities for scaffolding to assist learning.

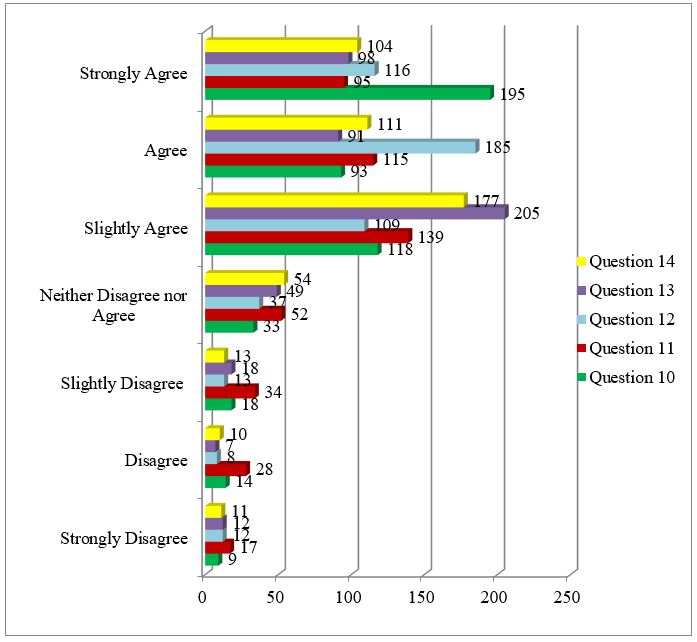

The results to questions ten through fourteen are shown in Figure 11: Results of Survey Questions 10-14 below, which also provides a comparative view of the series since they are all based on the same seven-option Likert-based scale.

Figure 11: Results of Survey Questions 10-14

Question ten asked whether students felt more confident when completing group assignments as opposed to independent assignments. Overall, 84% of the students indicated some form of agreement in response to this question while 7% did not agree or disagree and the remaining 9% indicated some form of disagreement with the statement. The next survey question, number 11, asked if students agreed that they felt more confident about their overall knowledge during group assignments, of which a total of 16% indicated some level of disagreement with this statement and 11% did not agree or disagree. The remaining 73% indicated some level of agreement to the statement.

The third survey question in Figure 11: Results of Survey Questions 10-14 is number 12, which asks if students agree that scaffolding & associative learning in group writing assignments enhance the educational experience, to which a total of 85% of the students indicated some degree of agreement. While 8% indicated they did not agree or disagree, the remaining 7% indicated some level of disagreement with the statement. However, question 13 asked students whether they agreed that they learned more during group exercises than during independent assignments, a total of 82% of the students agreed to some degree that they had while 10% did not agree or disagree and the remaining 8% disagreed to some degree. The final question in the series, number 14, asked students if they agreed that their experience of LA was significantly reduced in group activities as opposed during independent assignments, to which 82% of the students agreed to this statement to some degree while 11% did not agree or disagree and the remaining 7% indicated that they disagreed with the statement in varying degrees.

Overall, the answers to survey questions 10-14 enabled the researcher to determine an answer to the second research question, which asked whether L2 activities that integrate associative learning through group scaffolding improved ELL students’ writing apprehension and enhanced student engagement. The overwhelming majority of students that agreed to the series of statements in varying levels as opposed to the percentages that disagreed showed that more students experienced educational benefits than did not. This also supports the second hypothesis, which posited that L2 activities that integrate associative learning strategies enhance student engagement in the writing activities and facilitate learning as well as retention of the lesson better than activities requiring individual efforts.

Discussion

In addition to the four options that encourage ELL students to participate in L2 activities mentioned in question five, studies suggest that the degree of oral or written participation students’ give is increased if application and presentation activities are used; the right vocabulary is offered when students need it to continue; questions related to students’ prior experiences are asked; and an informal and friendly classroom atmosphere is present (Tong, 2010, p. 240). When sociolinguistic skills improved, conversation increased as did the grammatical analytical input, and accuracy, which decreased the negative feedback that verbal hypothesis testing elicits (Tong, 2010, p. 240). Individuals have psychological and social differences that contribute to the uniqueness of each student, and therefore cannot use the same learning strategies. Strategies used for adolescents and adults cannot be used for all students. There is a need for the ELL teachers to understand the skills and cultural heritage of their students’. Fluency and literacy in the mother tongue provides a cognitive and linguistic foundation for learning additional languages when their mother tongue is the primary language of instruction (Ball, 2010).

It has been established that language learning is especially successful when the L2 is used to facilitate understanding well as for the purpose of enhancing reading and listening skills. To achieve this end, ELL educators encourage their students to participate vocally in language classrooms and produce intelligible feedback. Such involvement can help students establish a foundation that will enable them to accurately communicate what they want to say and can be the determining factor in the level of engagement achieved, as was indicated in the responses provided for question three. Furthermore, student participation in verbal interaction offers language learners the opportunity to follow up on new words and structures to which they have been ex-posed during language lessons and to practice them in context, as indicated in the responses for question eight. These factors can provide students with the motivation to learn and improve their conversational skills and behavioral patterns.

Common Literacy Challenges in Multicultural Classrooms

Comprehensive linguistic input is vital to students’ ability to understand oral or written language (Roskos & Christie, 2011). Customizing the lessons according to the students’ age, cognitive levels, and capabilities will ensure that they able to retain the knowledge and assimilate the new language being taught. These three factors, along with continued opportunities for development in their mother tongue, are vital to the successful development of bilingualism in students of diverse linguistic backgrounds (McNaught, 2002). Success in this area also depends on the availability of competent, bi/multilingual instructors that are able to engage the students and provide a multitude of opportunities for development of both languages (McNaught, 2002). The implementation of a multicultural curriculum should be derived from appropriate behaviors facilitated through unprejudiced thoughts and principles. Acceptance of cultural differences are necessitates that prelude the emergence of indicators of good teaching and enables the teacher to create environments that confirm and respect cultural as well as linguistic diversity (York, 2006).

Conclusion

Reflecting the complex and multidimensional nature of anxiety, several recent techniques for anxiety reduction have placed more emphasis on the importance of the student’s self-awareness in dealing with their anxiety, but such techniques as self-talk or imaginary self-dialogue do not always guarantee the actual engagement by the students especially when they are already in anxiety-provoking situations. If employed in conjunction with some personal writing activities, however, their potential utility can be multiplied, because writings accompanied by self-talk exercises seem to naturally foster the students’ own responsibility or initiative to tackle their own language anxiety.

The idea of incorporating writing activities into a collection of anxiety-reduction techniques that already exist as a teacher resource seems to be quite in line with the recommendation offered, which says that the teacher encourage their students to verbalize any fears or nervous feelings that they have experienced in the process of learning and performance in L2 and write them down in a self-reflective journal or diaries. While in some cases, expressing their anxious feelings or inner conflicts in L2 orally may create another psychological burden or further anxiety in some students, writing personal journals or diaries, for example, can provide them with plenty of freedom in terms of time and security, as well as a good opportunity for self-reflection and analysis. Such advantages of writing over those of speaking seem to deserve more attention from both teachers and students alike, especially when they attempt to deal with the issue of anxiety effectively. Limitations to this study present in that the researcher was limited to students in the classes taught. Furthermore, additional studies should be conducted that also analyze how ethnic or multicultural learning differences impact ELL studets.

References

Ajayi, L. (2008a). ESL theory-practice dynamics: The difficulty of integrating sociocultural perspectives into pedagogical practices. Foreign Language Annals, 41(4), 639-659.

Ajayi, L. (2008b). Meaning-Making, Multimodal respresentation, and transformative pedagogy: An exploration of meaning construction insdtructional practices in an ESL high school. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 206-229.

Awan, R.-u.-N., Azher, M., Anwar, M. N., & Naz, A. (2010, November). An investigation of foreign language classroom anxiety and its relationship with students’ achievement. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 7(11), 33-40.

Ball, J. (2010). Educational equity for children from diverse language backgrounds: Mother tongue-based bilingual or multilingual education in the early years. Canada: University of Victoria.

Campbell, K., Combs, C., Kovar, S., Napper-Owen, G., & Worrell, V. (2009). Elementary teachers as movement educators (3rd ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Casteel, C., & Ballantyne, K. (Eds.). (2010). Professional development in action: Improving teaching for English learners. Washington, DC: National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition. Retrieved from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/files/uploads/3/PDF

Chen, C. T., Kyle, D. W., & McIntyre, E. (2008). Helping teachers work effectively with English Language Learners and their families. School Community Journal, 18(1), 7-20.

Chen, I. J., & Chang, C. C. (2009). Cognitive load theory: An empirical study of anxiety and task performance in language learning. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 7(2), 729-746.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Crim, C., Hawkins, J., Thornton, J., Rosof, H., Copley, J., & Thomas, E. (2008). Early childhood educators’ knowledge of early literacy development. Issues in Teacher Education, 17(1), 17-30.

Decker, C., Decker, J., Freeman, N., & Knopf, H. (2009). Planning and administering early childhood programs (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

Eberly, J. L., Joshi, A., Konzal, J., & Galen, H. (2010, Fall). Crossing cultures: Considering ethnotheory in teacher thinking and practices. Multicultural Education, 18(1), 25-32.

Feeney, S., Moravcik, E., Nolte, S., & Chritensen, D. (2010). Who am I in the lives of children? (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

Flick, U. (2011). Introducing research methodology: A beginner’s guide to doing a project. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Foss, K. A., & Reitzel, A. (1988). A Relational Model for Managing Second Language Anxiety. TESOL Quarterly, 22, 437-454.

Gholson, R., & Stumpf, C. (2005). Folklore, literature, ethnography, and second-language acquisition: Teaching culture in the ESL classroom. TESL Canada Journal, 22(2), 75-91.

Giorgis, C., & Glazer, J. (2008). Literature for young children: Supporting emergent literacy, Ages 0-8 (6th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.

Goldenberg, C. (2008, Summer). Teaching English Language Learners: What the research does-and does not-say. American Educator, 8-23, 42-44.

Graziano, A., & Raulin, M. (2009). Research methods: A process of inquiry (7th ed.). Boston, MS: Allyn & Bacon.

Griffiths, C., & Parr, J. M. (2001). Language Learning strategies: Theory and perception. ELT Journal, 53, 247-254.

Helfrich, S. R., & Bosh, A. J. (2011). Teaching English language learners: Strategies for overcoming barriers. Educational Forum, 75(3), 260-270.

Hill, S. (2007). Chapter 5- Multiliteracies: Towards the future. In L. Makin, C. J. Diaz, & C. McLachlan (Eds.), Literacies in childhood: Changing views, challenging practice (2nd ed., pp. 56-70). Sydney: MacLennan & Petty.

Hussein, B. A.-S. (2013, August). Teaching and learning English-as-a-second/foreign language through mother tongue: A field study. Asian Social Science, 9(10), 175-180. doi:10.5539/ass.v9n10p175

Katyal, K. R. (2005). Teacher leadership and its impact on student engagement in schools: Case studies in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: The University of Hong Kong. Retrieved from http://hub.hku.hk/bitstream/10722/41239/6/FullText.pdf?accept=1

King, L. (2013). Experience psychology with connect access card (2nd ed.). Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill.

McNaught, M. (2002). Literacy for all? Young children and special literacy learning needs. In L. Makin, & C. J. Diaz (Eds.), Literacies in early childhood. Challenging views, challenging practice (pp. 233-249). Sydney: Maclennan & Petty.

Morrison, G. (2009). Early childhood education,(11th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

Nassaji, H., & Fotos, S. (2011). Teaching Grammar in Second Language Classrooms: Integrating Form-Focused Instruction in Communicative Context. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis.

Otto, B. (2010). Language development in early childhood (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

Payán, R. M., & Nettles, M. T. (n.d.). Current state of English-Language Learners in the U.S. K-12 student population. Retrieved from http://www.ets.org/Media/Conferences_and_Events/pdf/ELLsympsium/ELL_factsheet.pdf

Roskos, K., & Christie, J. (2011). The Play-Literacy Nexus and the Importance of Evidence-Based Techniques in the Classroom. American Journal Of Play, 4(2), 204-224.

Samson, J. F., & Collins, B. A. (2012). Preparing all teachers to meet the needs of English language learners: Applying research to policy and practice for teacher effectiveness. New York: Center for American Progress.

Tong, J. (2010). Some Observations of Students’ Reticent and Participatory Behavior in Hong Kong English Classrooms. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 7(2), 239-254.

Trang, T. T. (2012, January). A review of Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope’s theory of foreign language anxiety and the challenges to the theory. English Language Teaching, 5(1), 69-75.

Wei, M., Brok, P., & Zhou, Y. (2009). Teacher interpersonal behavior and student achievement in English as a Foreign Language classrooms in China. Learning Environmental Resources, 12, 157–174.

York, S. (2006). Roots and Wings: Affirming Culture in Early Childhood Programs (Revised ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

Young, D. J. (1991). Creating a low-anxiety classroom environment: What does the language anxiety research suggest? Modern Language Journal, 75, 425-439.

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free

guarantee

Privacy

guarantee

Secure

checkout

Money back

guarantee